Introduction

Sexual minority individuals are people whose sexual orientation is not heterosexual, such as lesbian, gay, or bisexual people. Gender minority individuals are people whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth, such as transgender, gender non-binary, and agender people. Sexual and gender minority (SGM, colloquially known as LGBTQIA+) individuals face higher risk for adverse health conditions compared to their cisgender and heterosexual peers, including HIV and STIs, cardiovascular disease, psychological distress, and substance misuse1. SGM health disparities have typically been attributed to sexual and/or gender minority stress and insufficient social safety, including state-level and interpersonal-level discrimination, internalized stigma, and community disconnection2,3.

A large proportion of the LGBTQIA+ population in the US (15–20% or 2.9–3.8 million) reside in rural areas4. Despite their numbers, the rural LGBTQIA+ population is often overlooked in health research and program initiatives. Since 2000, limited psychological research has had an exclusive (1%) or mixed focus (13%) on non-urban LGBTQIA+ participants5. Only 3% of the more than 500 LGBTQIA+ projects funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have focused on rural LGBTQIA+ communities6. LGBTQIA+ programs, especially for youth, are lacking in non-metropolitan areas7. Rural Americans are at higher risk for adverse chronic and behavioral health conditions compared to urban Americans8-10 driven by comorbid risk factors, cultural factors, and less access to primary and specialized health care.

Rural SGM individuals face a uniquely compounded sit of risks, shaped by both rural-specific and SGM-specific factors. Rural SGM individuals reported facing social determinants common in rural areas such as unavailability, high cost, and limited transportation to health and social services11,12. Additionally, rural SGM people often experience SGM-based discrimination from community members and health professionals13-15. As a result of the intersecting effects of rurality and SGM determinants, rural SGM individuals are at a higher risk and experience poorer health outcomes compared to both their urban SGM counterparts and rural heterosexual peers, including higher rates of substance use, psychological distress, cardiovascular disease, and HIV/STIs16-20.

Literature reviews21-25 have highlighted the increasing representation of this intersectional population. However, prior reviews have methodological limitations that limit the knowledge and advancement of rural LGBTQIA+ health. First, most reviews concluded before the year 2021, underscoring the need for a more contemporary synthesis. While Maria et al included articles from 2003 to 2023, they focused solely on mental health care24. Second, most reviews focused on adults. Elliott et al included rural LGBTQIA+ adolescents; however, their work was also limited to mental health-related articles22. Third, and when various health topics are considered, other reviews21,25 have only reported health topic frequencies without addressing population or methodological characteristics of the corpus. Therefore, an updated review covering articles published after 2020, examining multiple study characteristics other than topic (eg population, recruitment methods), and examining differences by study characteristics, are needed to explore and advance contemporary trends in rural LGBTQIA+ health.

We conducted a scoping review to map population, methodological, content, and publishing characteristics of rural LGBTQIA+ health research published since 2000. Identifying trends and gaps in rural LGBTQIA+ health research could guide future research, program, and funding directions for this overlooked yet highly intersectional population.

Methods

Search databases and terms

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (see Supplementary table 1). Medical science librarians (MJF and KH) searched the following databases on 13 December 2024, and uploaded citations into Covidence from the following databases: Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. Our search terms (described in Supplementary table 2) include various terms and MESH terms regarding rurality (eg rural, non-urban), SGM status (eg LGBTQIA+, men who have sex with men), and health (eg health, health care).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our inclusion criteria and review algorithm were as follows: articles were published since 2000, written in English, peer-reviewed, involved primary data, recruited rural SGM populations in the US, dependent variable focused on health, and reported the dependent variable for rural US SGM populations. We excluded secondary data sources (eg national or state surveillance systems, electronic medical/health records) because these sources often lack both sexual orientation/gender identity (SOGI) and rurality measures26,27, are often focused on specific topics and sampling approaches (eg a stratified probability sample of behavioral health with the National Survey on Drug Use and Health), and rurality data tends to not be publicly accessible26. Primary data collection offers researchers more flexibility in study design, content areas, and sampling approaches. We excluded case studies because they are often limited by a sample size of one, often are narrative-based and exclude traditional study characteristics, which create difficulty charting data, and often are used for didactic rather than generalizability purposes28.

Abstract and title screening

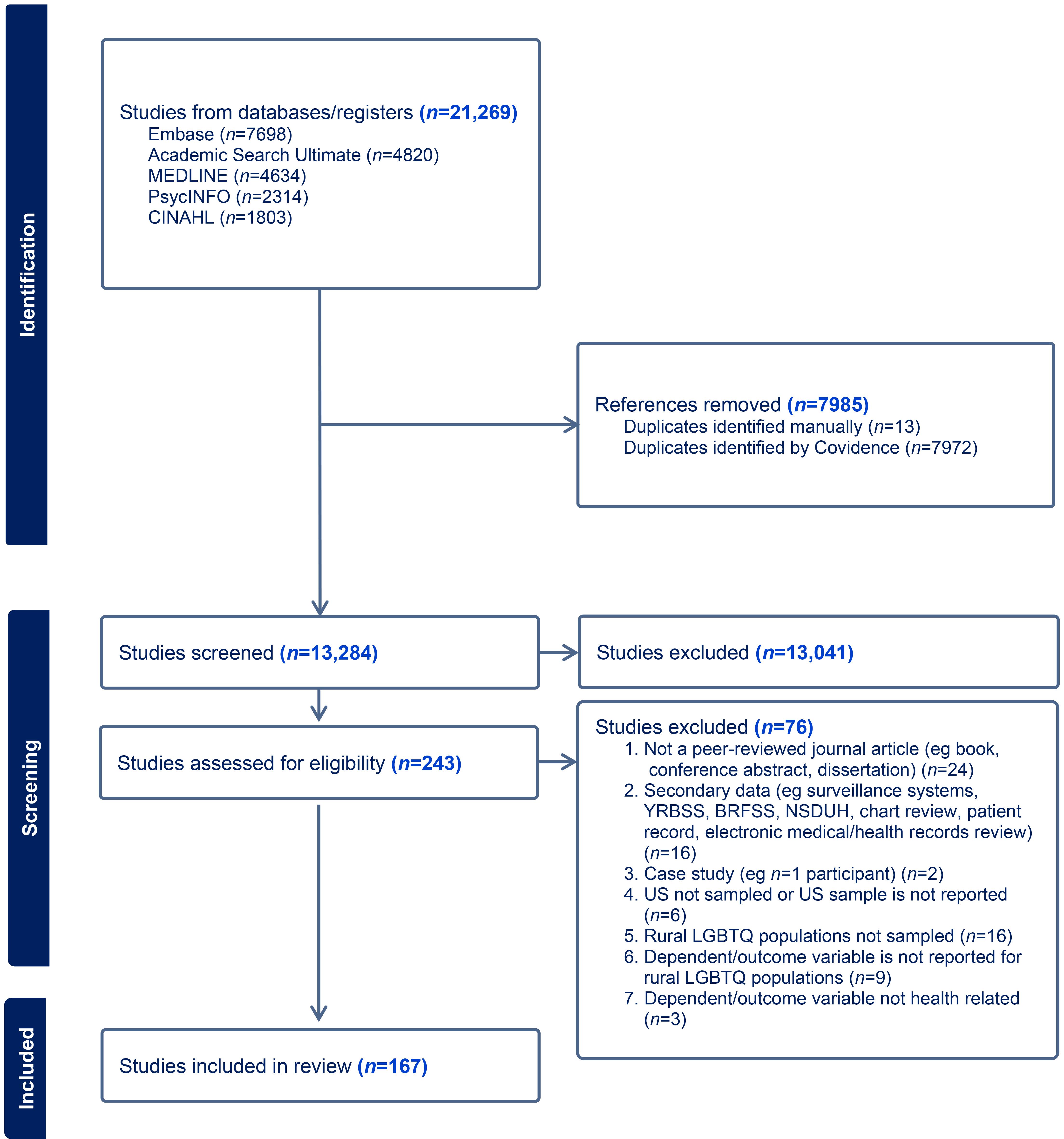

During title and abstract screening, two of the reviewers listed in brackets (VC, RS, KK, CF, VT, JSY, CO) independently evaluated each article, with the principal investigator (CO) resolving any disagreements. To ensure consistency, the principal investigator met with reviewers to discuss project aims and eligibility criteria prior to appraisal. Agreement proportions ranged from 93% to 100% (mean (M)=98.0%, median (Md)=98.9%). Out of 13,284 titles and abstracts that were screened in the first round of review, 13,041 were considered irrelevant, while 243 were considered relevant (Fig1).

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart – identification, screening and included studies. BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. NSDUH, National Survey on Drug Use and Health. YRBSS, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart – identification, screening and included studies. BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. NSDUH, National Survey on Drug Use and Health. YRBSS, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System.

Full-text review

During the full-text review, the group screened 243 articles. To enhance consistency, the principal investigator met with reviewers to restate and give examples of eligibility criteria, and many members from abstract/title screening participated in the full-text screening. Two of the members listed in brackets (RS, KK, VT, CP, MA, CO) independently evaluated each article, with disagreements resolved by the principal investigator. Agreement rates varied from 91.1% to 100% (M=96.2%, Md=96.0%). As seen in Figure 1, 76 articles were excluded, primarily because they were not peer-reviewed articles (n=24), involved secondary data (n=16), or did not sample or report rural LGBTQIA+ populations in the US (n=16).

Data extraction

During data extraction of the 167 articles11,14,15,18,20,29-189, two of the group members listed in brackets (VC, RS, KK, CF, CP, HAO, CO) independently used the data extraction template (see Supplementary table 3). The principal investigator resolved disagreements. To enhance consistency, coders participated in all phases of the data analysis with the principal investigator providing training on the codebook. We extracted data based on sample characteristics (SGM subpopulation group, age groups, geographic setting), methodological characteristics (study type, methodology, recruitment methods, rural measures, compensation), and content characteristics (topical domains of dependent variables). Agreement rates ranged from 66.7% to 100.0% (M=93.1%, Md=100.0%).

After coding, the principal investigator exported data into an Excel file. The principal investigator added the journal, publication year, funder, and compensation amount. See Supplementary table 4 for the evidence table. This Excel file was then uploaded into SPSS v29 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) for descriptive and comparative analyses. Methodological characteristics were compared by methodology type (quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods) and health topics by subpopulation (articles that dealt exclusively with sexual minority men, sexual minority women, transgender and gender-diverse individuals, and multiple populations). Chi-squared tests of independence (χ2) were used for comparisons.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. No institutional review board approval was necessary given the study was a scoping literature review.

Results

Population characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 167 articles. Most of the samples consisted of sexual minority men (83.2%) compared to sexual minority women (42.5%), transgender men (43.1%), transgender women (41.9%), and other gender minority populations (35.9%). About one-third (37.1%) focused exclusively on sexual minority men, 6.0% on sexual minority women, 10.8% on transgender and gender-diverse populations, and 46.1% sampled multiple LGBTQIA+ subpopulations. Most studies targeted adults (82.0%), with 18.0% focusing exclusively on adolescents and young adults. In terms of sampling, 47.9% were state-specific, 36.5% were nationwide, and 15.6% were regional.

Table 1: Population characteristics (N=167)

| Characteristic | Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subpopulation | Sexual minority men | 139 | 83.2 |

| Sexual minority women |

71 |

42.5 | |

| Transgender men |

72 |

43.1 | |

| Transgender women |

70 |

41.9 | |

| Gender minority |

60 |

35.9 | |

| Population category | Sexual minority men (exclusive) | 62 | 37.1 |

| Sexual minority women (exclusive) |

10 |

6.0 | |

| Transgender and gender diverse (exclusive) |

18 |

10.8 | |

| Multiple populations |

77 |

46.1 | |

| Age group | Adolescents (exclusive) | 18 | 10.8 |

| Adolescents and young adults (exclusive) |

3 |

1.8 | |

| Young adults (exclusive) |

9 |

5.4 | |

| Adolescents and adults |

9 |

5.4 | |

| Adults |

122 |

73.1 | |

| Older adults (exclusive) |

6 |

3.6 | |

| Age category | Adolescents and/or young adults | 30 | 18.0 |

| Adults |

137 |

82.0 | |

| Geography | Nationwide or national | 61 | 36.5 |

| Regional |

26 |

15.6 | |

| State |

80 |

47.9 |

Methodological characteristics

Table 2 displays the methodological characteristics of the 167 articles. Approximately two-thirds of articles were quantitative studies (65.3%), 28.7% were qualitative, and 6.0% were mixed methods. Most were formative studies (85.0%), or studies that characterized health outcome/behavior prevalence, examined health determinants, or compared rural–urban or rural LGBTQIA+–heterosexual health outcome/behavior differences. Only 15.0% were intervention studies, or studies that assessed intervention acceptability or intervention effectiveness. While most quantitative and qualitative studies were formative, mixed methods were evenly split between intervention and formative research (χ2=8.26, p=0.016).

The most common recruitment methods investigators used were venue or organizational sampling (60.5%), social and sexual networking advertisements (52.1% and 24.0%, respectively), and snowball or respondent-driven sampling (21.6%). Ten articles (6.0%) did not specify their recruitment methods. On average, investigators employed two recruitment methods (M=1.82, standard deviation (SD)=0.87).

Most investigators self-described the geographic area as non-urban (30.5%). The most commonly used rural–urban standardized measures were the Index of Relative Rurality (15.0%), the Census (12.0%), and the Rural–Urban Commuting Area (6.0%). Some investigators categorized the area by population size or density (10.8%), while others (9.0%) determined rural–urban status based on participants' self-reported responses to a categorical question about community type. Qualitative and mixed-methods studies were more likely to use an investigator description of rurality than quantitative studies (χ2=13.12, p=0.001).

Half (50.3%) offered individual incentives to participants ranging from US$1.50 to US$50 (USD 1.00 = AUD 1.50) per assessment, with an average of US$23.80 (SD=US$11.39). About 11.4% provided raffle compensation, averaging US$44.33 per card (SD=US$11.78). Additionally, 29.3% of articles did not mention incentives, and 9.0% specified that no incentives were offered. Individual compensation was more prevalent in qualitative and mixed-methods studies, while raffle compensation was more typical in quantitative studies. Quantitative studies more often did not offer compensation, while qualitative studies more frequently did not mention compensation at all (χ2=19.68, p=0.003).

Table 2: Methodological characteristics by total and methodology (N=167)

| Characteristic | Variable | n (%) |

Quantitative (n=109) n (%) |

Qualitative (n=48) n (%) |

Mixed methods (n=10) n (%) |

χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study type |

Formative study† |

142 (85.0) | 98 (89.9) | 38 (79.2) | 6 (60.0) | 8.26* |

| Intervention study† |

25 (15.0) |

11 (10.1) | 10 (20.8) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| Recruitment method(s) |

Venue/organizational sampling |

101 (60.5) | 61 (56.0) | 34 (70.8) | 6 (60.0) | 3.08 |

| Social networking or social media app |

87 (52.1) |

59 (54.1) | 21 (43.8) | 7 (70.0) | 2.81 | |

| Sexual networking or hook-up/dating app |

40 (24.0) |

28 (25.7) | 11 (22.9) | 1 (10.0) | 1.28 | |

| Snowball or respondent-driven sampling |

36 (21.6) |

22 (20.2) | 12 (25.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.47 | |

| Participant registry |

14 (8.4) |

11 (10.1) | 3 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1.61 | |

| Online survey market |

6 (3.6) |

6 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3.31 | |

| Mail or phone public records |

1 (0.6) |

1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.54 | |

| Other |

1 (0.6) |

1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.54 | |

| Not mentioned |

10 (6.0) |

5 (4.6) | 5 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2.69 | |

| Recruitment metrics |

Range |

1–4 | 1–4 | 1–4 | 1–3 | |

| Mean |

1.82 |

1.82 | 1.88 | 1.60 | ||

| Median |

2.00 |

2.00 | 2.00 | 1.50 | ||

| Mode |

1.00 |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Rural measure |

Self-described by investigators† |

51 (30.5) | 23 (21.1) | 23 (47.9) | 5 (50.0) | 13.12** |

| Index of Relative Rurality |

25 (15.0) |

14 (12.8) | 10 (20.8) | 1 (10.0) | 1.88 | |

| Census |

20 (12.0) |

16 (14.7) | 3 (6.3) | 1 (10.0) | 2.29 | |

| Population size or population density |

18 (10.8) |

14 (12.8) | 4 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1.2 | |

| Self-reported by participants |

15 (9.0) |

13 (11.9) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (10.0) | 3.96 | |

| Rural–Urban Commuting Area |

10 (6.0) |

10 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5.66 | |

| National Center for Health Statistics |

7 (4.2) |

7 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3.89 | |

| Federal Office of Rural Health Policy or Health Resources and Services Administration |

6 (3.6) |

4 (3.7) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 1.5 | |

| Department of Agriculture |

3 (1.8) |

1 (0.9) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2.19 | |

| Rural–Urban Continuum Code |

2 (1.2) |

2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.08 | |

| Other |

10 (6.0) |

5 (4.6) | 4 (8.3) | 1 (10.0) | 1.14 | |

| Compensation |

Individual incentive† |

84 (50.3) | 47 (43.1) | 29 (60.4) | 8 (80.0) | 19.68** |

| Raffle† |

19 (11.4) |

17 (15.6) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (10.0) | ||

| Not offered† |

15 (9.0) |

15 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Not mentioned† |

49 (29.3) |

30 (27.5) | 18 (37.5) | 1 (10.0) | ||

| Individual compensation metrics (US$)¶ |

Range |

$1.50–50.00 | $1.50–$50.00 | $20.00–50.00 | $5.00–30.00 | |

| Mean |

$23.80 |

$19.92 | $31.54 | $20.00 | ||

| Median |

$25.00 |

$20.00 | $30.00 | $25.00 | ||

| Mode |

$25.00 |

$20.00 | $25.00 | $25.00 | ||

| Raffle compensation metrics (US$)¶ |

Range |

$20.00–50.00 | $20.00–50.00 | $50.00 | $50.00 | |

| Mean |

$44.33 |

$42.92 | $50.00 | $50.00 | ||

| Median |

$50.00 |

$50.00 | $50.00 | $50.00 | ||

| Mode |

$50.00 |

$50.00 | $50.00 | $50.00 |

† Statistically significant differences for quantitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies at p<0.05.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

¶ USD 1.00 = AUD 1.50.

Content characteristics

Of the 167 reviewed articles, the most common topic was sexual health (44.9%), such as condom use self-efficacy, testing for HIV, and pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake. The second most common was mental health (24.0%), such as depression symptomology, psychological distress levels, and mental healthcare utilization. Substance use and substance-use disorders, along with generic health and health care, each constituted 18.0%. Examples of substance-use-related topics include hazardous drinking, smoking and tobacco use, and drug use during sex. Generic health and healthcare examples include quality of life, healthcare service satisfaction, and access to gender-affirming care. See Table 3 for a complete list of topics.

Table 3 also compares content by the subpopulation sampled. Articles that exclusively sampled sexual minority men primarily focused on sexual health outcomes (χ2=39.27, p<0.001). In contrast, articles exclusively involving sexual minority women more frequently investigated metabolic health (χ2=19.40, p<0.001), reproductive health (χ2=15.80, p<0.001), and substance use (χ2=11.51, p=0.009). Studies exclusively involving transgender and gender-diverse people involved mental and generic health topics (χ2=15.21, p=0.002; χ2=20.49, p<0.001; respectively). Broad LGBTQIA+ health articles focused more on substance use and violence (χ2=11.51, p=0.009; χ2=8.58, p=0.035; respectively).

Table 3: Article content characteristics by total and subpopulation (N=147)

| Topic |

Total (N=167) n (%) |

LGBTQIA+ subpopulation(s) studied | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sexual minority men only |

Sexual minority women only (n=10) n (%) |

Transgender and gender-diverse people only (n=18) n (%) |

Multiple populations (n=77) n (%) |

χ2 | ||

| Cancer | 6 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (5.6) | 4 (5.2) | 4.27 |

| Infectious or communicable disease | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 0.44 |

| Mental health† | 40 (24.0) | 6 (9.7) | 2 (20.0) | 9 (50.0) | 23 (29.9) | 15.21** |

| Metabolic health† | 7 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (3.9) | 19.40*** |

| Neurodegenerative or aging | 5 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.2) | 5.44 |

| Reproductive health† | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15.80** |

| Sexual health† | 75 (44.9) | 47 (75.8) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (16.7) | 23 (29.9) | 39.27*** |

| Substance use and substance-use disorders† | 30 (18.0) | 5 (8.1) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (5.6) | 21 (27.3) | 11.51** |

| Social health | 11 (6.6) | 5 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (7.8) | 2.38 |

| Suicide | 7 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.1) | 5 (6.5) | 6.31 |

| Violence† | 18 (10.8) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (5.6) | 14 (18.2) | 8.58* |

| Healthcare discrimination and disclosure | 21 (12.6) | 6 (9.7) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (22.2) | 9 (11.7) | 2.6 |

| Generic health and health care† | 30 (18.0) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (10.0) | 8 (44.4) | 19 (24.7) | 20.49*** |

| Driving safety | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1.18 |

† Statistically significant differences for all LGBTQIA+ subpopulations studied at p<0.05.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Publishing characteristics

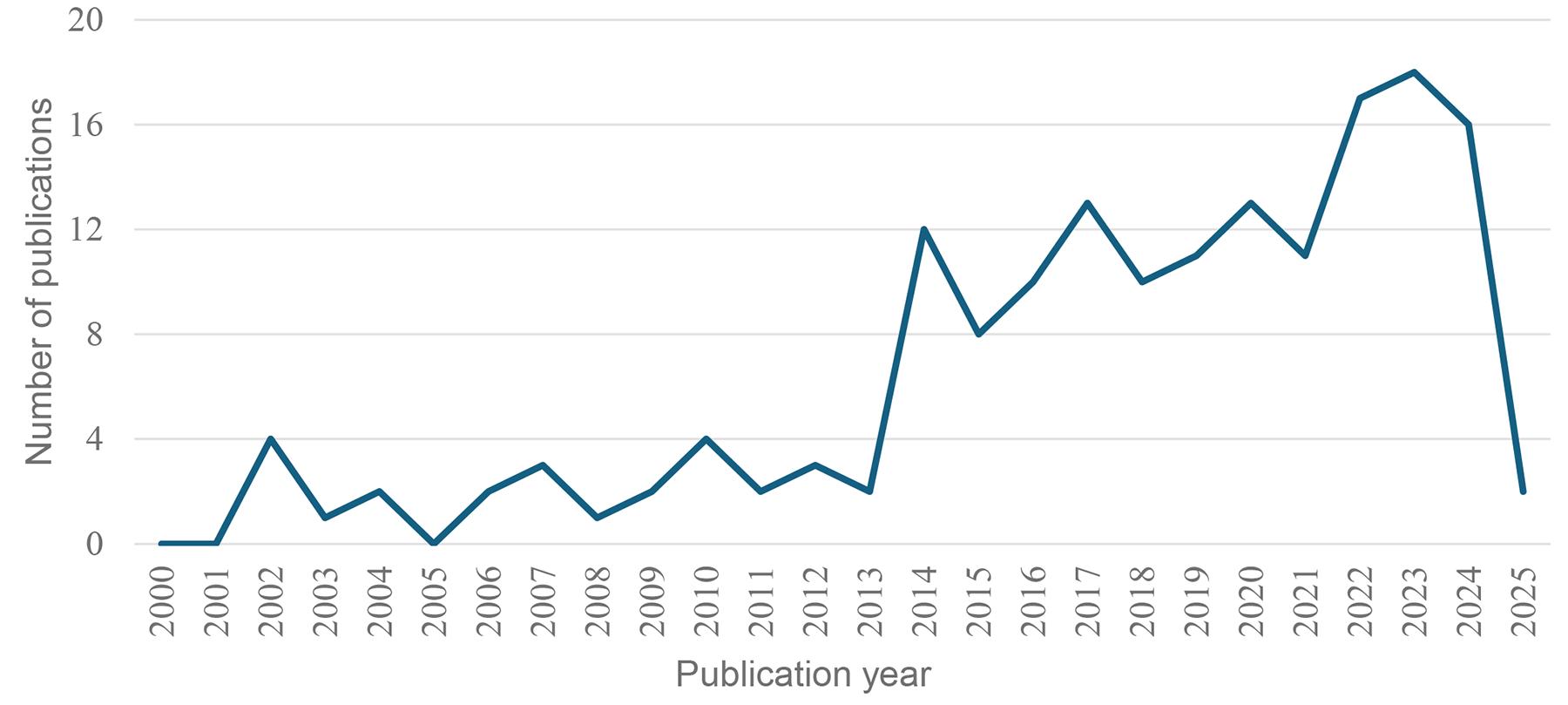

As shown in Figure 2, in the early 2000s the number of rural LGBTQIA+ health publications averaged three articles annually. After 2013, this number grew to an average of 12 articles per year, with 76.1% (n=127) of articles published after 2014. The most published journals were the Journal of Homosexuality (n=11), AIDS and Behavior (n=10), LGBT Health (n=10), AIDS Care (n=7), and AIDS Education and Prevention (n=7) (see Table 4). Over half of the articles were published in LGBTQIA+ health and studies journals (n=42, 25.1%), HIV/AIDS and other STI journals (n=35, 21.0%), or rural health journals (n=12, 7.2%). Approximately 40% of the 167 articles received funding from the NIH, followed by universities (18.6%), organizations or foundations (17.4%), state departments (9.0%), and other federal agencies (6.0%).

Table 4: Publishing characteristics (N=167)

| Characteristic | Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Journal (top 10) | Journal of Homosexuality | 11 | 6.6 |

| AIDS and Behavior | 10 | 6.0 | |

| LGBT Health | 10 | 6.0 | |

| AIDS Care | 7 | 4.2 | |

| AIDS Education and Prevention | 7 | 4.2 | |

| Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services | 6 | 3.6 | |

| Journal of Rural Health | 6 | 3.6 | |

| Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health | 5 | 3.0 | |

| Archives of Sexual Behavior | 4 | 2.4 | |

| Transgender Health | 4 | 2.4 | |

| Discipline of journals | LGBTQIA+ health and studies | 42 | 25.1 |

| HIV/AIDS and other STIs | 35 | 21.0 | |

| Rural health | 12 | 7.2 | |

| Public health and health disparities | 11 | 6.6 | |

| Sexual health and sexuality | 11 | 6.6 | |

| Mental health, behavioral health, and clinical psychology | 8 | 4.8 | |

| Health education, behavior, and promotion | 7 | 4.2 | |

| Psychology, sociology, and social work | 7 | 4.2 | |

| Medicine | 6 | 3.6 | |

| Mobile health, e-health, and telehealth | 6 | 3.6 | |

| Adolescent and youth health | 5 | 3.0 | |

| Alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs/substances | 5 | 3.0 | |

| Aging | 3 | 1.8 | |

| Violence | 2 | 1.2 | |

| Other | 7 | 4.2 | |

| Funder | National Institutes of Health | 66 | 39.5 |

| University | 31 | 18.6 | |

| Organization or foundation | 29 | 17.4 | |

| State or county department | 15 | 9.0 | |

| Another federal agency | 10 | 6.0 | |

| No funder | 40 | 24.0 |

Figure 2: Publication timeline (N=167).

Figure 2: Publication timeline (N=167).

Discussion

Previous literature reviews21-25 of rural LGBTQIA+ health were constrained by methodological limitations, including restricted timelines, narrow topical or population scopes (eg mental health, adolescents), and an emphasis on content frequency reporting rather than other study characteristics necessary to understand and advance the rural LGBTQIA+ health field. To address gaps in prior reviews, we conducted a scoping review to map population, methodological, content, and publishing characteristics to gain a more comprehensive understanding of rural LGBTQIA+ primary health research and to recommend future directions in research, funding, and programmatic efforts.

Population discussion and implications

Approximately one-third of the reviewed articles exclusively sampled sexual minority men. This overrepresentation of sexual minority men aligns with previous literature5,21,190,191 and NIH records192,193. The overrepresentation of sexual minority men in rural research might stem from multiple factors. First, and with publication and reproducibility bias, rural LGBTQIA+ health research might recruit similar populations and methods used in urban or national research to find concordances and discordances, with prior studies mostly sampling sexual minority men5,190,191. Second, current recruitment pipelines and infrastructure are heavily oriented towards sexual minority men. Many online platforms (eg sexual networking apps) and physical platforms (eg LGBTQIA+ organizations) disproportionally serve this population, with fewer online or non-urban organizations tailored to sexual minority women and gender minorities194,195. To address this gender bias, it is essential that funders and investigators include rural sexual minority women and rural gender minorities.

We found that most rural LGBTQIA+ health studies sampled adults, with few sampling adolescents. Most LGBTQIA+ health research and grant funding in the US has targeted adults5,6,193, possibly because of the ethical considerations and additional protections required when involving adolescents in research. Only one rural LGBTQIA+ adolescent systematic literature review exists22. Recruiting rural LGBTQIA+ youth is crucial to develop a life span and developmental approach to rural LGBTQIA+ health research, practice, and policies. Researchers should consult with their institutional review board about best practices in adolescent, LGBTQIA+ adolescent, and marginalized adolescent research conduct and protocols such as parental waivers, developmentally appropriate measures, and youth-friendly recruitment methods196.

We encourage scientists to incorporate SOGI and rurality measures into their surveys. While many faculty acknowledge the importance of measuring SOGI in general research, there is less consensus regarding the relevance of including SOGI measures in their own studies197. Best practices in collecting SOGI data are available198,199, and we recommend scientists consult these resources and share their use among colleagues. In contrast, there is a wider variability in measuring rurality. Researchers may use different rural–urban classification systems, participant-centric or self-reported categorical questions, or their own definitions. There is no standard definition of rurality200, and each classification system has its own advantages and disadvantages200. We encourage scientists to choose the standardized rural–urban scale that best fits their research or projects.

Methodological discussion and implications

Consistent with the broader LGBTQIA+ health research193, most rural LGBTQIA+ health research is formative rather than interventional. This might reflect the development stage of the field. Emerging fields have prioritized formative research to build a foundational understanding of the health needs, facilitators, and barriers that are needed to design culturally, contextually, and tailored health interventions201. As a result, the evidence base for effective interventions remains underdeveloped. Therefore, scientists should design effectiveness–implementation hybrid designs202 to simultaneously assess the clinical outcomes and implementation outcomes (eg acceptability, uptake, cost-effectiveness) of interventions, including the implementation strategies needed to reach the observed implementation outcomes. Moreover, intervention, clinical trial, and implementation studies are generally more feasible, favorable, and frequently conducted in urban areas because population densities, recruitment networks, community and clinical partnerships, transportation options, and other resources are often underdeveloped in rural areas203,204, especially regarding recruitment and clinical and community partnerships that are tailored to rural LGBTQIA+ communities. Because of these infrastructure contexts, program planners may develop online health programs for non-urban LGBTQIA+ communities.

We found that venue/organization-based, social media-based, and chain-referral sampling are common recruitment methods in rural LGBTQIA+ health research. Non-probability sampling approaches are frequently used for hard-to-reach populations including rural LGBTQIA+ individuals205. Venue/organizational-based sampling might be the most common recruitment strategy used because of its direct interaction with rural LGBTQIA+ people and the prevalence of community–academic partnerships or community-based participatory research within the rural LGBTQIA+ health field11,41,52,53,69,84,98,149,150,156,162,166,170. Additionally, many rural sexual minority men prefer health research and programmatic outreach via referrals from organizations and advertisements posted online and in physical venues206.

Content discussion and implications

Most rural LGBTQIA+ health research has primarily focused on HIV-related outcomes. It has been well documented that HIV/AIDS dominates LGBTQIA+ research nationally and globally, including rural LGBTQIA+ studies21,25. HIV/AIDS has a historical legacy of funding, with over half of the NIH LGBTQIA+ portfolio focused on HIV/AIDS6,193. Additionally, HIV/AIDS has a distinctive structural infrastructure across the US, such as through the NIH Office of AIDS Research and Centers for AIDS Research, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US initiative, and the Health Resources and Services Administration’s HIV/AIDS Bureau and the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program207. Due to the historical and ongoing epidemic, governments and non-governmental organizations fund sexual health community-based organizations, HIV service organizations, and AIDS service organizations, and these organizations are often places for community–academic partnerships and recruitment for HIV formative and interventional studies. Moreover, HIV/AIDS research is heavily published given the historic and current HIV/AIDS epidemic, with over half of domestic191 and international190 LGBTQIA+ health literature focusing on HIV/AIDS. This funding, structural, and publication and scientific infrastructure may have established surveillance, methodological, and political accessibility of the topic.

While HIV/AIDS studies have yielded critical insights into HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment, including sexual health disease prevention and health promotion, the predominance of sexual health research has overshadowed other health areas such as mental health, substance use, and chronic disease6,190,191,193. When non-sexual health topics are studied, they are typically conceptualized as syndemic research208, with HIV being the singular or multiple dependent variables. Consequently, the current rural LGBTQIA+ health literature provides an incomplete picture of rural LGBTQIA+ wellbeing and underscores the need for more singular or intersectional research agendas that extend beyond sexual health outcomes. Future research may prioritize mental health, substance use, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, and dementia given these outcomes are the leading causes of death in rural areas in the US209.

Publication discussion and implications

The marked increase in rural LGBTQIA+ health publications beginning in 2014 might be explained by cultural changes. National polls in the early and mid-2000s indicated a growing acceptance of LGBTQIA+ individuals, even among rural Americans210,211. This acceptance may have advanced LGBTQIA+ legal rights and policies such as via Lawrence v. Texas in 2003, the Don't Ask, Don't Tell repeal in 2008, and Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, including the inclusion of SOGI measures in national health surveys. Additionally, broadband access and online recruitment methods made rural LGBTQIA+ populations more reachable. Moreover, the landmark Institute of Medicine’s report on LGBTQIA+ health1 and the Movement Advancement Project’s report on rural LGBTQIA+ health4 were published in 2011 and 2019, respectively. Collectively, these cultural, legal, data infrastructure, and research priority shifts could have created a supportive environment for rural LGBTQIA+ health scholarship.

Over half of the reviewed articles were funded by a federal, state, or county agency. Unfortunately, state governments are increasingly passing anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation212, while the NIH has terminated over 300 active LGBTQIA+ health research awards213. These actions raise concerns about the impact on funding rural LGBTQIA+ health research and programming. Given the recent changes to legislation and funding, further research is needed to examine how these state laws and grant terminations impact the rural LGBTQIA+ health scholarship, funding, and scholarly publication. If the federal and state governments will not fund LGBTQIA+ health research and interventions, it is critical that non-governmental, academic, and other organizations fund such efforts.

As mentioned earlier, it is not surprising that journals focused on HIV/AIDS and other STIs are heavily represented. First, we urge scientists to explore LGBTQIA+-related topics beyond HIV/AIDS and STIs, and encourage all scientists to collect SOGI and rurality measures. Second, we encourage journal editorial boards to consider organizing a special issue focused on rural LGBTQIA+ health, LGBTQIA+ health, or rural health. The only rural LGBTQIA+ special issue we found was by the Journal of Homosexuality in 2014. Senior scientists or established researchers in rural LGBTQIA+ health can advocate for and justify the need for such special issues.

Limitations

This review has limitations, as it focuses exclusively on peer-reviewed primary data articles related to rural LGBTQIA+ health in the US published between 2000 and 2024. As such, it is not comprehensive. Future reviews could include both primary and secondary data to understand rural LGBTQIA+ literature comprehensively. Additionally, future reviews could include international perspectives by including non-English articles or samples outside of Australia, Canada, the UK, or the US While secondary data articles exist16,17, future utilization of national and state surveillance systems is uncertain due to the political factors affecting what measures are included in such systems. Our review focused specifically on rural LGBTQIA+ populations in the US, rather than on the practices and attitudes of rural health providers214-217. However, it is beneficial to understand the implementation determinants and strategies that impact rural providers and professionals implementing LGBTQIA+ cultural competency into their practice or providing evidence-based practices to LGBTQIA+ patients. We did not collect additional data (eg race/ethnicity, independent/predictor variables, bias, quality assessments) due to our research questions and article heterogeneity.

Conclusion

In this scoping review, we examined the trends and gaps in rural LGBTQIA+ health research in the US from 2000 to 2024. We found that sexual minority men and HIV-related outcomes are overrepresented in the literature, while populations like sexual minority women, transgender individuals, older adults, and adolescents are underexamined. Despite the growth in scholarly research publications after 2013, intervention studies are limited. To enhance equity and advancement in this field, future research should investigate a broader diversity of populations, expand the focus of their research beyond HIV-related topics, and adopt hybrid effectiveness–implementation designs so that interventions are effective and acceptable for rural LGBTQIA+ communities, as well as sustainable in rural contexts.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Availability of data

The data and code are available from the corresponding author, CO, upon reasonable request and institutional review board approval.