Introduction

Preventive health care is a key component of a sustainable model of health care1,2. Preventive components of healthcare directives aid in reducing the incidence of chronic health conditions amongst populations3,4. Self-care refers to engagement with behaviours that promote health and wellness5, and may be a critical factor in preventing the onset of chronic disease6. Evidence suggests that engagement with self-care may increase an individual’s ability to preserve and manage their health5,6. It is anticipated that increasing engagement will also lead to improvements in an individual’s quality of life and wellbeing7.

Promotion of self-care is a key global public health priority, and there is a recognised need to promote engagement within remote communities who are geographically isolated8. For example, the findings of a systematic review by Brundisini et al., on access to healthcare in remotely located communities, highlight that geographical location and widespread scarcities of health services may impede on accessibility9. Thereby, it is imperative that remote inhabitants are self-reliant and are active participants in the management of chronic health conditions8,9.

The offshore workforce is a pertinent example of a population who live in a remote and hostile environment10. In the UK Continental Shelf, around 64 000 individuals are employed offshore, of which around 29 000 spend over 100 nights per year in an offshore location10. The nature of shift work offshore, in conjunction with the hazards often inherent in offshore environments, may have a significant adverse impact on offshore workers’ health and wellbeing11. It has been suggested that poor health within the workforce may increase absences from work and, also, increase the risk of medical evacuations (medevacs)12. Accordingly, promoting health and wellbeing within the workforce may be a key factor in mitigating early exit from the workforce due to health reasons and also in enhancing financial benefit13.

It is often assumed that, because the offshore workforce are medically screened, personnel experience optimal health14. However, a recent narrative review on offshore workers’ health and wellbeing identified concerns over a number of domains. The findings of that review emphasised a number of limitations particularly in relation to the current evidence-base being outdated and restricted in the coverage of key health domains15.

Consequently, there is a unique opportunity to develop an up-to-date, comprehensive assessment of health, quality of life and mental wellbeing in the offshore workforce. Further, due to the increasing focus on preventive healthcare, particularly in remote communities, an exploration of self-care within the offshore workforce is warranted. This article describes the outcome of an epidemiological survey, the aim of which was to (i) assess offshore workers’ health, self-care, quality of life and mental wellbeing status and (ii) identify associated areas requiring behaviour change.

Methods

Design

An electronic cross-sectional, epidemiological survey was used to determine the health status, quality of life and mental wellbeing, and self-care status of offshore workers. A pilot study (n=9) was initially conducted to assess the feasibility of the proposed recruitment strategy. Power size calculations were performed for a one-way fixed effects, omnibus ANOVA, using a medium effect size (0.25), α=0.05 and power=0.95. The results obtained from using G Power V software v3.1.7 (http://www.gpower.hhu.de/en.html) suggested a sample size of approximately n=324.

Questionnaire development

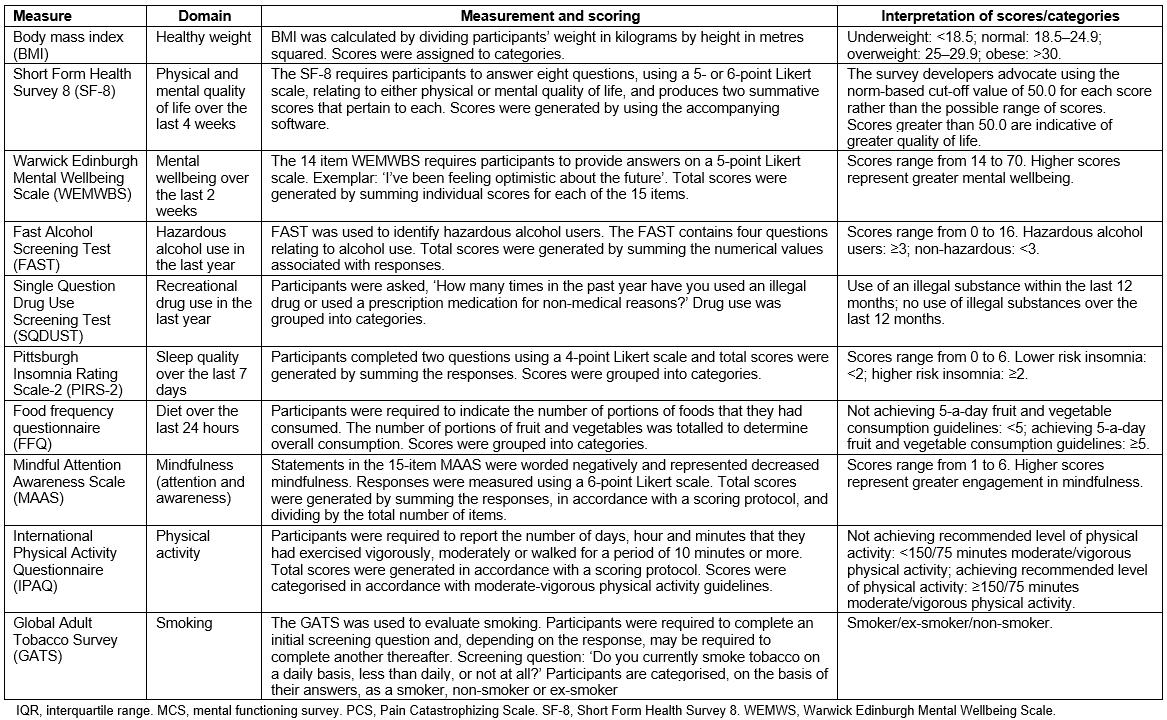

In an effort to ensure face and content validity, the authors invited eight experts in health services research, offshore health and self-care to participate in an expert panel review of the questionnaire. The final version of the survey contained a number of validated tools (outlined in Appendix I) in order to support the assessment, which pertained to either evaluating health status or self-care. Due to the absence of a universal measure of self-care, the seven pillar self-care framework, developed by Webber, et al6, in combination with extant literature on health in offshore workers, provided the basis for the development of a measure tailored to reflect particular features of this specific population.

Health status: Self-reported data on participants’ height and weight were collected and permitted calculation of body mass index (BMI). Participants were asked if they had been diagnosed with a long term health condition, took medication for a long term health condition, and how many medications they took for a long term health condition. Participants were also asked questions relating to work absences and medevacs.

Quality of life and mental wellbeing: Two validated measures were used to determine the health status of the population. The measures assessed participants’ quality of life (Short Form Health Survey 8 (SF-8)) in terms of their physical (Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS)) and mental functioning (MCS survey)16 and mental wellbeing (Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS))17. The rationale for their inclusion was informed by the extant literature18-20 on offshore health, which has emphasised their respective importance. The measures and scoring procedures are outlined in Appendix I.

Self-care domains: Seven validated behavioural measures were used to assess offshore workers’ engagement in self-care (Appendix I). Measures of self-care were selected in accordance with the offshore health literature and Weber, et al’s seven pillar framework, which proposes the following as key domains: health literacy; self-awareness of physical and mental condition; physical activity; healthy eating; risk avoidance or mitigation; good hygiene; and rational and responsible use of products, services, diagnostics and medicines6

The following aspects of self-care were evaluated: alcohol use (Fast Alcohol Screening Test (FAST))21; drug use (Single Question Drug Use Screening Test (SQDUST))22; sleep quality (Pittsburgh Insomnia Rating Scale-2 (PIRS-2))23, fruit and vegetable consumption (food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) element of the 5-a-day community evaluation tool)24; mindfulness (Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)25, physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ))26 and smoking (Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS))27.

Participant recruitment

Offshore workers attending the Further Offshore Emergency Training (FOET) course (n=776) at an operational training facility in Aberdeen, Scotland, were recruited on a daily basis by the researcher, over a period of 16 weeks (October 2014 to March 2015). The FOET operated daily from Monday to Friday with a maximum number of 16 attendees. It is a one day refresher course, which requires successful completion every 4 years to enable offshore workers to maintain their certification to work offshore in the UK Continental Shelf. Only those with prior experience of working in an offshore environment, and who were employed in a position that required overnight stays in an offshore environment, were recruited.

Data collection

Delegates attending the FOET were informed by the trainer that the researcher would be providing a brief of a survey. The researcher orally presented details of the survey in accordance with a standardised script to ensure consistency. Interested delegates were asked to complete a paper contact form with details of their name and email address. Email invitations, including a link to the online questionnaire, were sent out within a 24-hour period. Recipients were asked to complete the questionnaire by the deadline date set for two weeks from the point of contact. All participants were provided with the opportunity to complete the form anonymously to minimise non-response bias28. Each respondent was sent two reminder emails at fortnightly intervals. Participants were provided with the opportunity to be entered into a prize draw for a £50 retail voucher.

Data analysis

The epidemiological data were analysed using the Statistical Analysis Software Package v18 (IBM; http://www-03.ibm.com/software/products/en/spss-statistics). Descriptive statistics were used to report demographics, employment, health status, quality of life and mental wellbeing, and self-care. Means and standard deviations were used where distributions were normal, and medians and interquartile ranges when the distribution was skewed. Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to determine associations between quality of life and mental wellbeing variables and self-care domains. P-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the University School Research Ethics Committee on 17 May 2014. The training site granted approval to access FOET delegates.

Results

Demographics

Of the 776 delegates who attended the FOET course, 657 provided contact details (84.7% response rate), of whom 352 completed the questionnaire (45.4% completion rate). Participants were aged 22–64 years (mean=42.9, standard deviation=10.1), and most were male (n=335, 96.3%) and either married or in a civil partnership (n=258, 74.1%).

Health status

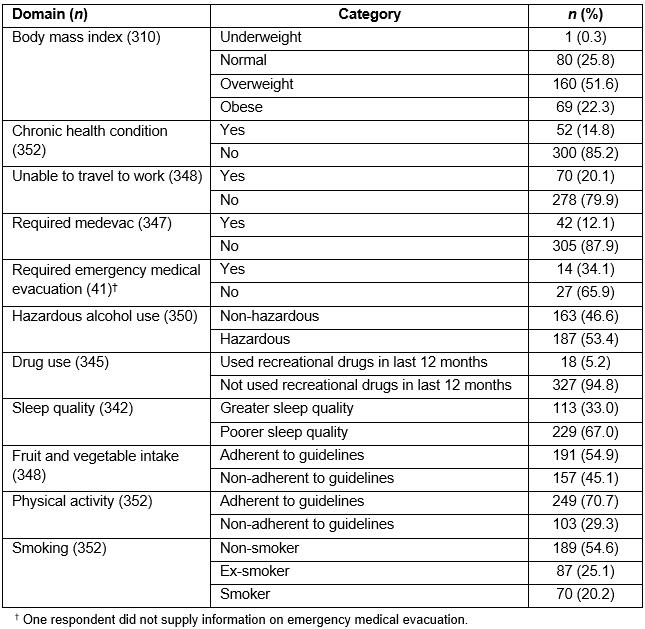

Participants’ BMI values (n=317) ranged from 17.7 to 40.6, with a median value of 27.5 (interquartile range (IQR)=4.9). Almost three-quarters of participants were classified as either ‘overweight’ (n=162, 51.1%) or ‘obese’ (n=74, 23.3%). One respondent was ‘underweight’ (n=1, 0.3%), and the remainder were within a healthy weight range (n=80, 25.2%). Fifty-two (14.8%) participants (n=352) reported that they had been diagnosed with a long term health condition. Of the 50 participants who disclosed having at least one long term condition, 80% (n=40) reported taking medication for their illness(es). The number of medicines taken for each long term health condition ranged from 0 to 5.

Quality of life and mental wellbeing

Median scores for the SF-8 quality of life measure were 56.1 (IQR=4.9) for the PCS (n=338) and 54.7 (IQR=8.1) for the MCS (n=342). Both scores exceeded the norm-based score of 50.0 advocated by the SF-8 developers and were representative of greater physical and mental quality of life. Participants’ mental wellbeing scores (n=326), as determined by the WEMWBS, ranged from 19.0 to 70.0 (out of a possible 14.0 to 70.0) with a median value of 52.0 (IQR=9.0).

Self-care domains

As outlined in Table 1, FAST scores (n=350) indicated that over 50% (n=187, 53.4%) of participants were deemed to be at risk of ‘harmful/hazardous’ alcohol use (score≥3). SQDUST scores (n=345) demonstrated that the majority of the sample did not report using recreational drugs over the previous 12 months (n=327, 94.8%). PIRS-2 scores (n=342) suggested that most participants (n=229, 67.0%) suffered poor sleep quality (score ≥2).

The results from the FFQ (n=348) showed that the majority of participants adhered to 5-a-day fruit and vegetable guidelines (n=191, 54.9%). MAAS scores (n=317) ranged from 1.7 to 6 (possible range 1.0 to 6.0), with a median value of 4.5 (IQR=1.10). Of the 352 participants who completed the IPAQ, around two-thirds (n=249, 70.7%) achieved the 150 minutes/75 minutes of moderate/vigorous activity guidelines. The median value was 56.00 (IQR=9.00). The findings from the GATS (n=352) suggested that the majority were non-smokers (n=195, 55.4%).

Table 1: Health status and self-care of offshore workers

Table 2: Parameters used to categorise self-care of offshore workers

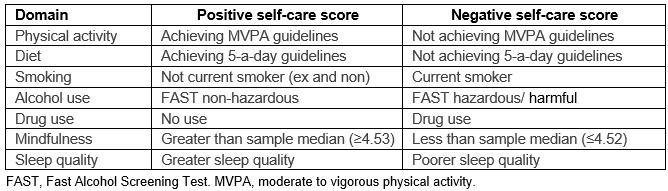

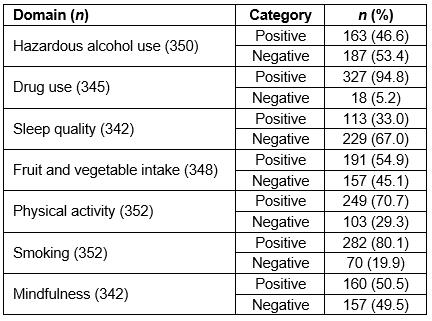

Exploring self-care

Participants’ individual scores across each self-care domain were categorised as either ‘positive’ or ‘negative’. Table 2 describes the parameters used to categorise domains. Positive self-care domains were identified for the majority in respect of fruit and vegetable intake (n=191, 54.9%), drug use (n=327, 94.8%), physical activity (n=249, 70.7%), smoking (n=282, 80.1%) and mindfulness (n=160, 50.5%). Conversely, negative self-care domains identified by the largest proportion of participants pertained to alcohol use (n=187, 53.4%) and sleep quality (n=229, 67.0%) (Table 3). The median number of self-care domains across which offshore workers (n=275) scored negatively was 3 (IQR=2.0).

Table 3: Positive and negative scoring of self-care domains

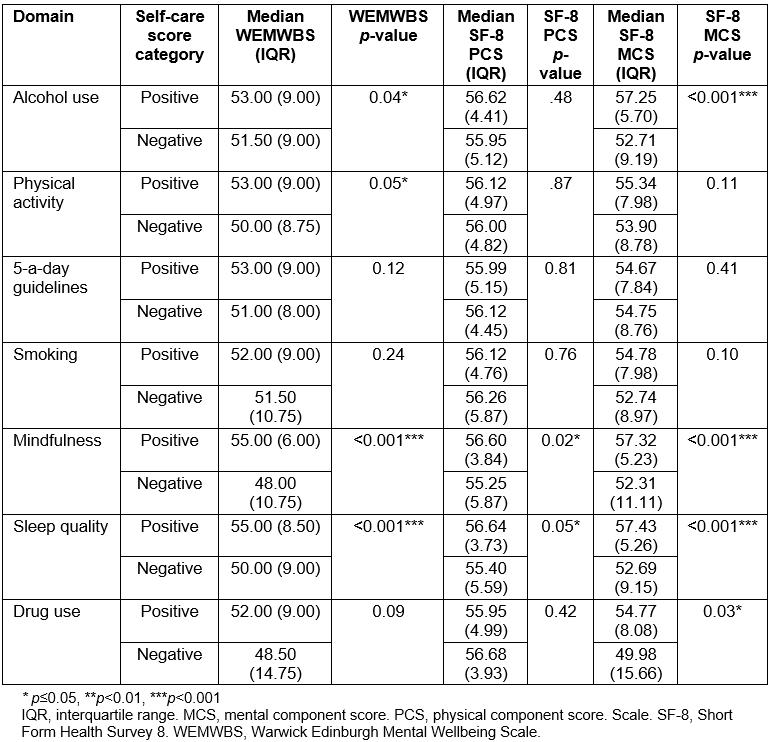

Self-care domains associated with quality of life (PCS and MCS) and mental wellbeing (WEMWBS)

A number of significant associations were observed between self-care domains and quality of life, and mental wellbeing (Table 4).

Those classified as having ‘positive’ scores in respect of mindfulness (U=4558.00, p≤0.001), physical activity (U=9265.50, p=0.05) and sleep quality (U=6768.00, p≤0.001) experienced more positive mental wellbeing (WEMWBS) than those who scored negatively across these domains. Similarly, hazardous alcohol users reported poorer mental wellbeing (WEMWBS) than non-hazardous users (U=11391.00, p=0.04).

In addition, those categorised with positive mindfulness (U=9870.50, p<0.02) and sleep quality (U=10270.00, p=0.05) scores experienced greater physical quality of life (PCS) than those scoring negatively.

Moreover, participants who were classified as having positive scores across mindfulness (U=7515.50, p≤0.001), sleep quality (U=8272.00, p≤0.001) and drug use (U=1747.00, p=0.03) domains experienced greater mental quality of life (MCS) than those who scored negatively. Hazardous alcohol users reported poorer mental quality of life (MCS) than non-hazardous users (U=11026.00, p≤0.001).

Table 4: Mann–Whitney analyses between self-care domains and age, quality of life, and mental wellbeing

Discussion

Main findings of the survey

This cross-sectional, epidemiological survey has furthered understanding of the health, self-care, quality of life and mental wellbeing status of offshore workers by identifying key areas pertaining to health and self-care status that may benefit from behaviour change.

These key areas included overweight/obesity, hazardous/harmful alcohol use and poor sleep quality. Furthermore, most offshore workers’ scored negatively across multiple self-care domains. However, as demonstrated by the distribution of scores, participants were also identified as having positive health across a number of domains including quality of life, mental wellbeing, adherence to 5-a-day fruit and vegetable guidelines, physical activity, smoking, drug use and mindfulness.

A number of significant associations between self-care variables and quality of life and mental wellbeing were observed. For example, poorer mental wellbeing was associated with hazardous alcohol use, poorer sleep quality, decreased physical activity and decreased mindfulness. Similarly, decreased mindfulness and poorer sleep quality were associated with poorer physical quality of life. Moreover, decreased mental quality of life was associated with hazardous alcohol use, drug use, poorer sleep quality and decreased mindfulness.

Key concerns pertaining to offshore workers’ health status were identified, in particular overweight/obesity. The proportion of offshore workers with a BMI in the ‘overweight’ or ‘obese’ categories was similar to those reported in a recent publication29, but higher than historical estimates14,30. This may suggest an increasing prevalence of obesity within the workforce.

Moreover, a number of self-care domains indicated cause for concern within the sample of offshore workers, including the hazardous or harmful use of alcohol and poor quality of sleep. Heavy alcohol consumption has previously been reported within the offshore workforce14,31. Relatedly, shift work disorder, characterised by sleep disturbance, has been reported previously in offshore workers and has been associated with subjective health complaints, pseudo-neurological issues and gastric problems32. For many offshore workers, shift work, involving both day and night shift, is a requisite of employment33, which may pose a challenge in addressing poor sleep quality within the workforce.

The domains identified as positive are perhaps unsurprising due to the nature of offshore work. For example, it may be anticipated that because offshore workers are fitness-screened they would exhibit high levels of psychological and physical wellness. Similarly, the low prevalence of drug use may be expected due to the random drug testing that offshore workers are subjected to.

The results pertaining to physical activity, 5-a-day fruit and vegetable consumption and smoking domains should be interpreted with caution. For example, the findings suggested a comparatively higher level of physical activity than has been previously estimated in the offshore workforce30. However, there were still a large percentage of participants who were not achieving moderate to vigorous physical activity guidelines. Hence, increasing engagement in physical activity may still be a key issue within this remote population. Similarly, the prevalence of smoking was decidedly lower than historical estimates30 and more recent ones29. Whilst smoking was regarded as a positive aspect of self-care in this survey, the majority were categorised as ‘ex/non-smokers’, so any prevalence should be regarded as a risk. Thus, it would be remiss to exclude it is a behaviour that did not warrant attention.

Further, whilst adherence to 5-a-day fruit and vegetable guidelines was regarded as positive within the population, a large proportion of offshore workers did not achieve consumption targets. This reflects findings from the extant literature highlighting the pervasiveness of unhealthy eating habits amongst offshore workers14,30.

The majority of participants scored negatively across a number of self-care domains, which suggests that individuals have multiple aspects that may require behaviour change. It has been acknowledged that engagement in multiple unhealthy behaviours increases the incidence of chronic health conditions and likelihood of premature death34. Furthermore, the likelihood of chronic conditions increases in accordance with age and as evidenced by the findings of this study and the extant literature. Given the age range of offshore workers, a number of personnel may be at increased risk of developing long term health issues10. The management of chronic conditions within the offshore workforce represents a significant global endeavour for both remote healthcare practitioners and offshore workers35. Hence, reducing engagement across multiple domains may be of paramount importance in this remote population.

Strengths and limitations of the survey

This research has addressed the paucity of literature around aspects of health, self-care, quality of life and mental wellbeing amongst the offshore workforce. The recruitment procedures adopted were a key strength of the survey: the researcher was granted access to a training facility that had a large daily footfall of offshore workers who represented a broad demography in terms of age and occupational status. Whilst there may have been a bias in response between those who participated and those who did not, due to the nature of approved recruitment procedures it was not possible to obtain data on the latter. However, the demographic profile of participants was relatively similar to those published in a recent workforce report in terms of age (40.8 years) and gender (3.6% female)10. Further, the power of the analysis was enhanced by the size of the sample, which aligned to previously published literature on health in offshore workers29. Moreover, the sample size (n=352) exceeded the sample size results obtained from G Power V software (n=324) and, hence, would be considered appropriate in terms of the data analysis conducted. The oversampling was conducted in an effort to overcome non-participation associated with completion of online surveys. For example, meta-analyses of response rates to online surveys estimate a rate of between 34% and 39.6% 36,37. Self-report data collected in this survey may have been vulnerable to recall, reporting and response style bias28. In an effort to minimise potential for such bias, the survey utilised a range of standardised measures previously demonstrated to have validity and reliability in evaluating the key concepts.

Implications for remote health

Despite investment in health promotion and surveillance in the oil and gas industry14, the key findings from the survey highlight the predominantly poor health status of those working in remote offshore locations across multiple domains. Although specific causal mechanisms cannot be determined by virtue of the cross-sectional design of this epidemiological survey, these key findings would intuitively suggest that improvement may be attained by the implementation of a self-care intervention – in particular, one that encompasses multiple behaviours, has a strong theoretical underpinning38 and utilises a range of techniques known to facilitate behaviour change39. Encouraging offshore workers to take ownership of their own health may have a positive impact on their overall health status and reduce the likelihood of medevacs. Whilst the findings of this study are specific to the offshore workforce, they highlight the importance of promoting self-care in other remote and rural occupational populations whose access to health care is also limited.

Conclusion

Maintaining and improving the health of employees working in offshore environments may be a crucial component in maximising economic opportunity, ensuring the longevity of the workforce and reducing the occurrence of critical medical incidents. The findings from this research demonstrate that the offshore workforce may benefit from implementation of a self-care intervention that targets multiple behaviours. It is advised that intervention development is underpinned by behaviour change theory to ensure effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

Thanks is owed to the following organisations and individuals for their invaluable contribution to the survey: Institute of Health and Wellbeing PhD Studentship, Robert Gordon University; Petrofac Training Services, Aberdeen; Dr Hector Williams, Robert Gordon University; Professor Graham Furnace, Robert Gordon University, Oil and Gas UK; Professor James Ferguson, Robert Gordon University, NHS Grampian; and study participants.