Introduction

Knowledgeable nursing care may increase the choices rural people have about how they live the end stages of life1. One third of the population of Australia live in rural areas where access to health services is limited by distance and lack of resources2. When provision of adequate care is at risk, nursing support for people who have warning that death is approaching can assist planning that contributes to the quality of life experienced3,4.

Palliative and community care policies in Australia are aimed at increasing the capacity of primary healthcare services to promote choice and independence for an ageing population5,6. To manage the growing demand for care, health professionals working in generalist primary care roles require the competence to provide effective palliative care and support for informal caregivers4,5. They often work in teams with specialist health professionals and community services when complex needs are identified in a person’s approach to the end of life (EoL)4,5. In this context EoL refers to the period when people are living with a terminal health condition4. In an environment of growing demand for limited rural health and social services, nursing action is needed to increase care competence and coordinate the sparse rural resources available for EoL choice7.

International evidence indicates positive rural healthcare outcomes are possible despite service limitations8. Care can be enhanced by health professionals who acquire specialised knowledge and cultural understanding from long-term rural relationships9, and the motivation to advocate for palliative care10,11. Nurses working in the home setting can utilise emotional skills to develop therapeutic relationships that assist the challenging work of EoL care12-15. These assets can be used to build upon connected, supportive social networks8. Advocacy may help people plan and achieve goals for the end stages of life in rural situations; however, evidence of how this is practised in home nursing is limited15,16. Study of DN advocacy practice may raise awareness of how choice and wellbeing can be promoted when people are disadvantaged by the social determinants of rural health17. Exploration in this field provides an initial understanding of how successful EoL advocacy is enabled and actioned; however, further study is required to confirm and expand the evidence available to inform practice15.

Difficulty accessing rural nurses working in the home setting for research purposes across the large geographic areas of Australia is increased by a lack of workforce data detail. The varied populations of nurses working in the community, their roles, work settings, education level and titles, have received little national exploration. Generalist homecare nurses are known variously as primary healthcare nurses, community nurses or DNs in different areas of Australia. Unlike remote area nurses, advanced training may not be required to apply for this role. For the purpose of this study the term DN is used to describe these nurses. The most recent national population survey of DNs in 1982 found a total of 208418; a more recent state-based survey found 775 DNs worked in rural areas of Victoria19. However, resources, populations and models of care vary across Australia5, preventing definitive comparisons for the estimation of the current rural generalist home nursing workforce.

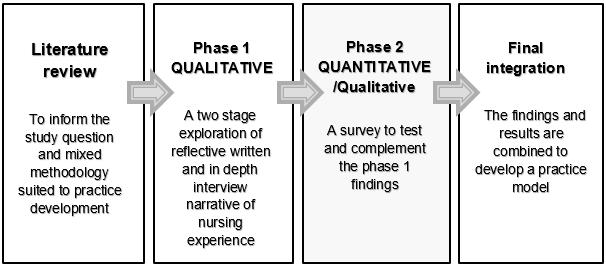

Understanding how DNs advocate for the EoL goals of rural people can inform quality improvements in nursing practice. A practice model developed with validated evidence to increase specific, situated understanding of theory can be used to guide district nursing20. A mixed methods study, commenced in 2014, firstly explored DN reflections on experiences and described how they are enabled and use successful advocacy action to begin the development of a practice model15. This article focuses on phase 2 of the study, which was designed to test and complement the qualitative findings by surveying a larger sample of rural DNs. For the survey, advocacy was defined broadly as action taken on behalf of the health needs and wishes of clients at the individual, community or system level21,22.

The aims of the survey were to test and complement the findings from an in-depth narrative exploration of how DNs advocate successfully for the EoL goals of rural Australians to inform practice23.

Method

Design, setting and population

Pragmatism informed the sequential mixed methods study designed with two phases24 (Fig1). Pragmatism is a ‘philosophical stance that embraces multiple view-points of a research problem’25. A pragmatic approach framed the collection and integration of the mix of qualitative and quantitative data gathered in the exploration of the complex practice question26. In phase 1, DNs from rural Victoria, Australia, were invited to volunteer in a two-stage process of narrative exploration conducted to understand the meanings and process of advocacy in the private world of rural home care23. Qualitative findings from the combination of reflective written experiences and follow-up in-depth interviews provided a beginning understanding of how DNs (N=7) successfully advocate for the EoL goals of rural Australians23. The findings of enabling factors, diverse advocacy actions and the emotional intelligence (EI) required for rural EoL advocacy23 informed phase 2 of study in the construction of the survey of a larger DN sample from across Australia (N=91). Likert scales and open-ended questions were designed to test and complement the findings23 and produce original results.

The instruments available for testing nursing advocacy in the literature focus on protective advocacy27 and attitudes to advocacy28. These instruments were examined and found unsuitable to test the qualitative findings. The phase 1 findings informed the development of two new instruments: advocacy enablers and advocacy action. Open-ended questions were included to explore some findings further and increase the understanding of their meaning in providing evidence for practice.

A Brief Emotional Intelligence Scale (BEIS 10) developed by Davies, et al29 was found to suit the testing of the emotional skills identified in phase 1 descriptions of successful EoL advocacy experience23. EI refers to the recognition, understanding, management and use of one’s own emotions and the emotions of others30. The BEIS 10 is recommended as a reliable, efficient version of earlier EI scales, with comparatively good psychometric properties29. The strategy of an iterative design, combined with trialling the survey and testing the scales using reliability statistics, improved the content validity and internal consistency of the survey31. Results integrated and confirmed in this way can increase practical understanding of successful EoL advocacy26.

The survey was distributed, seeking rural DNs providing EoL care at home. Internet searches and telephone contact were used to identify services and groups that included DNs working in areas classified as inner and outer regions of Australia by the Accessibility Remoteness Index32. DNs working in urban and remote areas were excluded from the study. The response to the survey relied on health services approving and forwarding the survey to individual nurses, who then implied consent by participating. Accordingly, 264 invitation emails were sent out, seeking a purposive self-selecting sample, between March and August 2015. The invitations specified the selection criteria of registered rural generalist nurses with experience of successful advocacy for the goals of people receiving EoL home care. An electronic link to the anonymous survey available online in Qualtrics was included, with a copy attached for prior viewing and postal return if preferred. The lack of an early response from nurses in Queensland instigated further contact with the major care organisation. This resulted in an ethics application that was not approved due to the study timeframe, preventing further survey distribution.

Figure 1: Representation of the sequential mixed methods study designed to highlight positioning and purpose of phase 2 survey.

Figure 1: Representation of the sequential mixed methods study designed to highlight positioning and purpose of phase 2 survey.

The instrument

The survey instrument was a questionnaire that included three sample profile questions, three scales to test a total of 62 items, and eight open-ended questions to gain additional understanding33. The scale responses were rated using five-point Likert scales, with ‘1’ representing the most positive rating and ‘5’ the most negative. In the scales using levels of agreement, ‘3’ represented ‘neither agree nor disagree’. The survey was divided into four sections:

- multiple choice questions to assess the representative nature of the sample profile within the selection criteria

- advocacy enablers rated for the levels of agreement to 27 items describing factors identified as enabling successful DN advocacy. The addition of six open-ended questions triggered by positive item responses was used to gather information about motivation, knowledge and support. One additional question invited suggestions for alternative factors enabling advocacy

- advocacy action rated for the levels of importance given to 25 items for factors identified as actions used in successful EoL advocacy. One open-ended question was included to invite further suggestions of factors

- the BEIS 10 rated by levels of agreement to 10 items to test the EI of nurses who advocate successfully29.

The instrument was trialled by 13 university-employed rural health professionals and included three nurses with experience in primary health care. The questionnaire was completed within a 10–15 minute timeframe, which was considered reasonable for participation34. The trial feedback was used to improve clarity to increase the response quality and reorder the scale items to begin the survey with simple concepts34.

Analysis

The scale results were analysed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences v21 (IBM; http://www.ibm.com/analytics/au/en/technology/spss/) after cleaning the data by checking that the values attributed to responses were represented accurately. Replacement values were not given to the missing data, which were made evident instead by reporting the number of responses per item (detailed in full) in the tables presented (Tables 1–3).

Calculations used percentages for the sample profile, and the scale results were interpreted as interval data in the manner generally accepted for psychometric testing34,35. Mean, standard deviation, percentages and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to examine the descriptive statistics of the scale values rated by the DNs33. The values are reported as percentages to provide clear understanding of the results. Cronbach’s alpha was used to check the reliability of the scales by testing the ability of the items to measure the concept of interest, with values greater than 0.70 indicating acceptable levels34. The Cronbach’s alpha ratings for the scales were calculated as 0.86 for the advocacy enablers, 0.93 for the advocacy action and 0.78 for the BEIS10.

Qualitative data from the open--ended questions were coded in NVivo QRS 10 (QSR International; http://www.qsrinternational.com/) and then analysed using descriptive interpretation to compare findings for fit with those found in phase 1. Some responses were quantified to calculate the level of importance for each response attributed by the sample. Complementary data from the open-ended questions added to the understandings provided by the phase 1 exploration.

Ethics approval

Approval for the survey was granted by the University College Human Ethics Committee (FHEC14/037). Further ethical approvals were sought when required by health services.

Results

The survey was opened in Qualtrics 109 times, commenced by 91 respondents and completed in full by 77 respondents. The rate of missing data increased as the respondents worked their way through the survey.

Sample profile results

Of the total sample responding to the profile questions (N=91), 6.6% were male and 93.4% were female. The majority of the respondents (93.4%) reported at least 2 years of experience in rural home nursing. Successful advocacy was provided by most of the respondents for between two and five people (40.7%), or more than five people (39.6%) in the previous year.

The majority of the completed questionnaires (N=77) were returned from the states of Victoria (N=37) and New South Wales (N=20), which have large inner and outer regional areas. A smaller response was received the states/territories of Western Australia, (N=7), South Australia (N=6), Northern Territory (N=3), Tasmania (N=3) and Australian Commonwealth Territory (N=1). No completed questionnaires were received from Queensland. The origin of the incomplete questionnaires (N=14) was not registered in Qualtrics.

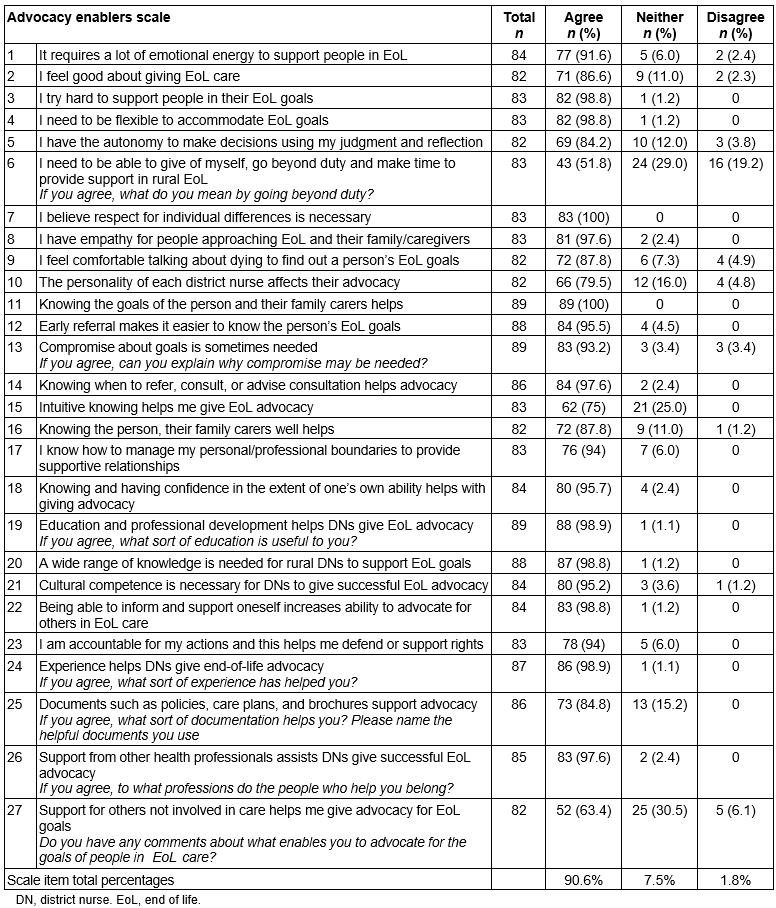

Enablers of successful advocacy

The results in this section confirmed and complemented the phase 1 findings of enabling factors for successful DN EoL advocacy23. Results for the scale items in Table 1 indicated a high level of agreement overall (90.6%). The results are described using both the scale percentages and answers to open-ended questions. The section was commenced by 89 respondents. Responses decreased with progress through the questionnaire, and 82 respondents completed this section (Table 1).

Two scale items received 100% agreement: ‘I believe respect for individual differences is necessary in my role’ and ‘knowing the goals of the person receiving EoL care and their family carers’ helps’. Advocacy enabled by ‘early referrals, self-understanding and confidence’, ‘knowing how to balance relationship boundaries’ and ‘when to refer and consult’ were all rated very highly. Respondents who agreed that ‘compromise of goals is sometimes needed’ (93.2%; n=83) were asked to expand with their knowledge about why this occurs. Responses outlined expectations that were unrealistic due to limited service hours, staff expertise or availability, sudden unmanageable deterioration in health, and insufficient carer support or coping. Some goals reportedly lacked the general practitioner’s support, adequate information for preparation, or were illegal or unsafe for nurse participation. Knowledge of the rural people and the resources available were confirmed as enabling EoL goal modifications that met with satisfaction.

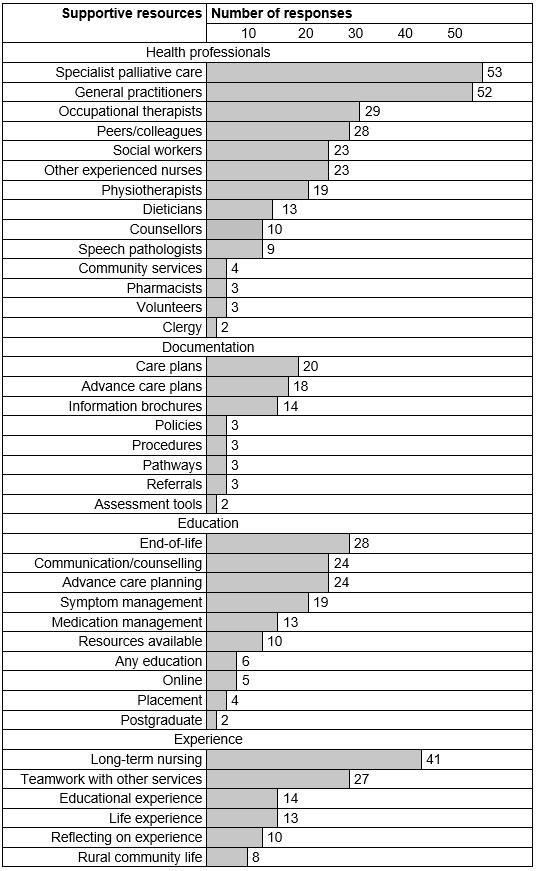

Self-support derived from ‘experience, education, a wide range of knowledge’ and ‘being able to inform and support oneself’ was highly rated (>98.8%). Support from other health professionals was also rated highly (97.6%; n=83), whereas support from people not involved in care received a lower level of agreement (63.4%; n=52). The answers to open-ended questions added explanatory data about experience, education, documentation and health professional support for successful EoL advocacy. Figure 2 presents quantified results of the open-ended question asking about sources of support.

In describing self-support in advocacy, DNs reported long-term nursing experience (n=41), supportive rural health teams and community life, with the use of education and personal reflection to advance care practice. Drawing on this experience was said to help DNs appreciate differences by ‘knowing yourself’ (DN 60) and being able to ‘remain impartial and think laterally’ (DN 56) for advocacy. One DN who identified a lack of experience also responded negatively to scale items focusing on feeling good about EoL care and talking about dying.

The most common support provided by others was identified from palliative specialist doctors and/or nurses (n=53) and general practitioners (n=52). Support from nursing peers and allied health professionals, especially occupational therapists, also featured highly in the responses. The education found to be supportive was most commonly reported as EoL training (n=28), closely followed by communication, symptom management and advance care planning. The most supportive documentation was reported as care plans that provide clear goals (n=20), and advance care plans, followed by simple information to give to people.

The largest variation in agreement in the scale was found in the item ‘I need to give of self, make time and go beyond duty to provide advocacy successfully’, which received 51.8% (n=43) agreement. An open-ended question explored the concept of volunteering effort by asking, ‘What do you mean by going beyond duty?’

Those who responded (n=37) stated it involves spending extra time and effort to help people achieve their EoL goal of staying at home. Effort was reported as volunteering support in response to need that was not covered by the formal role or hours of work but seen as a normal part of smaller rural community expectation, such as informal on-call care, seeing the person’s family and stopping to ‘have a chat in the street’ (DN 72), where ‘everyone knows you, and your number is in the book’ (DN 3) or you give them your ‘personal mobile’ number (DNs 23, 75). One DN enlarged on balancing professional and personal roles in caring for a man who was once a school friend:

Our service supported this man to die in his home with his three teenage children – one of which I employed locally – the effort as a staff and community member was challenging … it was required of me to have very difficult end of life conversations along with explaining the systems … for this man to die at home – these people … had no concept of what was involved … I really had to compartmentalise my role as a professional and friend. (DN 11)

Care beyond duty was described as potentially risky if provided outside service insurance cover; however, the ability to put aside one’s own beliefs, ‘be someone they can relate to’ (DN 85) and give emotional support was considered important; ‘Cry and laugh with clients, not to mention the occasional hug’ (DN 32). Going beyond expectations was identified in actions that may be seen as outside the usual role of DNs, such as sourcing and collecting supplies or equipment and taking on care normally provided by family, friends and social workers when available. EoL care in the rural context was identified as ‘very complex and there are no specific right or wrong pathways to take’ (DN 73), validating the positive scale responses, such as the need for autonomous action to advocate successfully.

The phase 1 findings of advocacy enablers were additionally confirmed by answers to the last question: a request to articulate additional advocacy enablers23. Personalisation of care involvement that increases the ability to know and understand the person, family and their goals was the most frequently reported factor, aided by respect, communication skill and understanding of self. This was expressed as the ‘ability to listen really well … to ‘sit’ outside myself so … planning is family/carer focussed’ (DN 76).

Table 1: Enabling factors of successful advocacy in end-of-life district nursing

Figure 2: Supports for rural district nursing end-of-life advocacy.

Figure 2: Supports for rural district nursing end-of-life advocacy.

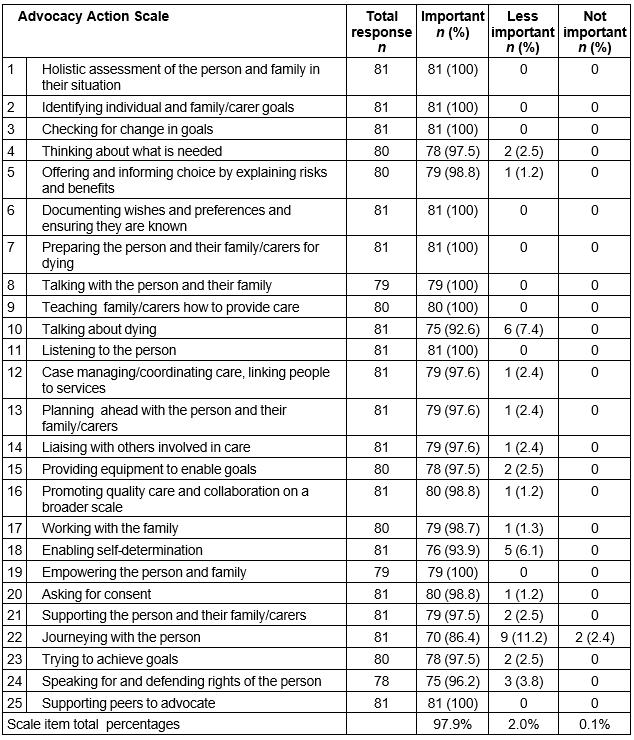

Actions of successful EoL advocacy

The advocacy actions identified by rural DNs as important for EoL advocacy success in phase 1 of the study23 were confirmed by the results of the survey. The rate of missing data varied in this section, resulting in 79–81 responses per item. The types of actions used in advocating for person-centred goals found in phase 123 were used in the scale items that are in Table 2. The actions required for successful advocacy were rated highly on a scale of importance by 97.9% of the respondents overall. Many items were rated as important by 100% of respondents: ‘holistic assessment’, ‘identifying the individual goals of the person and family carers’, ‘checking for change in goals’, ‘effective listening, talking’ and ‘preparing the person and family for dying’; also ‘teaching family how to provide care’, ‘empowering the person and family’ and ‘supporting peers to advocate’. There was little variation in the responses and the only item to receive any negative response (n=2) was ‘journeying with the person’.

In response to the open-ended question requesting additional successful advocacy actions, the need for effective communication and flexible, personal relationships was reiterated. Being able to respond to changing goals in a timely manner, and showing respect for differing values, was confirmed. Respect for the rights and values of others was highlighted in the open-ended responses generally. Several respondents pointed out that their ability to care for and about others comes from being motivated to provide the respectful caring they would want for themselves or their loved ones. A need for broader advocacy that respects individual rights in EoL care and includes bereavement policy and resources was emphasised.

Table 2: Actions of successful district nursing end-of-life advocacy

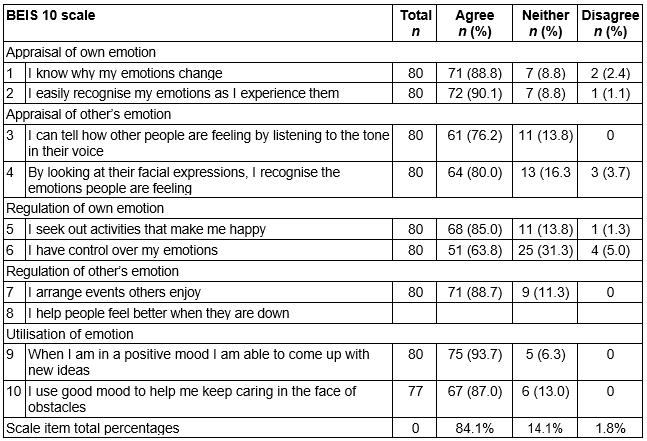

The BEIS 10

The emotional skills described by DNs in their successful advocacy experiences in phase 1 of the study23 reflect the five concepts of EI itemised in Table 3. Eighty respondents rated the items, until the last item, which received 77 responses. The overall agreement received in the BEIS 10 (84.8%) demonstrates the respondents self-rated their EI positively. The items that assessed the use of emotion were rated most highly. None of the respondents disagreed to the utilisation of good mood to ‘come up with new ideas’ and continue ‘caring in the face of obstacles’. Overall there was 1.8% disagreement to the BEIS 10 items. The item assessing the respondent’s ability to control personal emotions received the greatest disagreement (5%; n=4).

Table 3: BEIS 10 scale for successful rural district nurse advocates

Discussion

The sample responding to the survey provided a broad cross-section of the population fitting the selection criteria. The ratio of male to female respondents was slightly underrepresentative of the community nursing population, which includes other roles36. The survey results supported the phase 1 study findings that described how DNs are able to advocate successfully for rural Australian EoL goals23. Responses to the survey confirmed that success requires DNs who are willing to use the autonomy available in their role to involve themselves in person-centred care relationships15. Knowing the rural people and resources together with support from the variety of sources were also confirmed to contribute to enable advocacy success in rural EoL caring15.

These results align with Kohnke’s theory that proposes self-advocacy in the form of gathering information and support can enable advocacy for others22. The motivation of rural DNs found to increase EoL choice resulting from respect for people, beneficial relationships and the satisfaction of good outcomes corresponds with international rural health findings37. Ensuring rural DNs have the support to prepare and sustain themselves in EoL care appears to increase their effort to improve care1. The results indicate this effort involves advocacy action.

Some of the actions driven by advocacy that were confirmed in this survey have been documented in the general community nursing literature38,39. However, evidence of success from advocacy action adds new knowledge of nursing care focused on person-centred goal identification to empower people to manage EoL care in their rural home situation. The results show rural DNs balance their professional and personal involvement in the community for advocacy action that is morally justified by the emotional response to person-centred goals.

The emotional skills identified by DNs possessing the ability and ‘passion’ for advocacy for person-centred EoL goals23 is supported by positive self-rating of EI in the survey. The confirmation of EI used in advocating through flexible and proactive nursing relationships is congruent with previously reported emotional skill needed in effective DN EoL care12. As a learned ability, EI can be nurtured with supportive education, reflection and supervision12. DNs who have developed high levels of EI may be more motivated to provide emotional care and manage the emotional stress reported in the literature13,40 and in the advocacy efforts reported in this study that can sometimes take them beyond duty. The act of going beyond duty to address need in this study is congruent with the care commitment motivated by emotions identified in rural Canadian EoL care10. Going beyond duty in advocating for the goals of rural Australians requires DNs to utilise EI to ensure the response to goals is person centred. A moral response to these goals considers the effect of action taken on all the people involved in care, and includes self-care to minimise emotional overload15.

The results of the survey validate the phase 1 findings about how successful advocacy is enabled for rural DNs who take action as moral agents, reflecting on their practice and the outcomes of advocacy to improve EoL choice in the community23. In addition to confirming the findings, the responses to scale items in phase 2 demonstrated a low variability that increases confidence in the reliability of the results35. The risk of bias and result interpretation error was also reduced by seeking professional advice and review from health researchers experienced in quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods study.

Evaluation of successful rural health service, such as DN EoL advocacy, can inform policy and management, ameliorate rural health disparities and help implement best practice in changing circumstances41. The phase 1 findings integrated with the results of the phase 2 survey increase confidence in the understandings developed about successful person-centred advocacy to inform a DN practice model that supports current Australian policy.

Limitations

Despite confirming the findings of successful advocacy, phase 2 of the study has limitations. Participation may have been affected by the lack of time and the other pressures identified by DNs in phase 1 of the study, and in the literature14,16,40. Time pressure may have impacted on the number of surveys with missing data. Despite this, the incomplete nature of some surveys was assessed as unlikely to influence the effect size33,34. Participation was also affected by difficulty in accessing the target population when services required additional complex national, state and/or organisational ethical approvals that could not be acquired in the study timeframe. This prevented national representation.

The method of data collection may also have influenced results, as self-report on scales is affected by memory and social desirability33. Lack of explanation of the EI concepts could have impacted on interpretation. Accurate self-assessment also relies on psychosocial skill31 and perceptions of personal abilities, which can vary over time and with mood29.

In addition, caution is needed in interpreting the rating of Cronbach’s alpha intended as a test for statistical reliability35. Item and response numbers can affect the result, and systematic error may occur if the items vary in consistency from the constructs being tested42. Further testing is recommended for the psychometric properties of the advocacy enablement and advocacy action scales.

Conclusion

The results of the survey confirm and complement the description of successful advocacy for the EoL goals of rural Australians in this study. The willing and supported use of the autonomy available in the DN role to make time and become involved with people receiving EoL care is needed to advocate for person-centred goal planning. Relational knowledge enables respectful understanding of the people and rural resources available for advocacy. Support from a variety of sources assists self-care to promote confidence in providing choice in emotionally and ethically demanding rural EoL care. Higher levels of EI enable DNs to manage the moral dilemmas and responsibilities of person-centred EoL advocacy.

DNs take advocacy action successfully for the EoL goals of rural Australians using respectful relationships that facilitate access to choice. Advocacy underpins the process of holistic assessment, communication and organisation of empowering, supportive care. This survey highlights factors enabling advocacy action in complex rural EoL relational care that may reduce the need for DNs to go beyond duty to provide effective care. The evidence-based understanding gained in this study can be used with confidence to inform a range of quality improvements and develop a practice model that can assist rural DN EoL advocacy care in line with community and palliative care policy.