Introduction

Thailand is a country of 65 million population, with 55 164 doctors providing a public health system that offers universal access to specialist care without need for referral from primary care, as well as a highly developed urban private hospital system1. Since the 1990s, Thailand has recognised and sought to remedy the rural doctor shortage caused by medical workforce maldistribution and low doctor retention in rural areas. Publicly funded medical students are required to spend 3 years immediately following graduation working in rural areas. These doctors (known as general practitioners or GPs) can choose to study the speciality of family medicine during their 3 years of rural service, or can return to the city after completing this commitment to train as a family physician or other discipline specialist. The Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) has collaborated with the Ministry of Education to recruit rural background medical students and educate them to become rural GPs working in their own rural communities for a minimum of three obligatory years of rural service. This medical education partnership, the Collaborative Project to Increase Production of Rural Doctors (CPIRD), established in 1994, produces approximately one-third of the total publicly funded medical school graduates each year2. This has greatly increased the number of medical students doing preclinical medicine in 14 university medical schools across Thailand and has increased capacity for clinical training outside university hospitals mainly based in 37 accredited MoPH hospitals. All CPIRD and regular track students need to sit the same national exams in order to work clinically in Thailand on graduation. Despite the success of this rural student recruitment strategy, many challenges still exist to overcome persistently low rural doctor retention beyond 3 years3.

Rural community-based medical education (RCBME) can be defined as a mainly clinical placement where medical student learning activities take place within a rural community. Students, clinical teachers, other health professionals, members of the community and representatives of health and government sectors actively contribute to the educational process, with the aim to produce community-oriented doctors who are able and willing to serve their community and deal effectively with health problems at primary and secondary care levels4. Based on the international evidence, it was proposed that a RCBME program could enhance medical students’ interest in rural medicine and assist rural retention following graduation5-7. The argument was that, because educating students in a rural practice context provides learning experience of rural practice and builds students’ relationships with rural clinicians, health service and the community, then they are more likely to remain connected to rural practice and build a life in that community8,9. CPIRD is therefore seeking to develop a series of Thai RCBME programs, with the first program to be located in Songkhla Province in the southern region of Thailand in 2019.

There is a broad range of medical education and health services in Songkhla Province. Prince of Songkla University Hospital is the super-tertiary hospital and medical school location for training undergraduate medical students and postgraduate specialties in the southern Thai region. In addition to the university hospital, health services include tertiary hospitals located in urban areas with a full range of specialists and facilities for caring for patients, and secondary hospitals located in each province with a limited range of specialists and facilities. Most medical education centres (MECs) are located in tertiary hospitals and some MECs are located in secondary hospitals, where specialists are responsible for teaching CPIRD students (as affiliated institutions) and their postgraduate specialised trainees. Finally, there are primary district hospitals in rural or remote areas, with a limited number of general practitioners and facilities, as well as limited onsite access to specialists. Outside the public hospital system there are three private hospitals and some general practice and private specialist clinics in urban Songkhla Province. The private sector does not have any responsibility for medical education. This study examines the development of an RCBME program in a primary district hospital context supported by its associated MoPH tertiary hospital and MEC.

In preparation for this RCBME program, authors sought to understand stakeholders’ views of RCBME programs and through this recognised a dearth of articles reporting prospective stakeholder analysis4. Literature on stakeholders’ retrospective views of existing RCBME placements included that these programs facilitated relationships between students, their clinical teachers, patients and community10. These relationships were seen to influence students’ development of clinical competence and professional identity including as a rural practitioner4,11. This was thought to have potential for cultivating the rural medical workforce12. Although such stakeholder views were mostly positive, a number of challenges were reported that needed to be managed, including the need for students in the less structured RCBME environment to manage their time, balance work and study, and be self-directed learners13-15. The majority of reports on stakeholder views on RCBME came from well-resourced Anglosphere countries and reflect that context4. There is very little published about establishing RCBME in lower resources contexts16. One study found that students trained in a high resourced RCBME context had difficulty applying their practice knowledge in a lower resourced context in the Solomon Islands17.

It is likely that the impact of an RCBME program will be different in a lower resources context, such as rural Thailand, and stakeholders may have different expectations and concerns. Using a case study research design, this research sought to explore stakeholders’ expectations on an RCBME initiative in Songkhla Province, Thailand. Reporting such consultations will build knowledge of RCBME across contexts with a view to understanding the impact of context on implementation of RCBME programs.

Methods

This study utilised a qualitative case study method to explore stakeholder perspectives in Songkhla Province, the location for the first proposed RCBME program18. The case was defined as the province of Songkhla, its health services, the community of patients, the history of medical education, and those involved in either university medical school or MECs. External to the case but relevant to the development of the RCBME is CPIRD, the Thai Medical Consortium and the Thai Medical Council, which studies such as this can inform to optimise implementation of RCBME in Thailand.

The conceptual framework for the case design and analysis was the symbiosis model, which describes RCBME programs as positioning students in the centre of four sets of relationships: clinical, institutional, community and personal19. Participants were purposively chosen to represent the broad range of Thai stakeholders, as defined by the symbiosis model, who would need to be engaged in the RCBME program in Songkhla Province. Within each group of participants, one of the researchers (PS) sought a range of prior experience with rural practice and rural teaching/learning and categorised participants as having little, some or plenty of experience. Individual audiotaped semi-structured interviews explored participants’ perspectives on the concept of an RCBME program. All interviews were transcribed in Thai as the source language. All transcribed data were carefully de-identified in order to ensure participants’ anonymity and confidentiality. Grouping of rural doctor, nurse and community member responses was necessary to preserve anonymity.

The analysis of the data in this study was conducted in three stages. First, four transcripts were translated in English and coded by researchers PS and LW to develop an initial set of codes. Second, all transcribed data were categorised in Thai language (by PS) according to four axes of the symbiosis model, building on this initial set of codes19. Third, multiple quotes used to develop codes within each symbiosis category were translated from Thai to English (by PS) and then analysed within each symbiosis axis. Translation was deliberately literal to keep the English words as close to the Thai words actually used, and this is reflected in the quotes provided. This often triggered discussion about meaning between the Thai and English speaking researchers. At this stage the analysis was refined through discussing and reflecting upon the English meaning of quotes relative to the original Thai transcripts and context, until consensus was reached regarding each category (by PS, LW and JA). The reflexive process aimed to ensure trustworthiness of the code descriptions. Finally, all data were analysed cross-categorically by both PS and JA and synthesised to major themes.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted from the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (project number 7094), and Hatyai Hospital Ethics Committee (protocol number 47/58).

Results

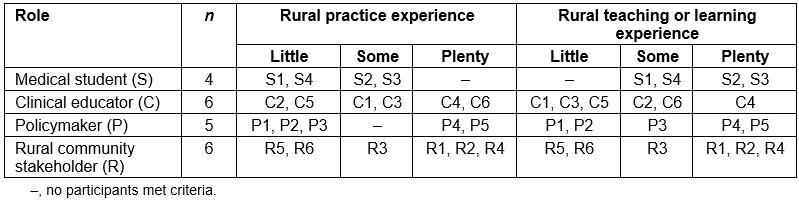

Twenty one purposively selected participants included medical students (S; n=4), clinical educators (C; n=6), regional health policy makers (P; n=5) and rural community stakeholders composed of three rural GPs, one rural nurse and two local community members (R; n=6). The participants demonstrated a range of rural practice experience, and rural teaching or learning experience across all groups (Table 1). Findings are presented below in two parts, first within the symbiosis axis categories (Table 2) and second as the results of the cross-category analysis of themes (Table 3).

Table 1: Participants classified by roles and level of experience

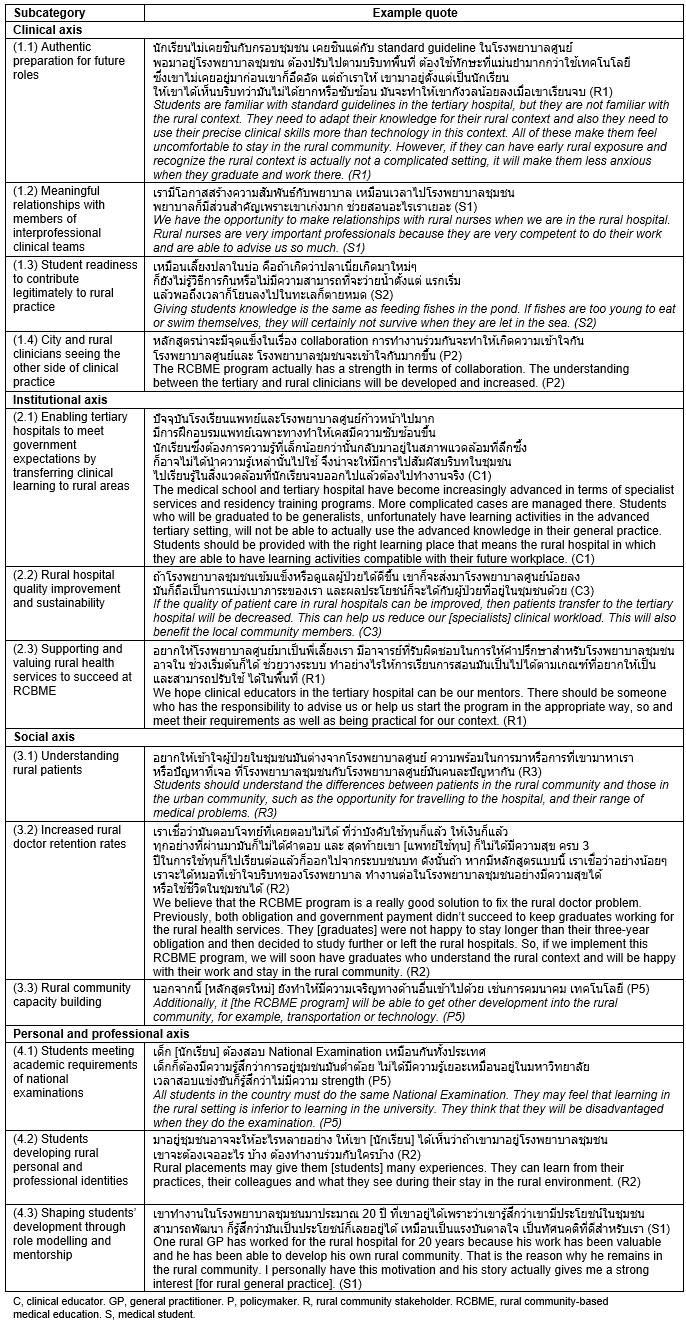

Table 2: Analysis by symbiosis axis: subcategories and example quotes

Part 1: Analysis by symbiosis axis

Results of the first round of analysis according to the symbiosis theoretical framework revealed stakeholders’ perspectives on each set of relationships and how these might manifest within an RCBME program. In each axis the subcategories (Table 2) define the hopes for the local expression of RCBME and challenges associated with these.

The clinical axis: clinician–student–patient relationship: Participants expected Thai RCBME would be able to provide students with an authentic preparation for future roles in rural general practice. Overall stakeholders described this as fit-for-purpose for students’ development of generalist competencies, and would allow students to be informed about the process of patient management in the primary health services and transfer to the tertiary hospital. It was thought that students would gain more clinical experience when they engaged with their clinician supervisors and patients in an active role allowing continuity of learning and patient care. Additionally, students could learn to value the expertise of other health professionals in rural areas and could broaden their perspectives of interprofessional practice. Furthermore, not only students, but also clinicians in different health services would benefit from understanding the perspectives of the different rural and city health services and develop professional relationships across these services through an RCBME program. However, rural community participants expressed concerns about students’ expertise in clinical practice and were not comfortable about student readiness to contribute legitimately to consultations, which they were concerned would take longer.

The institutional axis: university–student–health services: Participants recognised the potential for a Thai RCBME program, representing government investment and university support for rural health services, to be of benefit to both rural health services and academic centres engaged in the government’s CPIRD initiative. Through RCBME, academic centres in MoPH hospitals would be able to meet government expectations for the transfer of clinical learning to rural areas. Importantly, students would be able to integrate teaching from academics with their learning from general practice clinicians. Further, an RCBME program would enable specialists from the tertiary university hospital to collaborate with rural clinicians, contributing to improving rural health services. Closing the gap between urban and rural health services would be possible through providing better quality and safety of patient care. It was thought that enhanced urban–rural collaboration might increase the attractiveness of working in rural health services, improving the retention of rural medical workforce and potentially improving the sustainability of rural health services. In turn such improvements would support the success of the proposed Thai RCBME program. However, concerns were expressed about the feasibility of delivering an RCBME program in Songkhla Province – specifically, the need to improve the clinical education expertise and supervision skills of rural clinicians, and ensure availability of specialists from the tertiary hospital to support the proposed program. The proposed apprenticeship model of education typical of CBME programs was recognised as not the norm in Thai medical schools, where clinical exposure is typically through an observership (watch, listen and learn) and where the emphasis is on study and preparation for national examinations.

The social axis: government–student–community: Participants, particularly policymakers, agreed that an RCBME program could reshape the medical curriculum so that CPIRD students could be more engaged in rural general practice and rural communities. Participants hoped that students would recognise the perspectives of rural patients and understand their experience of illness through experiences not possible during the urban medical program, such as visiting their patients’ community, gaining insight into how their patients lived, experiencing the wisdom of local community and engaging in holistic care within the community setting. Participation in such experiences during an RCBME program could improve students’ interest in a rural career. In connecting medical students, academics and specialist clinicians from the urban context with rural communities and practitioners in the rural context, it was expected that the RCBME program would reinforce the government’s health policy to improve rural health, and contribute capacity within the health services and communities in rural areas.

The personal axis: professional expectations–student–personal principles: This axis considers the impact of RCBME on students developing professional and personal identities during their medical training. During rural clinical placements, students perceived that they would have non-hierarchical relationships with their rural clinician supervisors and could be comfortable to learn from them in preparing to become rural clinicians in the future. The rural clinical exposure (as described in the clinical axis), together with the closer relationships between students and rural supervisors, was seen as shaping students’ professional and personal identities through supervisors’ role-modelling and mentorship, influencing a positive decision regarding rural practice as a career. On the other hand, students had concerns about learning opportunities in a different setting, particularly whether being taught in a rural hospital context would meet the academic requirements of their national examinations. CPIRD students expressed anxiety that their individual time preparing for the national examinations would be decreased because of their clinical commitments learning with clinicians in the rural hospital, compared to their colleagues in the urban centre. Students thought they would need private time to prepare for these knowledge-based examinations with their urban colleagues, to ensure the high achievement needed to pass their national examinations and qualify for their medical practice licence.

Part 2: Across-category synthesis of major themes

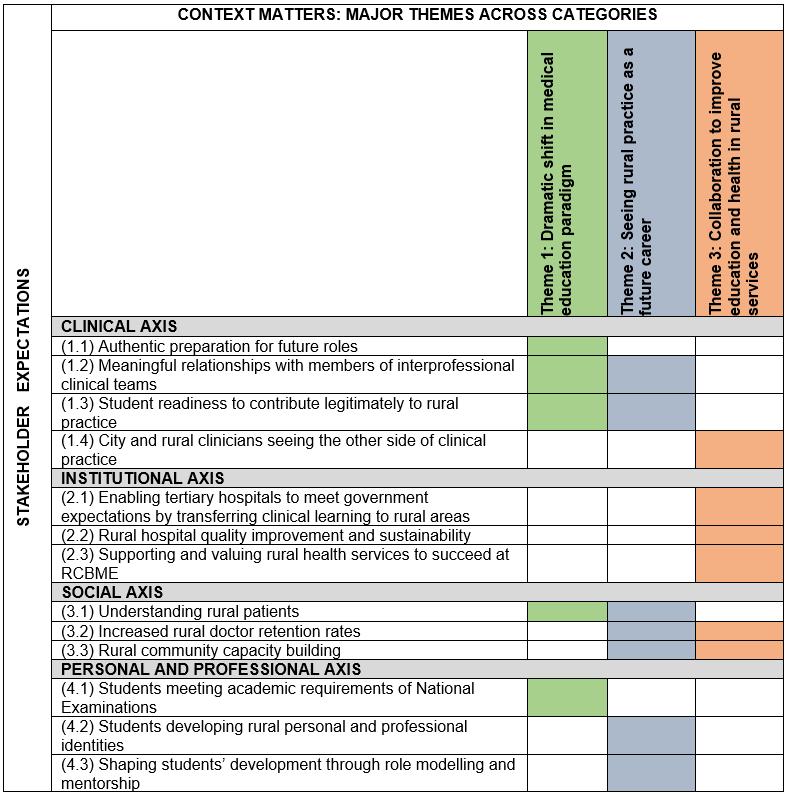

Synthesis across the symbiosis axes as previously described resulted in three emergent themes that integrated stakeholder perspectives on the implications of RCBME in Thailand (Table 3).

Table 3: Analysis of cross-category themes

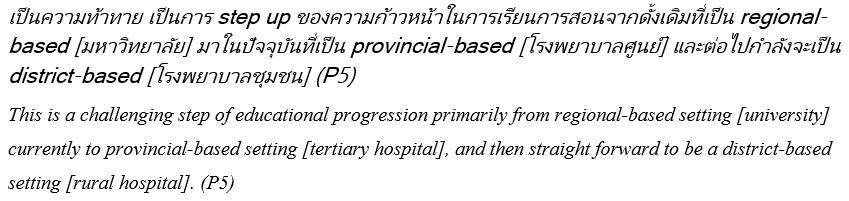

Theme 1: A dramatic shift in medical education paradigm: Participants recognised that the RCBME proposal was a significant new direction for Thai medical education. This shift included (1) a shift of location, (2) a shift of clinical content, (3) a shift of educational focus and (4) a shift of outcome.

Shift of location This educational shift directly involves moving undergraduate medical student training from urban-based tertiary hospitals to general practice based in rural hospitals and communities.

Shift of clinical content RCBME represents a change in the Thai medical educational content as students gain more access to patients with common conditions (including chronic diseases that are manageable in the primary care context) and patients with acute care conditions that need initial emergency management by rural doctors at the primary hospital such as acute trauma, and life-threatening medical conditions. Rural patients will potentially provide students with opportunities for greater authentic learning. Contact with patients over time may enable student–patient and student–practitioner relationships to develop.

Shift of educational focus RCBME provides opportunities to change the focus of medical education in the Thai context from traditional teacher-centred hierarchical models of education to more student-centred participatory learning.

Shift of outcome The main outcome shift was from exam-ready to work-ready. Thai stakeholders hoped that RCBME will prepare students to be ready for a professional career rather than focus only on academic preparation for written examinations.

Theme 2: Seeing rural practice as a future career: Participants expressed a hope, with caution, that if all stakeholders could envision an optimistic future for rural practice, then each group of stakeholders will positively reinforce the RCBME work and outcomes of each other. Their visions include a future for (1) Thai rural doctors as educators; (2) rural Thai patient health care and (3) CPIRD students as well-educated rural doctors.

A future for Thai rural doctors as educators Thai stakeholders generally expected that rural clinicians would be key people in delivering a RCBME program. In the future, rural clinician supervisors will be responsible for facilitating CPIRD students’ participation in clinical activities as clinical team members with non-hierarchical relationships among rural clinicians and other health professionals.

A future for rural Thai patient health care Rural patients were seen as important stakeholders in a Thai RCBME program and rural community placements more generally. Apprenticeship-style learning relies on rural sites having capacity for greater access to patients and, more importantly, patient willingness to participate in student consultations. Ideally, RCBME will be more successful if students are also welcomed by community members into the rural community and actively encouraged to engage. If Thai rural people and patients seek to support RCBME, then the program is more likely to produce doctors who are both competent in medical practice and have a deep understanding of the rural context.

A future for CPIRD students as well-educated rural doctors RCBME in the Thai context will most dramatically affect the experience of CPIRD students during their medical training. The success of an RCBME program will hinge on the acceptability of the program for this stakeholder group and how they embrace the opportunities to learn in rural areas. Student participants in this study saw that Thai RCBME could be a great opportunity for CPIRD students engaging not only with rural patients and health services, but also with local communities. Other stakeholders pointed out that students will need to be well prepared for their transition to the RCBME program because this will be a new way of clinical learning.

Theme 3: Collaboration to improve education and health in rural services: The final theme captures the sense of collective commitment expressed by the participants to work together across the rural–urban divide to ensure the success of RCBME. Collaboration between rural and urban stakeholders is anticipated to help improve rural health education as well as health services. The commitment to collaborate can be described at (1) an individual level, (2) an organisational level and (3) a community level.

Collaboration at an individual level This collaboration is expected to develop relationships between urban tertiary hospital specialists and rural clinicians who contribute directly to student learning, initially through interaction focused on supporting rural clinicians to develop their clinical education expertise and, further, in better supporting rural colleagues’ health service practice at rural hospitals.

In addition, the individual collaboration may enable rural clinical practice to be better recognised and understood by urban clinicians.

Collaboration at an organisational level Participants hoped the RCBME collaboration would enable tertiary hospitals to develop networks with rural hospitals, thus responding to the political strategy to improve rural hospital quality and sustainability. Academic networking for the RCBME program had potential to provide an organisational-level intervention, enabling rural doctors in different hospitals to develop clinical linkages, to work together as well as learn from each other to improve clinical care across similarly sized rural hospitals in the network.

Collaboration at a community level The RCBME collaboration would involve all stakeholder groups in provision of infrastructure to support travel, training and communication. If investment in the Thai RCBME enables community-level collaboration, then community ownership will influence the CPIRD project and government policies to create a sustainable RCBME model for Thailand.

Discussion

This qualitative case study demonstrates relevant stakeholder perspectives of a planned Thai RCBME program for CPIRD students in Songkhla Province, Thailand. The results in this study portray the hopes, expectations and concerns of stakeholders in terms of the four intersecting axes of the symbiosis model: clinical, institutional, social and personal. Emerging from this are three key across-axes themes: change in the medical education paradigm, change in the future of rural practice and collaboration at individual, organisational and community levels. These themes portray the meaning of the RCBME program within this case study of the Songkhla Province rural context. Stakeholder concerns point to the need to collaborate in coordinated planning, preparation and resourcing of the RCBME program if it is to succeed. These concerns and hopes are particular to this case and will influence development of the RCBME program in Songkhla Province, demonstrating the broader principle that context matters in implementation of RCBME programs.

The hope emerging from the stakeholder interviews is that successful implementation of RCBME will have a transformative impact on rural medical education, rural practice and rural community health in the province. The transformative potential for learning and building relationships is evident in the literature across a range of RCBME contexts4. One longitudinal study of RCBME described medical students’ transformative learning where they changed their world views, developing patient-centredness and deeper understanding of diversity20.

The authors acknowledge that the RCBME program in Songkhla Province is being developed during a time of dramatic shift in the medical education paradigm in Thailand. Despite challenges identified, the majority of participants in this case study demonstrated very strong commitment to the proposed RCBME program. The authors considered the potential that this finding relates to unique interest in RCBME of the study participants; however, the authors propose that this finding is better explained by Thai culture. Thai people generally hold deep respect for the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who showed a lifelong commitment to his people, particularly in rural areas of Thailand. He influenced his people to value education and sustainability. The unique context of this initial RCBME case study in Songkhla Province is also significant because the king’s father, Prince of Songkla, was a Harvard University trained doctor who did much to improve medical services in Thailand. This cultural history affects contemporary attitudes to the social conscience of Thai people and their attitudes to health and education.

Internationally, RCBME was initiated as an educational strategy in the Australian context in 1997 with the aim of improving the recruitment and retention of rural general practitioners (who, in the Australian context, have postgraduate speciality qualifications in primary care)21. This strategy included fostering medical students with rural backgrounds and early exposure to rural practice, with a view to encouraging more junior doctors to practise in rural communities7,21. In the Thai context, this educational change has significant implications including the need to adequately prepare students and rural clinicians for apprenticeship learning. Student concerns about the national examinations mean there is a need to consider the alignment of national assessment with contemporary clinical learning. Alignment of assessment with teaching is important to guide the desired learning behaviour22. The risk otherwise is that the desired apprenticeship learning of RCBME may be undermined by misaligned assessment. This is compounded in Thailand where the national examination is both highly specialised and administered in English.

For this RCBME pilot to be successful and the outcomes implemented across Thailand, it is important that key stakeholders continue to be consulted so that they embrace RCBME programs and see a better future for themselves. The international literature suggests many rural doctors choose to supervise students because they enjoy the professional company, intellectual stimulation and the opportunity to give back to the profession and shape the next generation23. However, there is evidence that being a preceptor for medical students needs to be feasible and economically viable24. In order for Thai rural doctors to take up this role and thrive in it, they must envision a positive future and be supported to co-create this future with RCBME leaders and other stakeholders.

Interestingly, community members’ willingness to be involved in a student consultation in this study was somewhat cautious because of concerns about student readiness to legitimately contribute to rural practice and concern about consultation time pressures because of the extra time required for student consultations. These concerns contrast with the international literature, which has found that patients usually report enjoying the additional time they have with students and clinical teachers during parallel consultations25. The time pressure that Thai local community members were concerned about may indicate participants’ experience of inadequate rural health service capacity due to medical workforce shortages. Patients will need to be supported to see that RCBME does not reduce their access to care, and that having additional time to discuss with medical students can add value to their care. Patient engagement and consent to see medical students will also need to be actively managed. Evaluation of the impact on patients will be important for providing feedback to engage community members.

Encouragingly, CPIRD students saw RCBME had the potential to improve medical competencies through authentic actions and experiences in rural clinical practice. Medical students can move from being theoretical learners to junior health service providers through participating with their clinical team26. Longitudinal experiences can allow comfort, familiarity and trust to develop in relationships between students and their preceptors during their clinical placements27,28. Moreover, students can meaningfully engage with patients and take responsibility for their clinical care under supervision27,29. Situating medical students within the context-rich environment of RCBME allows for meaningful relationships and experiences, which can enhance learning both in relation to practising medicine and becoming a doctor8.

Thai RCBME initiatives will succeed through meaningful collaboration between urban and rural stakeholders, which in turn can improve a broad range of rural education and health services. At an individual level, tertiary hospital clinicians and rural doctors can work together to progress the medical education expertise of rural GPs and provide complementary teaching to students. Internationally, rural clinicians appreciated their relationships with the universities and students, taking great pride in being part of the academic endeavour of helping to train the future generation of doctors30. Rural clinicians have reported gaining personal satisfaction from continuity of supervision in RCBME programs7.

Cooperation between rural health services and tertiary hospitals will be required to ensure that the service expectations of specialists include time and resources to enable visits to rural hospitals, and that rural hospitals have the capacity to improve health services in response to new knowledge and systems. This requires high-level organisational collaboration and commitment to the shared goal of improving rural health. In Australia, a decade of government investment in rural clinical schools has had an extensive positive impact on rural and regional communities, including the development of teaching facilities, increased access to technology for hospitals, development of community groups involved in health promotion and education, a retained and expanded clinical workforce with increased academic status and, importantly, rural research capacity to progress the health agenda in rural and remote areas31,32.

Finally, collaboration at a community level for RCBME will also strengthen the local community capacity. Considering the Thai context specifically, to ensure the RCBME program is possible and sustainable, the Thai government must work with the relevant stakeholders to facilitate the development of infrastructure in rural health services contributing to rural education. Internationally, socially accountable medical schools have sought to produce graduates who are work-ready for the communities in which they will be employed, and simultaneously have sought to improve the health of the communities in which they train their students through improvements to health services and in community development more broadly33. This potential for a positive impact on Thai rural health is not unrealistic. One study in a similar underserved rural context reported the association between the formation of an innovative medical school in a low-resource, developing-world setting, recruiting students from the local region, and a significant reduction in infant mortality, which is a major problem in the rural and remote regions of the Philippines16. This required community support and cost-effective investment by the government to sustain the quality of the local hospital in such a poor rural area16. Another study, in the resource-poor context of Nigeria, described how community stakeholders perceived their local healthcare services had benefited from having RCBME medical students34. The findings of the present study demonstrate that Thai stakeholders in RCBME are interested in improving rural health outcomes. It is vital that the Thai RCBME program leadership seeks engagement of the community and ensures ongoing government interest and investment in RCBME. Based on the findings on stakeholder views, program development should include ongoing commitment to, and evaluation of, improvements in rural health service capability, quality and sustainability.

As discussed in three across-axes themes, in comparison to the international evidence, specific differences found in the Thai context that have implications for RCBME in Thailand will need to be considered; thus, context does matter when introducing educational innovations to a new context.

Limitations of the study

Although this case study was conducted solely in the geographical context of the southern region of Thailand, it considered that the context of medical education in broad terms consistent across Thailand in terms of medical course student selection, medical curriculum framework and national assessments at the completion of medical school. The results may well be translatable to other institutions in other parts of Thailand. Further studies regarding RCBME in other regions of Thailand, including a wider range of relevant stakeholders, should be performed in order to confirm and strengthen the results of this study. The broader argument that understanding the health and community context prior to implementing new CBME programs is essential for adapting RCBME to context is likely to be the case elsewhere. Another study limitation is that while this case study represents a snapshot in time, prior to the implementation of RCBME in Songkhla Province, it is likely that the views of these stakeholders will evolve over time. Regular multi-level engagement and consultation with stakeholders is recognised as an important part of continuous quality improvement and finding local RCBME solutions35.

Conclusion

This study comprehensively describes Thai stakeholder views of RCBME and demonstrates that, although some principles of RCBME are universal, context does influence the expectations, concerns and the capacity of stakeholders to contribute to RCBME. Prospective formal stakeholder engagement is recommended as an early step in the implementation of new educational innovations to engage key parties, understand different perspectives of success and enable stakeholder relevant evaluations to be instigated.

To ensure successful implementation of this educational innovation in Songkhla Province and translation of this innovation to other regions in Thailand, further studies, both research and evaluation, on RCBME outcomes and stakeholder experiences are recommended to ensure the stakeholder expectations about the RCBME initiative described in this case study are delivered.