Introduction

In most Western countries, occupational therapy is an established profession in the rehabilitation field and a crucial aspect of overall health care1. Within low–middle-income countries2 it is an emerging profession, with most rural and remote areas in need of more occupational therapy services1.

Occupational therapy as a profession is taught and practised in accordance with relevant local, national and international contexts3 and is an accredited qualification that requires a university education (not available in many low–middle-income countries).

The Solomon Islands is the second largest archipelago in the South West Pacific, bordering with Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu. The nation is predominantly Melanesian (93%) and the population is growing by 2.3% per annum, projected to be 667 044 in 20184. It is one of the least developed countries in the world with a GDP of US$645 per capita in 20085. Limited economic resources, political instability and significant natural disasters have negatively impacted on the health of Solomon Islanders.

The majority of the population (80%) live in rural and remote areas, with limited access to basic services, including drinking water, sanitation, electricity, education facilities and health services5. Thus the overall health status of those living in rural and remote areas is worse than that of urban Solomon Islanders.

A large percentage of the population are in the younger age groups, with 41% younger than 15 years and only 5% older than 60 years4. This indicates that people in the Solomon Islands are dying younger of diseases that are preventable. Regardless, there have been steady benefits to population health outcomes due to policy changes and investment in health, with an increasing life expectancy (from 59 years in 1980 to 71.1 years in 2018). However, this change, combined with a high prevalence of health risk factors and increasing rate of non-communicable diseases/disabilities, is putting increased pressure on the health system6.

The National Referral Hospital (NRH) is based in Honiara and over 70% of the health specialist workforce is employed there. Health care to the remainder of the Solomons (the majority of the population) is provided via seven provincial hospitals, community clinics and aide posts7. However, the health facilities are severely limited by a lack of resourcing, are in need of repair and upgrade and have shortages of supplies and well-maintained equipment6.

The medical needs of the rural and remote community are serviced mainly by a trained nursing workforce and a lesser number of doctors6. However, through government-based initiatives, community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers are having an increased positive impact in rural and remote areas in terms of rehabilitation needs7.

To date, there has not been enough focus on workforce planning in the biomedical and allied health professions6. Allied health services available at the NRH in Honiara include physiotherapy, speech therapy and occupational therapy. Occupational therapists (OTs) engage with people and communities, working with them and their environment by promoting health and wellbeing, so that people are able to engage in the everyday life activities that they need to, want to and are expected to do8. This engagement includes enabling participation in community, social and civic occupations including self-care, interpersonal relationships, education and work3.

The department of occupational therapy at the NRH was established in 2004 by an Indigenous OT. Occupational therapy services are mainly hospital based, with some community outreach. The Indigenous OT had relocated overseas prior this research. At the time of this research in 2010, a sole expatriate volunteer OT practising in Honiara (but not at NRH) was interviewed. By 2015, the OT department was occupied by a CBR worker.

University-level occupational therapy, physiotherapy or clinical exercise physiology qualifications are not available in the Solomon Islands so the majority of university-trained allied health professionals are expatriates, of which the numbers at any one time are small and variable. However, local Solomon Islander workers were recruited in the 1990s to train as CBR workers, and there now exists a 2-year program for locals, accredited by the then Solomon Islands College of Higher Education, now called Solomon Islands National University, which is taught by expatriate OTs and physiotherapists (of which one physiotherapist is local)1. The goals of CBR education are to equip graduates with the skills to implement CBR strategies at a provincial level. The programs have a strong focus on supporting people with disabilities through social inclusion, empowerment and health promotion9.

The World Federation of Occupational Therapists is not able to estimate the numbers of expatriate and local CBR practitioners in low–middle-income countries10, but the Solomon Islands currently have approximately 20 or more practitioners. CBR is a strategy whereby people with disabilities can attain equal opportunities, social integration and rehabilitation, facilitating their access and participation to services such as education, vocation and health as both consumers and providers9,10. As such, CBR is an appropriate health strategy for the Solomon Islands10.

CBR programs running under the Ministry of Health help address the health needs of the community. Churches and local and international non-government organisations also provide some rehabilitation interventions11,12. There are, however, a lack of specific allied health services that can deliver and support adequate levels of health interventions in either communities or hospitals. Rehabilitation is an essential aspect of a holistic community health approach and the occupational therapy profession is at the forefront of any effective allied health service10. Although these CBR-educated workers help meet the rehabilitation health workforce needs, to be as effective as possible they require the support of qualified allied health staff.

Like other Pacific Island nations, the Solomon Islands is experiencing a double disease burden with high levels of communicable disease, layered with an increasing incidence of non-communicable diseases. This increase in disease burden will contribute to the growing inequity in health between the Pacific Island nations and the rest of the world unless health resourcing and provision factors are addressed13.

The number of deaths from specific causes in low–middle-income countries is estimated from incomplete data but the majority of the top 10 causes of death in these countries are from communicable diseases, maternal causes, and neonatal and nutritional conditions, with lower respiratory conditions estimated to be the highest cause of death in these countries, with ischaemic heart disease and stroke the second highest and road traffic injury third14. Those who survive are often left with minor or major disability. A report from the Ministry of Health shows that around 14% of the Solomon Islands population have a disability4.

The high levels of disability, combined with an increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases and an ageing population, suggests that the need for effective disease management and rehabilitation services will increase in the Solomon Islands over time5.

To address these priorities, allied health professionals including OTs have to work across disciplinary boundaries, often into the realm of health promotion. Low–middle-income countries are challenged by limited access to appropriate resources and services10. Health professionals face professional challenges including diverse clinical caseloads, remote and large geographic service areas, a scarcity of resources, lack of prioritisation of rehabilitation services, lack of professional support and development opportunities, professional isolation and a perceived lack of management support12. Subsequently, the recruitment and retention of allied health professionals, including OTs, presents a constant challenge2,12. Moreover, the applicability of Western theoretical models, which currently guide OT practice in the Solomon Islands, has been questioned15.

This project investigated the role of occupational therapy in the Solomon Islands by examining the experiences and perceptions of OTs and other rehabilitation health workers who have current or prior experience working there. It aimed to provide recommendations for the enhancement of health and sustainability of rehabilitation services through the occupational therapy lens. Although this project is focused in the Solomon Islands, the findings have relevance throughout the Pacific Island nations.

Methods

A qualitative design was chosen, informed by a phenomenological approach, which aimed to describe the subjective experiences of the participants16. Participants all had experience working in the Solomon Islands in the area of rehabilitation and were purposively identified and selected in consultation with an Australian based OT (third author; who had worked in the Solomon Islands for 2 years). The identified potential participant names were submitted to Australian Volunteers for International Development (AVID) for contact details. Although no longer operating, AVID was an Australian Government initiative that aimed to provide assistance to low–middle-income countries as part of an aid program. Recruitment was undertaken via direct contact by the first author. Purposive sampling resulted in three potential participants, and through snowballing seven more participants were recruited.

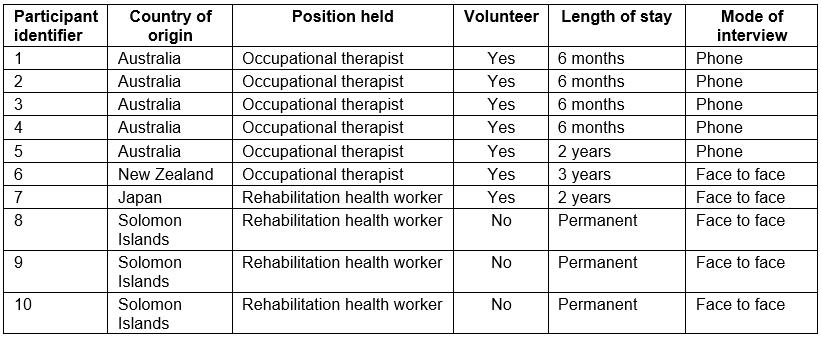

Participants were formally invited by email with an information sheet and consent form attached. Interested participants returned their signed consent form before an interview was arranged. Interviews were conducted by the first author (in Australia) over the telephone or in person (when the first author was in the Solomon Islands) and lasted from 12 minutes to 1 hour (Table 1). Interviews were recorded with the participant’s consent. Interview questions were formulated from the literature review and the research aim and were piloted. The following questions were asked:

- What is the role of occupational therapy in the Solomon Islands?

- What are the experiences of OTs who are currently working or have previously worked in the Solomon Islands?

- What are health workers’ perceptions of OT services in the Solomon Islands?

Interviews were transcribed and translated from Pidgin to English by the first author (who is an Indigenous Solomon Islander). Transcriptions were coded and categorisations were manually identified by grouping words or sentences. Thematic analysis was used to generate themes from the interview data16,17.

Trustworthiness of data was ensured via credibility, confirmability and dependability. The phenomenological technique of utilising additional sources for data18 ensured that credibility was achieved through triangulation. This entailed in-depth interviews, direct observation and field notes. Field notes19 were obtained when the first author spent a day with the sole OT working in Honiara during the research period. One participant mentioned that they recorded daily diary entries whilst working in the Solomon Islands, and consent was obtained to include these entries as a data source. Other methods of rigour include member checking (which enhanced confirmability) and the involvement of all three authors in data analysis and verification of the decision trail (which enhanced dependability).

A total of 10 participants were interviewed. They consisted of OTs (n=6) and related rehabilitation health workers (n=4). All of the OTs had worked in the Solomon Islands under the AVID program.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Solomon Islands National Research Health Ethics Committee (NRHEC) and the James Cook University Human Ethics Committee (approval number: H3682). Informed consent was gained from all participants.

Results

A summary of the demographics of the participants of this research is given in Table 1. Two main themes were derived from the transcripts: the diverse roles of occupational therapy in the Solomon Islands and challenges related to professional practice in the Solomon Islands.

Table 1: Participant demographics

Theme 1: The diverse roles of occupational therapy in the Solomon Islands

The different roles identified were in the areas of ‘education’, ‘community OT’, ‘acute physical and psychosocial rehabilitation’ and ‘project management’.

Education: All of the OTs interviewed took part in providing education to different groups across a range of settings including parents, classrooms, schools, tertiary providers, hospital and in the community. Educational activities included teaching CBR students (specifically, those undertaking the Certificate in CBR Studies at the then Solomon Islands College of Higher Education), supervising practice placements, coordinating mental health awareness workshops, and running basic health education sessions and workshops on disability. The OT role as an educator was summarised by one therapist as:

… curriculum development, liaising with education authorities, networking with relevant government funds or authorities, communicating with donor agencies … (OT5)

Teaching parents of children with a disability in a school setting was also identified by one therapist.

A lot of Cerebral palsy and a lot of contractures were developed from poor positioning [thus, the occupational therapists taught parents on] how to position and carry their kids … (OT1)

Community occupational therapy: Providing support, networking, resources and training was seen as essential for community capacity building. OT3 stated that ‘ … the main idea was to build the capacity of CBR workers’ in the community. More specifically, OTs participated in health promotional activities such as diabetes education, conducted home visits and trained local staff on ‘…how to source equipment and how to prescribe it appropriately …’ (OT3).

Acute physical and psychosocial rehabilitation: The role of occupational therapy was very broad and encompassed ward-based and service development work, establishing psychosocial programs for the rehabilitation of clients with chronic mental health disorders, and networking with external organisations and community mental health nurses.

… we did some generalised case load of developmental work, like children with CP [cerebral palsy] to hand therapy to neurological rehab with stroke and meningitis, spinal cord injury and home visiting. (OT4)

The diverse setting provides an opportunity for the OT to acquire many essential and cross-cultural skills within a short period of time.

As identified by one participant:

I feel like I have gained three years of skills in a year’s work. (OT4)

Two health workers perceived occupational therapy as an integral part of the rehabilitation of clients:

It is true that a physiotherapist can do little functional activities, but it also necessary for occupational therapists to do the functional, finer motor movements as part of the rehabilitation services. (translation from Pidgin, HW1)

Project management: One participant identified a project management role that may lead to further research:

… [developing a] survey tool, consultation with a multi-sectoral steering committee, training of surveyors, training of volunteers in the field, supervision of data collection in the provinces, data analysis and report writing. (OT6)

Theme 2: Challenges and strategies related to professional practice

Six factors were identified relating to professional practice: ‘availability of resources’, ‘communication strategies’, ‘professional practice models and challenges’, ‘professional support’, ‘cultural safety’ and ‘lack of knowledge about occupational therapy’.

Availability of resources: The health workers and OTs were very creative and used available resources. Western equipment did not always fit the environment, thus local materials were utilised. Using and adapting local materials are both efficient and practical for the therapist and the client because ‘people cannot afford to get from the edge of town into hospital … five days a week for treatment’ (OT4).

This quote shows that initiative was seen as necessary to adapt available resources. For instance, under the guidance of a therapist, CBR students ‘developed a resting splint from coconut and pieces of wood and plastic bowls’ (OT2). A lack of technological resources such as the internet also impacted on CBR students’ and therapists’ ability to research information and improve professional knowledge.

Communication strategies: Communication strategies were developed to reduce the language barriers. These included having a wantok (friend, relative or carer) translate. Alternatives were ‘…visual aids rather than verbally communicate with teacher or parent’ (OT2) and ‘… gesture and/or drawing’ (OT4). Learning and speaking Pidgin was considered essential, and mixing with Pidgin speakers was a strategy used by therapists. ‘Local people were responsive and supportive when OTs made efforts to learn pidgin’ (OT5).

Professional practice models and challenges: Western models or standard assessments did not translate well to the cultural setting of the Solomon Islands. For instance, the inclusion of people with disabilities and support for workplace inclusion ‘was not relevant to the Solomons’ setting because of the environment’s infrastructures available’ (OT3). People with disabilities rarely participate in the workforce. Therapists did, however, identify aspects of professional practice that could be translated culturally and across professions. For example, occupational therapy specific screening tools and scales were adapted and explained to ensure translatability of the therapists’ work to ensure ‘… [the multidisciplinary allied health team and/or] local nurses could continue with this work’ (OT6).

Professional support: Building in-country and other relationships and professional networking was important for moral and professional support. One OT highlighted that ‘I was lucky that I had met the people at CBR … they were always there to support me’ (OT2).

Our hope is that for [an] OT [working] in the Solomons, that [a] relationship is established with someone from Australia or from somewhere [so] that they can link up with therapists there … to support the therapist in the Solomons … so that you don’t feel you are alone. (OT4)

Cultural safety: Most therapists identified the importance of culturally safe practice. It was highlighted that when cultural safety was not practised, the intervention was unsuccessful:

… it was on those days and I’d walk away and go wow, it didn’t work because half the time I wasn’t thinking and yeah, you can definitely tell when you aren’t conscious of it … (OT2)

Therapists developed strategies to improve cultural safety: ‘[I] asked lots of questions, and [worked] with local staff wherever possible, in order to be culturally appropriate’ (OT6). Several participants identified cultural aspects as being contrary to the goals of rehabilitation. For example, the cultural duty of wantok plus a differing understanding of disability as ‘sickness’ tended to foster dependency. They also identified that the close extended family system can compromise confidentiality.

Lack of knowledge of occupational therapy: Health workers identified a lack of knowledge about occupational therapy in other health professionals and the community, which has implications for the future development of the profession in the Solomon Islands: ‘Doctors in the country who work with all kinds of deformities need to be educated about the role of occupational therapy and its importance’ (translated from Pidgin, HW4). Participants also raised the need for an Indigenous occupational therapy workforce in order to provide culturally appropriate services.

Discussion

The overarching aim of this research was to investigate the role of occupational therapy in the Solomon Islands by examining the experiences and perceptions of therapists and other rehabilitation health workers. Uniquely, this project used the occupational therapy lens to provide insight into health promotion and sustainability of rehabilitation services in the Solomon Islands.

Two overarching themes were found: the diverse roles of occupational therapy in the Solomon Islands and challenges related to professional practice in the Solomon Islands.

This project identified broad-ranging and important roles undertaken by the therapists, including health promotion. In the Western paradigm, occupational therapy is not traditionally viewed as a health promotion discipline; however, the ‘upstream’ approach focuses on fixing the health problem at its source20. It acknowledges that health promotion is multi-sectorial, encompassing influencing socioeconomic and environmental factors, social and health supports and the education system, all aspects that have been identified as roles undertaken by participants in this project.

Given the limited numbers of qualified OTs in the country, perhaps the most important role identified was that of support and education of CBR workers in the areas of chronic disease management, rehabilitation and disability (physical and psychological). The World Federation of Occupational Therapists recognises that training and education of consumers, their families and communities is an important role of the OT in facilitating and developing CBR programs10. Participants recognised the importance of this role and strived to find local solutions to local problems and create a context for reciprocal learning to ensure culturally appropriate interventions21. In addition, the leadership role of OTs in legislation and policy development is advocated for in order to improve access across the board for people with a disability8. As the need for rehabilitation services becomes larger in the Solomon Islands, it will be increasingly important to ensure an adequate OT presence in the country.

This study highlighted the lack of knowledge about the value of occupational therapy. Similar challenges introducing a ‘new’ profession in other low–middle-income countries were identified in the Dominican Republic22, Vietnam23, Laos24, Ghana25 and Haiti26. Actively engaging other health professionals and the general public through a disease management and rehabilitation awareness campaign would be a useful strategy.

The need for developing an Indigenous occupational therapy workforce was raised by many participants. Establishing domestic training opportunities is one way to develop a sustainable occupational therapy service9,11,21,22, especially in relation to identifying pathways through secondary schools.

In relation to challenges, the therapists interviewed enjoyed the creativity, varied caseloads, community spirit and geographic diversity of working in the Solomon Islands. However, the cultural application and usefulness of Western theoretical models and more traditional practice in these non-Western settings was questioned and has been previously discussed in the literature1,2,15,21,22.

In Melanesia, wantok refers to a pattern of networks and relationships that link families and communities. For rural areas in particular, wantok is a concept of identity that provides social capital and outlines obligations27. The cultural duty of a wantok or carer for a sick person was often in conflict to therapy goals of increasing independence and function1,15. Similarly, differing cultural concepts of disability (equating disability with sickness and restricting the activities of people with a disability) have been identified previously1,15,22. The challenge of confidentiality in open family kinship groups and local workers has also been identified in the literature1,22.

Therapists came up with pragmatic strategies to overcome these cultural differences and resource limitations. Self-awareness and a willingness to be flexible and open to attitudinal change are essential characteristics of therapists wanting to work in a culturally diverse context1,21,22. Therapists in this project used strategies such as flexibility to address differing concepts of timeliness, and awareness and education workshops to address differing Indigenous attitudes to health care. In addition, the willingness to learn to speak Pidgin was acknowledged to improve therapy outcomes. These strategies underline the importance of culturally safe practice as an integral part of practice1,21,22.

As previously found for other countries1,23-25, given that most people live in rural and remote areas, the physical environment and geographical location of the Solomons was a challenge to both service delivery and professional development. Participants identified the need for ingenuity when utilising local materials in a resource-limited environment and the need to ensure translatability of tools and practices across cultural and disciplinary divides, which is in line with the literature23. Professional support too required ingenuity. The utilisation of other health workers for support was a useful strategy in this research, and this approach has been advocated for use by OTs working with community-based organisations21. Journalling of experiences has also been used as a way to make meaning of experiences working in a majority country22, and it has been suggested that professional support is particularly important for newly graduated OTs23 and indeed any health professional establishing a new service in a low–middle-income country25.

Limitations

This project was limited by the low number of available participants; however, the triangulation of themes via different methods and sources enhanced the rigour of the findings. It is acknowledged that findings are specific to occupational therapy in the Solomon Islands over a limited period of time. Further research could focus around the experiences of a range of allied health staff and more CBR workers to provide additional information that could help guide rehabilitation education and practice in the future.

Recommendations include:

- government strategies around promotional activities to increase awareness of the occupational therapy profession, and the importance of chronic disease management and rehabilitation

- strategies that enhance the training opportunities of Indigenous therapists (eg universities in the Solomon Islands developing mutually beneficial global partnerships with education institutions in developed countries)

- promotion and teaching of pragmatic strategies to overcome cultural, geographical and resource challenges (eg expatriates learning the relevant language).

- utilising OTs as key educators and supporters of other CBR workers (eg translating and sharing practices across disciplines)

- expanding the leadership role of OTs in-country and elsewhere to promote and advocate for disease management and rehabilitation services, and opportunities for people with a disability to contribute at a legislative and policy level.

Conclusion

The significant role of occupational therapy in the enhancement of health and sustainability of rehabilitation services in the Solomons was revealed through the various tasks undertaken by OTs, including influencing health policy and practice broadly through advocacy and education. The ageing population and double disease burden being experienced by the Solomon Islands will lead to a growing need for rehabilitation services, therefore it will be increasingly important to ensure an adequate OT presence in the country. Further research into occupational therapy and other allied health roles in relation to health promotion and rehabilitation in majority world countries will help determine the relevance of these recommendations throughout Pacific Island nations.

References

You might also be interested in:

2019 - Social and community networks influence dietary attitudes in regional New South Wales, Australia

2008 - Health behaviors and weight status among urban and rural children