Introduction

Worldwide, in 2008, approximately 41% of pregnancies were unintended (defined as occurring two or more years sooner than desired, or unwanted). This percentage varied widely, from 30% in Western Africa to 64% in South America. Negative outcomes of unintended pregnancy can include delayed prenatal care, a reduced likelihood of breastfeeding, contributing to unhealthier children, and a higher risk for intimate partner violence during pregnancy1.

Although it has declined in the last 20 years, unmet need for contraceptives is still relatively high in many regions of the world2. Bellizi et al found that in many low–middle-income countries, over 65% of women with a current unintended pregnancy had not used a modern contraceptive method, and long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) use was low. Increased contraceptive access and increased patient counseling could have helped ensure higher contraceptive uptake3.

In 2010, Church et al. identified factors that contributed to the integration of sexual and reproductive health care into primary care in developing countries4. The review highlights the diversity of services needed, including outreach and education beyond traditional clinic-based services. A coordinated, systems-level approach is needed to properly integrate sexual and reproductive health care into primary care in developed countries4.

In Europe, Ketting and Esin found that sexual and reproductive health care is often poorly integrated into primary care. Depending on the country, women receive their sexual and reproductive health care with a family doctor or primary care provider, from a multidisciplinary team, from a private gynecologist or in a hospital setting. In the countries where sexual and reproductive health care is provided through hospitals, clinics and gynecologists, sexual and reproductive healthcare services are not integrated into primary care. Ketting and Esin recommend that primary care providers take greater responsibility for providing sexual and reproductive health care, and coordinate care as needed5.

The current case study focuses on the USA. In the USA, approximately 45% of pregnancies are unintended6. Unintended pregnancy rates for low-income women are consistently higher than for women of other income levels6. Despite a multitude of interventions at the federal, state, and local levels, unintended pregnancy rates steadily increased among low-income women from 1981 to 2008, with a slight decrease between 2008 and 2011 in the US7.

Accessing quality contraceptive services can be a barrier for some individuals, especially low-income, uninsured, minority or younger women. These problems are exacerbated in rural areas1. Barriers to accessing services in the USA include cost of services, lack of insurance, clinic locations and inconvenient clinic hours, lack of awareness of contraceptive services, and no or limited transportation1.

Integrating reproductive intention screening, contraceptive counseling, and the provision of contraceptive services into primary care is an approach recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Office of Population Studies through their Quality Family Planning Guidelines8, to ensure that all sexually active women seeking primary care services receive access to comprehensive contraceptive methods. Power to Decide’s One Key Question9 offers a patient-centered approach to guide practitioners on how to start the conversation with patients about pregnancy desires.

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are community-based health clinics that provide healthcare services in medically underserved areas in the USA. FQHCs serve the underserved, underinsured, uninsured and non-citizens – mostly low-income populations. FQHCs are mandated by law to provide ‘voluntary family planning’ as a required primary care service and, with the passage of the Affordable Care Act, are becoming increasingly important in the delivery of these services10. In 2010, 16% of all women obtaining contraceptive services did so at an FQHC10. This percentage has likely grown since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. However, there is wide variability among FQHCs as to the types of services that are offered. This is due to size of the FQHC, funding, and priorities. Many FQHCs, especially small ones located in rural areas, offer limited access to LARCs and other family planning resources11,12.

Twenty-five Virginia counties are considered part of Appalachia, a mountainous and rural region located in the eastern part of the USA13. Approximately 8 million people live in Virginia, about 1 million of whom are living in rural areas14. Many of the people living in these rural communities lack adequate access to high quality primary and preventive healthcare services. Several studies indicate that rural residents experience more disparities, and are older, poorer, and have access to fewer primary care providers. Rural residents are less likely to have healthcare coverage provided by their employer, and often rely on safety-net programs and Medicaid, increasing health disparities15.

In some rural communities, the political and cultural climate of the community, along with conservative federal and state laws, may impact the provision of family planning services. This may include providers refusing to provide certain types of contraceptives and having personal conservative values towards family planning. The perceived demand for services and local attitudes may influence health center decisions on what services to offer16. Several FQHCs have reported that the community political climate was often a challenge in providing services17. In rural communities, patient transportation to services, in addition to low patient literacy and patient adherence and compliance, are seen as barriers18.

For many FQHCs, especially the smaller rural ones, community outreach and education are little to non-existent, due to a lack of funding16,17. With many FQHCs having limited resources, they are often not allocated to outreach or education. This results in many patients not knowing about available family planning services; this low level of community knowledge about services is a barrier to some FQHCs17. Systematically screening for reproductive intention and offering contraceptive counseling may reduce this knowledge barrier.

Virginia Family Life education standards include ‘abstinence-only until marriage’ education in all grades. All school districts in Virginia can decide to add evidence-based education to their curricula, but many do not. Political pressure from conservative groups to adhere to the strict ‘abstinence-only until marriage’ guidelines means that many students do not get science-driven, evidence-based family life education.

Fox et al. found that federal abstinence-only funding had a negative effect, increasing adolescent birth rates in conservative states, but that comprehensive sexuality education funding helped reduce adolescent birth rates in those conservative states19.

In three of the counties served by this FQHC in 2017, 32%, 48.6%, and 49.7% of high school students (ages 14–18 years) reported having ever had sexual intercourse (Sallee D, unpublished data, 2017). Of all high school students reporting ever having had sexual intercourse, slightly more than half reported using a condom at the last sexual encounter in all three counties. In one county, 12% of sexually active students reported not using any sort of method to prevent pregnancy or STDs at their last sexual encounter (Sallee D, unpublished data, 2017). These data show a potential unmet need for education and contraceptive services in the region served by this FQHC, specifically the service region for the case study site.

Methods

The case study site was identified through purposive sampling. This site was selected because it is an example of how a healthcare organization located in a rural, conservative part of the USA has been integrating contraceptive services into primary care. This FQHC also offers the unique perspective of offering integrated services in rural Appalachian counties.

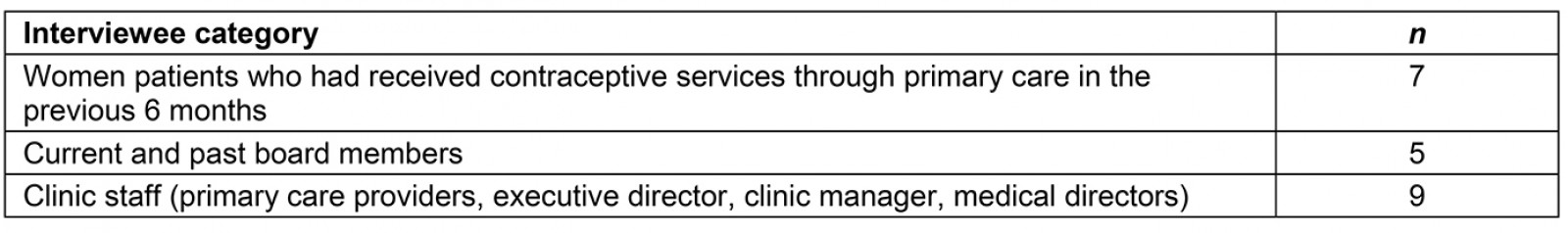

All women patients who had received contraceptive services through primary care in the previous 6 months were invited to participate in a semi-structured phone interview. Two out of 22 women participated (response rate 9%). An additional five women patients at the clinic were interviewed in person over the course of two afternoons (response rate 50%). Patient ages were 19–35 years with a mean of 26 years. Patient names were identified by the clinic manager and women were invited to participate in the study by the primary care provider. The principal investigator was not affiliated with the clinic and completed this research as part of their dissertation work.

A sample of current and past board members was invited to participate in semi-structured interviews. All five board members identified agreed to participate in an in-person or phone interview (response rate 100%). Board member names were identified by the executive director and were invited to participate by the principal investigator.

A sample of five primary care providers and nurses (a family nurse practitioner, registered nurses and a doctor of osteopathic medicine) who interact with women receiving contraceptive services was invited to participate in a semi-structured in-person interview. Additionally, the executive director, the clinic manager, and the current and past medical directors were interviewed. All nine respondents agreed to participate (response rate 100%). Staff names were identified by the executive director and were invited to participate by the principal investigator.

A total of 21 interviews were conducted. Interview questions revolved around the provision and delivery of comprehensive contraceptive services, accessibility of services, patient knowledge of birth control, patient knowledge of services, health center staff training, health center communication, and health center client population.

All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and uploaded as Word documents into Atlas.ti®. A hybrid of deductive (a priori) and inductive coding methods was used for theme generation. In following the deductive method, a series of potential codes to look for was determined ahead of time to help identify emerging themes based on a preliminary data analysis of the survey. A total of 37 a priori codes were developed. A priori codes were developed based on an extensive literature review.

Following an inductive coding method, new themes that emerged during the data analysis process were coded, compiled, and summarized. Thirty-two emerging codes were documented.

Coding was conducted by two independent coders after all interviews had been completed. Coders read the transcripts once, and then initiated the independent coding process. The second coder coded a subset of all interviews. The coders used the a priori codes and looked for emerging themes common to all questions, between documents and between respondent categories. After both coders completed coding and assigning themes, these were compared. A final list of themes that encompasses the main codes from both coders was developed. Important points and themes were summarized and presented as evidence to document the functioning of this FQHC. Major themes that emerged included, ‘lack of knowledge of services offered’, ‘lack of knowledge about birth control and reproductive health’, ‘misinformation and misconceptions’, ‘education on birth control’, and ‘care model’ and are described in detail in the results section.

This aim of this study was to document how one rural FQHC adapted to their culturally conservative environment by offering contraceptive counseling, comprehensive education on birth control, and access to contraceptive services directly through primary care. This FQHC’s integration of contraceptive services is a model that can be replicated by other FQHCs, by local health departments, or by private physicians.

Table 1: Interviewee characteristics

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board (Protocol # 2017-1135) and the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board.

Results

Interviews highlighted some of the barriers to accessing contraceptives currently experienced by women in this area, and showcased how this FQHC is adapting their approach and their services to better meet patient needs. The following themes emerged.

Lack of knowledge of services offered

There is still a noted lack of knowledge about available services on the part of many community members. It seems to be a combination of not knowing the exact services that this FQHC offers, a general sense of shyness about accessing services, along with a lack of knowledge about what services are available to them and at what cost.

Several patients stated that services are not promoted well in the community, that women need to know ‘where to get services along with, like, being taught what the services will do for them’. Another patient stated that many community members ‘don’t know of this place’.

In addition, both providers and patients reported that many community members do not seem to know what services are available to them, and what services are covered by certain programs. One of the family nurse practitioners described it this way:

Once they come in, we typically talk to them about like the women's health program that we offer to get them free stuff, especially long-term birth control. So, I just think a lot of it is just more lack of education within the community … because they just don't know what they can get or what they can't get and how much it's going to cost, which is a big fear in the population that we take care of.

This lack of knowledge about the services being offered is partially due to the lack of advertising about services. According to several board members, one of the reasons behind the lack of advertising about the provision of birth control services is due to the perceived sensitive nature of the topic. One board member states that this FQHC needs to ‘let a broader audience know about the services’ and ‘if people don’t know of the service, they’re not going to use it’.

Lack of knowledge about birth control and reproductive health

One fundamental barrier to accessing services might simply be a lack of understanding about reproduction and birth control methods.

The interviews focused in part on the lack of general knowledge that people in the region had about birth control, reproduction, and sex. From a clinic perspective, providers perceive this lack of knowledge when women patients present and are screened for unmet birth control need and are subsequently counseled on different options. Several of the providers mentioned the fact that some of the patients they see have minimal contraceptive knowledge. For those with contraceptive knowledge, it’s not always accurate.

When asked what was one of the biggest barriers to women accessing family planning services in the region, the executive director mentioned a lack of education as one of the biggest issues:

It always seems like well, health education, right, kind of rises to the top. One of those things that the community feels is lacking across the board for everyone in the community. I think sliced out of that though, what you tend to see also is a lack of education around women's services and family planning I think. So, I think that's, this topic is absolutely something that the community hones [sic] in on. And you know we have a lot of rural communities [in the region] specifically … I think that, I think the people there really do see it as a need and patient education is lacking. So, I think that's something that we are trying more so ourselves to focus on …’

When asked if women knew about all the types of birth control available, several of the patients responded that they didn’t think many women did or, if they did, they might have incorrect information.

Misinformation and misconceptions

There is also erroneous information when it comes to birth control methods and reproduction – both how contraceptive methods work, and general reproductive health. One of the women interviewed stated that she would have liked to have more sexual health education: ‘I guess a little bit more, maybe about just sex in general because there's a lot of like sort of misconceptions there’.

One patient spoke of the potential detrimental role of inadequate information or rumors that can be harmful if medication is not taken as prescribed:

So, um, but I think when you're sort of a young person, you get all of these rumors from your friends and uh, there is a story about this girl that lived in a college dorm and she was like, I'm gonna go have sex, let me borrow your pills. And it's like you can't just take one and it works. So there's even like that sort of misconception like, you know, uh, how long do you need to be on it before you can be sexually active.

Several of the women interviewed still erroneously believed that there was no contraceptive option that would work for them: ‘I just personally, it doesn't work well with me so I don't take it, but it's nice to be able to have the option if I wanted to’.

Education on birth control

One possible reason for the lack of information/misinformation on birth control methods is that, in schools, many women in the area hear a message of abstinence, and therefore do not come to the clinic for preventative services. This is seen as one of the biggest barriers to women accessing services. Even though they might want the services, the stigma associated with accessing those services might be too much, and they may end up with an unwanted pregnancy. As one provider states:

People aren't preventing us from providing services but in places where women need to hear about contraception they are hearing abstinence. And that may as well be considered a barrier, because if they hear abstinence, they're not going to come to the clinic seeking birth control, even though in their minds they want that and, and in their hearts they want that, but they're being fed this, this line that abstinence is the only way to go.

Another provider echoed this statement by stating that sexual health education in local schools needs to go beyond abstinence-only education:

And I think education, people just need more education about, you know, sexual health, sexuality, all of those things, you know, abstinence is not the way to go in my opinion, because kids are going to have sex and so give them what they need to prevent the pregnancies and STIs [sexually transmitted infections] and all those things. So, I think education is kind of lacking in our area.

Some sexual health education is happening in schools but, according to one patient, the education started happening after kids were already experimenting with sex: ‘I feel like it might be too late, whenever they provide education’. One of the providers complained that even though some schools teach kids about contraceptives, they don’t teach them about where or how they can access them, which is an important component of teaching comprehensive sexual health education.

When asked where they first learned about birth control, the women had differing answers, but the common theme was that they did not remember much about what they learned, even though for some of them it was not that long ago. None of them had received comprehensive sexual health education, although most of them had received some sort of basic education on contraceptive methods available.

One woman stated that she first learned about sexual health at church. Two women stated that they first learned about sexual health from their mother, one stated that she first learned about sex from her peers, and three first learned about sexual health at school.

For those who learned about it at school, some thought that the knowledge they were given was adequate, and others wished that they had learned more in depth about each method in particular. When asked if they would have liked to learn more about sexual health at school, several of the women responded that yes, they would have like to receive more detailed information about both contraceptive methods and about sex.

Most of the women spoke of learning about birth control methods, but none of them reported learning about sex, consent, and healthy relationships. When one patient was asked if she remembered being taught about different methods in school, she answered, ‘No, it was more of just saying no and not having sex instead of more teaching you what to do in case you do have sex’. Another patient thought that her school had done a good job at teaching them prevention: ‘I feel like it was more always prevention, like ... they were like this could happen if you have sex. It wasn't like this is going to happen’. Increasing access to information may lead women to make ‘informed choices’, which according to one patient is what is needed.

Care model

In an effort to better address the needs of the community, this FQHC’s primary care providers systematically assess reproductive intention for all women in primary care and provide contraceptive counseling to those women who need it. All of the primary care providers interviewed conducted comprehensive patient education at the clinic as part of offering integrated contraceptive services. Education is offered to all women of childbearing age. Although many primary care providers in other healthcare settings do offer contraceptives, the level of patient education offered at this FQHC was above and beyond what other primary care providers offered. For each initial visit, extra time is allocated to ensure a thorough conversation can occur. One of the things that differentiates them from others is the level of screening and education they offer:

We put more effort into taking the time with the woman to really thoroughly educate her, and then allow her to take home materials – written materials, and then come back and talk about it again. And that's, that part of it is what I understand is not that common for a family practice doctor to do.

One of the providers explains the process and the reasoning behind providing comprehensive contraceptive counseling:

I think we provide pretty good education for all of the patients here because I mean, I go into depth about this stuff – they are very aware of what they're getting themselves into before they do it and, we're pretty open about making sure that we provide that for all of our patients. I think is very well implemented in this office in particular.

Most of the providers interviewed used some sort of tiered approach while providing patient education, which is recommended in the Quality Family Planning Guidelines. One of the providers uses a modified version of the tiered approach: ‘I present, you know, the methods, probably in the order that I think would be most beneficial to the given patient’. Another provider uses a more standard tiered approach, starting with the most effective methods:

I have a handout that has all of the different forms of birth control, the pros and cons and you know what might be best for them, so we had to go over each of those on that little handout that also shows them the efficacy of that.

All of the providers consider the particular patient’s situation as they discuss contraceptive options with her – if it is difficult for the patient to access the clinic, or if they have a forgetful patient, they might recommend a LARC so the patient does not have to come back to the clinic or remember to take a pill every day. According to staff members interviewed, there are several important cultural reasons why providing education at the clinic is so important. The low-income rural nature of this FQHC’s patient population makes it slightly more difficult, yet more important, to offer patient education. One nurse stated:

Um, I mean, you know, our area’s very rural, very under-educated, so there's not a lot of understanding as to why you need contraceptives, no matter whether it's a depo [Depo Provera] shot or something, someone may get a depo shot and think that it will prevent an STI [sexually transmitted infection]. It's just a lot of, you have to do a lot of education with our patients, which is good for us as well because it keeps it fresh in our minds.

One of the main goals of the providers is to alleviate fears and misconceptions that patients might have about different types of methods.

All of the patients interviewed confirmed receiving education while at the clinic and being given options about the type of birth control that would best suit their needs. As one patient stated, ‘She went down the list and she said that I believe that will be the best option for you’. Although some patients receive a method at the end of their initial visit, patients are also offered the time to go home and reflect on the options they were given and take time to decide. The clinic manager explained the process:

And not always is a decision made at the end of that visit. They're given all the information they need, their questions are answered, but then they can call us back and let the nurse know that now I have decided on this. And if they have any questions, additional questions are answered and then we can go forward with whatever is needed.

A full range of contraceptive services are available at the clinic or through a prescription program with a local pharmacy. For devices such as intrauterine devices or Nexplanon®, a follow-up visit for insertion is scheduled, as most of the time these need to be ordered when they are not in stock. There is a protocol for ordering devices that all nurses follow. Same-day services for LARCs are rare and only offered on certain conditions, such as if a patient cannot come back for another visit due to extenuating circumstances such as lack of transportation. The clinic protocol states that LARCs should be inserted during the patient’s menstrual cycle and after one negative urine pregnancy test. In addition, providers like the patient to have time to review the information given to them during contraceptive counseling, so that they can make an informed choice – for many of them, this initial conversation might be the first time that they have been explained how LARCs work. They are given oral and written information while at the clinic, and given time to weigh the pros and cons of each method after the conversation with their provider.

Prescriptions for birth control pills or other hormonal methods, and condoms, can be given on the day of the initial visit. These can be given to women who are considering a LARC, to avoid an unintended pregnancy in the meantime. When asked who is responsible for providing contraceptive services to women, one nurse’s answer explained the overall philosophy of the health center:

Everyone. Because we don't, I mean we don't have anybody that is not providing women's healthcare in these, any of these offices.

The clinic manager described the main philosophy of the health center’s providers, which offers integrated services in family, dental and mental health:

Having that whole person integrated mindset that tells them I can't just treat this part of the person, their head or their diabetes or something. I need to treat the whole person, which includes women's healthcare, family planning, dental, behavioral health, it all needs to be treated and they have a wonderful mindset about being integrated with that.

Primary care providers wishing to replicate a model similar to that of this FQHC could start by researching One Key Question9 and similar pregnancy intention models to determine how best to serve their client populations.

Discussion

Research has shown that a low knowledge of services on the part of community members has been a barrier to people receiving birth control services at FHQCs nationally in the USA17. According to respondents, many people in the region covered by this FQHC do not seem to know what services are available to them, including the services that this FQHC offers.

Due to a lack of sexual health education, patients and some community members have a lack of knowledge about birth control and reproductive health in general. This lack of knowledge leads to women not knowing about their birth control options, or not seeking them out. One of the biggest issues in the region is a lack of focus on comprehensive sexual health education in schools, with a focus on abstinence-only sexual health education. Research shows that teaching abstinence-only does not work to prevent unintended pregnancy20. In addition, teaching abstinence-only sexual health education creates a negative stigma around sex, deterring women from accessing needed birth control methods.

The conservative culture in Southwest Virginia contributes to the lack of comprehensive sexual health education in schools, and increases stigma around sex. Because of this, sexual health decisions are made based on misinformation and fear instead of informed by evidence.

In the region, and in the USA in general, there is still erroneous information about birth control and reproduction. This is due in part to the stigma still associated with sex and sexual health, and the lack of comprehensive sexual health education taught in public schools. Rumors and incorrect information are widely shared when the correct knowledge is not present. A lack of education can lead to misconceptions, which may exacerbate fear and mistrust.

Barriers to integration from the community and patient perspectives were numerous, and many of them are due to deeply held beliefs. The role of culture cannot be underestimated in a small, tight-knit, rural, conservative community, and this context must be considered while providing services to local patients.

Conservatism and stigma associated with discussing sexual health were indicated as barriers to people accessing services. Stigma can play a big role in preventing access to services. If people do not feel comfortable discussing sex, or if there is a stigma attached to having sex outside of marriage (as is taught through an abstinence-only curriculum), patients will be less likely to seek birth control methods and be more at risk for an unintended pregnancy. Stigma limits educational opportunities being offered, therefore limiting people’s knowledge about services and birth control methods.

Not knowing about how a birth control method works, or the potential side effects, may lead to fear about using it, or mistrust in it. Being educated about a specific method leads to higher adoption of that method.

In a rural community, in the USA and in other countries, trust is important; not only trust in a birth control method, but trust in the provider administering or recommending it. One of the benefits of offering integrated services is that a patient can already have an established trusting relationship with a primary care provider, and seek a birth control method from them without having to establish a relationship with a new provider, in effect eliminating a potential barrier to care. Offering integrated services can prove valuable to women both in the USA and internationally.

Fear and mistrust in birth control methods may be due to patients not having accurate information about methods, and making erroneous decisions based on poor information. By educating women, teens and young adults about birth control methods, misconceptions and fear may be diminished, leading to an increase in contraceptive uptake.

Conclusion

This FQHC has adapted to their surrounding culture by ensuring that every woman seeking primary care at the center is screened for contraceptive need, offered contraceptive counseling and comprehensive contraceptive methods. This includes taking the time to educate women and answer questions, and giving them time to reflect on options. This FQHC’s integration of contraceptive services is a model that can be replicated by other FQHCs, by local health departments, and by private physicians, both in rural parts of the USA and in rural areas elsewhere. This FQHC may consider further ensuring access to LARC by offering same-day LARC insertion to all clients to further decrease contraceptive barriers in this rural area.