full article:

Dear Editor

As of 1 May 2020, more than 3.4 million cases of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections and more than 240 000 deaths due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) had been reported worldwide1,2.

In Germany, about 85% of COVID-19 patients are cared for mostly by family physicians in community practices, which allows hospitals to concentrate on critically ill patients. In order to ensure regular operations of primary care practices in Freudenstadt, and due to the limited supply of protective gear during the pandemic, one practice in the region was selected to diagnose and treat all suspected and/or confirmed COVID-19 cases.

This district in the Black Forest, in south-western Germany, comprises 870 km2 with a population of 117 935 citizens. Patient care is provided via 98 primary care practitioners (family physicians, general internist and pediatricians) based in four small cities and 12 municipalities. One acute care hospital with 10 intensive care beds is located in the district. Here, we report and clinically characterize the first cohort of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients in this rural district.

Beginning with the first case reported on 4 March, until 24 April 2020, the district observed a period prevalence ratio of 442.6 PCR-confirmed cases/100 000 inhabitants to the national health authorities3. Thus, during the study period, Freudenstadt was considered one of the areas most severely affected by SARS-CoV-2 infections in Germany.

Between 4 March and 24 March, a total of 829 patients with a suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection were sent to this practice by primary care physician for oropharyngeal, real-time RT-PCR testing4. A total of 102 (12.3%) patients tested positive. According to national guidelines, 100 of these patients went into quarantine at home, and two required hospitalization. Of the 100 patients who quarantined at home, 91 (91%) agreed to an extended follow-up period by this specialized COVID-19 practice for infection-related symptoms.

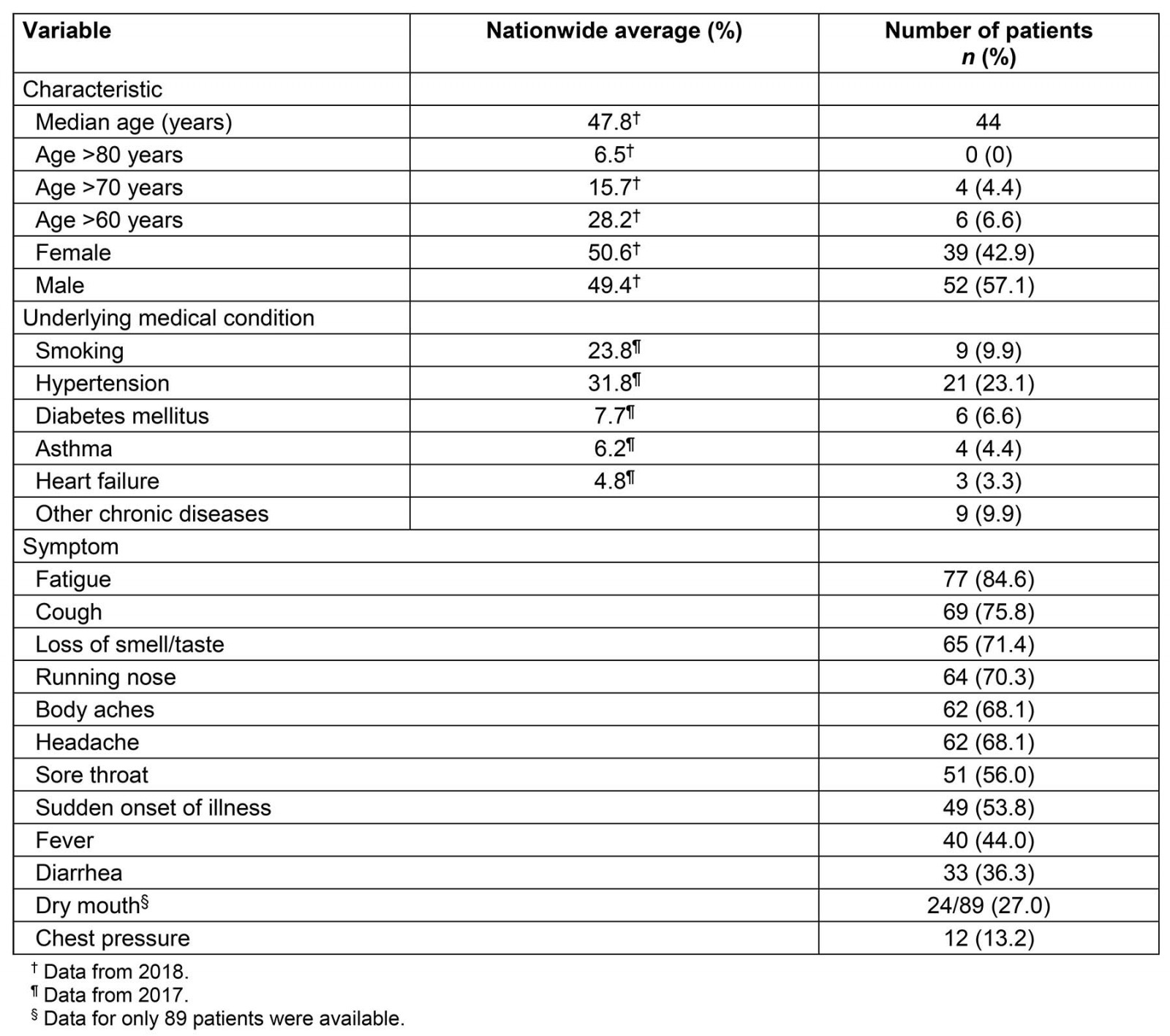

Corresponding to the national average, the most common risk factor among these 91 patients (median age 44.0 years, 57.1% male) was arterial hypertension, followed by diabetes mellitus, bronchial asthma and chronic heart failure (Table 1). The most common presenting symptoms were fatigue (84.6%), cough (75.8%), and loss of smell and taste (71.4%).

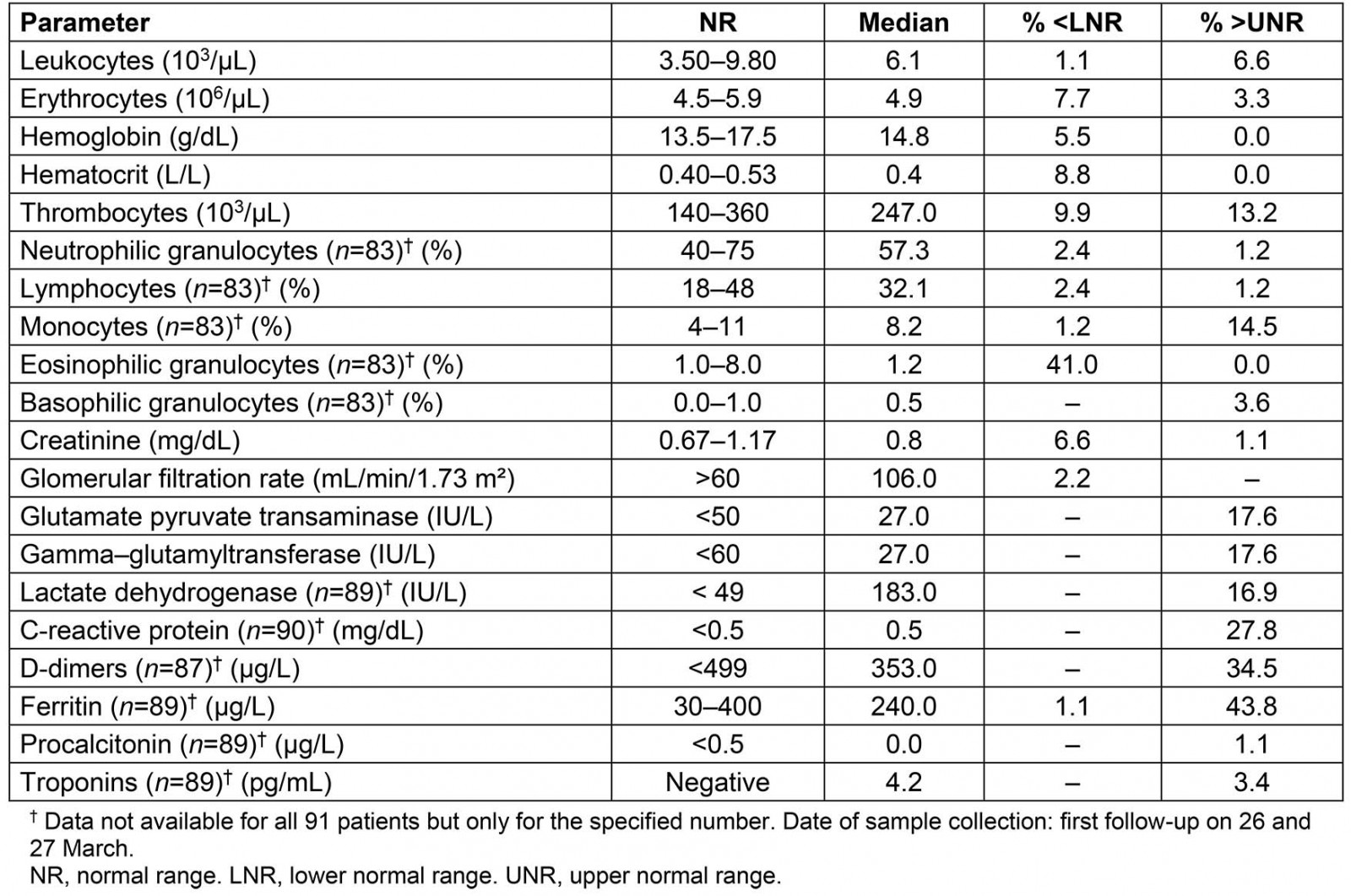

As shown in Table 2, 43.8% of the subjects had elevated ferritin levels and 41.0% had low levels of eosinophil granulocytes. C-reactive protein, D-dimers and LDH-levels were within normal range, reflecting the mild course of disease.

Between 5 March and 24 April, none of these patients required hospital admission, and no deaths were reported. Elderly patients, often cared for in retirement homes by family physicians, are underrepresented in our sample.

Our cohort represents the first 91 COVID-19 patients from one of the districts most affected by the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in rural Germany. The exclusive management of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 by specialized community practices could be an effective approach to treatment, as long as the clinical course of these patients remains mild.

Table 1: Characteristics of the patient cohort, and nationwide averages5-10

Table 2: Laboratory findings for patient cohort

WCG von Meißner and PG Blickle, Hausärzte am Spritzenhaus, Family Practice, Baiersbronn, Germany

C Strumann and J Steinhäuser, Institute of Family Medicine, University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck, Germany

MM Kochen, Institute of Family Medicine, University of Freiburg, Germany

B Wölk, LADR Zentrallabor Dr. Kramer & Kollegen, Geesthacht, Germany; Institute of Virology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany

J Pömsl, Family Medicine Centre, Kaufering, Germany

W Fink, Ärzte vorOrt – MEDI-MVZ GmbH, Ambulatory Health Care Center, Stuttgart, Germany

references:

You might also be interested in:

2009 - The challenges and rewards of rural family practice in New Brunswick, Canada: lessons for retention

2008 - The future, our rural populations and climate change - a special issue of Rural and Remote Health