Introduction

Aboriginal peoples of Australia have a strong connection to their traditional lands, with land, holding both spiritual and cultural importance – so much so that they may forfeit medical treatment to return to their traditional land, also referred to as ‘on country’1. Australia is a vast island continent and, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census, 473 356 people lived in remote and very remote Australia at that time. Of these, 119 595 identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander2. Living in remote and very remote Australia comes with many challenges, such as geographical isolation, lack of or varying reliability or availability of infrastructure, and variable/intermittent essential services such as telecommunications, electricity supply, access to fresh food, employment opportunities and financial security3. Other complications are retaining a stable health workforce, and health staff having insufficient skills when participating in Aboriginal Australians passing away. The term ‘passing away’ is preferred to ‘dying’ within the Aboriginal population to avoid upsetting someone with the news of a death on their traditional lands. In addition, a lack of understanding of Aboriginal cultural practices has contributed to the current inadequate delivery of end-of-life care4,5.

Review of the literature

In remote and very remote Australia, remote area nurses are usually the only ones available to help coordinate the care of Aboriginal people with a terminal condition who want to pass away on their traditional lands. The literature frequently criticised effective end-of-life services on many levels for its poor service delivery to remote and very remote Australia1,3,4,6,7. Although the literature discussed the importance of the cultural significance of Aboriginal Australians passing away on their traditional lands, it discussed little on what remote area nurses felt. This included their skill level in participating in end-of-life care for Aboriginal people dying on country, and whether the health service they had experience with was able to cope with the situation. There was also a dearth of information around remote area nurses' perceptions of the cultural significance of end-of-life care for those passing away on country. For example, Willis (2019) was critical of the lack of support relating to palliative care services in remote and very remote Australia for Aboriginal peoples7. However, this was not discussed from the perspective of a remote area nurse, but from the point of view of service provision7.

McGrath and Phillips (2008) suggested that some cultural practices are becoming devoid of their original significance when people are not passing on their traditional lands8. An example is smoking ceremonies in Northern Territory communities, performed to drive away the deceased spirit; if the ceremonies are not performed, it is thought that the spirit cannot take its place in the afterlife, and it can be trapped between death and future life. McGrath believes a recent shift in this cultural practice is a result of Aboriginal people typically passing away far from their traditional lands8. Hales and Edmonds (2018) discusses the cultural significance of someone passing away on their traditional lands and stressed this as being particularly important9. Nevertheless, people are evacuated from their homelands to city hospitals, where the health services are located, and end up dying far from their cultural lands1. This has been described as ethnocentric behaviour within the health system9.

After an extensive search of numerous databases, no literature was found that looked directly at the opinions and thoughts of remote area nurses concerning the barriers and enablers for Aboriginal people passing away on their traditional lands. However, the literature that was found criticised the lack of support available in remote and very remote Australia to Aboriginal people with terminal conditions passing away on their traditional lands. Different reasons were given for this, ranging from staffing issues to geographical and logistical complications, as well as a lack of understanding of cultural practices3,8-10.

Aim of the study

The research question in this study was ‘What are the enablers and barriers perceived by remote area nurses to assisting in end-of-life care to Aboriginal Australians on their traditional lands?’ As it rests mainly with remote area nurses to support end-of-life to patients, their family, and the communities within which they work, this research was conducted to gain remote area nurses’ perceptions.

Methods

The study was conducted in February to July 2020. A literature search was conducted using the following databases: ProQuest, Ovid Medline, Cochrane Library, Sage Journals, Wiley Online Library, Elsevier and ScienceDirect. Key words were ‘Aboriginal', ‘Australian’, ‘Dying’, ‘Remote Area Nurse’, ‘Traditional Lands’and ‘End-of-life Care’. A short questionnaire was developed based on questions that arose from the literature review, such as Aboriginal people passing away on country and whether remote area nurses grasp this significance. Because all authors have spent many years working remotely, some of the questions were based on personal experience.

Questions relating to support by health services were derived from experiences working within the health services and published articles about Aboriginal people dying on country. Qualtrics was used as an electronic survey distribution and collection platform. The survey was open for 3 weeks. A letter of introduction and explanation about the research was distributed, and a link to the online survey. Participants were a convenience sample recruited by emails sent (with permission from the university) to students enrolled at the Centre for Remote Health, Flinders University. An invitation to participate in the questionnaire was also published with CRANAplus11. CRANAplus is a not-for-profit membership organisation for remote area nursing in Australia. It provides education support and professional services to the remote health workforce.

Development of questions

The questions were designed to gain insight into remote area nurses' perceptions about Aboriginal people with a terminal diagnosis passing away on traditional lands. The questionnaire comprised four sections: demographic questions, two series of Likert scale questions, and five open-ended questions inviting respondents to express how they felt about Aboriginal people with a terminal condition passing away on their traditional lands. Two series of Likert scale questions asked remote area nurses to respond to statements (1 (‘strongly agree’), through to 5 (‘strongly disagree’)) about the skills they felt they used to deal with particular situations and the capacity of health services to deal with the situations12.

In the first series of Likert scale questions, remote area nurses were asked to rate their perceptions on the following statements:

- It is important for Aboriginal people in my community to die on country (own opinion).

- Many Aboriginal people in the community I currently work would choose to die on country if they could.

- It is possible for Aboriginal people in my community who have a terminal diagnosis to die in the community.

- I feel confident in supporting Aboriginal people to die on country.

- Most RANs I have worked with have sufficient knowledge and skills to support Aboriginal people who wish to die on country.

The second series of statements dealt with the provision of support provided by health services:

- Generally supports Aboriginal people dying on country.

- Has sufficient medical equipment to enable Aboriginal people in my community to die on country if they choose.

- Has sufficient staff to enable Aboriginal people in my community to die on country if they choose.

- Are able to access palliative care support services.

- Have a person that is available to give cultural and spiritual advice and support.

Responses to the open-ended questions in the questionnaire were analysed using thematic analysis13.

Analysis

As part of thematic analysis14, the primary researcher used colour coding to categorise patterns within the data and identify categories and themes. An independent thematic analysis expert also analysed the data. The findings were similar, enabling words to be allocated to identify the categories and themes.

Inclusion criteria

For inclusion to participate in this study, the respondent must have been a registered nurse who had worked in remote or very remote Australia and identified either as a remote area nurse or was defined as such in their contract of employment. They must have been either currently or previously employed as a remote area nurse.

Exclusion criteria

Excluded from the study were registered nurses who had not been employed as remote area nurses according to their employment contract, registered nurses employed in metropolitan or regional Australia and registered nurses who did not identify as remote area nurses.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was gained from Flinders Social and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee (approval number 8618).

Results

Demographics

There were 26 responses to the questionnaire. A total of 14 people completed the questionnaire, and 12 were excluded because they had not fully completed it. Of the respondents, 13 were female and one was male. The average time working as a registered nurse was 15 years. Eleven respondents were currently employed as remote area nurses, and three had previously been remote area nurses. The average time working as a remote area nurse was 4.8 years. At the time, eight respondents were working in primary health and five within the hospital system. One declined to answer this question. Five had postgraduate qualifications ranging from postgraduate certificate to master's level. Two were currently obtaining postgraduate qualifications, and seven stated they had no postgraduate qualifications.

Survey results

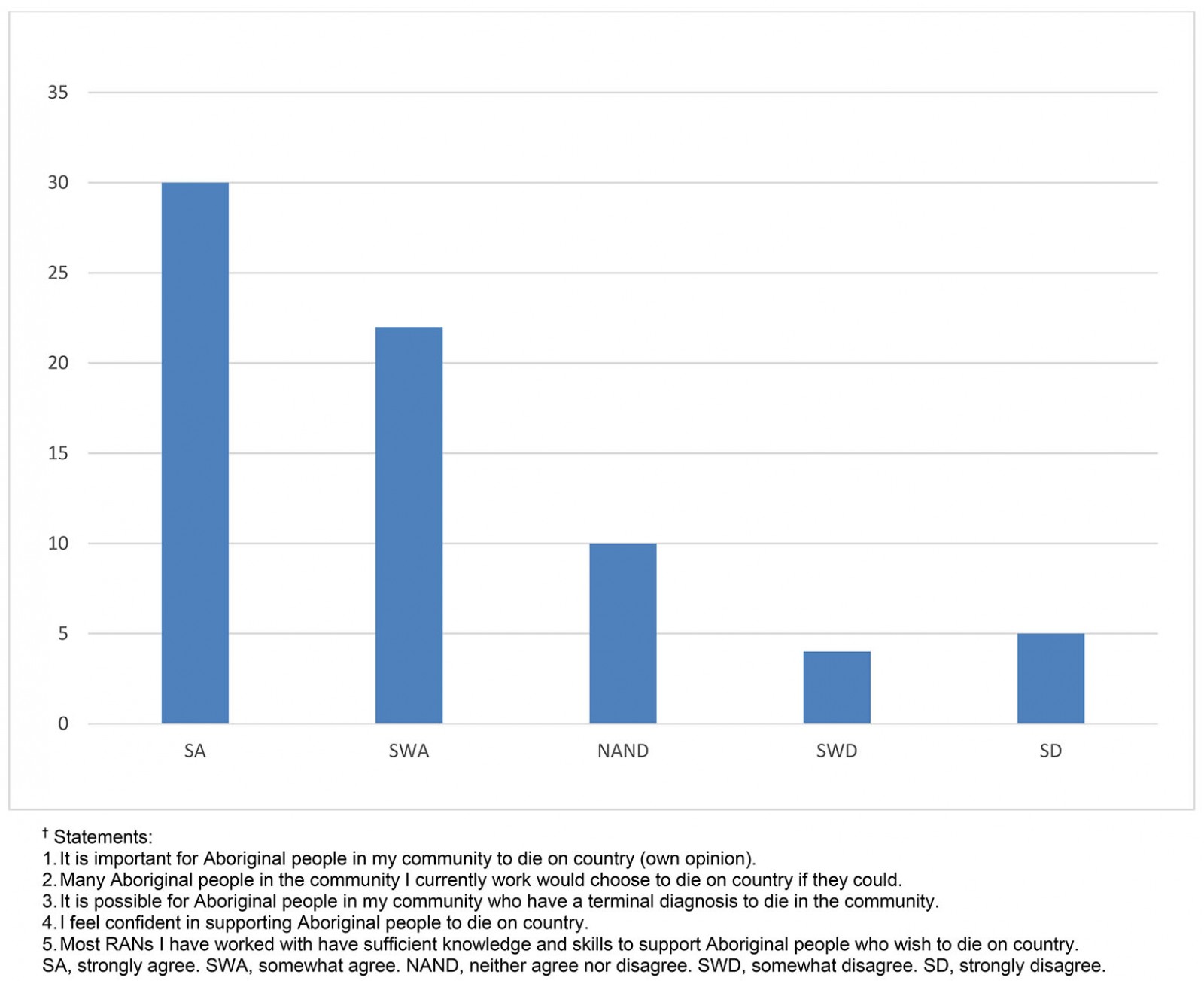

Figure 1 shows the overall responses to the first series of statements, about the skills remote area nurses felt they used to deal with particular situations relating to Aboriginal people dying on country.

The connection to country is significant as it holds both cultural and spiritual beliefs, values and social constructs that set down the rules for living. These are passed down from generation to generation through ceremonies1,7. It can be concluded that from the first five questions that remote area nurses are aware of the importance of having a person pass where they choose. They also perceived that they had the skills to participate in this process.

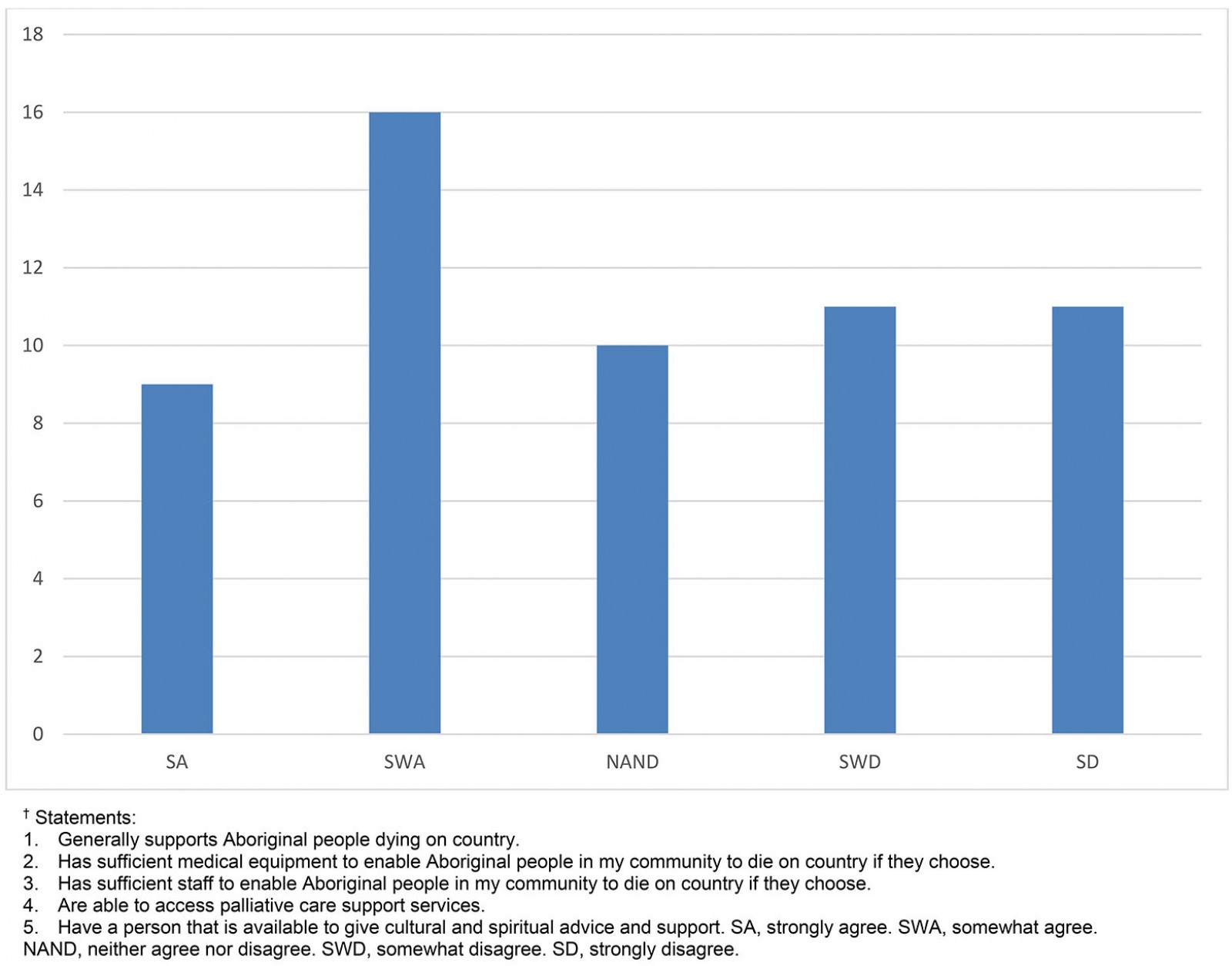

Figure 2 shows overall responses to the second series of statements, related to provision of support provided by the health service. Several factors need to be considered by health services providing support, such as geographic location, equipment, and consultation with family and community, as the level of skills can be challenging concerning the necessary support.

Figure 1: Overall responses to statements† about skills remote area nurses felt they used in relation to Aboriginal people dying on country.

Figure 1: Overall responses to statements† about skills remote area nurses felt they used in relation to Aboriginal people dying on country.

Figure 2: Overall responses to statements† related to provision of support provided by their health services.

Figure 2: Overall responses to statements† related to provision of support provided by their health services.

Thematic analysis

The five open-ended questions aimed to determine how remote area nurses felt about different aspects of Aboriginal people with a terminal condition passing away on traditional lands. Thematic analysis was undertaken on the data by the primary researcher with an independent thematic analysis expert. The main categories identified were Culture, education, resources and communication.

Culture

Within the category of Culture, the themes developed were cultural awareness, education and family support.

Cultural awareness: Several respondents indicated that cultural awareness is generally lacking for caregivers or health-related matters. For example, respondent 3 commented that there was ‘definitely need [for] more cultural awareness training’.

Education: Respondent 5 noted that ‘general education re cultural importance of dying on country’ is needed, and respondent 7 stated ‘I would have liked some education regarding culture and mores of the Aborigines’. Based on the feedback from the respondents, there is a perceived lack of education around culturally appropriate end-of-life care and a perceived need for cultural awareness education.

Family support: Respondents felt a lack of family support, with respondent 4 commenting ‘lack of support from family, carers that are ineffectual’. Respondent 5 said ‘supporting people to die on their country is difficult when there is no family support’. Respondent 9 looked at it from another viewpoint, which may explain the lack of family support, as they stated: ‘… pressure from family. Family fear of payback and blame’. Based on respondents' feedback, remote area nurses perceived was a lack of guidance and support from family when a family member passes away on their traditional lands.

Education

There was a lack of education around Culture and a need for education around the delivery of culturally appropriate palliative care. Respondent 3 said they need more ‘palliative care training – this goes for GPs too’. Respondent 6 also made a comment about ‘further training of staff’. Respondent 8 felt that the promotion of end-of-life care was possible along with ‘education of nursing staff. More promotion that this is possible’. It was also felt that more education is needed on delivering culturally appropriate palliative care.

Resources

Within the category of resources were the themes of staffing and equipment.

Staffing: The lack of staffing in remote areas was a concern. Respondent 1 said there was ‘not enough staff in remote clinics to provide support through palliative care due to their already high workload’. Respondent 6 felt that there was also a lack of staff: ‘care needs can be remarkably high in palliative care, it is difficult to manage existing clinic demands and ensure adequate dignified care to someone in the last stages of palliation depending on their condition’. Respondent 5 looked at it from another angle, stating a need for ‘staff willing to take it on and support it’. The results suggest that the lack of a stable workforce hinders the ability to provide end-of-life care within the community, so too the willingness to support end-of-life care when it comes to passing away on traditional lands.

Equipment: There was a perceived lack of equipment, lack of access to equipment and lack of knowledge about how to use equipment in end-of-life care. Respondent 14 said ‘access to a 'grasby' or similar pump was limited’. Respondent 1 wanted to know ‘how to use and make up syringe drivers, what drugs are the best to use for each symptom, e.g., pain, nausea, anxiety’. Respondent 3 felt that ‘a fridge or morgue would make logistics easier in the case of a death overnight’. These responses show that, from a staffing perspective, providing end-of-life care in remote or very remote Australia can be challenging. There is a lack of staffing and access to equipment to aid in the delivery of end-of-life care.

Communication

The data showed that communication between the health service, staff family, and community are vital enablers. Respondent 3 felt that ‘when the clinic has a good relationship with the community, the people feel able to ask knowing the clinic will do what it can to assist’. Respondent 8 also felt this, saying ‘communication – ensuring shared understanding’ were enablers. In addition, the relationship between the health service and the community came through as necessary, with respondent 9 saying they believed an enabler was the ‘relationship between the clinic, community and family. The ability to involve cultural brokers staff that are flexible’. Another nurse commented that ‘if the clinic wants to, the clinic can do’. Communication between the health service and family/community is an essential factor in enabling end-of-life care delivery by remote area nurses in remote and very remote Australia.

Thematic results summary

There was a clear need for more cultural awareness education regarding end-of-life care. Respondents also felt there was a need for more family guidance. Respondents also felt that they lacked knowledge in the delivery of palliative care. In terms of resources, staffing and equipment seemed to be the primary concerns. Respondents felt that they needed more staff to handle the extra workload that would be created with a person passing away in the community. There was also a concern that there was a lack of access to equipment and how to use it. Finally, respondents felt that communication between the health service, including staff and the family/community, was important when it came to delivering culturally safe end-of-life care.

Discussion

There were 26 responses to the survey, of which only 14 could be included for analysis. This sample size cannot fully represent the entire remote area nursing workforce; however, it indicates how remote area nurses perceive barriers and enablers to an Aboriginal person with a terminal diagnosis passing away on their traditional land. Most respondents agreed with the statements relating to Aboriginal people passing away on their traditional lands and their importance to the people. They also felt they had enough knowledge to be able to participate in this practice. However, most respondents did not feel that the health service could manage end-of-life care for Aboriginal people in remote areas.

Culture, education, support, and communication were the four themes identified in thematic analysis. These are all important factors for a person wishing to pass away on their traditional lands. The disparity in health between non-Indigenous and Indigenous populations has been attributed to lack of cultural awareness and lack of understanding of cultural practices and norms outside of one's own cultural experience. This is not surprising because most undergraduate nursing programs in Australia up until 2005 had limited if any cultural awareness built into curricula15,16. Culture encompasses many different concepts17. Passing away on traditional land seems to be becoming more prevalent as the move towards more ethical healthcare delivery occurs. This is being overseen by bodies such as the National Health and Medical Research Council18. Research undertaken by Shahid et al (2013)19 studied 15 palliative care providers who had a lack of cultural understanding of their Aboriginal patients. The study did not identify if the palliative care providers lacked cultural understanding of other cultural consumer groups19.

Communication has been both an enabler and barrier, with non-Indigenous and Indigenous people not understanding the other party's perspective13,19-21. Since Australia has been colonised, there have been disastrous consequences for cultural practices, such as banning talking in one's language or removing children from their families22. A combination of events has led to the current situation in which different perspectives between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people result in unequal health care, with a significant disparity in the health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians18,23-25. There has also been a shift in health care, with government bodies established to monitor and regulate care delivery24. Other research identified that communication and a willingness to change enabled some of these barriers to be overcome26. There has been a poor understanding on both sides as to what is available in relations to end-of-life care10.

Limitations of the research

Time was a constraint in this study because the research formed part of the requirements for a master's degree and had to comply with set completion dates.

The survey sample was small, giving only a snapshot of what remote area nurses perceived as barriers and enablers to having an Aboriginal Australian pass away on their traditional lands.

Cultural identity was not included in demographic questions because the study aim was to capture perceptions of remote area nurses. Therefore, it is unknown if any Indigenous Australian remote area nurses participated in the survey or how many nurses from other cultural backgrounds participated. This could have a potential bias to the responses to the statements and questions asked.

Based on the results of this research, further, rigorous research is required into remote area nurses’ perceptions on barriers and enablers to having an Aboriginal Australian pass away on their traditional lands. Most importantly, research examining the perceptions of Aboriginal Australians is also needed.

Conclusion

This research was undertaken and written during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, the methods used enabled respondents and researchers to continue with the project. The information gathered from the survey and the analysis of the data gave some insight into remote area nurses' perceptions of the enablers and barriers around having an Aboriginal person with a terminal diagnosis pass away on their traditional lands. A high percentage of remote area nurses understood the importance of enabling a person to pass away on their traditional lands. Regarding perceptions of the healthcare service, there a high percentage of remote areas nurses said they could still provide end-of-life care, but the barriers to this can be challenging to overcome.

As part of the thematic analysis remote area nurses felt they needed more education around culturally appropriate end-of-life care and more cultural awareness education. They also believed there was a need for more family support. Providing end-of-life care is not helped by a constantly changing workforce, inadequate infrastructure and limited access to equipment and support.

This research shows that communication and acknowledgement of each party’s requirements, needs, wants, expectations and limitations, and brainstorming both formally and informally about these needs, could lead to fewer barriers. Overall, it seems that when those involved from the community and the remote area nurses came together, they were able to deliver what they considered a successful service to patients, families, communities and themselves, enabling end-of-life care to occur on traditional homelands. Unfortunately, this does not happen often and is not always enabled by the healthcare provider.

This research confirms that, while there remain limitations in providing end-of-life care to Indigenous peoples on their homelands, remote area nurses can be very resourceful and try extremely hard to overcome those limitations. The research shows remote area nurses have the will to provide this care, and, with more support from the care providers, this may happen more frequently and with more ease.

References

You might also be interested in:

2005 - Recruiting undergraduates to rural practice: what the students can tell us