Introduction

Telehealth has many advantages for delivering health care to rural and remote Australians. It can be used to deliver numerous health services including burn rehabilitation, which provides similar advantages to in-person rehabilitation, for example reduced acute and follow-up patient transfers, inpatient bed days and associated costs1,2. Telehealth also reduces the need for clinicians and/or patients to travel long distances to attend face-to-face appointments2,3. The accuracy of burns reviews using telehealth has been demonstrated to be similar to that of face-to-face consultation4 suggesting telehealth for the follow-up of burns patients is both effective and efficient. Despite the advantages of telehealth for burns review, there is little research investigating patients’ perceptions of telehealth services.

The Occupational Therapy (OT)-Led Paediatric Burn Telehealth Review (OTPB) Clinic runs telehealth reviews for rural and remote burns patients. The OTPB Clinic was developed at Townsville University Hospital in northern Queensland, Australia, to improve burn rehabilitation services for rural and remote patients5. It has been operational since January 2017 and has successfully increased the frequency of clinical review and reduced demand on paediatric surgeon outpatient appointments, suggesting a benefit for the health service5. The OTPB Clinic’s catchment covers a large area of northern Queensland and has a broad demographic, including Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. Therefore, it is prudent to obtain patient’s perspectives of the service to ensure the benefits also accrue to patients.

Evaluation of health services typically measures quantitative outcomes. For example, occasions of service and cost are quantifiable measures used to determine the efficiency and/or effectiveness of a healthcare service. However, these measures do not account for patient and families’ perceptions, their experience of a service or its impact on their everyday lives6. Qualitative data can provide rich descriptions and insights of the healthcare service from the perspective of the people who use the service, enabling the service to be fit for purpose. Individuals interpret their experience within the context of their everyday life and are influenced by the situations, events and people around them7. Therefore, it is timely to qualitatively investigate telehealth to ensure it is meeting the needs of patients as well as the health service.

The aim of this research was to explore the experience of the OTPB Clinic from the perspective of rural and remote patients’ families and clinicians. The research objectives were to:

- explore the experiences of rural residents in relation to their child’s burn injury and the issues associated with rehabilitation

- investigate the perceptions of patients’ families/carers of the OTPB Clinic

- ascertain the experience of clinicians in selected northern Queensland public health facilities of working with rural patients who have had a burn injury and their perception of the OTPB Clinic.

Methods

Design

Interpretive, or hermeneutic, phenomenology was used to understand, interpret and give insight into the lived world of patient’s families and clinicians and their experience of the OTPB Clinic8,9. Interpretive phenomenology acknowledges a researcher’s prior knowledge, noting the difficulty to bracket or remove themselves from interpretation of the data. The researcher works towards an understanding of the phenomenon by interpreting the lived experience described by participants8.

Recruitment

Participants were purposively identified from the 35 families who had been seen in the OTPB Clinic by the principal investigator. Participants were from a range of rural and remote geographical areas (including all health service districts) and cultural backgrounds. Participants were parents or caregivers of children accessing the OTPB Clinic at the time of recruitment, or who had recently been discharged from the service. Clinicians in rural and remote areas who had participated in at least one OTPB Clinic telehealth review were also invited for interview. All participants were contacted by the research coordinator, who was not involved with clinical care delivery, to explain the study and gain consent.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the research coordinator by either phone or telehealth. Interview guides were developed by the research team and reflected key areas of interest. Interviews with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants were conducted in the form of a yarn with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander investigator from the research team to promote culturally sensitive data collection.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were offered to review their interviews by either transcript, audio-recording or reading back over the phone. Following confirmation of the transcripts, all data were de-identified. The research coordinator took notes following each interview, which were referred to during data analysis.

Data analysis

Research team members repeatedly read the interview transcripts to empathise and understand the participants’ descriptions of their world9. Significant quotes and sentences that provided an understanding of how the participants experienced the OTPB Clinic were highlighted8. These statements were then developed into ‘clusters of meaning’ or themes8. All four authors met several times to achieve consensus on the themes. The researchers named the themes and phrases in their own words to capture the lived world of participants. Researchers continually returned to the transcripts to discuss the data, and to review and modify themes and subthemes9.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was received from Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/17/QTHS/221) and Far North Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/17/QCH/128-1189) prior to research commencement. Governance approval was given for the five health service districts in which data collection occurred. The Townsville Hospital and Health Service Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Leadership Advisory Council gave approval and provided recommendations on the conduct of the research.

Results

Participants and themes

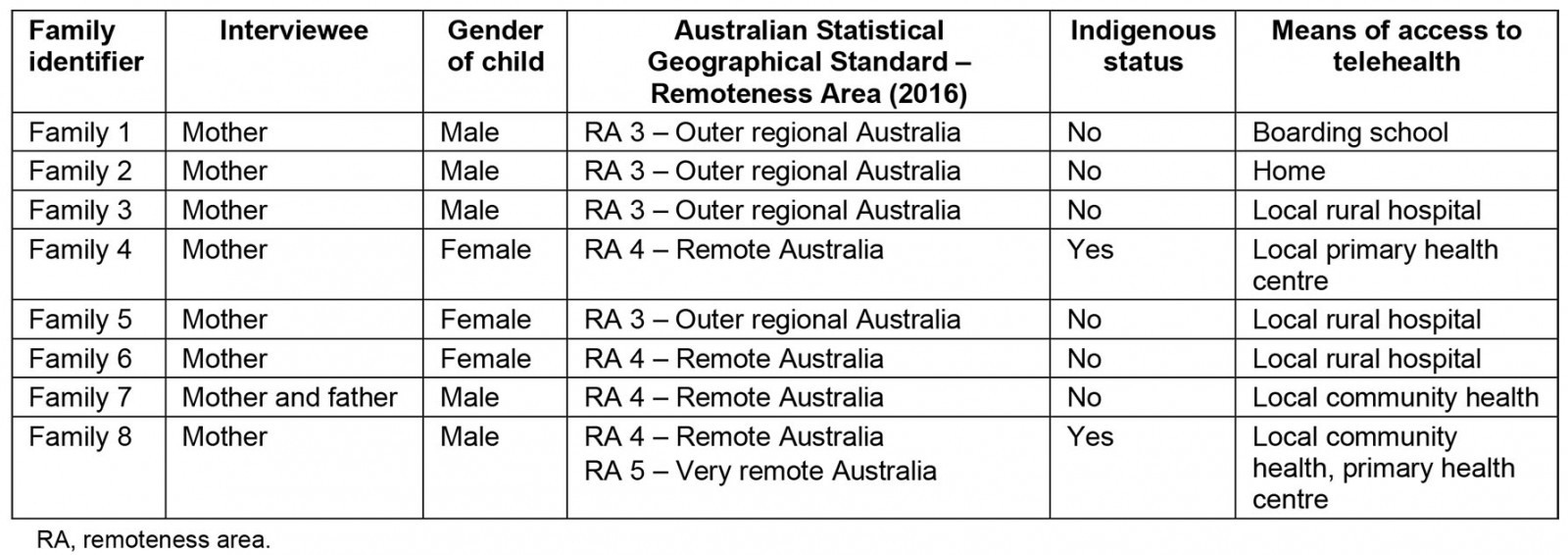

Eight families consented to participate in this study (Table 1). Children of participating families ranged in age from 7 months to 14 years at the time of their burn injury and lived in outer regional, remote and very remote communities10. Two families identifying as Aboriginal consented to participate in the study. Mostly, the mother of each child took part in the interview. Those families who received their telehealth consultations at the local rural hospital were supported by an OT. For families who attended a health centre, a nurse attended their consultation.

Six clinicians working in public health facilities in rural and remote Australia (as classified by the Australian Statistical Geographical Standard – Remoteness Area (RA) (2016)) and who participated in the OTPB Clinic reviews consented to interview. Four clinicians were OTs working in outer regional (RA 3; three OTs) or remote (RA 4; one OT) Australia and two clinicians were clinical nurses in remote (RA 4) or very remote (RA 5) Australia.

Four major themes were derived from the thematic analysis of manuscripts: continuity of care, family-centred care, technology and rural capacity building. These themes and subthemes are discussed below.

Table 1: Demographic information for study participants

Continuity of care: Continuity of care from a child’s hospitalisation to rehabilitation was stated as a positive aspect of the OTPB Clinic. The continuity of care gave the families confidence in the service because of the consistency of provider, which developed into trust over time. These positive attributes were reinforced by rural clinicians’ observations of the families obtaining the telehealth service.

… the mother knew her [the clinician] straight away. It was good for her to see a familiar face, not just someone different all the time … up here too, we lack the continuity of care because we do have a high turnover of nursing staff because it’s a bit too remote. (clinical nurse 1, RA 4)

Confidence in the expert advice Families stated they had confidence in the service because the OT demonstrated expert skills required to monitor their child.

… they all seem to have dealt a lot with burns and so there wasn’t any wondering what they should do, they just seemed to know exactly what they were doing. (family 1)

Rural clinicians reiterated the families’ perception of confidence in the knowledge of the OTPB Clinic therapist to treat a child’s burn as well as support them in their local clinical role.

Having that extra support and guidance … is very helpful and any sort of questions that … as a therapist that you might not know, you’ve got that support and backing from another senior specialist clinician there to answer that as well… I feel it sort of leaves the family feeling quite confident that they are receiving as good as care that they can be receiving at that point in time. (OT 3, RA 3)

Consistency and trust Families valued the consistency of seeing the same OT throughout their rehabilitation treatment. The consistency of OTPB Clinic therapist was an important aspect to the service, which allowed a good relationship to develop.

… knowing the same person’s going to be there all the time too. So, they’ve known [child] from the day that she burnt herself. So that’s a positive thing for her as well because, you know … she doesn’t want 10 different people looking at her … she’s formed a relationship with them … you feel like you can be open and honest. (family 6)

Clinicians stated that the connection of the OTPB Clinic with the hospital where the acute care and surgery were performed was a positive. This connection would allow the OT to re-engage the surgeon if required.

… that’s quite positive for a lot of families … they’ve got a connection towards the site that’s actually done the operation … if something does go wrong. It’s not anything that’s too hard to be able to get back in contact with the surgical team either if there’s any issues with scarring … (OT 3, RA 3)

The OTPB Clinic was seen to largely foster continuity of care and trust, but some participants expressed confusion regarding the roles of the local clinician and the OTPB Clinic therapist.

… I didn’t want to overstep the mark by going straight to [OTPB Clinic] because [local therapist] was our first base so I sort of went through them but I probably should of [sic] went straight to [OTPB Clinic therapist]. (family 6)

Similarly, one clinician discussed hesitancy regarding their exact role in the consultation.

I wasn’t sure exactly what I was going to be required to do leading in. (OT 1, RA 3)

Family-centred care: The whole family benefited from the OTPB Clinic. Participants discussed the positive impact on the family’s wellbeing because their care was provided close to home, alleviating the burdens of child care and travel. Communication was improved with clear, simple instructions for the family, and the OTs were responsive to families’ questions.

Communication Most families felt their OTPB Clinic therapist explained things well and gave clear instructions. They valued the responsiveness to questions and inclusion of parents in decision making.

… they dumbed it down for me which was good. They didn’t exclude me, like [local therapist] would ask me questions as well as [treating therapist] so I was included into the conversation and whatever, if I didn’t understand or needed clarification then [treating therapist], you know she was there clarifying anything that I needed to know. (family 3)

One mother from an Indigenous background described the language as ‘too much’ and reported she would have liked more simplified communication. She felt the presence of an Indigenous Health Liaison Officer during the appointment would help.

… she was using big words … couldn’t really understand what she was talking about half of the time. Yeah, like she could have … at least break it down a bit. (family 8)

A mother spoke of the benefits of the communication with her family when her son accessed the OTPB Clinic from boarding school.

He understood what he needed to do and the feedback to me was great because again, I wasn’t left in the dark worrying about [child’s] burn, if it was going to heal, if he was doing the right thing because he would tell me what he was told and I was told so I knew of the full circle there. (family 1)

Family wellbeing The OTPB Clinic’s focus on wellbeing included ‘not just the physical’ but also emotional impact on the child.

… because being a 8 year old boy he was very worried how he would look in the glove going to school and things like that. So, she was really good in helping him and even myself to deal with that. She even offered to jump in on a teleconference and speak to his class if need be so that was brilliant. (family 2)

Reduced travel had a positive impact on families, with some describing 8-hour drives previously to attend appointments at Townsville University Hospital. The long drives were exhausting, implying telehealth from home or ‘up the road’ was convenient and easier.

You’re at home in five minutes, you’re not taking 2 and a half hours to get home. So, it’s just a lot easier. I’m not the biggest fan of driving long distances on my own, so yeah … it’s just more comfortable. (family 5)

Clinicians highlighted challenges with travel and transport out of local remote communities. Telehealth was considered a good solution to the challenge of limited transport schedules, particularly during the wet season.

And also, with up here in the [local area] with the weather and that, it’s not always [possible] to get off the island [Horn Island] as per any planned itinerary. (clinical nurse 2, RA 5)

Financial benefits were mentioned by families in regard to accessing telehealth from their local communities.

… obviously running a car down there and back, there’s the cost involved in doing that. There’s the cost involved in car parking and all of those things when you get down there. There’s financial costs in the fact that you have to take time off work to go down there. So you’ve got all those costs, like even though the services at the hospital aren’t costing us, there’s all those overheads and things that cost to actually travel down to the hospital and by actually having the telehealth, we avoid all of that. (family 2)

Furthermore, the OTPB Clinic reduced interruption to daily family life. There was no need to take time off work or school, to organise school transport or extra care for other children, thus reducing the burden on the family.

We have four small kids … and my husband works away in the mines … so while he’s away, I’m transporting these four little kids around, with [child] to … you know, get her foot looked at and things like that. (family 4)

The opportunity for both parents to attend the telehealth appointments and be involved in their child’s rehabilitation was highly valued.

… we’ve got the… farm, so [child’s father] can’t leave here very often. So the telehealth conference was great in the fact that he could come over to the house, he could participate in the conference for say, half an hour or so, and he can be involved in knowing what’s happening and he really, really does enjoy and get a lot out of being part of that. (family 2)

Some of the telehealth clinic appointment times were not always convenient for participants and were noted to still cause disruption to daily life.

… they’ve only been able to do um, I think Thursdays. Which is no good for me because my daughter goes to school on those days so I would have to go, drop her off at 9 o’clock, pick her up at 10, take her to the appointment until like 11.30 or 12 o’clock and then pick her up again at you know, 2.30. (family 6)

Technology: Numerous aspects of technology pertaining to the OTPB Clinic were discussed. For example, the quality of the telehealth connection, familiarity with using the technology and requirement for training, and the opportunity to have both audio and visual cues were all discussed as important aspects of technology and clinic delivery.

Connection quality Both positive and negative experiences regarding the quality of the connection during the telehealth consultation were discussed by families.

I couldn’t hear … it was a bit crackly and I couldn’t hear you guys properly. (family 8)

Telecommunication services and internet connection outside of Queensland Health facilities in rural and remote areas was identified as suboptimal.

… our internet isn’t wonderful here and it’s still not … our connection dropped out, it just wasn’t great … that’s not a telehealth issue, that’s an issue that we have with our telecommunications provider. (family 2)

Some families spoke of their uncertainty about the image quality through telehealth. The use of still photographs was therefore considered by both families and clinicians to be a helpful strategy in providing accurate details and description of the child’s injury.

… I don’t know if youse could see his feet properly, that was my concern … like you’s not having a good look at his feet so youse can’t really tell if it’s healing or anything like that … because then after the teleconference the nurse, whoever the nurse was in the room with us, took a photo of his feet and sent it. (family 8)

Obviously over the teleconference she couldn’t see the scarring and the improvement as much … I suppose that’s why [local therapist] was there so [OTBC therapist] could refer back to him and ask him questions that maybe I didn’t fully understand or couldn’t fully answer for her. (family 5)

Use and training Families who used local public health facilities for their telehealth consultations voiced concerns about staff familiarity with using the telehealth equipment.

… they could turn it on and everything but the remote didn’t … I don’t know if they knew how to use the, operate the remote properly. At one stage there I had to get [child] to lay on the table and put her foot in the air just so the girls in Townsville could see it because of the way the camera was set up … I felt that at the time they probably just needed a bit more education on it really. (family 4)

Families that were exposed to the use of a Lightning to USB camera adaptor at the remote site spoke of the advantages of being able to use an additional camera.

… using that extra camera, to get you know right up close so they can actually see. It’s quite clear when they can see it. (family 7).

The benefits of a Lightning to USB camera adaptor were also highlighted by a clinician who had previous experience of using them clinically.

… trying those Lightning adaptors that connect to your phone, and so you can really get your camera up closer to the burn rather than some distance away. (OT 3, RA 3)

Access to and availability of telehealth equipment The variability of hardware and software necessary for telehealth consultations differed across the sites. The variation meant some rural sites experienced a shortage of telehealth equipment, rendering the service less than ideal, whereas others received increased equipment because of the OTPB Clinic.

… you have to book well in advance. And sometimes it can be a little challenging. (clinical nurse 1, RA 4)

… as a result of this project, and the increase in the use of telehealth … allied health has been able to get their own telehealth machine. (OT 4, RA 4)

‘Feel’ of telehealth Appointments through telehealth were perceived as personal. Visual contact and ability to observe the body language of the clinician gave a positive ‘feeling’ to the interaction during the consultation.

… it’s like having her in the room and just talking to her, you know, face to face … (family 4)

… because you can actually see… it’s not just a phone call, where you can’t see their expressions and 90% of communication is with what we do, with mannerisms, actions, behaviours so that’s the good thing about it. (clinical nurse 1, RA 4)

Rural capacity building and supervision: Paediatric burn rehabilitation is a small aspect of a wide variety of clinical tasks performed by clinicians in rural and remote communities. Rural allied health and nursing staff considered that the OTPB Clinic built their clinical capacity and suggested telehealth could be utilised for professional supervision.

Building clinical capacity Rural and remote OTs spoke of gaining new skills (eg garment measuring) and awareness of new resources and products (eg different types of silicone) through involvement with the OTPB Clinic. They also spoke of the increased confidence it gave them by reaffirming their existing knowledge in burn rehabilitation.

… we’ve gone from being a service that used to just do developmental paeds [paediatrics] to actually being an OT service that meets the needs of our community but also has some really good professional development things and areas of growth that’s enabled shared care which is so important … the isolation out here … there’s lots of risks associated with that … so that shared care is so important and that support, that openness and that flexibility that Townsville offers us I think has really created a really positive environment for shared care. (OT 4, RA 4)

Clinicians suggested the model used by the OTPB Clinic could enable shared care in other ways. It was suggested the telehealth model could be used to include other disciplines in the rehabilitation or provide support for other specialised OT services such as adult burns, hand therapy and lymphoedema. The telehealth model could also assist with supervision of early career graduates new to working in rural or isolated areas.

Not many are trained up in the area [lymphoedema]. I think there’s even room for that to be looked into for your hand therapy as well. Because that’s another really complicated field for therapists as well, especially if you’re a new grad[uate] and you’ve been given all these difficult cases. (OT 3, RA 3)

It helps me out because I’m getting essentially a 1 on 1 supervision with a clinical client with [therapist], so getting that extra support from her … allows me to provide better care in the future … It’s definitely beneficial, especially for me being out here being quite a junior therapist. (OT 1, RA 3)

Discussion

This study explored patient and clinician perspectives of the OTPB Clinic described previously. The OTPB Clinic was successful in increasing burn reviews for rural and remote paediatric patients and reducing travel time for families5. However, service delivery should meet the needs of the community it serves, so this study was developed to explore patient, family and rural clinician perspectives of the OTPB Clinic. Major themes emerging from this study are continuity of care, family-centred care, technology and rural capability building. Overall, the patient experience of the OTPB Clinic was positive.

The study broadens the understanding of the benefits of the advanced-scope OT. The first advantage was the continuity of care achieved by having the same expert OT treat a patient in hospital and conduct the rehabilitation after discharge. The involvement of the advanced-scope therapist ensured prompt follow-up, responsiveness to patient needs, coordination of care and collaboration between health providers, which is consistent with the literature11.

The second advantage was the rapport developed between patient and provider. The expert clinical experience of the advanced-scope OT and the local knowledge and rural experience of the rural clinician was communicated to the patient and family. Developing goals, clear guidelines and expectations formalises this relationship and promotes an ongoing relationship between therapist and patient12. Feedback regarding the clarity of role of the rural clinician in the OTPB Clinic in this study was mixed. Additional work to clarify the role of the OTPB Clinic clinician and rural clinician would be beneficial.

The third advantage of the advanced-scope OT was the ability to educate remote clinicians. Allied health professionals working in rural and remote areas manage large caseloads over a wide geographical area and diverse clinical specialities13. As appropriate for the community they serve, rural allied health professionals develop generalist skills to manage a range of clinical conditions including serious burn injuries14. The OTPB Clinic compensates for lack of specialist skills in rural areas while also educating and upskilling rural clinicians in the rehabilitation of burn injuries.

The OTPB Clinic delivers dual financial benefits to the health service. First, the substitution of an advanced-scope OT delivers the rehabilitation service at less cost than the traditional paediatric surgeon-led model. Second, families noted the telehealth service saves time and reduces travel with minimal disruption to family life. These results are consistent with existing literature demonstrating the benefits of telehealth use for paediatric burn follow-up1,15. This study supports family-centred care providing desirable outcomes for children and families16 and the desire by rural families to engage the broader family unit in consultations rather than a single caregiver.

The telehealth model of care developed for the OTPB Clinic is clearly successful5. Recent increased use of telehealth in Australia and internationally because of the COVID-19 pandemic masks the prior extensive use in rural and remote service delivery to increase access3,15,17. Despite the extensive use, concerns about connection quality and training remain. For example, several families raised concerns regarding the ability of the clinician to make adequate judgements due to image quality. Evidence supports using digital still photography in conjunction with telehealth consultation for burn rehabilitation and other clinical specialties18. The OTPB Clinic adopted both digital photography and telehealth within the clinic. This information suggests rural and remote patients may accept telehealth services for some health needs but prefer in-person support for health concerns for their children. Future studies into patient preferences regarding telehealth are needed to provide services that meet patient and family needs.

Clarification of concerns and provision of clear communication and instructions encouraged families’ participation in their children’s rehabilitation. This finding is supported by a qualitative study that explored parents’ views on adherence to treatment in paediatric burns injuries19. Parents in the study felt that having an increased knowledge of, and confidence in completing, the intervention facilitated adherence to scar management regimes prescribed by the therapist19.

Culture and cultural background influence communication preferences and styles, particularly when using telehealth technology20. An Indigenous participant within the present study stated their communication experience did not meet their expectations. As there is a high proportion of Indigenous Australians in northern Queensland, it is recommended an Aboriginal Health Worker be present during telehealth to improve communication21. However, presence of the health worker or liaison officer should be negotiated with the patient because not all Indigenous patients feel they require the support of a health worker during telehealth consultations20.

Enhanced clinical skill and knowledge in burn rehabilitation was an advantage stated by remote clinicians in this study. Shared care/collaborative models for rural and remote residents utilising telehealth have been documented in clinical specialty areas other than burns20. Shared care promotes collaboration between therapists with different skills to enable planned delivery and joint responsibility of patient care. This approach promotes professional development for the rural and remote clinician and also allows rural therapists with a wide scope of practice and generalist knowledge to provide important contextual information for the specialist clinician12,20,22.

Some families felt rural staff appeared to have inadequate knowledge in the use of the telehealth equipment. The benefits of telehealth for rural and remote patients suggests further training for rural clinicians is required to increase acceptance of telehealth for clinical consultations23. Training packages are available for staff to support successful telehealth consultations. However, these may not be routinely used by rural staff because support for telehealth is a small proportion of rural clinicians overall working day. In order to increase access to the training packages, links could be sent at the time of appointment booking. Tip sheets for clinicians may also facilitate successful telehealth consultation.

Study limitations

Only two out of the eight families interviewed identified as Indigenous, which is not reflective of the wider community that the OTPB Clinic serves. This was partially impacted upon by issues maintaining contact with local healthcare service providers in Indigenous communities. Therefore, it was not possible to fully capture family opinions regarding paediatric burn rehabilitation via telehealth in rural and remote areas. Rural and remote therapists, however, were able to raise points and share their experiences working alongside patients who identify as Indigenous. Overall, the research has identified issues surrounding service provision that are relevant to an Indigenous population. The inclusion of an Indigenous researcher is an important consideration for future research in this area and is recommended.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates families value receiving burn rehabilitation for their children close to home and consider telehealth suitable to deliver this service. Both families and clinicians have confidence in seeking expert advice from an advanced-scope OT, supporting the use of expanded scope allied health roles to provide telehealth services in lieu of a paediatric surgeon. Furthermore, rural clinicians who engaged with the OTPB Clinic improved their clinical capacity and individual skills. It was necessary to meet communication needs including clearly explaining the differing roles of the leading and supporting clinicians. Experience of Indigenous participants suggested that families who identify as Indigenous should be offered the support of an Indigenous Liaison Officer to support clinical communication in telehealth consultations. Finally, it was crucial that all involved parties had adequate training in technology.