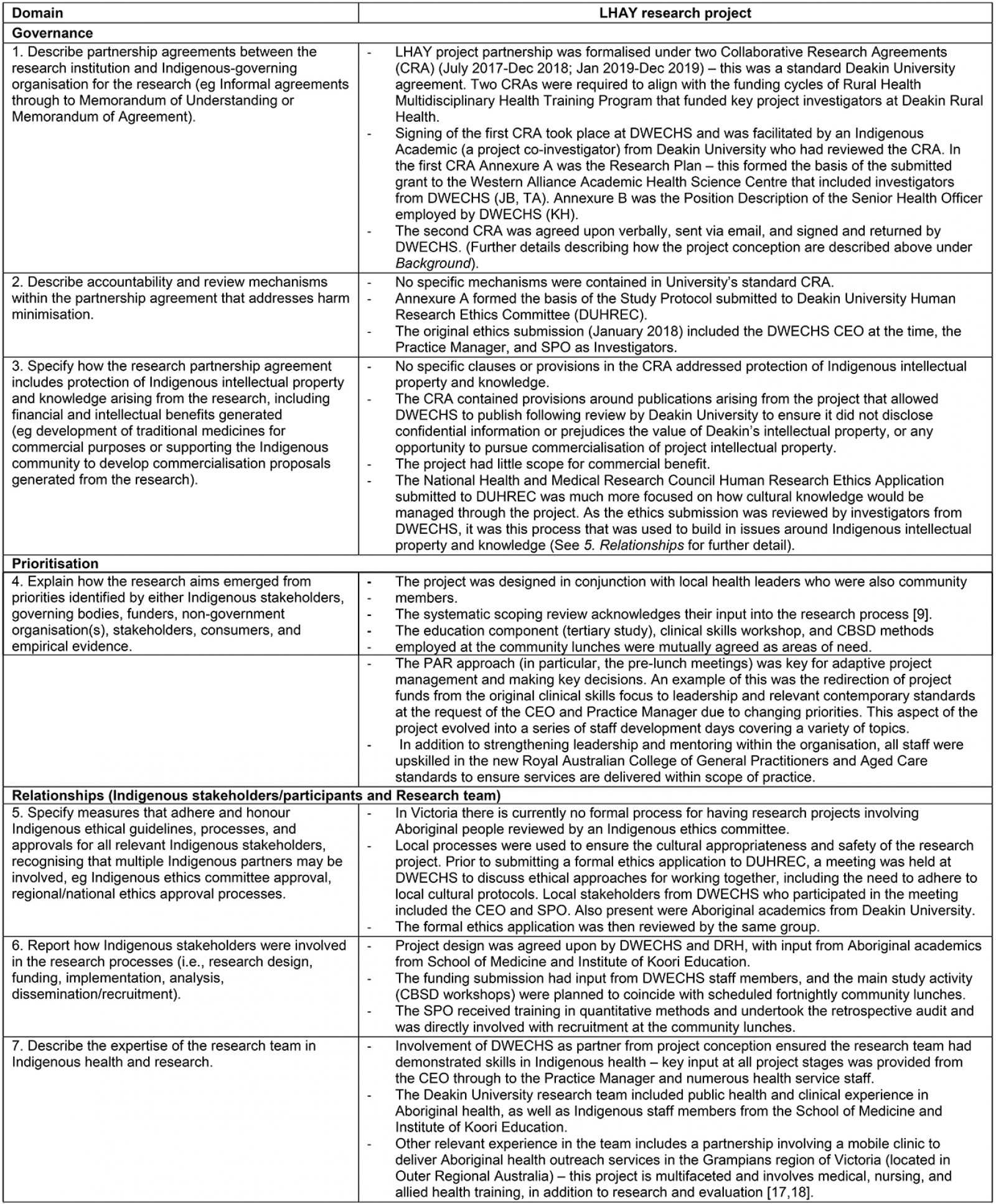

Context

In Australia, there are more than 140 Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) located geographically proximal to where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People reside1. Research evidence supports that ACCHOs are valued by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People for providing holistic and culturally safe primary health care2. Partnering with ACCHOs in research is appropriate for redressing health inequities experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, which includes a high burden of chronic disease3,4. Approximately 63% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People reside in geographical areas outside major cities; therefore, undertaking research in partnership with ACCHOs is important for improving the health of people living in these rural areas5.

Historically, some approaches to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research have been unethical, highlighting the need for culturally appropriate research methodologies (including Indigenous research methodologies) and ethical approaches to research conduct6,7. This includes a greater participation in the research process, improved accountability and transparency in reporting6,7. To meet the need for more culturally appropriate approaches to research, there has been a surge in the use of participatory research8,9, particularly participatory research using Indigenous research methods (eg yarning)10-12. As a research framework, participatory research involves a process of inquiry that aims to mitigate power imbalances by involving those affected by the phenomenon of interest, and has long been used to provide a voice for people otherwise excluded from the research process13. The inclusion of ‘action’ into participatory research (PAR) emphasises a goal-orientated objective of generating actionable outcomes14. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research, including Indigenous research methods such as yarning in PAR is understood to empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People to voice their perspective on complex health and social issues affecting their communities, and by doing so effect change10,12,15.

To address the need for greater accountability and transparency in reporting, the CONSolIDated critERia for strengthening the reporting of health research involving Indigenous peoples (CONSIDER statement) was developed16. As a synthesis of national and international statements and ethical guidelines for research involving Indigenous people, the CONSIDER statement provides a checklist of 17 items for researchers to report on16. The CONSIDER statement has recently been used to report on other research undertaken with Indigenous communities17 but has not been applied specifically in the rural health context or to participatory research or PAR projects.

‘Let’s have a yarn about chronic disease’: research project overview

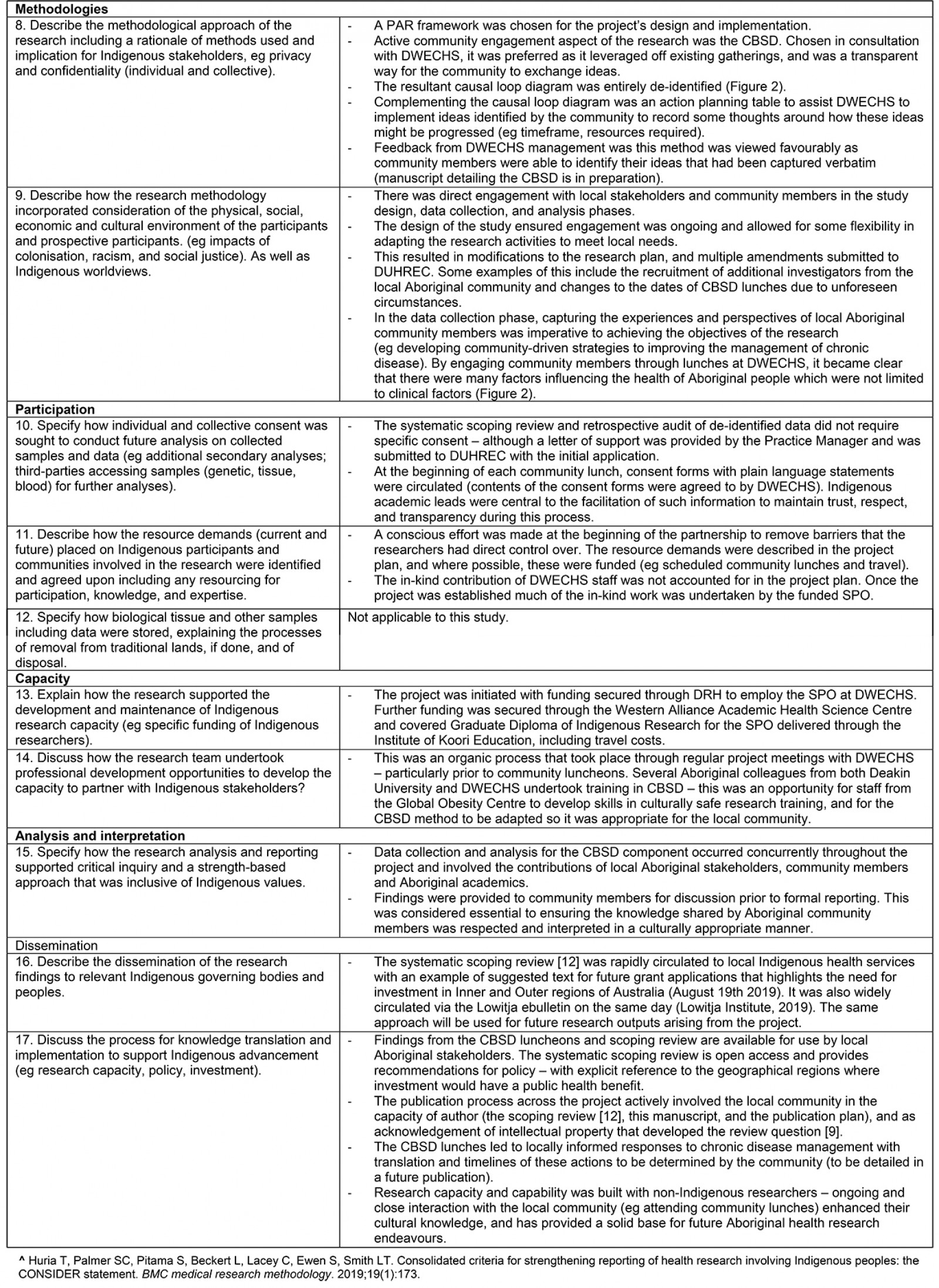

To respond to the burden of chronic disease in rural areas18 and high prevalence of chronic disease experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People19, Dhauwurd Wurrung Elderly and Community Health Service (DWECHS) and Deakin Rural Health (University Department of Rural Health (UDRH)), began conversations in 2016 about the management of chronic disease. As an ACCHO, DWECHS is located on Gunditjmara Country (Fig1) and was established by Elders to address the paucity of accessible health services for Aboriginal people in the region20. Gunditjmara Country is also home to the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, which is of special significance, and has attracted UNESCO World Heritage status21.

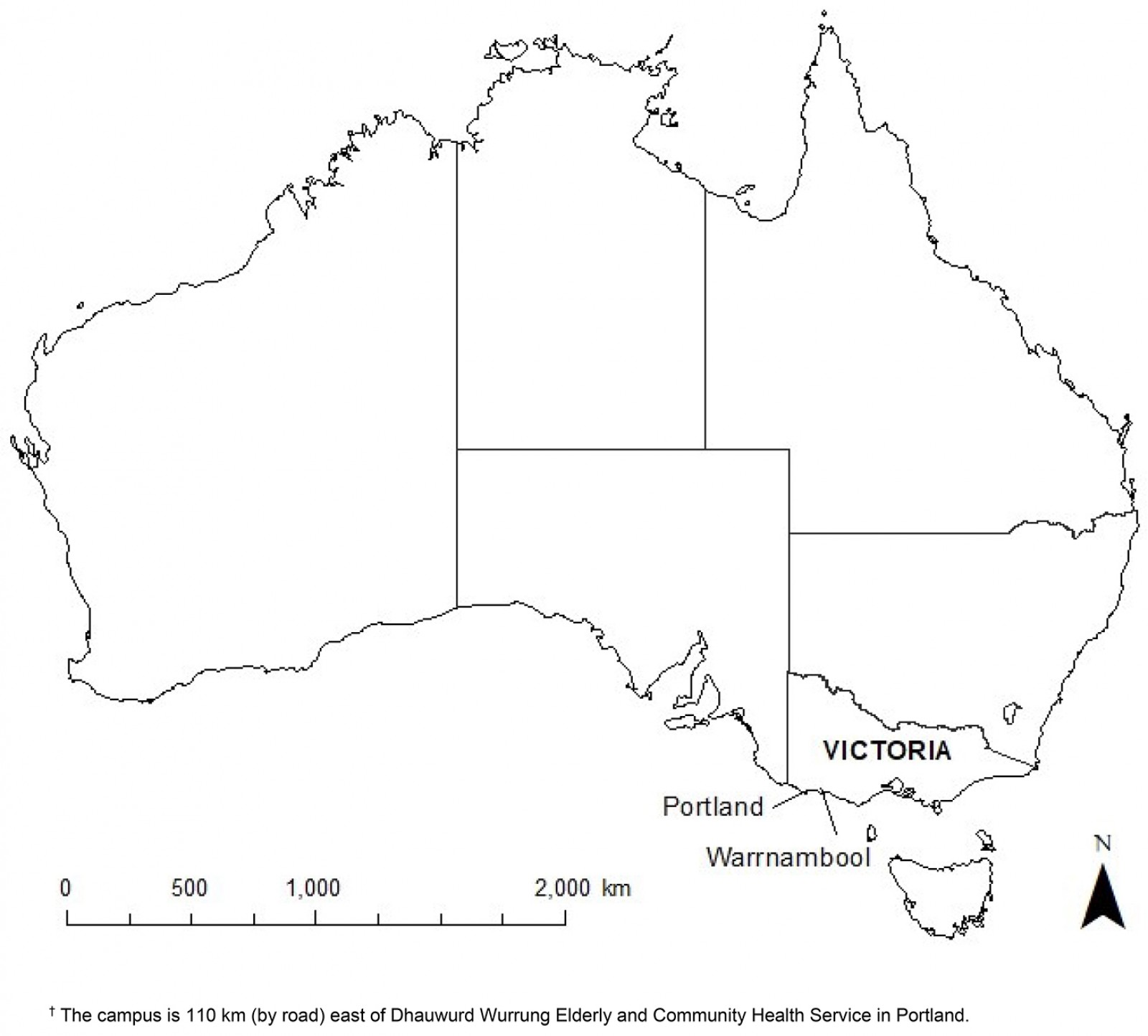

Early in the partnership, Deakin Rural Health secured external funding to employ a senior project officer to coordinate research activities focusing on chronic disease. This position was based at DWECHS and was filled by a local Gunditjmara community member with experience in the health sector. It was this position that was the catalyst for a PAR research project titled ‘Let’s have a yarn about chronic disease: a collaborative multidisciplinary participatory action research approach to addressing Aboriginal health in South West Victoria’ (LHAY). In late 2017, DWECHS and Deakin Rural Health, in collaboration with the Institute of Koori Education (since renamed National Indigenous Knowledges Education Research Innovation Institute), the Global Obesity Centre (a designated World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Obesity Prevention), and the Warrnambool Clinical School (a rural clinical school), were awarded funding for LHAY, which comprised four activities (Table 122-26).

This project report uses the CONSIDER statement to critically reflect participatory research undertaken in partnership with an ACCHO in the rural context and identifies lessons of value for future research. Critical reflection is an important process, particularly for non-Indigenous researchers learning how to partner with Indigenous communities to undertake culturally appropriate research27 and to improve on the ethical and scientific conduct of Indigenous health research internationally28. For transparency and accountability, reporting for the LHAY project against each criterion of the CONSIDER statement is also provided (Appendix I).

Figure 1: Location of Deakin University Warrnambool Campus, Portland, Victoria, Australia.†

Figure 1: Location of Deakin University Warrnambool Campus, Portland, Victoria, Australia.†

Table 1: ‘Let’s have a yarn’ research project activities22-26

Issue

By using the CONSIDER statement to critically reflect on the LHAY project, three issues were identified: importance of a research partnership, actively engaging Aboriginal community members in research, and building research capacity and capability.

Importance of a research partnership

Establishing a research partnership between local Aboriginal leaders from DWECHS, and researchers (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) from Deakin Rural Health and other Deakin University collaborating research groups, was the foundation for setting the research agenda and ways of working in the LHAY project. This partnership was embedded in the six core values (eg spirit and integrity, cultural continuity, equity, reciprocity, respect and responsibility) of importance to the ethical conduct of research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People6,7 – values not explicitly stated in the CONSIDER statement16. In practice, this was demonstrated by Deakin Rural Health and Deakin University researchers, including Indigenous academics, regularly meeting with DWECHS researchers (including Aboriginal community members, leaders and health professionals) through the entire research process (including prior institutional ethics submission), to discuss local ethical protocols, the needs of Aboriginal community members and expectations of the research (see Appendix I – Relationships). These meetings served as a platform for researcher accountability and learning, and also provided an opportunity to adapt the research plan and timelines as per a PAR framework.

The research partnership was formalised under two Collaborative Research Agreements (CRAs) (see Appendix I – Governance), which were also submitted to Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (DUHREC) as part of the institutional ethical approval process. A weakness of this CRA was that there were no specific accountability and review mechanisms described. Further, there were no clauses in this CRA specifically protecting Aboriginal intellectual property and knowledge, as recommended by the National Health and Medical Research Council ethical guidelines6,7. Rather, these issues were addressed in the DUHREC submission and through an ongoing authentic research relationship with DWECHS where issues were discussed and enacted on29. It should also be noted that in Victoria, there are no formal processes for having research projects reviewed by an Aboriginal ethics committee unlike in the neighbouring states of South Australia and New South Wales. In the LHAY research project, copies of the study protocol and all research documentation were provided to the DWECHS, who then provided a letter of support, which was attached to the DUHREC application.

Actively engaging Aboriginal community members in research

The research partnership was essential to informing the LHAY research aims, methodology and methods (see the Prioritisation, Relationships and Methodologies domains in Appendix I), which were based on the epistemological rationale that Aboriginal community members were the best people to participate and guide the research due to the knowledge they possessed30. Although many PAR projects undertaken in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People (and Indigenous peoples globally) are based on this epistemological rationale, the reporting of how participation occurred is often overlooked31. In the LHAY research project, Aboriginal community members and local stakeholders participated in all research activities (Table 1). To provide further illustration around the nature of this participation, the genesis of the systematic scoping review question arose in early discussions around geographical allocation of funding with local Aboriginal stakeholders who were concerned that Aboriginal people in inner regional and outer regional Australia received less funding than other geographical areas. The findings from the scoping review identified that, of included programs, 32.1% were implemented in major cities and 29.6% in very remote areas of Australia, with less in inner regional (12.3%), outer regional (18.5%) and remote areas (7.4%) of Australia23. Findings supported the need for a greater focus on chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people in inner regional and outer regional Australia23 and were rapidly disseminated to local Aboriginal stakeholders to support funding applications.

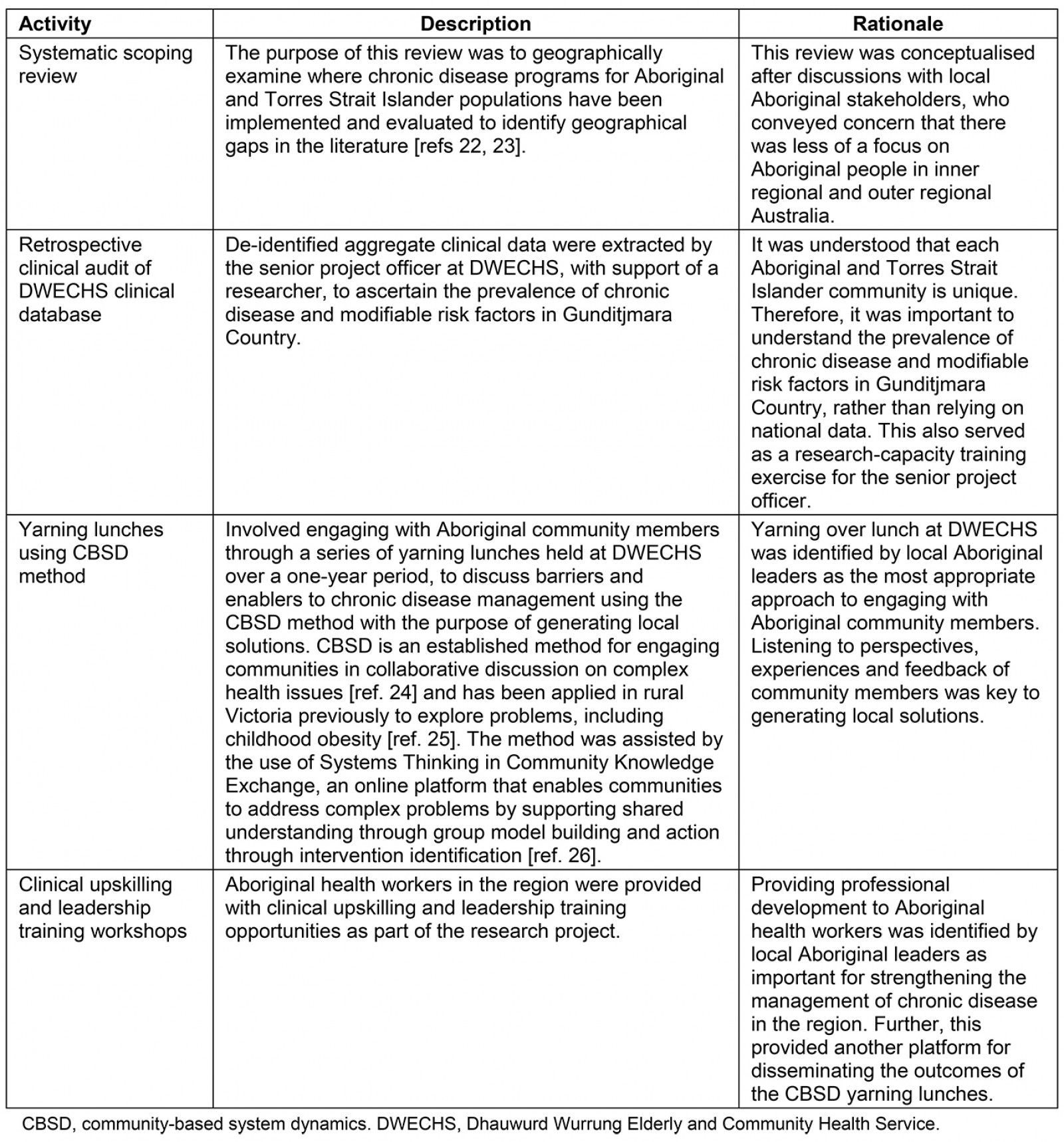

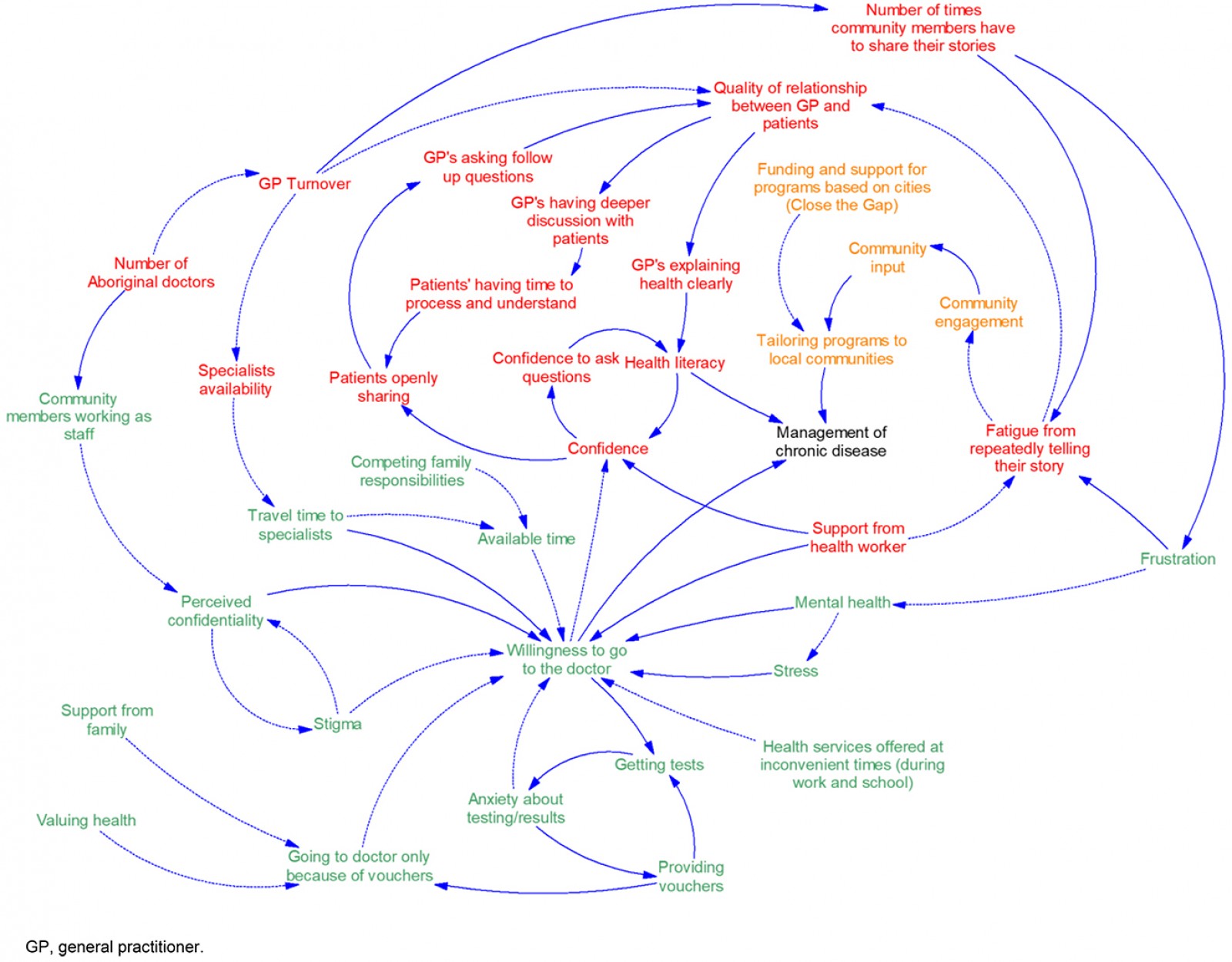

Similarly, the community-based system dynamics (CBSD) method was chosen for the strong alignment with participatory systems thinking approaches and PAR32, and because DWECHS and Deakin University researchers mutually agreed its application would transparently and interactively engage Aboriginal community members in self-determination (see the Methodologies and Participation domains in Appendix I). Numerous in-depth stories were captured directly from participating community members. These described the vicious cycles and sources of policy resistance that have historically perpetuated poor chronic disease management33. Owing to the setting within a specific health service, some of these stories related closely to local contexts; however, more broadly, the stories identified many common determinants of Aboriginal health. A strength of this approach was that the community collectively generated several actions in response to the local stories captured in the CBSD process. Actions also represent locally tailored responses to structural issues that affect Aboriginal people on a national scale (Fig2) (see the Analysis and interpretation and Dissemination domains in Appendix I).

Figure 2: Causal loop diagram developed over eight community lunches using community-based system dynamics methods at Dhauwurd Wurrung Elderly and Community Health Service.

Figure 2: Causal loop diagram developed over eight community lunches using community-based system dynamics methods at Dhauwurd Wurrung Elderly and Community Health Service.

Building research capacity and capability

Providing opportunities to build the research capacity and capability of DWECHS researchers were included in the LHAY research plan and factored into the research budget (see the Prioritisation and Capacity domains in Appendix I). This included providing research support and mentoring to the senior project officer (eg in undertaking the retrospective clinical audit at DWECHS and one-on-one training in quantitative methods), and delivering training to researchers, including DWECHS researchers and Deakin University researchers, to deliver the CBSD component and facilitate the yarning lunches (see the Methodologies domain in Appendix I). Funding was also allocated for other research training, including higher tertiary education (Graduate Diploma of Indigenous Research) and associated travel costs to attend training, to build the research capacity of the senior project officer. Although positive informal feedback was provided at the time, it would have been beneficial to obtain formal feedback from researchers to evaluate whether training improved research capacity and capability – an approach used in other research evaluating programs to build research capacity in ACCHOs34. Another strength of the LHAY research project, was that it provided an opportunity for Deakin Rural Health researchers and other Deakin University researchers to learn about ways of sharing knowledge, and gain skills in undertaking culturally appropriate research.

Ethics approval

A letter of support was provided from the DWECHS to support the ethics submission. Ethics approval was obtained through DUHREC (2018-009).

Lessons learned

Partnerships key to generating research of relevance

Each Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community in Australia is unique35. However, there are some lessons learned from the LHAY research project using the CONSIDER statement that are of value to future research and transferrable to other settings. For too long, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People have been involved in research without receiving any benefits, including participating in research and generating research evidence that is of relevance to them36. Although not explicitly mentioned in the CONSIDER statement, establishing a partnership based on trust and reciprocity was key to setting the research agenda and expectations from the research6,7. There is strong support in the research literature for taking the time to develop authentic partnerships and rapport with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, prior to writing research protocols and submitting for institutional ethical review29,37-40. Similarly, these ethical ways of working are also important when undertaking research within a PAR framework to mitigate power imbalances and to enable a free exchange of ideas between participants during the research process41,42.

The use of CBSD methods coupled with Indigenous research methods of yarning43, and training of local Aboriginal community members to facilitate sessions, were key strengths of the LHAY research project to empower the voice of Aboriginal community members and develop actions for local implementation44. Findings support the potential for CBSD methods to be a strong advocacy tool and research method for Aboriginal community members, bridging the needs for self-determination and greater participation of Aboriginal people in the research process8. Other research methods such as scoping reviews, can also be used as a tool to generate research of relevance to local Aboriginal stakeholders and ACCHOs, particularly when the research question is informed by community consultation22,23.

Although not a focus of the CONSIDER statement, sharing how Aboriginal participants and ACCHOs used or intend to use research findings, is also of value to understanding the relevance of research undertaken and possible benefits36. For example, the LHAY research project also yielded research evidence of immediate use to DWECHS in forming an organisational Statement of Intent as part of Safer Care Victoria’s Partnering in Healthcare framework45. The DWECHS Operations Manager (June 2019) identified the LHAY project as a key to formalising the organisational Statement of Intent, with the documented process of community engagement seen as a strength of the submission.

Importance of flexibility and adaptability in the research process

The LHAY project also supported the need for researchers to be flexible and adaptable to the needs of Aboriginal community members throughout the research process, particularly when using a PAR framework. Flexibility and adaptability have also been identified as important elements of the research process in other Aboriginal health research undertaken in rural Victoria46. A PAR framework allowed for flexibility of research activities as relationships were developed between researchers, other needs were identified, and opportunities arose to link in with other activities occurring at DWECHS. However, a key challenge for the LHAY project, which required adaptation, was personnel changes throughout the project, which has been previously documented as a challenge in other Aboriginal research44. The key personnel change with most potential to disrupt project delivery was the senior project officer because the coordination and inclusion of Aboriginal community members largely depended on senior project officer engagement. In future, effort needs to be made to find the balance between identifying and supporting suitable project coordinators from partnered organisations and allowing for flexibility in the research plan. This did not affect the timelines of the LHAY research project as extensions were sought and obtained from the funding body. However, in other Indigenous health research, meeting the timelines stipulated by funding bodies has been cited as a key challenge, particularly when extra time is required for community engagement47.

Recommendation for greater provisions protecting intellectual property

A recommendation identified through the CONSIDER statement as part of the LHAY project was the need for a specific clause in the CRA or another formal research agreement that explicitly protects the intellectual property of the partnered Aboriginal community. Although reporting research against the CONSIDER statement provides a mechanism for accountability retrospectively, prospective measures should be implemented. There is a growing awareness of the importance of data sovereignty and ownership in Indigenous health research48.

Limitations

Limitations of using the CONSIDER statement to critically reflect on research include the risk of recall bias. No formal follow-up of Aboriginal community members who attended the CBSD lunches was conducted. Whether community participants were fatigued by the burden of CBSD lunches (a risk of PAR), felt rightfully empowered by the experience or otherwise is unknown, which is a limitation of the research44. The CONSIDER statement could also be used prospectively as a guide for researchers when partnering with ACCHOs in the research process. This would require further consideration as to how the CONSIDER statement aligns with the National Health and Medical Research Council’s Human Research Ethics Application49 to not duplicate the use of guidelines.

Conclusion

Using the CONSIDER statement to undertake a structured, critical reflection on a PAR research project undertaken in partnership with a rural ACCHO was beneficial in identifying key issues and lessons learned. This included identifying that developing a research partnership with an ACCHO based on respect and reciprocity was key to setting the research agenda and expectations. Using a PAR framework allowed the research to be flexible and adaptable, with outcomes of relevance for the local community, and participating ACCHO. The types of research activities undertaken, key issues and lessons learned are likely to be transferrable to other settings. This includes the recognition for greater protection of Aboriginal intellectual property, data sovereignty and ownership in research through formal agreements.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to the community members, including Elders, who attended the lunches and provided insights throughout the project. They acknowledge Peter Harvey (Deakin Rural Health), Constance Kourbelis (Flinders University), and Annie Henry, Louis Delany and Allira Maes (DWECHS) for their input over different phases of the project.

References

You might also be interested in:

2011 - Health promoting community radio in rural Bali: an impact evaluation

2005 - Rabies surveillance in the rural population of Cluj County, Romania