Health professionals for a pandemic response

Health professionals have found themselves at the global frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic. An acute global shortage of appropriately trained health professionals and equipment to handle a pandemic is apparent. Clinical training has not prepared graduates well for public health emergencies, and health professionals at the coalface have confronted the uncertainty and anxiety provoked by COVID-191. Here, we discuss the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education and how we must seize the moment to produce a fit-for-purpose health workforce. This workforce must be ready to respond to pandemics and address the social injustice and inequalities COVID-19 has revealed, including their effects on vulnerable populations. In our view, this is a transformational moment for medical education; a disruptor offering opportunities for true reform. Achieving this requires integration of competency-based, place-informed health education with virtual care, informatics and attention to both health system and physician resilience while rethinking the scope and breadth of the health team trained to meet looming challenges.

Learning from the impacts of the pandemic on medical education

There have been many adjustments over the past year, including suspension or restrictions on medical student clerkships and campus-based learning, wholesale moves to remote and online learning, use of the virtual environment for clinical skills and laboratory sessions, online examinations, adaptation of accreditation requirements and sending students out into the community to help. COVID-19 has also highlighted the embedded inequities and fragmentation in our health systems, shedding light on unfair financing, service delivery and education models that systematically exclude the most disadvantaged from health care and education options2,3.

An important topic that has yet to receive much attention is how these adaptations and disruptions in conventional approaches to medical education might actually help drive greater social accountability of health professional schools towards the populations that they serve.

For example, given the COVID-19 experiences, how might we now approach medical program design that educates and trains graduates ‘from, in, with and for’ underserved and rural communities? How might medical education adapt to evidence of service interventions measurably improving community health? How might community priorities become the driver of academic programming rather than academic priorities being the main driver of what is offered to communities? How might the challenges imposed by the COVID pandemic accelerate responsiveness, adaptability and the pace of change? For example, rapid deployment (and uptake) of telemedicine for clinical care (previously thought too difficult) can also facilitate distributed teaching and learning models4. Additionally, growing recognition of the role of community health workers in promoting community health now finds them integrated into the health system and healthcare teams5.

Implications of COVID-19 for ongoing medical education

The United Nations High Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth argued that an increased investment in health workforce must yield better societal outcomes, effectively and efficiently6,7. In medical education, there are many examples of public spending on medical workforce (often in the name of underserved and rural populations) translating instead to urban medical subspecialisation, fragmentation of care, inefficient and ineffective health spending and economic medical migration3. This pandemic caught health systems by surprise. More than 80% of hospitalised COVID-19 patients had underlying conditions easily treatable by primary care teams8. Yet, health systems and traditional medical education are still specialty driven, with insufficient emphasis on primary care or integration of public health into clinical education and basic health systems9,10.

Effective and efficient care demands high quality primary care and social services for:

- appropriate community-based triage, testing and tracing

- prevention and treatment of comorbidities in the communities where patients live

- strong integration with hospital care when needed10,11

- broadening the scope of medical education to encompass skills in population health and intersectoral bridge-building.

It is no surprise then that key strategic challenges for medical education include:

- promotion of ‘generalist’ careers among medical graduates12,13

- achieving a more equitable geographic distribution of medical workforce

- growth of public health degrees and certificates as medical school options14

- in-country retention of medical graduates in low- and middle-income country (LMIC) settings.

Promoting the ‘social mission’ of medical schools and other health education institutions is seen as an important way to contribute to better health outcomes3. The development of ‘socially accountable medical education’ and the practical learning among medical schools committed to this agenda are highly relevant in this regard.

THEnet: a community of practice for social accountability in health professional education

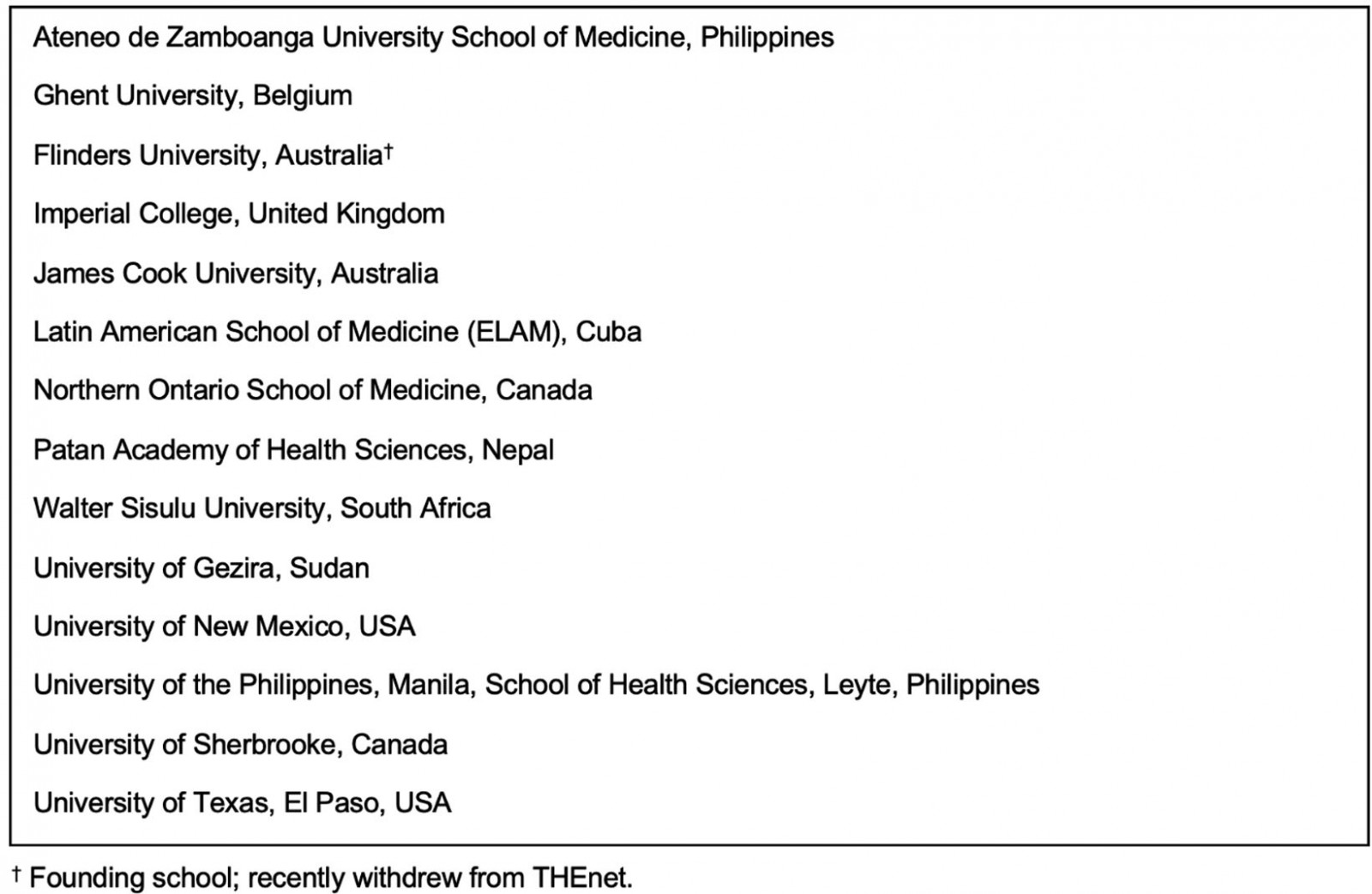

The Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) is a community of practice of 13 medical and health professional schools with a commitment to producing and supporting a health workforce to meet the needs of the communities they serve (Box 1). Located largely in rural and underserved areas of 10 low- and high-income countries, these schools share a focus on:

- recruiting students from underserved and under-represented populations

- providing a balanced curriculum with a primary care focus that integrates the psychosocial, biological and clinical sciences

- delivering the program in large part in the community in underserved areas

- providing postgraduate training options that address local health workforce needs15.

Box 1: Health professional schools in the Training for Health Equity Network

THEnet is a learning network, where innovations are shared among members and across sectors, but where member schools learn from institutions across the globe and share their innovations in kind. Evaluation to hold ourselves accountable for outcomes is an important part of this work. Our research shows excellent outcomes in terms of intentions to practice and actual practice in rural and underserved areas, practice in generalist disciplines, broadening the health team to include community-based health workers16 and health extension regional officers17, and remaining in country to serve rather than emigrating, for LMICs18. Longer term data from some schools suggest that these intentions translate well into actual practice19,20.

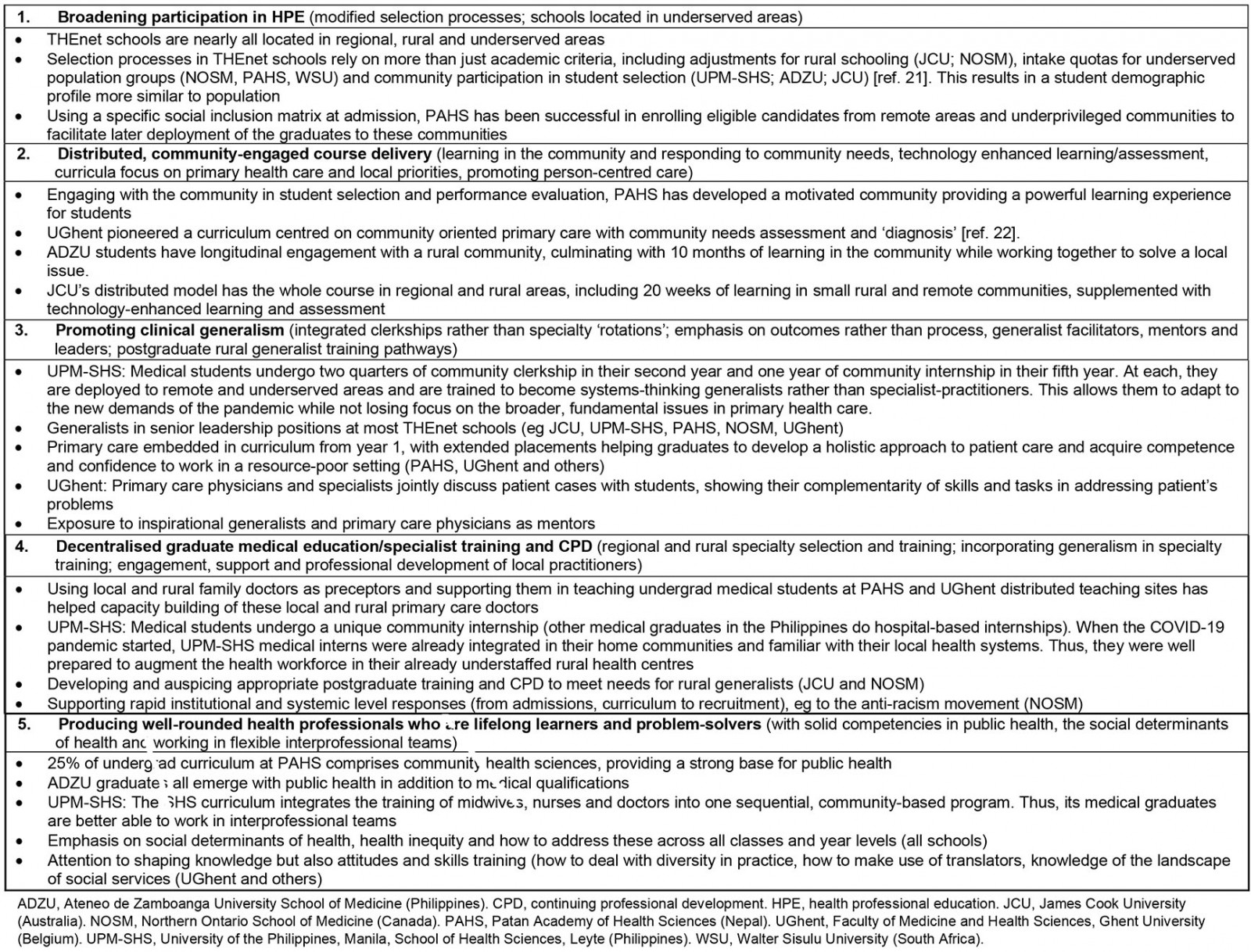

Many of these innovations, used with demonstrated success in THEnet schools, may be of considerable utility to other medical schools trying to adapt their ways of doing things to a post-COVID world, while advancing social good and health equity. Some examples follow from THEnet partner schools of innovations that, as a result of COVID-19, may now have accelerated adoption among mainstream schools (Box 2).

Box 2: Examples of prosocial innovations in education from THEnet schools21,22

Moving forward: educating future health professionals

To play an optimal role in strengthening societal health and wellbeing, health professional schools must respond and hold themselves accountable for addressing regional health and health system needs. Accreditation of medical schools needs substantial reform with new standards that require schools to prepare physicians to be competent to treat marginalised and vulnerable populations. As leaders in health professional education, we see a role in assisting health systems to respond quickly to emerging crises with pre-emptive disaster planning that includes necessary adjustments to health professional training to ensure that our students and graduates are important drivers of change into the future.