Context

British Columbia, Canada

British Columbia (BC) is a vast province, located on the western coast of Canada, with a population of just over five million residents1. Of these, approximately 2.6 million residents, or over 50%, are concentrated in the small, geographic area of Greater Vancouver. The rest of the province is considerably less densely populated, and 13.6% of the population live in small, rural and remote communities across the province’s land mass2. BC’s health system is centralized and fragmented, with little formal communication or coordination3,4. The structure of BC’s healthcare system, combined with unique geographical, contextual, and cultural factors, has caused rural communities to experience enduring health inequities5-8. For example, rural and remote communities, which are often home to more Indigenous residents and those with lower socioeconomic status, experience structural inequities and disparities in access to care, such as the requirement for extensive and costly travel9,10. Virtual health care (VH) has been proposed for and advocated as a solution to mediate health inequities for those living in rural and remote communities.

Virtual health care

VH involves the remote offering of health-related information, services, and/or supports using a range of technologies (eg telephone, e-mail, text message, video call, smartphone application)11. VH is considered to be a substantial innovation for its ability to improve quality of care and access to primary and specialized services, while carrying the potential to lower expenditures across the healthcare system12,13. Positive implications of using VH include decreased need for travel, decreased waiting times, increased convenience, and improved cost efficiency14. For example, telemedicine appointments have been shown to save US$19–121 per visit, as these appointments address concerns without accessing other resources (eg emergency departments)14. When VH is used in rural and remote communities, patients and healthcare providers can be supported to receive and deliver high-quality healthcare experiences. Patients have expressed that high-quality VH can lead to increased feelings of empowerment, improved self-management, increased access to culturally appropriate care, and reduced barriers associated with travelling (eg costs, lost work wages)15-17. For patients living with chronic conditions, VH can remove structural barriers (eg inaccessible doctor’s offices) that impede the ability to attend appointments. For healthcare providers, using VH can allow them to diversify their knowledge and skillsets, and build and maintain collaborations, both of which can contribute to improving the overall quality of care they can provide15,16. For example, in BC, teletrauma programs have enhanced the capacity for local trauma care in rural communities by connecting rural communities in real time with colleagues from urban centers who have specialized trauma knowledge18. VH can also be used to support healthcare systems to improve the accessibility and equity of their healthcare services. Attending to equity and accessibility may decrease the health inequities that rural and remote communities endure. While VH has been demonstrated as an important way to improve access in rural and remote settings, critical barriers and inequities exist19,20.

Issue

The COVID-19 pandemic

Worldwide, the rapid evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic has forced healthcare systems to promptly transition to primarily VH options. Through the agile and rapidly changing integration of VH, multiple strategies emerged to support the delivery of healthcare services to patients in the context of enduring physical distancing restrictions and critical demands due to COVID-19.

Despite the many advantages of VH, the unexpected nature of the pandemic caused the transition to occur haphazardly, and while unintended has exacerbated some pre-existing and introduced new health inequities between urban and rural and remote communities21. For example, insufficient broadband internet capacity has resulted in a lack of access to a range of healthcare services in rural areas of BC22. Likewise, rural communities often lack adequate infrastructure, including the technical supports necessary for fulsome VH services23. Beyond access, concerns about the quality of care received through virtual platforms throughout COVID-19 have been raised, including the potential for fragmented and lower quality care24. For rural and remote communities, VH is continuing to evolve. Thus, to ensure quality VH, the unique needs and context must be identified, prioritized, and addressed. Health system planners must consider the differences in how rural and remote communities view and use healthcare services25, as well as differences in access to and use of technology26.

A potential solution: knowledge translation

When designing and implementing VH options for rural and remote communities, enacting equity-informed knowledge translation (KT) processes may help to ensure that VH options are evidence-based, accessible, and responsive to patient needs27. In the Canadian context, KT has been defined as ‘a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products and strengthen the healthcare system. This process takes place within a complex system of interactions between researchers and knowledge users which may vary in intensity, complexity, and level of engagement depending on the nature of the research and the findings, as well as the needs of the particular knowledge user’28. From an equity perspective, adopting an equity-informed KT approach would ensure the voices of those with lived experience of health inequities are meaningfully included when making decisions about developing and implementing VH options.

To create equitable health services in rural and remote areas, health system planners must proactively rather than reactively engage community members’ perspectives into priority setting and service planning. Using an integrated KT approach, which involves ongoing collaboration between a variety of relevant stakeholders, can help to ensure their unique perspectives and needs are incorporated at every stage, from defining the problem to developing and assessing solutions29. While specific resources that guide the process of adopting equity-informed KT approaches have been developed30, routine use of these resources within health care is uncommon.

A journey of research co-production

The authors of this commentary represent a diverse group of researchers and healthcare practitioners who reside in BC. All authors of this commentary reside outside of the Greater Vancouver area, and have lived experience of navigating healthcare systems from outside this central urban hub. Each author also has an interest and passion in the practice and science of KT. These passions influenced each author to engage in the Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research (CCGHR) Knowledge Translation Program, either as a trainee or mentor. This course seeks to promote KT theory and practice through a focus on research co-production and relational practice to address equity and global health concerns. This open-access program empowers learners to examine critical health issues from an equity standpoint, addressing theoretical, practical, and applied aspects of KT.

Brought together by common geographic, personal, and professional factors, the authors began discussing topics that were most relevant to supporting rural communities in BC. As these discussions took place amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of COVID-19 on rural communities quickly became an integral area of interest. Drawing from personal experiences and perspectives, the group agreed that preparing rural residents for optimal VH experiences was a relevant and impactful topic to explore.

This commentary aims to describe the equity-informed KT process that the authors engaged in during their time enrolled in the CCGHR program, and highlight how usable and accessible KT products were developed as a result of authentic partnership building.

Lessons learned

The equity-informed integrated KT approach

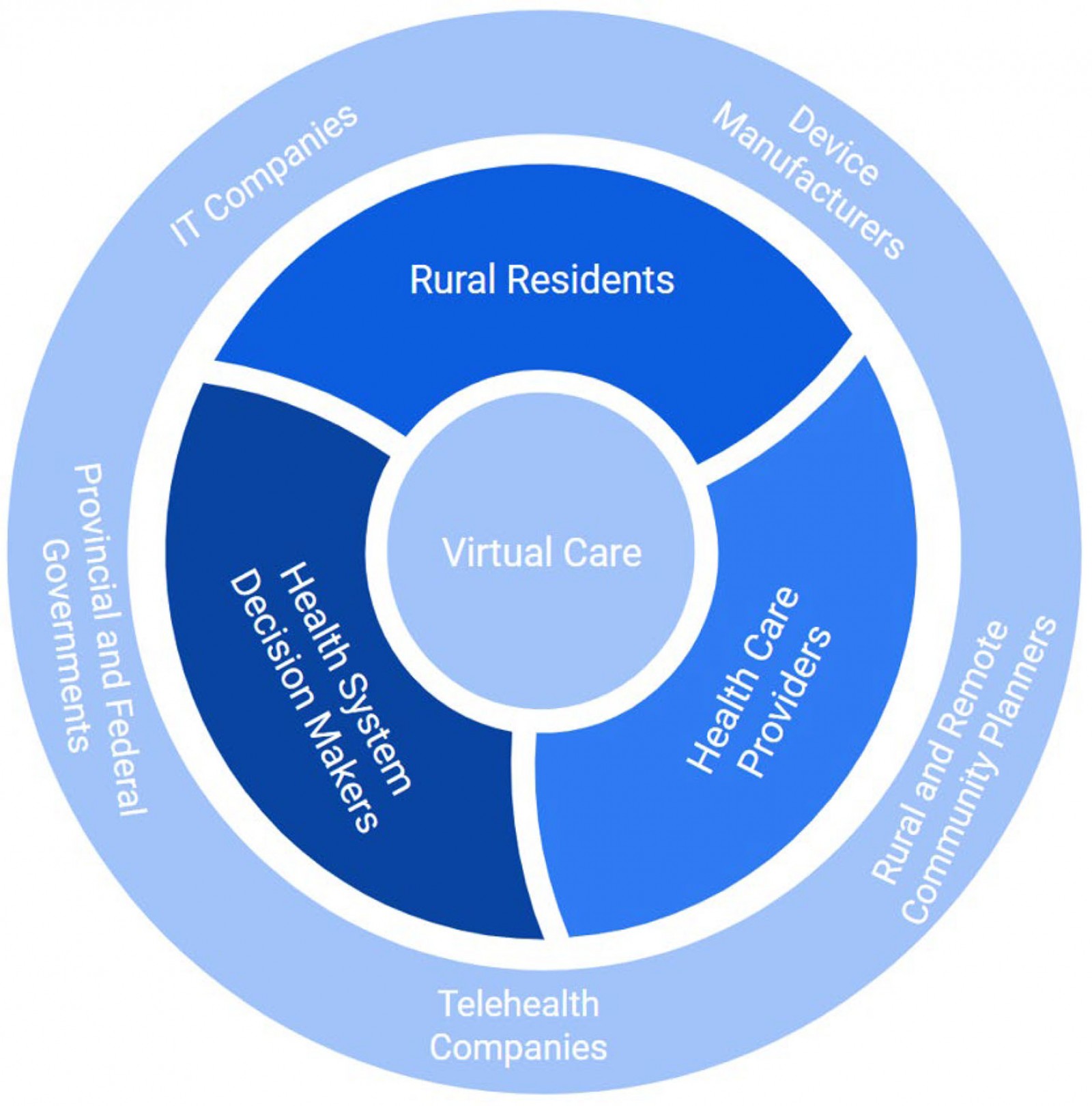

The authors recognized how the rapid expansion of VH during the COVID-19 pandemic provided a window of opportunity to proactively, rather than reactively, consider equity in addressing the group’s aim. Identifying relevant stakeholders started with understanding who should be included in decisions around developing and implementing VH interventions in rural and remote communities (Fig1). Stakeholders were ultimately selected through the senior author’s network for their expertise, knowledge of VH, and engagement with diverse patient populations from across the health system, including those who face structural barriers and challenges. The group’s mentor facilitated the development of an authentic partnership with five stakeholders from rural and remote communities in BC (one patient, three healthcare practitioners, one healthcare administrator). Following an integrated KT approach, the CCGHR learners engaged in facilitated discussions, consultation of the literature, and information synthesis to determine appropriate KT products to prepare rural residents to experience optimal VH. Each stage was informed and guided by the CCGHR’s Principles for Global Health Research, a set of six values (authentic partnering, inclusion, shared benefits, commitment to the future, responsiveness to causes of inequities, humility)30 and critical reflective questions that aim to integrate equity throughout research, regardless of subject matter.

Discussions were facilitated by a semi-structured question guide (Appendix I). An example of how equity was prioritized in this discussion was through intentionally having the patient begin the stakeholder discussions, followed by the healthcare practitioners and administrator. Further, the group adopted inclusive and sensitive engagement, ensuring that the voices of all involved were heard and that all parties felt safe and supported when sharing their perspectives and viewpoints. This type of engagement ensured that the team proactively attended to potential power imbalances within the group and supported open exchange and dialogue. The discussion was also structured to allow ample time to process and reflect on others’ contributions to the conversation. Relevant evidence from the literature was shared during the discussion as a means of integrating emerging best practices.

Drawing from the stakeholders’ unique knowledge and perspectives, all partners highlighted the importance of developing two preparatory VH tip sheets to support patients and healthcare providers for optimal VH appointments. Using the synthesis of the stakeholder discussions and consultation of the literature, the initial versions of the tip sheets were developed by the authors, and sent to the entire partnership to review and refine. Both sheets use accessible language to outline a temporal set of actions that residents (Appendix II) and healthcare providers (Appendix III) can follow to enhance VH appointments. The content of the tip sheets represent a synthesis of stakeholder suggestions and literature-identified promising practices.

Figure 1: Visual representation of individuals, groups, and communities who should be included in decisions around developing and implementing virtual healthcare interventions in rural and remote communities.

Figure 1: Visual representation of individuals, groups, and communities who should be included in decisions around developing and implementing virtual healthcare interventions in rural and remote communities.

Equity-informed KT products: tip sheets and open-access report

During our discussion, the patient partner reflected upon their experience of engaging with various aspects of the healthcare system through VH, including primary care and specialized services, while navigating multiple structural inequities and personal challenges. On an individual-interactional level, the patient partner discussed how elements of relationality and holistic assessment are often missing from VH appointments, and that there can be obscurity or misunderstandings about the intention and structure of appointments, leading to poorer health outcomes. Similarly, healthcare providers and administrators shared the challenges of delivering VH services in the absence of dedicated resources and supports, noting that they needed to be nimble and responsive when determining the best methods for supporting VH.

A recent study suggested that e-health literacy, or the ‘capacity to understand and have personal and technical comfort with the receipt of health care through technology’, is an essential part of the success of VH in rural contexts17. The tip sheets are a KT tool aimed at building e-health literacy, and responding to the unique rural health inequities identified during the integrated KT process. In addition to the idea of developing the tip sheets that emerged from stakeholder conversations, examples of equity considerations embedded throughout include plain language, tips for various modes of accessing VH, considerations of multiple practitioners, and prompts for providers to proactively inquire about barriers to quality care.

At a systems level, the authors learned that the rapid shift to primary reliance on VH can be concerning as VH can further isolate individuals and groups who lack access to necessary infrastructure (eg reliable internet connection, affordable devices), social support (eg after receiving difficult medical news), and/or capacity to engage virtually (eg technology literacy or language barriers)31-34. While many rural and remote communities have made longstanding calls for increased VH options, there is a resounding message that VH is useful as one piece of the health care continuum, not as a replacement for robust, in-person care26. Advancing rural VH requires context specific considerations and consultations to be intentionally woven into research, policy, planning, and implementation. In response, the authors produced an open-access report that delves deeper into rural VH equity. Ultimately, the authors leveraged an equity-informed KT process to produce multiple tools that engage different stakeholders.

Overarching lessons

Incorporating the perspectives and experiences of diverse rural and remote community members into decision-making processes around VH is essential for moving towards more equitable systems and high-quality use of VH rurally. Those who reside in rural and remote areas are best equipped to know how the healthcare system works for them and are well positioned to identify mitigating strategies to address gaps in the system. When lived experience is used synergistically with academic knowledge and political will, the goal of an equitable healthcare system becomes increasingly conceivable35.

VH holds immense promise as a healthcare tool to increase access, improve patient experience, and reduce patient and system-level costs. Perspectives from diverse rural and remote stakeholders – patients, support networks, and providers – must be included in decision making and implementation processes to ensure their unique needs and priorities are meaningfully addressed. Equity-driven KT processes can support these goals and lead to stronger rural and remote health systems. While the KT tools developed from this work are an example of equity-informed tools, they are not a sole solution. As the COVID-19 pandemic persists and eventually wanes, efforts to support equitable access to VH must continue in a way that meaningfully involves the voices of all who are directly impacted, regardless of where they live.

Acknowledgements

This commentary is the product of participation in the Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research Knowledge Translation Program. The authors appreciate the opportunities and guidance provided by the program’s developers and instructors: Dr Katrina Plamondon, Dr Vic Neufeld, Emily Kocsis, and David Walugembe. The authors also acknowledge and appreciate the contributions of the patient and healthcare stakeholders who contributed their time and perspectives to inform this work.

References

You might also be interested in:

2021 - Rural health research capacity building: an anchored solution

2017 - Gene therapy renews hope to lower the global rural sickle cell disease burden

2013 - Recruitment and retention of rural nursing students: a retrospective study