Introduction

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs), like other primary care organisations in Australia and internationally, were required to respond rapidly to physical distancing requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic1,2. A key component of the response was the adoption of telehealth to continue meeting the healthcare needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples1. Temporary changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item numbers (the funding structure of Medicare, the Australian universal healthcare system) accommodated for telehealth delivery using both videoconferencing and telephone3, which provided ACCHOs with additional options to engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients through COVID-19.

In Australia, over 140 ACCHOs are located geographically proximal to where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples reside4. Further, ACCHOs are valued for the provision of culturally appropriate holistic primary health care and are well positioned to address barriers to accessing health care (eg racism, transport, cultural needs)5. As approximately 44% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples reside in Inner and Outer Regional Areas of Australia6 (encompassing Modified Monash category (MM) 2–Regional centres to MM 5–Small rural towns)7, ACCHOs located in these areas are particularly important to the delivery of primary healthcare services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples who also experience additional barriers to accessing health care attributed to the rural context (eg geographical accessibility of services, availability of health professionals and other resources)8.

While telehealth is not a novel intervention, COVID-19 proved to be a catalyst for the rapid and widespread adoption of telehealth in ACCHOs across Australia2. Literature examining the implementation of telehealth prior to COVID-19 has been largely focused on the delivery of specialist telehealth services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples9 and to people residing in rural areas10. There has been little examination of the delivery of telehealth primary healthcare services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples residing in rural areas, including the acceptability of telehealth11. Evaluating this is important to informing policy and practice around the implementation of telehealth in this setting and in other primary care organisations, particularly for populations who otherwise experience geographical inequities when accessing health care. This study meets the need for evaluating telehealth primary healthcare services delivered for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples by a rural ACCHO during COVID-19.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the implementation (specifically the uptake, acceptability and requirements for delivery) of telehealth primary healthcare services to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Peoples by a rural ACCHO during COVID-19. The study examined three key evaluation questions: ‘What was the uptake of telehealth consultations by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients of a rural ACCHO?’, ‘Was telehealth an acceptable model of service delivery from the perspectives of health service personnel and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients?’ and ‘What were the requirements for the ongoing delivery of telehealth in a rural ACCHO?’

Methods

Study design and setting

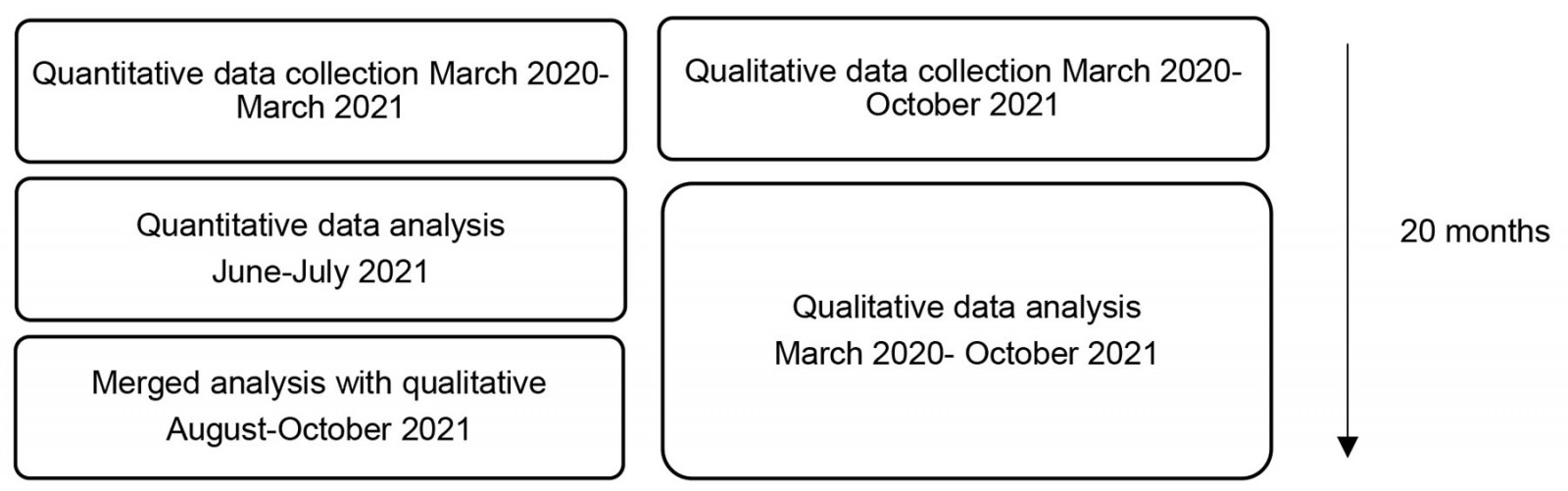

A convergent–parallel mixed-methods study design12 using a community-based approach (see Appendix I under Methodologies) was used to undertake the evaluation over a period of 20 months to capture different stages of implementation and impacts of policy changes (Fig1). This involved collecting quantitative data and qualitative interview data concurrently, undertaking respective analysis and converging the interpretation of findings12. Like other ACCHOs, telehealth was not utilised for standard GP appointments at this ACCHO prior to COVID-1913.

The study was undertaken at a single site in the context of an ongoing research partnership established between a rural ACCHO (located in Halls Gap, Victoria; Modified Monash Model 5–Small rural town where 6.6% of the Victorian population reside)7,14, Budja Budja Aboriginal Co-operative (BBAC) and Deakin Rural Health (DRH, a university department of rural health funded by the Rural Health Multi-Disciplinary Training (RHMT) program)15. In Australia, the RHMT program supports the training of rural health students and a research agenda specific to the rural context, which includes the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples16. The purpose of the ongoing partnership is to evaluate the implementation of new models of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the BBAC service area and to identify opportunities for improving service delivery17. The partnership was developed from 2018 with the implementation and evaluation of a community-developed model of primary healthcare service delivery, the Tulku wan Wininn mobile clinic18,19.

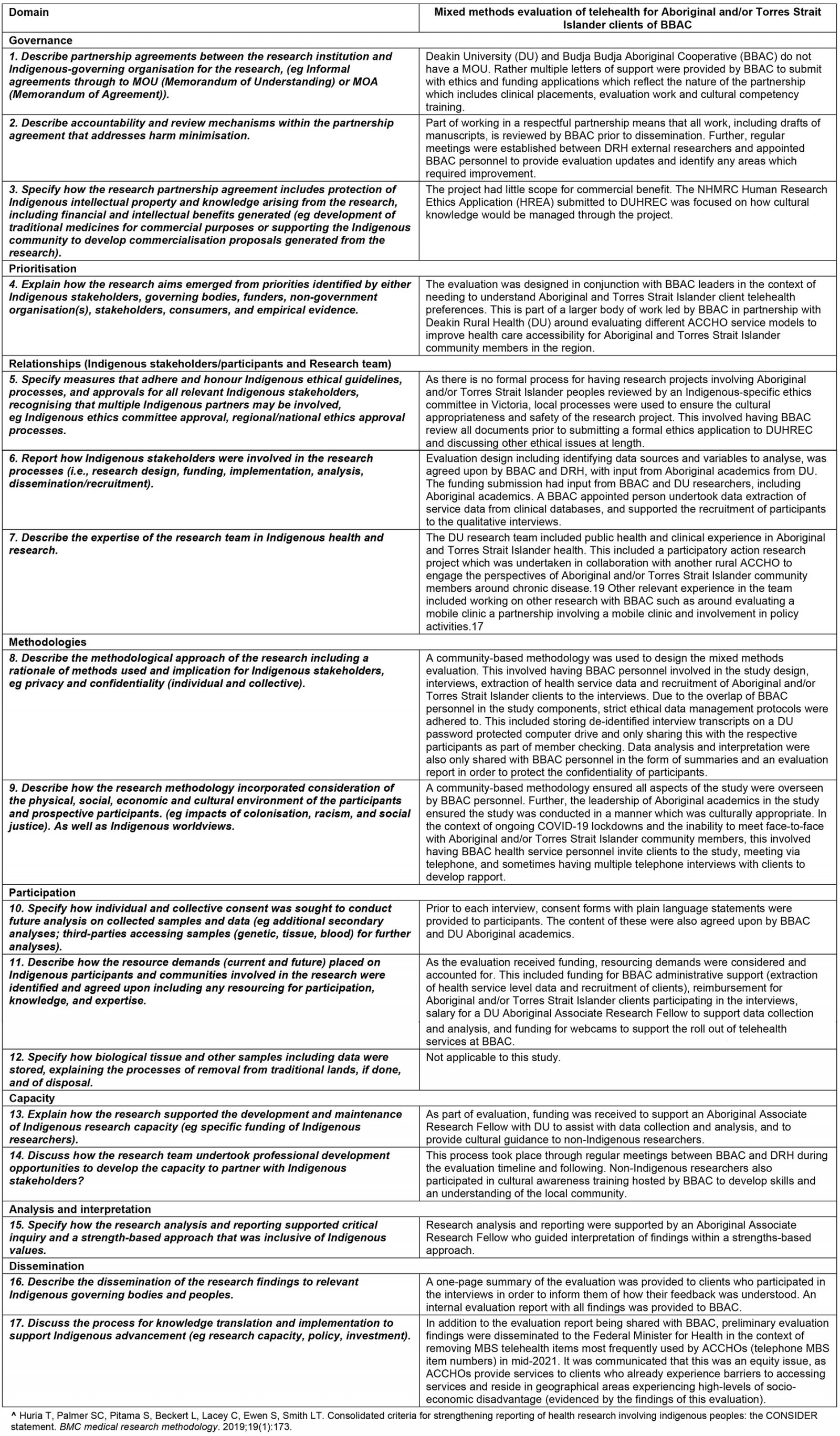

The study was reported using the CONSolIDated critERia for strengthening the reporting of health research involving Indigenous Peoples (CONSIDER) statement (Appendix I)20 for transparency of the ethical and cultural approaches used to undertake the research – an approach used by other research undertaken in partnership with a rural ACCHO21.

Figure 1: Convergent–parallel mixed-methods study design.

Figure 1: Convergent–parallel mixed-methods study design.

Participants and recruitment

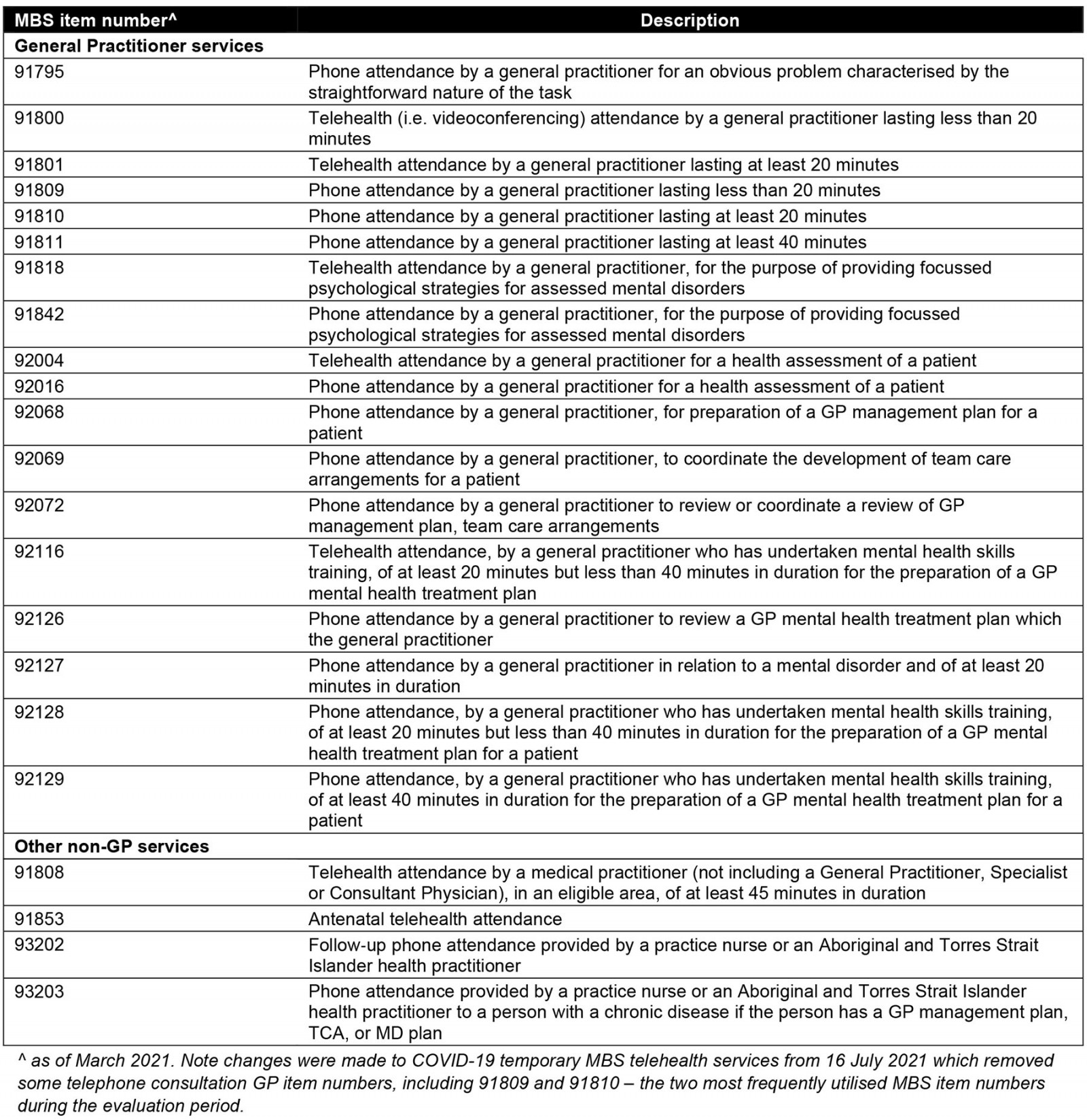

Quantitative data: Service-level data eligible to be included were telehealth consultations undertaken at BBAC from March 2020 to March 2021 with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients. Eligible MBS telehealth item numbers included GP and non-GP services used by BBAC (Appendix II). Non-Indigenous telehealth consultations were excluded. Consultations meeting the eligibility criteria were identified by BBAC using Pen CS Clinical Audit Tool (PEN CAT) and Medical Director (see Appendix I under Relationships).

Qualitative data: Purposive sampling was used to identify health service personnel (including health professionals) involved in the implementation of telehealth services at BBAC who were directly invited by external DRH researchers to participate in a semi-structured interview. External DRH researchers had prior rapport with most health service personnel due to the nature of the ongoing collaborative partnership between DRH and BBAC17. A mutually convenient time for an interview was arranged. A plain language statement was provided after an interview time was booked. Informed written consent was then obtained prior to the interview.

Purposive sampling was also used to identify Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander adult clients (aged 18 years or more) who had accessed primary healthcare services using telehealth through BBAC during COVID-19. Non-Indigenous clients who had accessed telehealth services were excluded. Recruitment was initially managed by BBAC as per the principles of data sovereignty and client confidentiality (see Appendix I). A letter of invitation was mailed to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients by a BBAC staff member, and they were then identified by the BBAC Practice Manager as having accessed telehealth services between March 2020 and March 2021. The letter detailed information about the study, including what participation would involve. For clients interested in participating in this study, permission was obtained from clients by BBAC to pass contact details on to external researchers. A mutually convenient time for an interview, undertaken either by telephone or Zoom (as allowed by COVID-19 lockdown restrictions at the time) was arranged where a plain language statement was provided. Informed written consent was then obtained prior to the interview. Participants were reimbursed for their time with a voucher.

Data collection

Quantitative data: Health-service-level consultation data from 17 March 2020 to 31 March 2021 were extracted manually from PEN CAT and Medical Director using the report function by a BBAC-nominated person, as per the principles of data sovereignty and governance (see Appendix I)22. Data were de-identified by a BBAC-nominated person. De-identified consultation data (age, gender, MBS item number and postcode) were provided to external researchers from DRH in a spreadsheet for analysis in accordance with the evaluation plan.

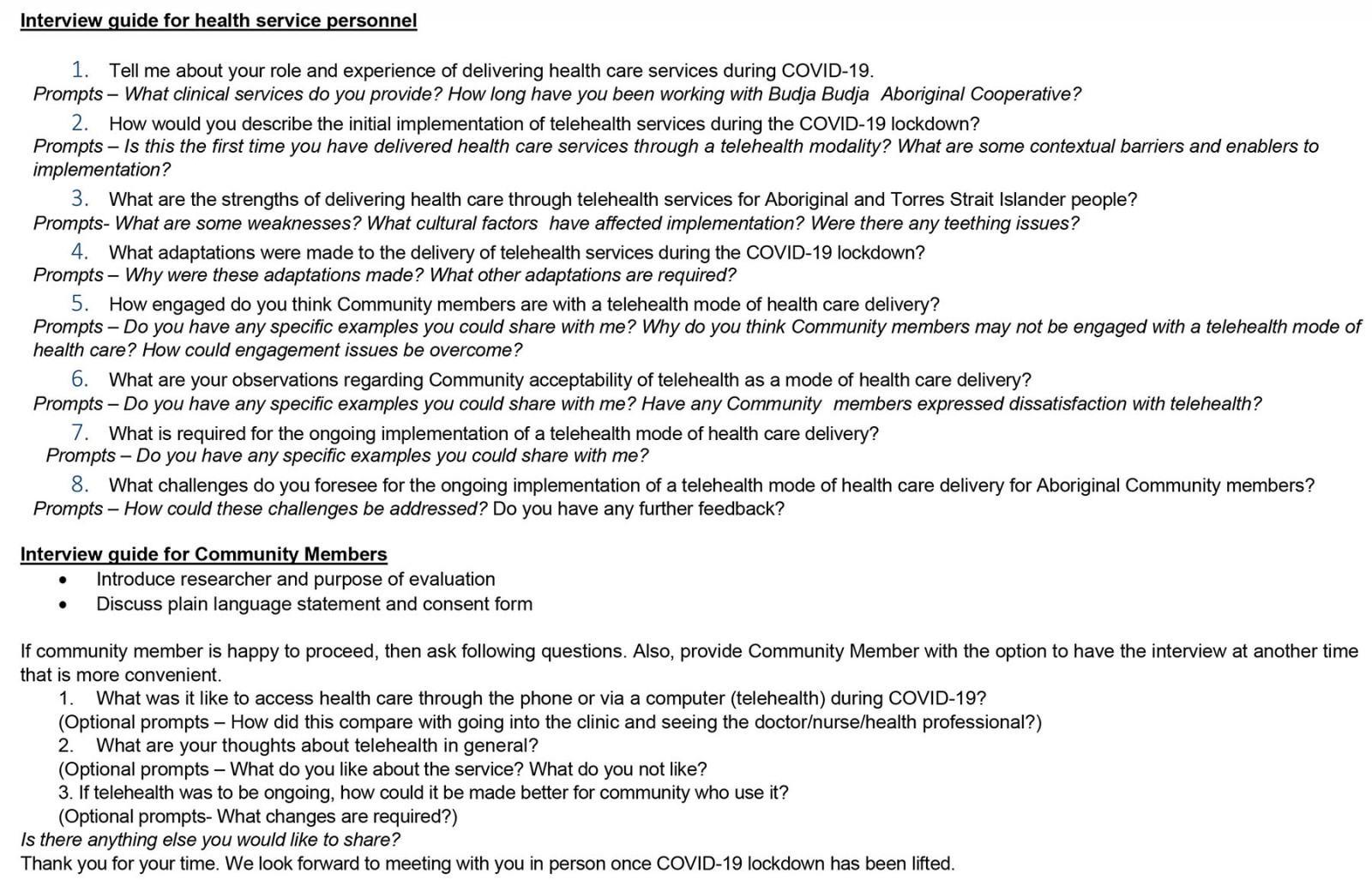

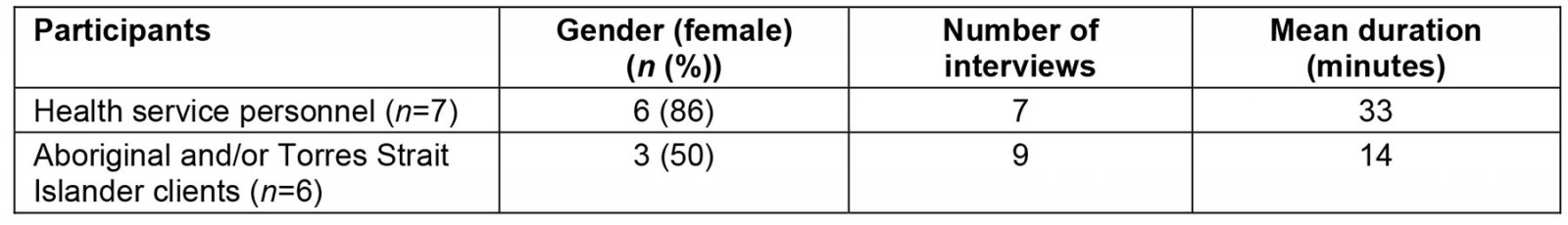

Qualitative data: Semi-structured interviews were undertaken from March 2020 to October 2021, to capture the different stages of implementation in parallel with the collection and analysis of health-service-level data. Interviews were conducted remotely using videoconferencing and telephone to comply with COVID-19 physical distancing restrictions. Two topic guides were developed: one for health service personnel and the other for clients (Appendix III). Questions explored the experience of participants in either implementing, delivering or accessing telehealth primary healthcare services and the perceived acceptability of telehealth for the delivery of health care. Two researchers, one of whom is Aboriginal, who both had experience in qualitative data collection, conducted the interviews. The mean duration of interviews was 33 minutes for health service personnel and 14 minutes for clients. Researchers undertaking the interviews participated in a debrief following the interviews to discuss emerging ideas and to critically reflect on the interviews using reflexive practice, which also considered the positioning of researchers and their relationship with participants23.

Data analysis

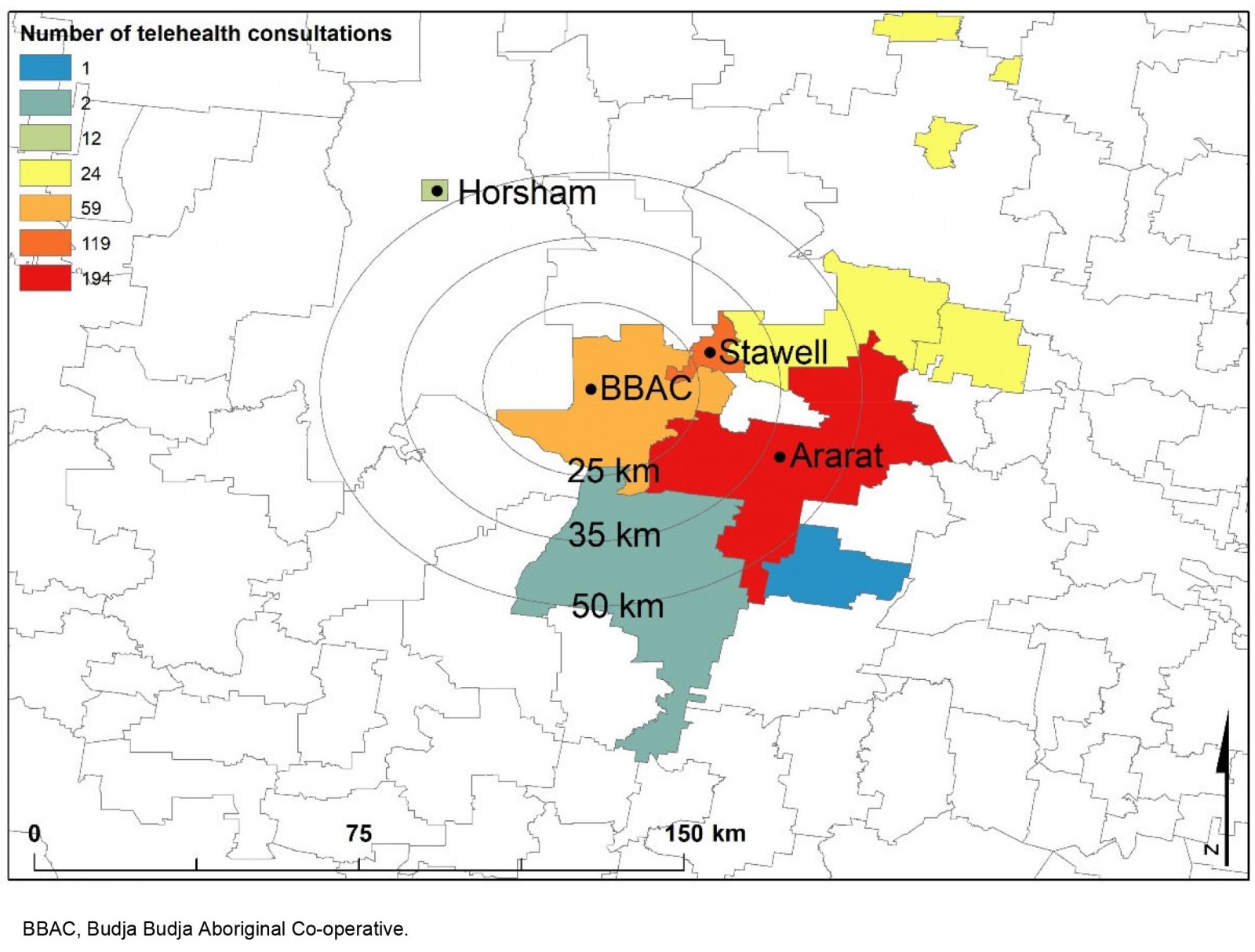

Quantitative data: Descriptive analyses of de-identified health-service-level data were undertaken in Microsoft Excel, with frequency distributions, proportions, ranges, medians and interquartile ranges generated where appropriate at the aggregate level to identify consultation uptake. Summaries were visually presented in the form of graphs and tables. Consultation frequency by postcode, overlaid with the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) data (deciles relative to the Australian population)24, were mapped. This analysis included proximity to the BBAC fixed clinic, with data displayed geographically using ArcGIS map ArcMap v10.6.1 (ESRI; https://www.esri.com/arcgis-blog/products/arcgis-enterprise/announcements/whats-new-in-arcgis-enterprise-10-6-1).

Qualitative data: All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A copy of transcripts was provided to participants for member checking. Transcripts were imported into NVivo v12 Plus (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo) for analysis. The same two researchers involved in collecting the data also thematically analysed the data25. This involved inductive first-cycle open coding, which was undertaken independently and focused on the acceptability of telehealth and requirements for implementation26. Codes and categories were then compared and merged to form a coding framework. Second-cycle coding utilised more focused coding26. Themes were then developed from the refined coding framework.

Convergent analysis: Qualitative themes were then mapped to findings from the quantitative analysis, and key concepts were developed. Findings were provided to BBAC in the form of an internal evaluation report and to clients, who participated in an interview in the form of a plain language summary.

Ethics approval

Human research ethics approval was provided by the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol 2019-432). A letter of support for the research was provided by BBAC as part of the ethics process.

Results

Three concepts that met the study objectives were developed from an interpretation of the quantitative and qualitative findings: uptake of telehealth consultations by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients, maintaining the delivery of ACCHO services during COVID-19, and implications for sustaining telehealth in an ACCHO.

From March 2020 to March 2021, BBAC delivered 435 telehealth primary healthcare consultations to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients, either by telephone or videoconferencing, across the Northern Grampians and Ararat regions of Victoria, Australia. Seven health service personnel and six Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients participated in interviews, with three interviews repeated with clients (nine total client interviews) at different time points of the study (Table 1).

Table 1: Interview participants

1. Uptake of telehealth consultations by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients

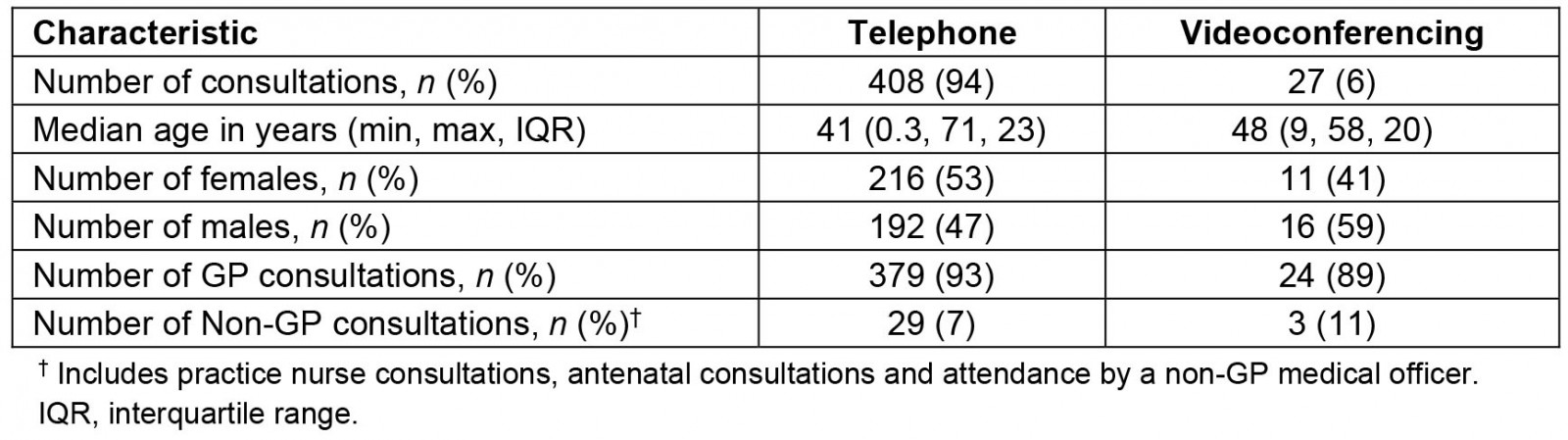

Of all clinic consultations delivered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients during this period (n=1107, a number that includes face-to-face consultations), 39% (n=435) were telehealth consultations. Of all telehealth consultations delivered, the majority were conducted using the telephone (n=408, 94%), rather than videoconferencing (n=27, 6%) (Table 2).

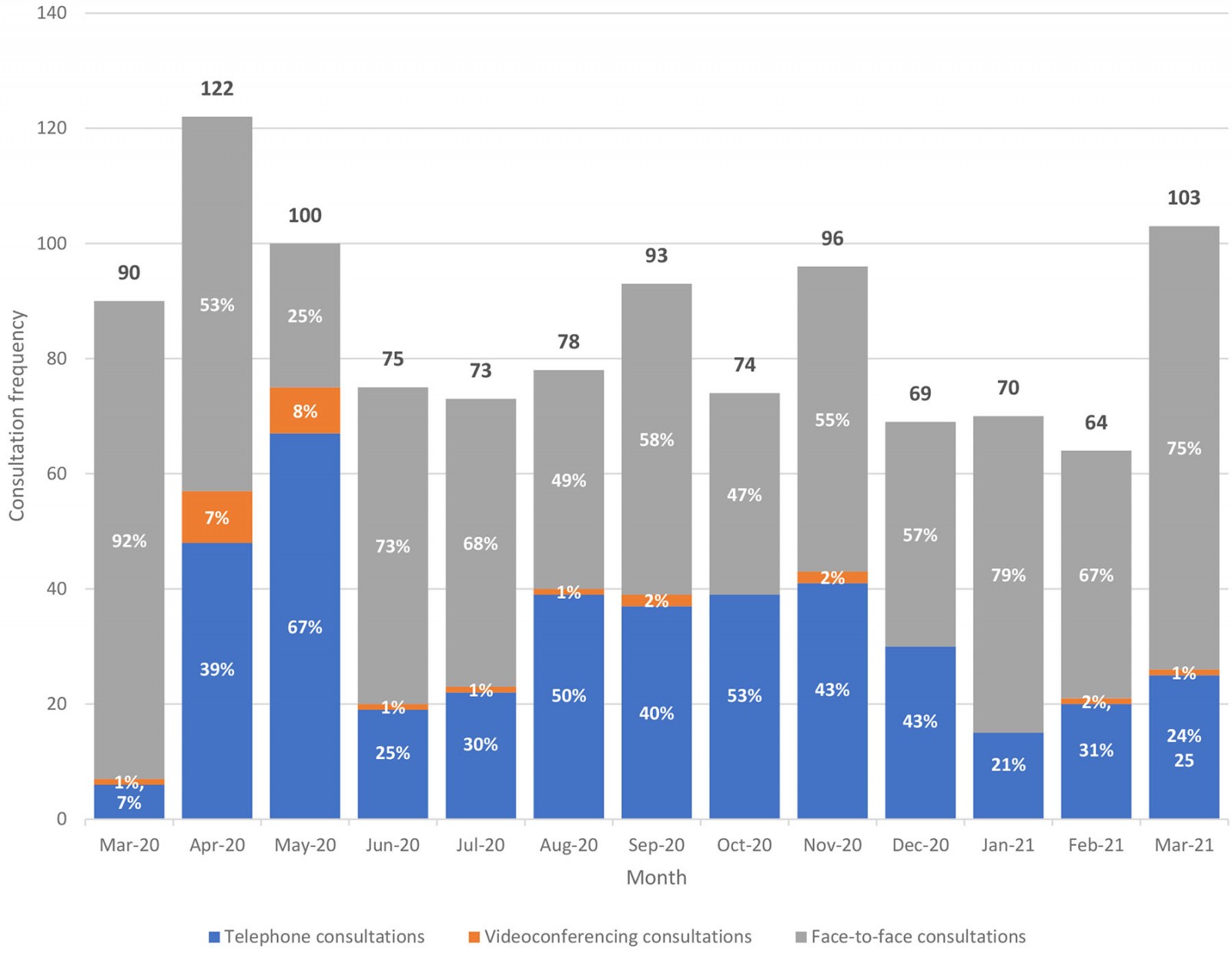

Utilisation of telehealth consultations peaked in May 2020, when 75% (n=75) of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander client consultations (n=100) were delivered using either telephone or videoconferencing (Fig1), aligning with the Victorian statewide COVID-19 lockdown during this period. From June 2020 to March 2021, the proportion of telehealth consultations fluctuated, ranging from 25% to 53% of total consultations delivered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients.

A greater uptake of telephone consultations when compared to videoconferencing was supported by results in the qualitative theme ‘client utilisation of telehealth services’. Health service personnel identified that the uptake of telehealth in general was slow in the first few weeks of implementation due to a general fear in the community pertaining to COVID-19 at this time, and gradually increased in subsequent weeks. The uptake of telehealth was attributed to the ability for clients and health service personnel to quickly adapt to lockdown conditions and changes in health service delivery:

So, I think that it’s been quite a progression because when it [COVID-19] first started it was like, services dropped off, nobody wanted to come and see us, they were quite scared. No one really used, well telephones, but not for that sort of communication … but I think everyone uses it [telephone] for everything now, and everyone is actually quite comfortable and it’s becoming a bit of the norm. (Health service personnel)

From the perspectives of health service personnel, salient barriers experienced by clients to accessing videoconferencing led to a greater uptake of telephone consultations. These included poor internet availability or accessibility, financial barriers (eg no phone credit or data) and low technology literacy. These barriers were expanded on by clients to a perceived lack of compatible technology with videoconferencing platforms and the absence of support to use platforms when at home:

I wouldn’t have a clue how to do that [use videoconferencing platform] on my end … It’s just as easy to talk. I wouldn’t know which button to push, I would push the wrong button. (Client)

With the necessary supports and technology in place, some clients were receptive to using videoconferencing to speak with a GP or a practice nurse. One client shared that they used videoconferencing at the ACCHO for a specialist appointment and were supported by health service personnel to do this.

Table 2: Characteristics of telephone and videoconference consultations

Figure 2: Percentages of telephone, videoconferencing and face-to-face consultations.

Figure 2: Percentages of telephone, videoconferencing and face-to-face consultations.

2. Maintaining the delivery of ACCHO services during COVID-19

Telehealth services were accessed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients across the lifespan, with a median age of 41 years (interquartile range (IQR) 23) for patients using telephone, and 48 years (IQR 20) for patients using videoconferencing (Table 2). When age was analysed as a categorical variable, the highest proportion of telehealth consultations was for those aged between 50 and 54 years (n=73, 17% of total telehealth consultations), followed by those aged between 45 and 49 years (n=52, 12% of total telehealth consultations). Utilisation of telephone consultations was relatively evenly divided between males and females (47% male (n=192), 53% female (n=216)), while males accessed the majority of videoconference consultations (59% males (n=16), 41% females (n=11)).

The qualitative themes ‘acceptability of telehealth consultations’ and ‘preference for face-to-face consultations’ expanded upon the concept of maintaining the delivery of ACCHO services during COVID-19 using telehealth. Generally, telehealth consultations were acceptable to clients; however, there was an overwhelming preference for face-to-face consultations from the perspective of clients and health service personnel. Reasons for this included face-to-face being more personal and aligning with cultural ways of doing, being able to undertake a thorough clinical assessment, and being able to socialise with health service personnel and other community members at the ACCHO. Despite this preference, clients identified that telephone consultations were useful for sharing health concerns with a GP or practice nurse and for receiving reassurance, arranging medication prescriptions, reducing travel time to the ACCHO, and for generally feeling connected to health service personnel during COVID-19.

And now more if I just need like a prescription or something like that, something quick, I just do the telehealth appointments over the phone … if I need new scripts. [Name of nurse] made me an appointment last week and the doctor rang me in the morning and that was easy, because I don’t have to go out of town … (Client)

From the perspective of health service personnel, telehealth consultations were a useful tool to deliver health care, and complemented face-to-face care rather than replaced it. Of total telehealth consultations, the majority were delivered by a GP (93% of telephone consultations (n=379) and 89% of videoconferencing consultations (n=24)), with the remainder delivered by practice nurses and other medical specialists (non-GP medical officers and obstetricians). The most frequently utilised MBS item numbers were for a GP consultation lasting less than 20 minutes (91809; n=264, 61%), followed by a GP consultation lasting at least 20 minutes (91810; n=61, 14%). From the perspectives of health service personnel, telehealth consultations were identified to be most appropriate for GP consultations providing medication prescriptions, delivering health care to clients in correctional facilities, and to clients where there was a pre-existing clinical relationship, to maintain continuity of care.

As telephone consultations were used more frequently than videoconferencing consultations, key challenges were reported by health service personnel. These included the need to rely on listening to clients rather than observing non-verbal cues, the inability to conduct a visual clinical assessment (eg assessment of work of breathing), difficulty managing mental health concerns and associated risks, having clients distracted while on the phone (eg either by family members or by being in a public space), and the difficulty ascertaining client understanding of information provided:

You get so much more information from sitting in the same room as someone and seeing what they look like, how they present themselves because that can, you ask a question and a person’s body language changes, their voice may say the same stuff, but you might see something else shift that leads you down to think, then ask a different line of questioning and that leads to the actual problem that they may be, were a bit hesitant in talking about. I don’t think anything can replace face to face interactions with clients. (Health service personnel)

Despite these challenges, telehealth services were accessed by clients who were geographically dispersed in the Northern Grampians and Ararat regions, with the highest proportion of consultations delivered to those residing in Ararat and surrounding areas, and Stawell (45% (n=194) and 27% (n=119), respectively), followed by Halls Gap and surrounding areas (14%, n=59) (Fig3). Further, 77% (n=337) of consultations were delivered to clients residing in areas experiencing high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage and low levels of advantage, indicated by either being postcodes in a first or second IRSAD decile16. Included postcodes ranged from being in the first IRSAD decile to the ninth IRSAD decile.

Figure 3: Telehealth consultations by postcode.

Figure 3: Telehealth consultations by postcode.

3. Implications for sustaining telehealth in an ACCHO

Although the delivery of telehealth services as a proportion of total ACCHO clinical services varied monthly between March 2020 and March 2021 (Fig2), support for the continuation of telehealth was provided by interview participants. The qualitative theme ‘future of telehealth’ identified key implications for sustaining telehealth at the ACCHO. Health service personnel identified that the ACCHO had the necessary infrastructure and capacity to continue implementing telehealth services to clients as initial teething issues had been addressed (eg setting up telehealth platform, purchasing webcams, educating clients). From the perspectives of clients and health service personnel, support for the continuation of telehealth was provided due to perceived benefits (eg convenience, reduction in travel, improving access to GPs and health service personnel, overcoming transport issues, ability to attract additional MBS revenue) when used in the appropriate context despite limitations (eg less personal than face-to-face consultations). Health service personnel acknowledged that sustaining telehealth was largely dependent on government policy and the maintenance of the MBS telehealth items, which were temporary at the time of undertaking the study. At a local level, implementing education and technological support was vital to encouraging greater use of videoconferencing consultations; however, clients were generally satisfied with using telephone consultations in addition to face-to-face consultations where needed:

… it’s probably the only thing that telehealth is not personal and you do sort of hold back a few things because you can’t actually, like I’ve got a blown up knee, you can’t actually show them how much you can move or flex, they just ask is it sore. Well that’s the reason I rang because it is sore … you can’t, but in saying that, I’ve just said to them [ACCHO health service personnel], and they’ve said to me a few times, it sounds like you do have to come in and see us and I’ve gone in and seen them. (Client)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the implementation of telehealth services for primary healthcare delivery in a rural ACCHO (MM 5–small rural town). Qualitative findings expand on other research examining the implementation of telehealth within a Victorian ACCHO (MM 2–regional centre) during COVID-19, which found that telehealth was an important adjunct to the delivery of holistic primary care services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients13.

Over the study period there was a greater uptake of telephone consultations relative to videoconferencing consultations, utilisation of telehealth services across the lifespan, and frequent use of telehealth for the delivery of short GP consultations (either less than or at least 20 minutes). Although the utilisation of telehealth services as a proportion of all services delivered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients fluctuated monthly, telehealth services became embedded as a new mode of primary healthcare delivery over the 1-year period and, notably, between COVID-19 lockdowns. Further, telehealth services were acceptable to health service personnel and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients despite a general preference for face-to-face consultations. Sustaining telehealth was identified to depend largely on government policy and the maintenance of the MBS telehealth item numbers.

Findings illustrate the responsiveness of a rural ACCHO in rapidly adopting telehealth during COVID-19 to continue delivering primary healthcare services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients. This rapid adoption of telehealth was also observed in primary care organisations across Australia and internationally2,27. Responding to the healthcare needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is an identified strength of ACCHOs28,29. Another example of responsiveness demonstrated by ACCHOs during the early phase of COVID-19 was the culturally appropriate communication of health messages to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples30.

These findings are consistent with an analysis of national data that identified a strong preference for GP-delivered telephone consultations, and an apparent under-utilisation of GP videoconferencing consultations in the general population27. Understanding the preference for telephone consultations and barriers to the utilisation of videoconferencing is an important area for future research examining the equity of telehealth delivery, both for the general population and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, particularly given the preference of policymakers for videoconferencing27. This study provides some insights as to why there may be an under-utilisation of videoconferencing in a rural ACCHO from the perspectives of health service personnel and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients (eg access and availability of technology and internet, financial barriers, low technology literacy).

Further, this study addresses the need to examine the acceptability of telehealth and utilisation of telephone consultations by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients through qualitative research – a need identified by a previous literature review11. Despite a preference for face-to-face consultations, clients were appreciative of having access to ACCHO health service personnel with whom they had a pre-existing relationship through telehealth services during COVID-19 and identified other benefits of telehealth consultations (eg saving travel time, arranging medication prescriptions). Health service personnel also found telehealth acceptable when used in the appropriate clinical context. This resonates with other qualitative research undertaken in the Australian primary care setting during COVID-19 that identified similar benefits and challenges of telehealth, finding that GPs thought telehealth should complement rather than replace face-to-face care31.

Translation and implementation

The preference of policymakers for videoconferencing consultations, reflected in the 2021 amendments to telehealth MBS item numbers for GPs that removed item numbers frequently utilised by GPs at BBAC (MBS item number 91809 and 91810)3, does not align with the needs and preferences of the ACCHO and their clients identified in this study. In Victoria, the Western Victoria Primary Health Network and collaborating ACCHOs advocated to the Department of Health to restore these MBS item numbers. They shared preliminary findings from this evaluation in a letter around the delivery of telehealth services to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander clients residing in rural postcodes known to have high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage and low levels of advantage. It is also likely that these clients already experience other known barriers to accessing primary healthcare services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (eg transport, financial)32,33.

Strengths, limitations and future research

Limitations of this study include reliance on the provided health-service-level consultation data, rather than on client-level data, and the inability to extrapolate findings to other variables (eg area-level socioeconomic status at the appropriate scale, which is currently limited to postcodes). Further, the qualitative sample and subsequently the data collected depended on relationships established with health service personnel and clients. Due to this, there is a potential that this study captured data from clients who were more engaged with the ACCHO and telehealth services. Future research should expand upon this study and examine the perspectives and experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in accessing telehealth services across other ACCHOs, geographical and clinical settings, in addition to the experiences of health professionals in delivering health care through telehealth across other settings.

A strength of this study is the evaluation of telehealth using a mixed-methods approach and in partnership with a rural ACCHO for the purpose of identifying opportunities to improve the delivery of primary healthcare services. This work contributes to furthering the evidence base around models of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples residing in rural areas – a need identified by a previous review33. With the extension of the MBS telehealth items, it is recommended that policymakers engage with the ACCHO sector, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders, to understand the experience of other communities in implementing telehealth services17.

Conclusion

This study provides mixed-methods findings around the first year of implementing telehealth services for the delivery of primary care by a rural ACCHO. A greater uptake of telephone consultations rather than videoconferencing, and frequent use of short GP consultations delivered by telephone, were key findings of the study and consistent with a larger national investigation. Reasons for this were largely related to technology and infrastructure. Generally, telehealth was acceptable to both health service personnel and clients, with benefits and challenges identified. Telehealth provided a useful adjunct to face-to-face consultations when used in the appropriate context. Future research should examine these benefits and challenges in other ACCHOs, particularly in rural areas. Engagement of the ACCHO sector in the policy discourse around telehealth going forward is important to ensure localised responsiveness to the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is supported at a national level.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our colleagues at Budja Budja Aboriginal Co-operative who supported the study – including Chief Executive Officer and Djab Wurrung Elder, Tim Chatfield; Co-operative Services Consultant, Roman Zwolak; Clinic Manager, Dianne Martin; Administration Support, Alison Chatfield; and Mobile Clinic Coordinator and Social and Emotional Wellbeing Coordinator, Sarah Garton.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Western Alliance Academic Health Science Centre as part of the COVID-19 grants. HB, FM, AWS, KM and VLV are supported by the Rural Health Multi-Disciplinary Training Program funded by the Australian Government. VLV is the Academic Advisor (Research and Clinical Training) at BBAC – an unpaid role (budjabudjacoop.org.au/new-mobile-clinical-health-van-april-2019). FM is an Associate Research Fellow with Deakin Rural Health – a position funded by the research grant supporting this study. JAC is supported by the First Peoples Health Unit, Faculty of Health, Griffith University.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The data generated and analysed in this study are not publicly available as participants consented to their data being used only for the purposes described in this study.

References

You might also be interested in:

2016 - Household structure, maternal characteristics and childhood mortality in rural sub-Saharan Africa