Introduction

In Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ), all-cause and amenable mortality rates are higher in rural than in urban areas, an effect that is accentuated for Māori (the Indigenous people of New Zealand)1. The extent of these disparities has only recently come to light with the development of NZ’s first purpose-built urban rural health classification, the Geographic Classification for Health2. It is estimated that around 19% of New Zealanders rely on rural health services and around 10–15% on rural hospitals for health care3,4.

Internationally, in high-income countries, rural hospitals have been recognised as important healthcare providers, improving access to and integration of health services for rural communities5,6. However, rural hospital definitions and nomenclature vary widely across different jurisdictions5-8.

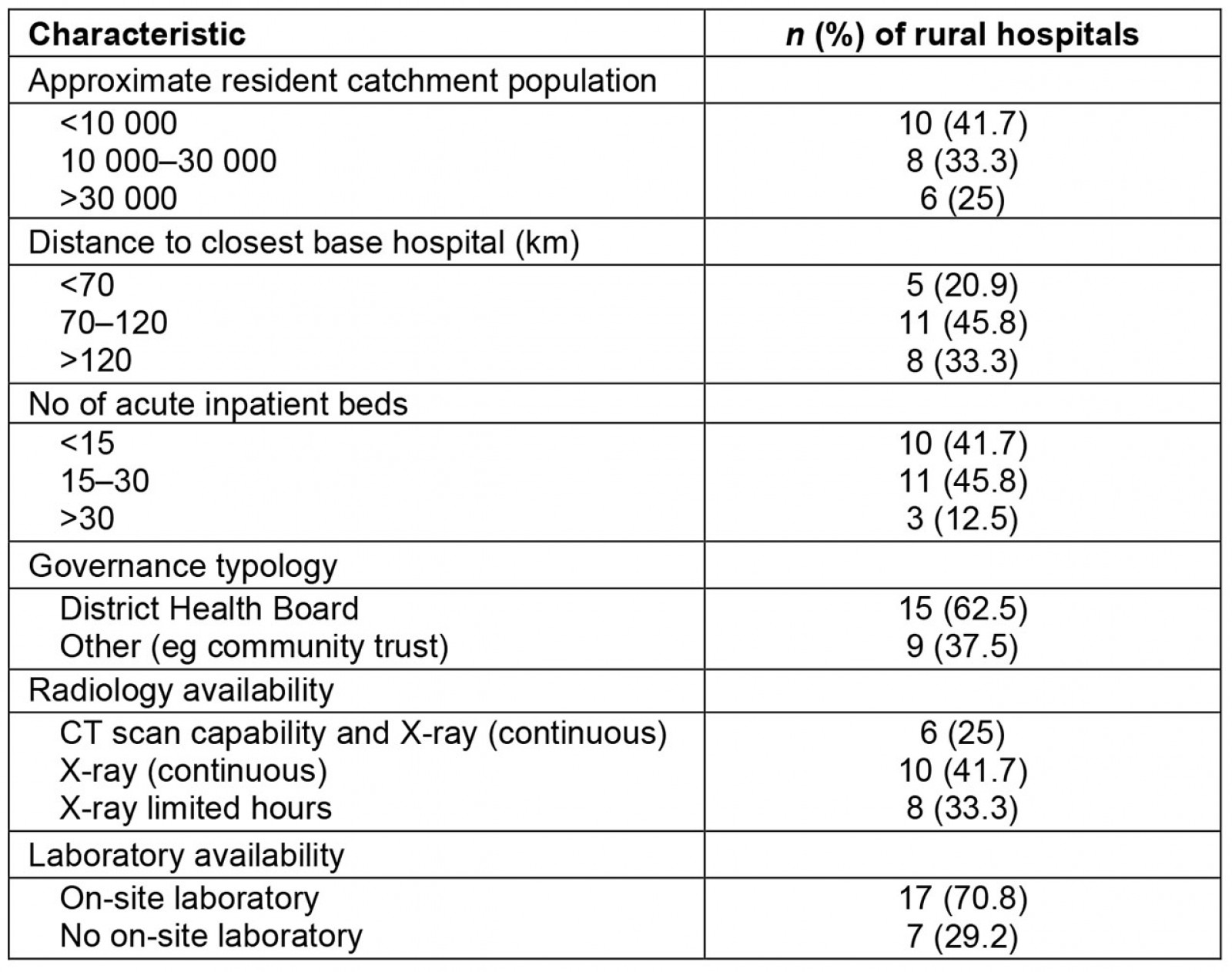

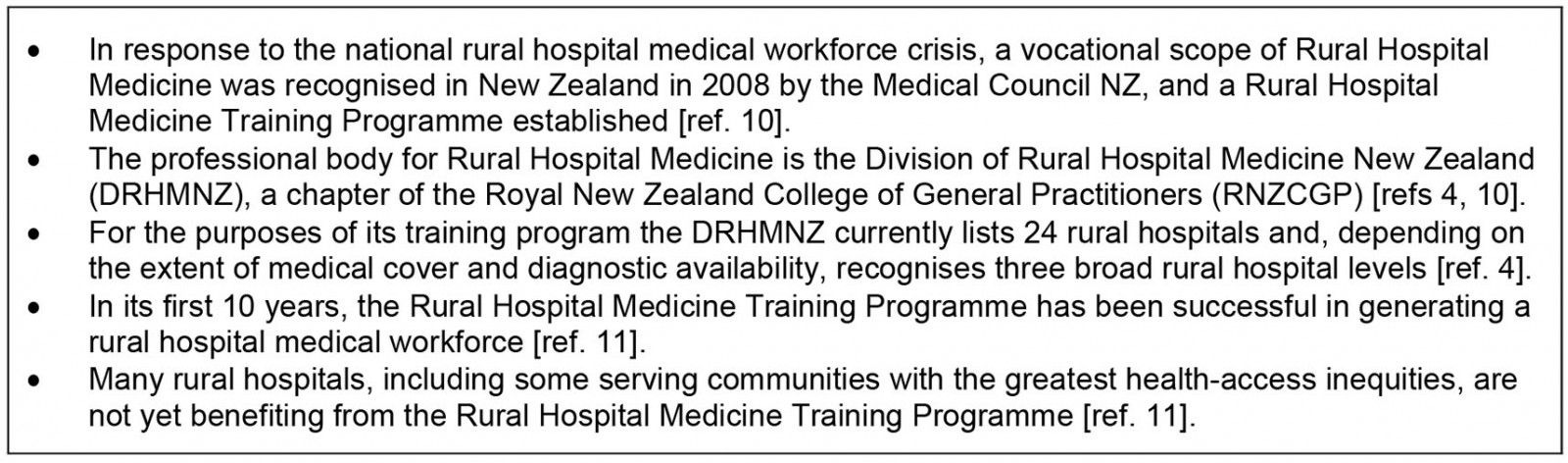

In NZ, there is no national policy for rural hospitals9. The defining features of rural hospitals accepted by the Medical Council of New Zealand and the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners’ Division of Rural Hospital Medicine (DRHMNZ) (Box 1)10,11 are geographical distance from specialist services, acute inpatient bed capacity, continuous acute care and a predominantly generalist workforce. The DRHMNZ list of rural hospitals currently sits at 24 (Webber J., pers. comm., 2021). These rural hospitals sit along a broad spectrum; at one end are small (<15 beds) hospitals integrated with a primary-care service, and at the other are larger (>30 beds) hospitals providing secondary care services separate from primary care, often with advanced diagnostics and providing some surgical and anaesthetic services. In addition, NZ rural hospitals differ in their distance from city hospitals and their governance typologies (Table 1).

There is a lack of knowledge of the place and contribution of rural hospitals in NZ’s health system (Box 212-17)9,18. Much of the existing NZ rural hospital literature is now more than a decade old 3,15,19. The extent to which rural hospitals improve access to health care, improve health outcomes and improve health equity for NZ rural communities, particularly for Māori, is also unknown. This article forms part of a larger exploratory study conducted in 2021 using both a questionnaire survey and semi-structured interviews20. The aim of this study was to explore the place of rural hospitals in the NZ health system from the perspective of people in rural hospital leadership roles.

Table 1: Characteristics of rural hospitals in Aotearoa New Zealand (n=24)

Box 1: The Division of Rural Hospital Medicine New Zealand and its Rural Hospital Medicine Training Programme10,11.

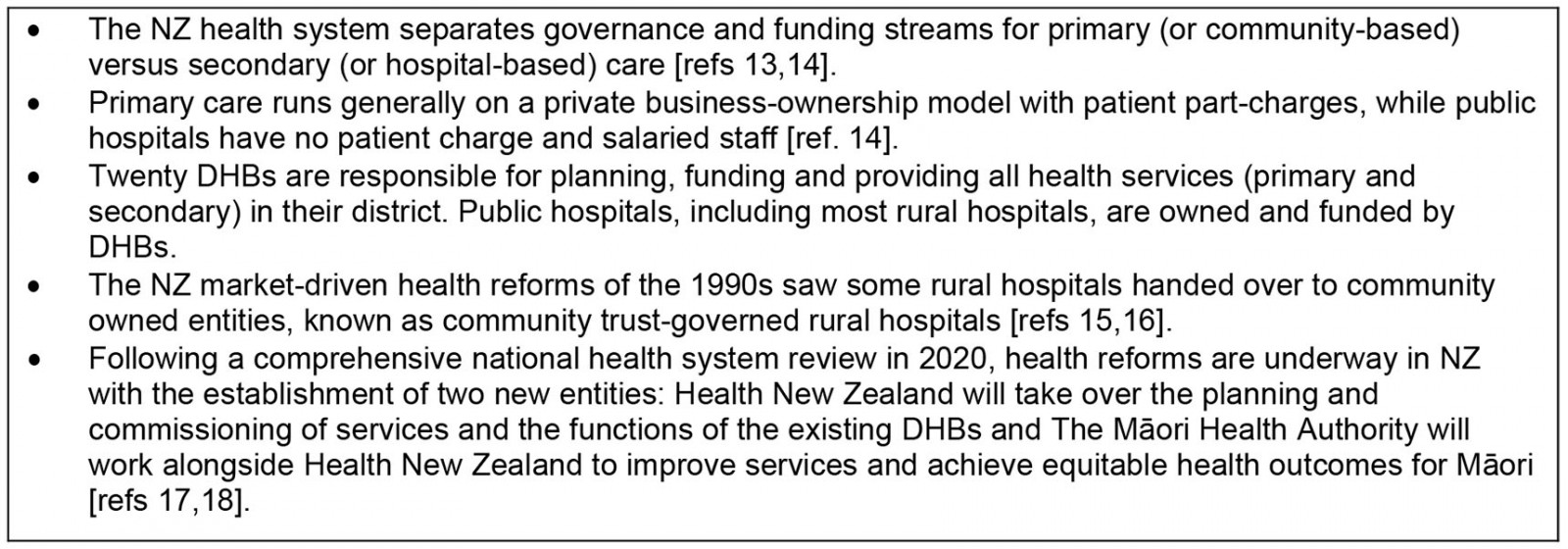

Box 2: Overview of the health system in Aotearoa New Zealand12-17.

Methods

This qualitative study used a framework-guided rapid analysis method.

Participants

Sampling was purposive with the aim of recruiting participants in leadership roles (management and/or governance) at each rural hospital, including Māori leadership and the leadership of national rural health key stakeholder organisations: the New Zealand Rural Hospital Network (NZRHN)21, DRHMNZ4, the Rural General Practice Network22, and the Rural Health Alliance Aotearoa New Zealand23.

All 24 rural hospitals recognised by the DRHMNZ were invited to participate in the study. Participants were invited to participate by email from April 2021 with the invitation also posted on the NZRHN website. Access was facilitated through four of the authors (KB, RA GN, RM) being known to participants through regional and national rural hospital networks.

Those rural hospital and stakeholder organisation representatives who had not provided a response within a month were contacted again by email with a further invitation to participate. A final email invitation to participate was sent in early September 2021.

Demographic information was collected from participants during the consent process using an online questionnaire generated by Qualtrics (2021) (https://www.qualtrics.com).

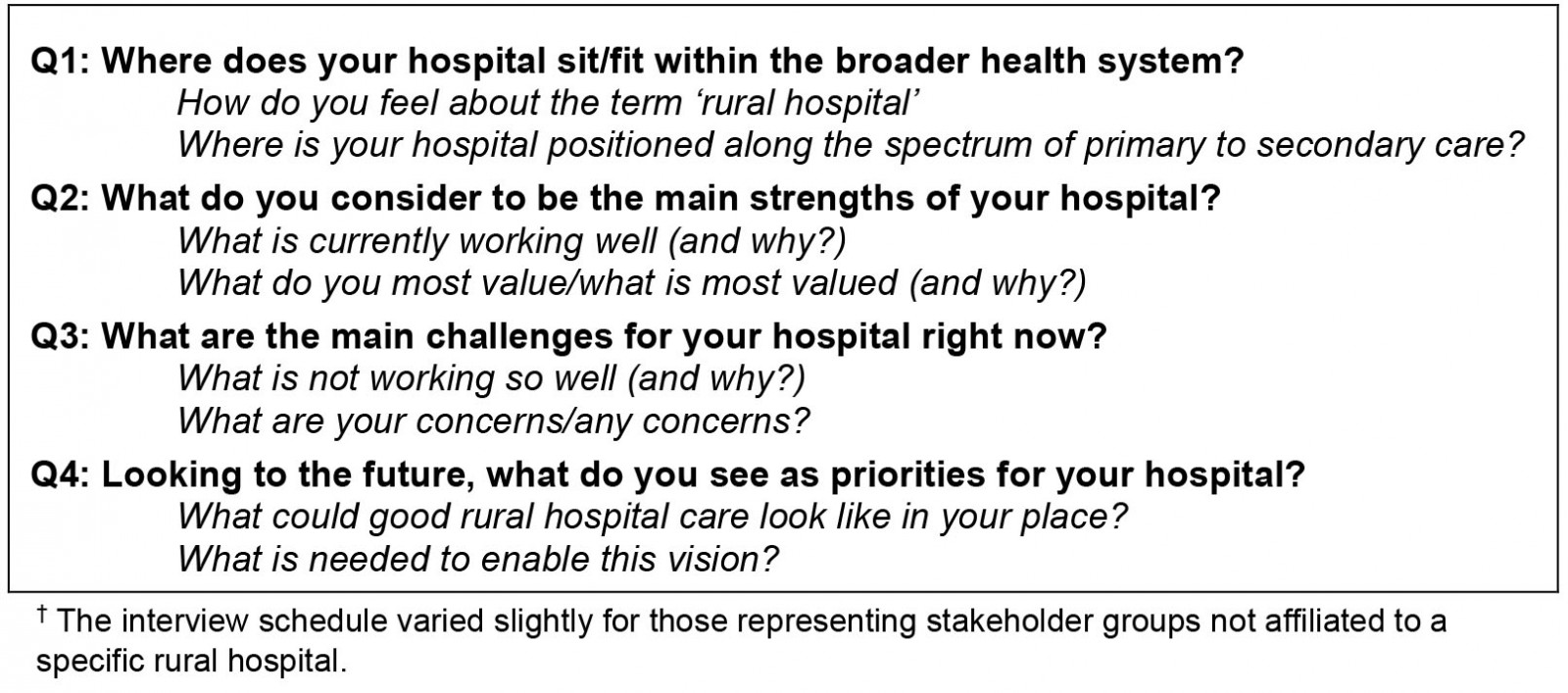

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken via Zoom video-conferencing between April and September 2021. At the start of each interview with rural hospital leaders, key characteristics of the rural hospital represented were checked with the interviewee. The interview schedule, developed by the research team, explored three broad areas: the context within which health care is delivered; what is currently working well and what is not, and what good rural hospital care would look like for the participant (Supplementary table 1). The interview schedule varied slightly for those representing stakeholder groups that were not affiliated to a specific rural hospital. After the first three interviews the schedule was reviewed and minor modifications were made to ensure a more natural flow (ie a conversational approach), according to researchers’ feedback.

All interviews were conducted by members of the research team (LC, TS, KB) with experience in qualitative research. Most were individual interviews; one interview involved two interviewees from a single organisation. Interview duration was 21–44 minutes (average length 32 minutes). Interviews were recorded and transcribed using Zoom’s inbuilt auto-transcription service. At the completion of each interview the interviewer made notes, listened to the recording and checked the accuracy of the automatic transcription. The interviewer then generated a summary (memo) for each interview transcript.

Analysis

Thematic analysis was undertaken using a framework-guided rapid analysis method24,25. A structured template was developed (KB, LC, TS), which was used to categorise data according to each topic in the interview schedule. Interview memos and templates were all reviewed by at least two team members. Halfway through data collection, team members (KB, LC, TS, GN) met in person to review summary responses and templates and to discuss and ensure team agreement on identified themes. Further analysis was undertaken (KB, LR, TS, LC), with team collaborative discussions to refine themes and the relationships between them.

Researcher positionality

Given the small community of rural academics in NZ, it is likely that some researchers were known to some of the participants. Several researchers are also practising medical clinicians in rural hospitals (KB, GN, RM). The lead interviewer (LC) and senior researchers assisting with analysis (TS, LR) were not known to participants.

Measures taken for ensuring rigor in this context included explicitly acknowledging (through the ethics approval process) the insider status of researchers in all participant information and consent forms, team member review of data collection and regular team discussion during the analysis phase, including the participation of TS and LR, who are not rural clinicians. Insider positionality also brought advantages in this study as it allowed awareness of key issues with the research term versed in the reality of the study context26.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (D21/009).

Results

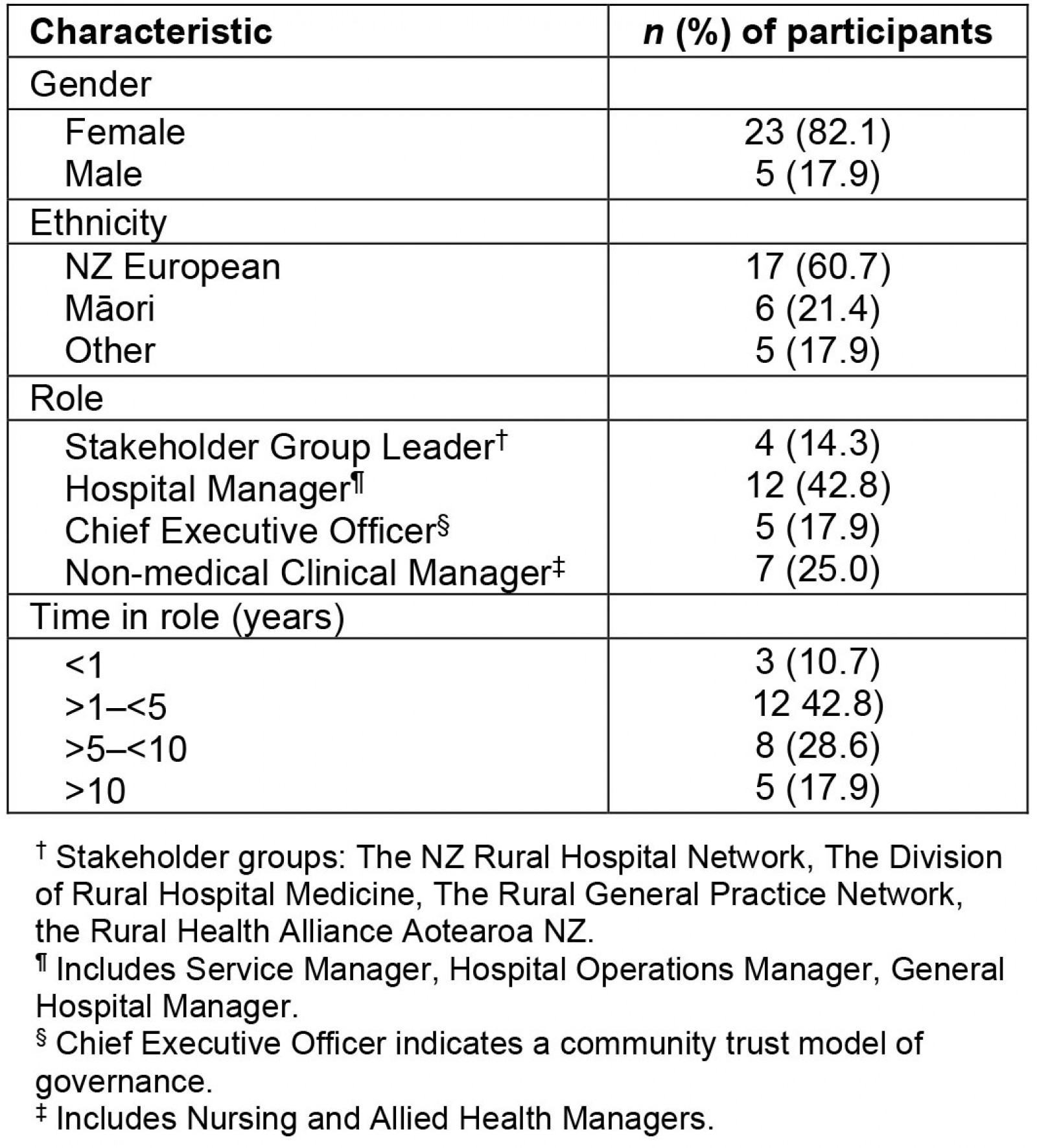

Twenty-seven interviews (28 participants) were conducted, representing four stakeholder organisations and 22 rural hospitals. Three participants represented more than one rural hospital. Four rural hospitals were represented by two participants. Six participants identified as Māori. Of the 22 hospitals represented, 13 were North Island-based and nine South Island-based. There was no response from the remaining two hospitals. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Two main themes explained how participants perceived the place of rural hospitals in the health system: ‘Our place and our people’ reflected the local, on-the-ground situation, while ‘Our positioning in the wider health system’ related to the external environment rural hospitals work within. These two themes and their subthemes are described. Illustrative participant interview quotes (P1–P28) are presented.

Table 2: Interview participant characteristics (n=28)

Theme 1. ‘Our place and our people’

It [the term ‘rural hospital’] puts a line in the sand, as to the locality, and needs of a rural hospital, and how different that is compared to urban environments … you know the needs of those communities and having a hospital situated in that community … that term ‘rural’ indicates a level of additional resources required to actually provide a service like that. (P19)

Most participants expressed confidence in their ‘rural hospital’ identity and felt the term reflected their context while also giving a clear point of difference from both community-based rural health services and non-rural hospitals.

The hospital building itself held a sense of permanence, was often a source of pride and provided easy navigation for the community:

The physical locality of a hospital gives confidence. (P27)

Our geographical isolation:

Overwhelmingly transport, transport, transport, in relation to accessing health services … that is the rural conundrum, aye? Absolutely, the single biggest issue, constant and barrier. (P25)

Local health system responses were largely determined by spatial isolation from urban centres and comprehensive specialist health services. Long travel distances (often aligned with poor roading infrastructure and lack of public transport) affected access to healthcare for communities.

While technological advances could bridge distance to some extent, poor digital connectivity with patchy telephone and internet networks remained a significant issue for some rural hospitals, particularly those that were more geographically remote.

Our community connectedness:

The strength of our hospital is the sense of community … the hospital has always been seen as central, core … to the community. And this community in years gone by, have invested heavily in our hospital when it was owned at a local level and people have long memories around that. (P21)

Across all governance typologies there was a strong sense of community connection with rural hospitals being tightly linked with the place, the people and the history. This connection meant an awareness of specific health needs and the ability to provide appropriate and relevant services.

Addressing the social determinants of health, through strong linkages to other organisations, frequently featured in rural hospitals’ approaches. By providing employment and educational opportunities, rural hospitals also had wider local economic benefits.

Participants representing small community-trust-run hospitals (one governance typology) tended to have the strongest sense of embeddedness within a community. Here, the hospital, seen as an extension of the community, ran in accordance with community needs:

As locals, tangata whenua [local indigenous people, NZ Māori] can respond flexibly to local people’s needs. The staff are from this area, so the patients know our staff and our staff know our patients, our service is based on our knowledge of each other. (P6)

Our role, what we do:

We are providing the care that our community needs to the level that we can, at the top of the scope of our practitioners, so that our patients don’t have to leave our community for care if they don’t have to. (P10)

Participants explained how having a hospital facility that is open continuously meant people could stay closer to home for a wider range of care. Having a hospital facility also supported the rural hospital’s community-based health services.

The rural hospital provided a safety net and acted as a conduit between community-based care and the long distance to base or tertiary hospital care. The provision of ‘round the clock’ acute or urgent care (managing any emergencies, at least initially, including transfer if escalation of care was indicated) was fundamental for a rural hospital service:

You jolly well need to know that those hospitals are there. You don’t necessarily need them to be able to meet your every need, but you need access to the urgent care. (P20)

Being a ‘hospital’ gave a degree of authority at the interface with the wider health system, particularly the ability to admit patients locally, and to facilitate access to transfer to specialist care.

Where we sit on the primary–secondary care spectrum:

I tend not to think of us as a primary or secondary service. I think of us as a rural health service. A hybrid of primary and secondary and what we try and do is really focus on the continuum of care for people. (P16)

Many participants struggled with positioning their rural hospital in either the primary or secondary care categories. Boundaries between primary and secondary care, which generally made sense in an urban setting, blurred in a rural context, particularly in smaller rural hospitals:

Well, we’re not quite secondary (care) but we’re above primary (care) so we’re sort of, yeah in the middle, somewhere. Sometimes we do things that are probably quite close to secondary care and sometimes we’re doing things which are probably primary care so somewhere along that line, and I think there’s a shifting line. (P5)

Most of the larger rural hospitals, however, saw themselves very much as providing rural secondary care, rather than primary care.

Our staff: Small teams, broad scopes:

Staff are the absolute strength and they work well together in a very strong, cohesive team in a small standalone place that’s a long way from base hospital support. Anything can happen, and you just have to respond ... you really are dependent on each other, and there has to be enough staff there that you can respond safely to whatever happens. That is a hard concept for people at a distance to understand. (P8)

Accounts were given of close-knit, flexible and adaptable clinical teams working across broad scopes covering areas such as the emergency room, walk-ins, inpatients and escorting interhospital transfers. While many participants discussed their rural hospital’s vulnerability in emergency situations, they also reported resilience:

We are used to when things fall over, we have to cope. Because the response and support [from outside] is not immediate … so we’re used to survival mode. (P21)

The challenge of attracting and keeping clinical staff was discussed by all participants:

A workforce is hugely important and can’t be underestimated, you can talk about all these wonderful things around how we might work in an integrated way, but if you don’t have a workforce that supports that then you’re not going to get very far. (P23)

Participants described chronic staff shortages, constantly having to juggle rosters to accommodate leave, sickness or when staff were pulled away for patient transfers or training. While fostering a culture of learning was seen as an important workforce strategy, ‘keeping up’ with training and accreditation standards across broad scopes, particularly in light of staff shortages, was difficult:

Pretty tricky, to ensure that everyone is skilled at and competent at things, you know you might not see a paediatric patient for a while and then all of a sudden, you’re faced with it. (P1)

In addition, participants conveyed how required training was often of questionable relevance to rural teams as it did not take into consideration the broad scope of clinical practice in the rural context. For some rural hospitals, the DRHMNZ’s national Rural Hospital Medicine Training Programme was providing a solution for medical workforce shortages. For others, this training program had not yet made an impact. Some saw value in the program but had been unable to attract Rural Hospital Medicine specialists or trainees.

Theme 2. ‘Our positioning in the wider health system’

When systems fall over, when we have run out of staff, when we can’t get ambulances, we really don’t have much support from the wider tertiary centre. We still have policies and procedures coming out aimed at the tertiary centre that don’t reflect rural. (P21)

Participants reported poor understanding of the rural context by centralised bodies and institutions and often felt stymied by things out of their local control. National and regional health policy, funding and regulatory systems were seen as misaligned, having been set up without input or collaboration from rural hospitals and rural health services. It was, therefore, difficult for rural hospitals to work within these structures and they were often left feeling invisible.

Our funding perceptions: at the end of the dripline:

[as] a rural hospital, you might as well consider yourself a bottom feeder in the sea of DHB [District Health Board] funding. (P20)

Perceived funding inequities were mentioned by almost all participants, regardless of the rural hospital’s governance typology. Issues raised included lack of autonomy over use of allocated funding; fragmented funding, which assumed an urban-centric model of separated primary and secondary services; and uncertainty of continuing funding.

The more distant from urban centres, the smaller the population and rural facility, the more it made sense to provide co-located and integrated care. However, neither terminology, regulatory environment (including workforce) nor resources were well aligned with this way of working. Participants representing smaller rural hospitals with primary and secondary care co-located but funded separately felt caught between the economic interests of these two levels.

Our urgent and emergency services, ‘cobbled together’ (P13):

So, we’re not an emergency service, we’re not allowed to call ourselves an emergency service, as there are other criteria that you have to meet for that. But we are … well, we do have those presentations that are emergencies … (P1)

While rural hospitals all provided continuous emergency care, the terminology, service configuration and subsequent resource varied widely. Participants perceived a lack of any clear and consistent national planning for rural after-hours and emergency care, which was often based on historical arrangements. Some rural hospitals had a recognised emergency department, but others did not. Some provided after-hours ‘urgent care’ through a primary-care-funded service incurring costs to patients that participants perceived as inequitable for their communities:

Urgent care service funding ...we’re sort of a ‘satellite emergency department’, we see everything … we manage, stabilise, transfer and have really good relationships [with base hospital], but the thing is, those [satellite emergency department] patients can be charged and that’s really not consistent with what would happen if it were an ED … so there are inequities there. (P17)

Our relationship with the District Health Board – ‘we’re a constant after-thought’ (P27):

We have to beat the drum regularly, so they don’t forget about the rural hospitals. (P14)

Support from District Health Boards (DHBs) (Box 1) for their rural hospitals varied widely. Regardless of rural hospital size or typology, DHBs were seen by participants as urban-centric, their focus on secondary and tertiary hospital specialist care, with rural hospitals out at the edges.

A DHB’s understanding of the rural hospital context was crucial to providing rural hospitals with effective support, and participants were aware of the need to continually invest in the relationship. The few participants who felt well supported by their DHB described good communication channels, reciprocal engagement and the ability to maintain local autonomy (eg adapting policy and procedures to the local context), which facilitated local operational decision making:

The fact that we are part of a DHB, we have an anchor into a system that’s quite robust. But we’re also physically removed from that and I think that creates a level of opportunity for us. We’re a smaller team, so our ability to have local conversations and make adjustments is much easier. But still having that kind of ‘tailor-back into our home base’ which affords a whole round of resourcing, expertise and support that’s available for us. (P3)

However, understanding of local context and effective support and resource was often lacking. Participants gave accounts of being brought into discussions concerning their rural hospital once decisions had already been made, expressing frustration in ‘being foiled by the decisions in base hospital (P8)’ and around the frequent lack of local consultation.

In some cases, ineffective or absent engagement of DHBs with their rural hospitals led to a downward spiral, leaving a rural hospital feeling disempowered:

When you don’t have a strong DHB partnership, no matter what structure you’ve got, unless you still maintain that partnership model with the funder or the DHB … they just let the rural sites either decay, underfund them or um, you know, ‘it’s out of sight’ so you don’t have to think about them. (P25)

Feeling undervalued:

[There] seems to be a real failure to see what the benefit of having good [rural hospital] services in communities is and how that reduces the impact on secondary services, as well as ensuring that people just get better care. (P13)

Participants felt their rural hospitals were undervalued by the centralised, urban-based organisations they were dependent on. This feeling was further exacerbated at an individual level by participants’ regular encounters of negative perceptions of rural hospital services from city-based colleagues:

[A rural hospital] is not just a little box out in the country somewhere, which is what a lot of city folk think … they think that rural hospitals don’t perform, they don’t [provide] good care and they can’t do things. (P5)

For many participants this negative ‘outsider’ perception was at least partially due to the absence of strong cohesive national advocacy for rural hospitals:

Our ability to have one strong, united voice is probably compromised … you know, policymakers and people who are making decisions have to come to ten different factions within. How do we advocate for rural health and not be precious about us [as one rural hospital] having our spot in the limelight? (P3)

With poor support and no clear expectations about how their services should look, much of a rural hospital’s focus was reactive, defending and keeping their particular corner afloat. With a wide range of facilities falling under the ‘rural hospital’ umbrella, the lack of a nationally accepted definition of ‘rural hospital’ was seen by many as problematic:

[there is a] huge variation in care [across rural hospitals] and in patient and health system expectations, because we’re not saying: ‘this is what you should have in a town, this is what the basic minimum should be’. (P4)

Discussion

Summary of main findings

Through interviews with rural hospital leaders from across NZ, this study updates and furthers understanding of the rural hospital concept. This includes the context in which they operate and the strengths and challenges common to all rural hospitals as well as the large variations between them.

Locally, geographical isolation and community connectedness form a strong rural hospital identity contrasting with rural hospital misalignment and invisibility in the wider external health system environment. Rural hospitals are an integral part of rural health services, providing essential urgent and emergency care, local inpatient care, support for rural community-based health services and facilitating navigation for the community between home, community services and urban hospitals. They are situated on a broad spectrum between primary and secondary care and advocate for better and more joined-up services for their local communities. Small rural hospital teams are adaptable and cover broad practice scopes but, with chronic rural workforce shortages, are also vulnerable.

Nonetheless, rural hospitals operate at the health system periphery, feel neither valued nor well supported by the regulatory environment they are dependent on and are often stymied by fragmented centrally orientated systems, processes and funding models. The lack of a clear nationally accepted definition of a rural hospital was seen as problematic.

Comparison with existing literature

The themes identified in this study resonate with established key rural health concepts and frameworks, including local health responses, broader health systems and power27-29. While a dominant negative view of rural health is challenged by the first theme, it is well illustrated by the second theme with its strong deficit frame30. Findings suggest that better articulation, and consequent wider knowledge and understanding of the rural context, may be key to reducing tensions between these two perspectives.

Access in the spatial sense is recognised as the key rural health issue worldwide31,32. In this study, rural hospital responses were to a large extent determined by geographical isolation from urban centres and specialist services. In accord with other rural health reports, study findings centred on strong rural hospital staff teams and community connections7,33. Findings also confirm the important dual influences of local context and broader health systems factors in shaping rural hospital responses27,34, which concurs with literature suggesting the more geographically remote a rural health service is, the more splintered the urban-centric systems, processes and funding models that the service depends on33,35.

A key function of rural hospitals found in this study was the provision of continuous acute inpatient care for rural communities, consistent with reports from comparable countries5,36,37. Being situated at the interface between primary and secondary care can contribute to integration of service delivery and benefit rural communities5,7. However, as found previously, study participants perceived that external health systems often constrained rather than enabled rural hospital responses8,9. Prior research concurs with study findings that divided funding streams within a health system (as currently exist in NZ) can impact negatively on the delivery of care in rural settings, particularly acute and emergency care5,32,36.

A review of hospitals in rural or remote areas in eight high-income countries noted that common challenges across diverse geographical settings included financial sustainability of services, the provision of emergency care and the provision of timely patient transport to more specialised services5. Only one of the countries reviewed had a national rural hospital policy in place5.

The role of rural hospitals in NZ, as in other countries, is set in the overall context of a national health system and service delivery structure7. Local and national context have driven the way in which different NZ rural hospitals have developed3,15,38 to offer a wide range of facilities and service delivery models and is consistent with research in comparable countries5,7. Study findings further support the idea that rural hospitals are not simply a small version of a large urban hospital, rather they have their own different foundation and purpose focused on their location and the communities they serve, including their cultural and social contexts8,37,39,40.

Implications for policy and practice

NZ rural hospitals sit at the periphery of a compartmentalised health system and provide a broad scope of services across both primary and secondary care to diverse rural communities. As such, alternative rural-centric structures, policies and funding mechanisms are needed to facilitate integrated care at the interface between community and hospital-based care within each locality while also factoring in their spatial isolation from specialist services.

Rural hospitals in NZ vary in size, distance from tertiary services and governance model, and cover a broad range of services. Therefore, policymakers need to be clear about what they mean when referring to rural hospitals. While the idea of a single collective definition for rural hospitals in NZ may be misleading given their inherent diversity, the development of appropriate national policies for rural hospitals is likely to progress their effectiveness in meeting the health needs of rural communities across NZ.

Strengths and limitations

The study involved Māori, the majority of NZ’s rural hospitals, and national rural health organisation representation. The study’s perspective was that of rural hospital leaders who were mainly non-medical, in contrast to recent NZ rural hospital literature, which is largely medically focused9,33,38. The study did not consider community perspectives nor the perspectives of those working in central DHB and other urban settings.

Future research

Further research is needed on the extent to which and how different rural hospitals (and their local health system) work to improve access to health services, integration of health services, health outcomes and health equity for NZ rural communities, particularly for Māori. Further rural hospital research should include community perspectives as stakeholders of interest. Research should be undertaken to define core rural healthcare services in NZ as has been done in comparable countries41.

Conclusion

In capturing a collective national rural hospital leadership voice, this study furthers understanding of the place of rural hospitals in the NZ health system and offers a starting point in considering the varied nature and scope of service provision models that exist under the term ‘rural hospitals’.

Distinguished by their community connectedness and geographical distance from large hospitals and specialist health services, rural hospitals provide services across the primary care–secondary care interface for diverse rural communities, including acute and inpatient care, and play an integrative role in locality service provision.

However, NZ rural hospitals, operating at the periphery of an urban-centric system, feel undervalued and invisible, and face multiple challenges.

National policy for NZ rural hospitals that adopts a rural-context-specific approach, is urgently needed. The current NZ health reforms offer a unique opportunity to enact this. Further research should be undertaken to understand the role of NZ rural hospitals in reducing health inequalities for rural and Māori communities.

Funding statement

This study was funded by a University of Otago Research Grant.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge NZ’s national rural health stakeholder organisations, which, at the time of writing, are joining to form a collective organisation, the Hauora Taiwhenua Rural Health Network, which will be well placed to strengthen and progress national rural health advocacy in NZ (https://rgpn.org.nz/rural-health-professionals-welcome-hauora-taiwhenua-rural-health-network/) .

We thank all the study participants for their assistance with this project.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/7583/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2008 - Obstetric services in small rural communities: what are the risks to care providers?