Introduction

The World Health Organization defines quality of care as ‘the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes’1. The Institute of Medicine’s six pillars of quality2 – care that is safe, effective, patient centred, timely, efficient and equitable – have been further developed internationally to include care that is accessible, affordable3, person centred1,4,5, integrated1, driven by information6, improves the work life of providers7, uses resources sustainably and is well led4.

The Triple Aim for healthcare quality was developed by the Institute of Healthcare Improvement and focuses on improving the individual patient experience of care, improving the health of defined populations, and reducing the per-capita healthcare costs for the population8. These principles were adapted to the Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) context9 to describe three key principles of improved quality, safety and experience of care for individuals; improved health and equity for all population groups; and best value for public health system resources10. Equity was explicitly included and value was defined as ‘benefit for patients for every dollar spent’9.

While the principles of healthcare quality are well articulated internationally, less has been written about applying these principles to rural contexts. Tensions exist in rural settings between community expectations and resources available to sustainably provide services to increasingly ageing populations, to attract and retain suitable workforces, and to provide patient access and overcome transport difficulties11-15. Increasing medical subspecialisation is leading to quality standards being developed with large urban hospitals in mind13,16,17, whereas many people from rural communities receive their health care in smaller rural hospital settings where subspecialty care may not be available. Requiring rural hospitals to adopt urban hospital quality standards risks centralisation of services with the loss of access to local services and increased demand on patients and their families to travel for health care18. Important safety aspects of rural health care, such as patient stabilisation and transfer to larger facilities, are not included in urban hospital standards17. Centralisation may occur without considering the wider economic and social benefits for rural communities of having services available locally or the potential broader impact of withdrawing services from rural communities13,16,19.

The Institute of Medicine’s Quality through collaboration: the future of rural health care considered their six elements of quality alongside the rural context of poorer health behaviours, isolation, workforce and financial barriers that impacted on access to core health services. Rural communities were encouraged to adopt population health awareness alongside a personal health focus when planning health services and resource allocation, with rural-specific quality improvement approaches and strong local leadership11.

No rural healthcare quality framework has been developed for NZ. Limited NZ research has explored the views of rural communities20 and healthcare providers21 about healthcare quality. The present research aimed to understand the principles of healthcare quality important to rural communities in NZ, through investigating the views of people providing and receiving this health care, particularly hospital-level care.

Methods

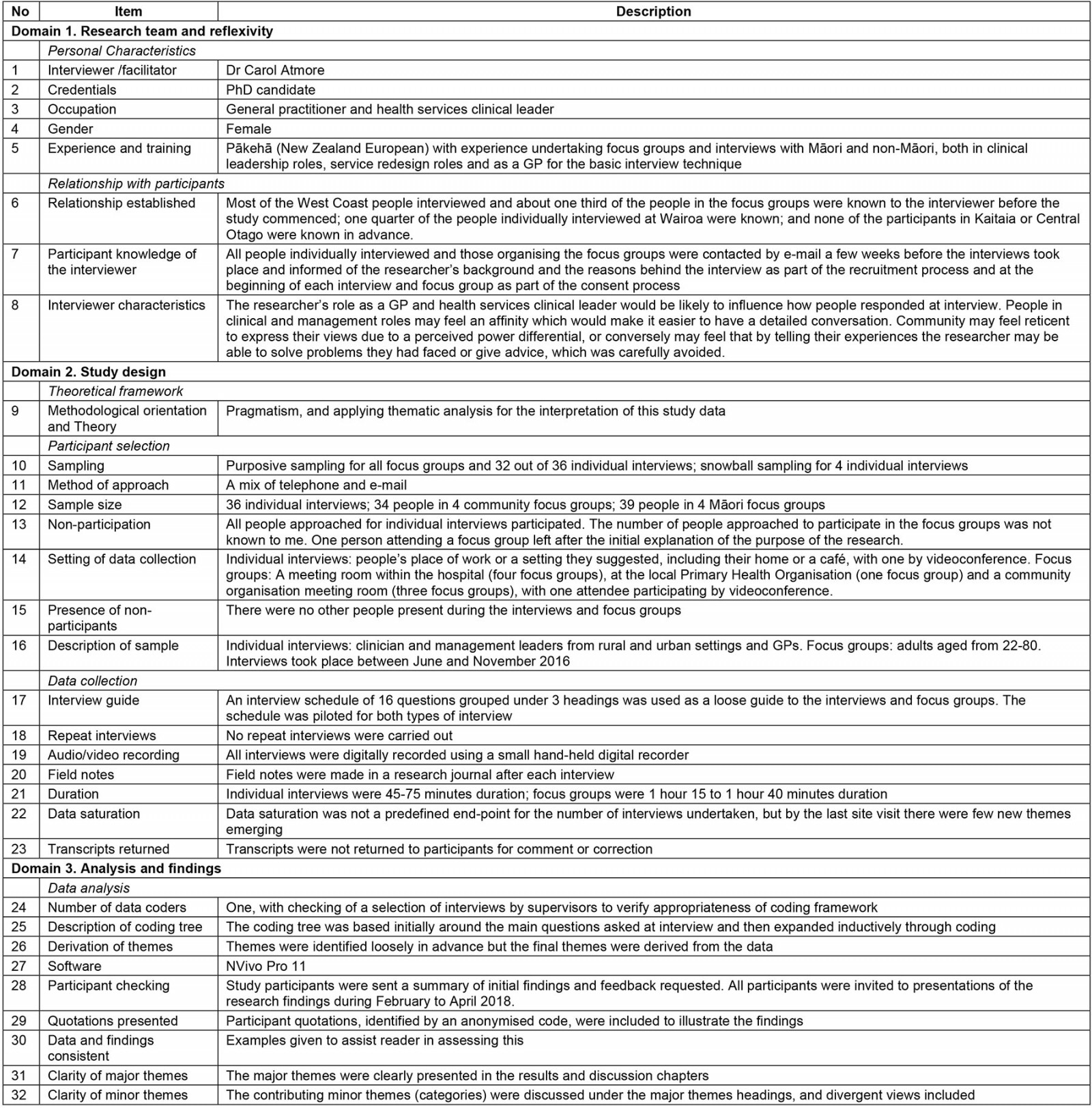

A pragmatic22 qualitative study was undertaken. Data were gathered using semi-structured interviews and focus groups, and interpreted using thematic analysis23. The methods used in this study are reported in line with the COREQ-32 framework24, and a checklist using this framework is available in Supplementary table 1.

Data collection

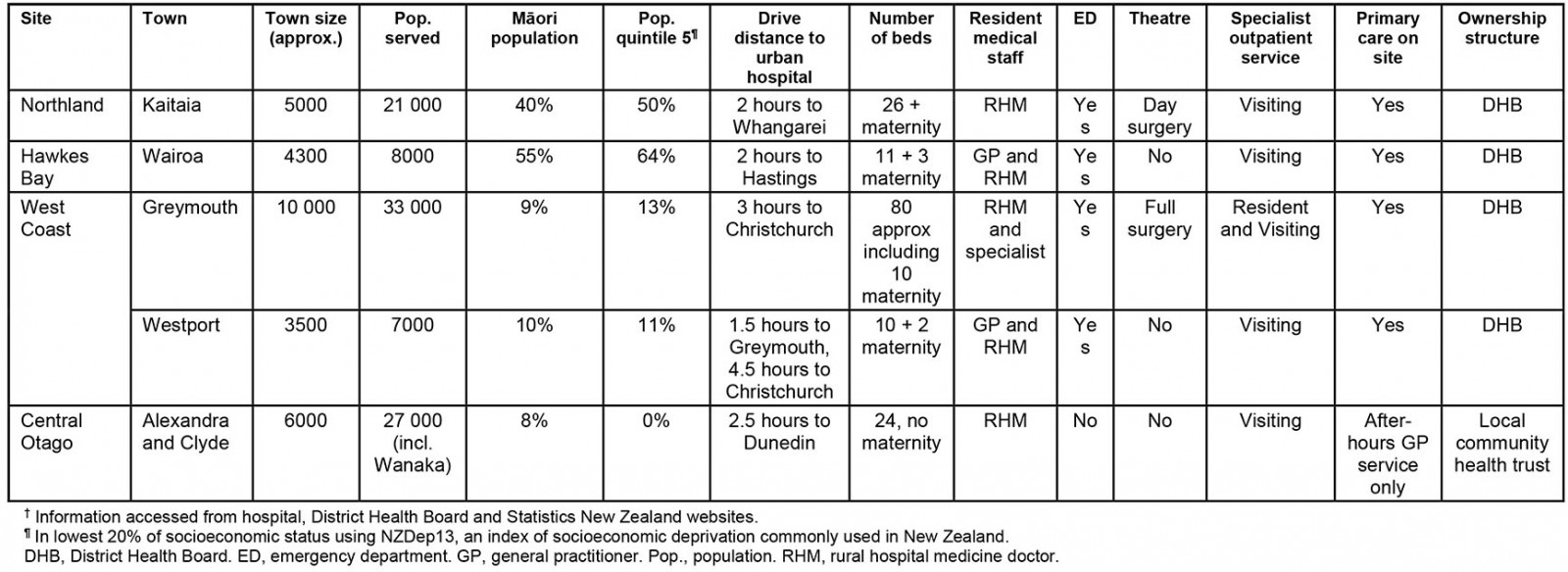

Four study sites were chosen through a purposive sample of all rural communities in NZ with access to rural hospitals25. ‘Rural’ was defined as small-town provincial NZ with populations of 10 000 or less and surrounding rural areas. Rural hospitals were defined using the Division of Rural Hospital Medicine classification26. The researchers aimed to study rural communities that contrasted geographically, by ethnic and socioeconomic population demographics, and by rural hospital size and ownership structures.

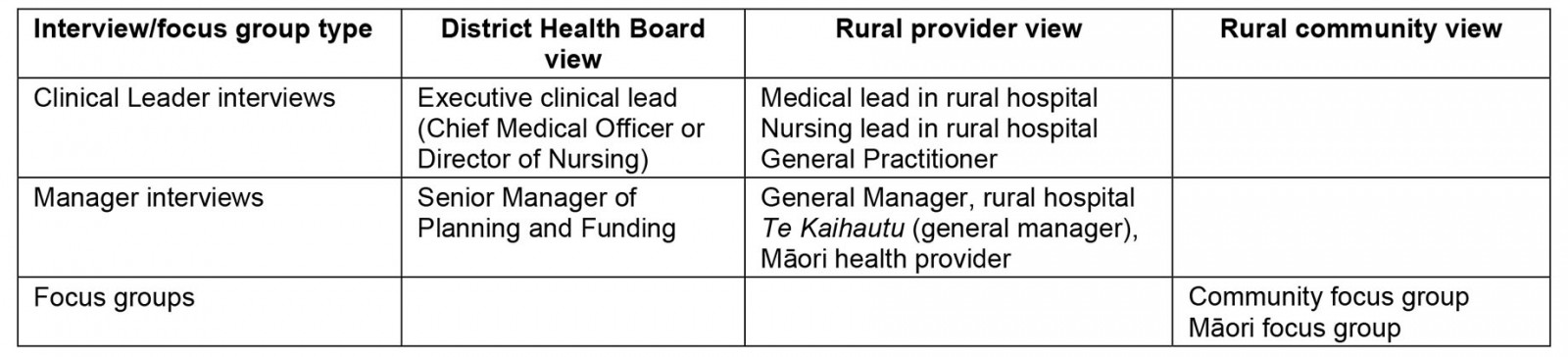

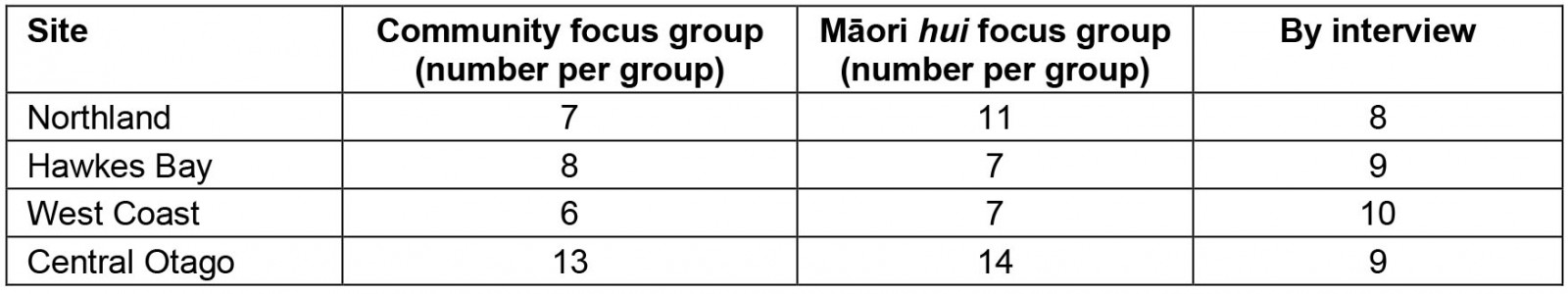

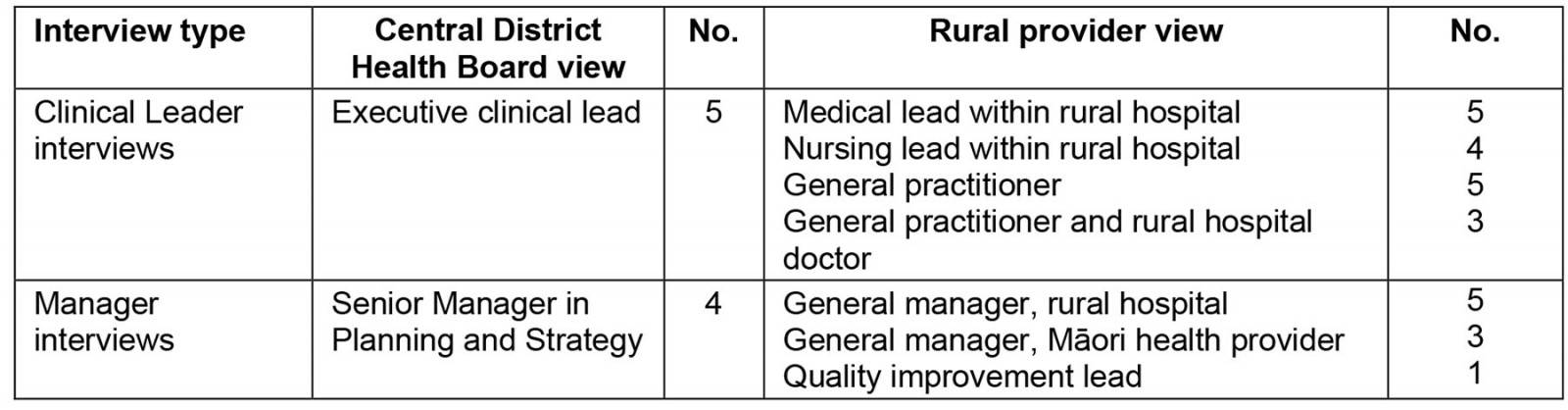

Service planners and clinical leaders of the District Health Boards within which rural communities were sited, clinical leaders in the rural health services and members of rural communities were purposively sampled25 as outlined in Table 1. Key contacts at each site assisted in identifying appropriate people to interview. Individual participants were invited by the lead author. Key contacts approached appropriate people in the local communities to participate in the community and Māori (the indigenous people of NZ) focus groups. Participants were approached by telephone and email.

The lead author undertook data collection between June and November 201627. Participants were interviewed in workplaces or other convenient settings, including homes and cafes, with one by videoconference. Four focus groups were held in meeting rooms within hospitals, one at the local primary healthcare organisation and three at community organisation meeting rooms, with one attendee participating by videoconference.

An interview schedule of 16 questions grouped under headings of rurality, quality and improvement enablers was piloted and applied. Regarding quality (the focus of this article), the topic guide for health providers focused on what quality meant in providing care to their rural communities and how it might differ from care provided to urban communities. In focus groups, the researchers explored different perspectives on the quality of hospital care received as rural dwellers. Although focused on hospital care, participants commented on the wider health system.

No repeat interviews were carried out. All interviews were digitally recorded and field notes were made after each interview. Individual interviews were 45–75 minutes in duration; focus groups were 75 minutes to 100 minutes in duration. Interviews with a range of stakeholders across four sites allowed data saturation where no new ideas were presented28 and by the last site visit few new ideas were noted. Transcripts were not returned to participants for checking.

The interviewer was a NZ European general practitioner (GP) with experience undertaking focus groups and interviews through previous clinical leadership and service redesign roles held, but not in Kaupapa Māori research approaches, in which research is led by Māori researchers and based on Māori principles and ways of working. All participants in the study were contacted by email prior to interview to explain the researcher’s background and the research rationale, and this was reiterated at interview as part of the consent process. At one site (the West Coast) most of the health providers interviewed, and about a third of the people in the focus groups, were known to the interviewer before the study commenced. A quarter of the people individually interviewed at a second site (Hawkes Bay) were known, and none of the participants at the other two sites were known in advance. The researcher’s role as a GP and health services clinical leader may have influenced people’s responses at interview, potentially positively for participants in clinical and management roles and potentially negatively for community participants who may have felt reticent to express their views due to perceived power differentials.

Table 1: Outline of purposive sampling frame for interview and focus group selection

Data analysis

To make sense of the data, an abductive22 thematic analysis23 approach was used. The interview question headings (derived from prior literature review) informed the initial coding framework. The framework was expanded and refined to accommodate new concepts. Co-authors reviewed a selection of interviews to verify appropriateness of the developing coding framework. The themes were developed through all authors reflecting on the deductive initial framework and inductive concepts developing in the data22. Data analysis was assisted by using NVivo Pro v11 (QSR International; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home).

Study participants were sent summaries of initial findings and their feedback was requested. All participants were invited to presentations of research findings during early 2018.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Human Ethics Committee, University of Otago, Aotearoa New Zealand (reference 16/084).

Results

The demographic details of the four study sites are shown in Table 2. Two study sites (Northland, Hawkes Bay) had large Māori populations, and high levels of socioeconomic deprivation, whereas the other two sites (West Coast and Central Otago/Lakes) had much lower Māori populations and lower levels of socioeconomic deprivation, but further travel distances to urban facilities. Rural hospitals ranged from 12 to 80 beds and were both government and community trust owned.

In total, 109 people participated in 36 individual interviews (which included one community member individual interview), four community focus groups (34 people) and four Māori focus groups (39 people), as shown in Table 3. All people approached for individual interviews participated. The number of people invited by the key contacts to participate in focus groups was unknown to the research team. One focus group attendee left after the meeting’s purpose was explained. Clinician and management leaders from rural and urban settings and GPs were interviewed individually, as shown in Table 4. Participants in focus groups were adults aged 22–80 years.

Two themes with subthemes regarding the principles of quality from a rural perspective and the differences compared with urban settings were developed and are presented here. Participant quotations are included to illustrate findings, using codes to identify roles, with sites allocated numerical codes.

Table 2: Comparison of sociodemographic data and hospital information by the four study sites†

Table 3: Research participants by number and site

Table 4: Description of health provider participants interviewed across all sites

Theme 1: Principles of healthcare quality for rural communities

There was general agreement among community and health provider participants about nine principles contributing to healthcare quality for rural communities. While focused on hospital settings, these principles related to the quality of health care for individuals and their families, for the rural community and the wider health system.

Patient and family-centred care in location of choice: Patient and family-centred care required patients and their families to be partners in decision making:

So, good quality, efficient and effective health care is really important, but I think that goes hand in hand with patient and whānau-centred [focused on immediate and extended family] care; patients and whānau having a say and being involved in how that care is delivered. (Planning and Strategy 2)

For people living in rural settings, this included taking their social and cultural contexts into account. Different people would have different priorities and might make different decisions about where they wanted to receive care as a consequence. People’s trade-off point for wanting to be cared for locally rather than being transferred to an urban hospital would differ. Clinicians and health services needed to enable these preferences to be enacted. The provision of patient- and family-centred care meant that families should be supported to be with their loved ones while they are in hospital, whether locally or at distant locations.

As close to home as can be done well: Participants indicated that care should be provided in the most appropriate setting to be provided safely, as close to home as possible. This acknowledged that what was achievable in different settings would differ. If care could not be provided in particular settings safely, people should be transferred to where it could be, for example an urban (‘base’) hospital:

Well, I guess I always think if I’m treating a patient, about the decision about whether you transfer them or not. I think to myself: am I giving the same standard of care that they would get in the base hospital? If I’m not, they should be in the base hospital. (Rural hospital doctor 3)

Quality is everybody’s job: Health care needed to be informed by best practice evidence, and rural providers needed to be competent across the broad skill set required. Focusing on quality was the job of all health providers, not just the dedicated quality improvement team:

Everybody is responsible [for quality improvement activities], because otherwise quality is somebody else’s job. (Rural hospital nurse 3)

This was particularly relevant in small hospitals, as the staffing levels meant that few specific quality-related roles existed and these were often part-time.

Consistent care across settings: Common things should be done well and unwarranted variation in care across different provider settings should be reduced. The same standard of care should be aimed for, and this should be monitored and audited. ‘Kia ora [hi] auntie’ (Community group 1) – the easy familiarity that working in small places brings – should not be an excuse for substandard care.

Team-based care across distance: Participants indicated that team-based care working over distance should be the norm. Healthcare teams in different facilities should have clear communication channels and processes so the patient journey through the system was smooth and there were no delays, breaks in service or barriers to access:

In the whole of New Zealand, no matter where you are, if you can’t get that care here directly then you should be confident that whoever is providing that care directly is linking you into another centre that is going to provide that different type of care. (Māori focus group participant 4)

Equitable health care particularly for Māori, and then for the whole rural community: When services were planned and provided, participants thought that the health of the whole region, and the rural communities within that region, particularly rural Māori, should be taken into account. This included identifying equity issues of access and outcomes, and the tensions therein, and addressing them:

Lastly, through all that we achieve equity – not equity of input, but equity of outcome. That would be the whole framing of quality. (Executive Clinical Lead 3)

This should underpin resource allocation decisions. Distance, transport and cost for rural people, particularly for rural Māori, were important equity challenges. Focus was needed on supporting people with limited financial means to access services, particularly when they and their families needed to travel to distant services. The wider determinants of health such as housing, education and employment within rural communities also needed to be considered.

Sustainable service models: Participants described how service planning needed to consider longer-term sustainability of local rural services and the workforce required to provide those services. This counterbalanced ‘closer to home’ as some services were acknowledged as needing certain patient volumes or economies of scale to provide high quality services sustainably.

Health networks to improve patient flow: Participants indicated that health care should be efficient and cost-effective. Improving patient flow between service providers and settings reduced waste within the health system. Well-functioning local networks between smaller and larger hospitals were noted as avoiding duplication and wasted effort by rural health services.

Value is more than value for money: While accepting that money was the unit of measure in the health system, many participants felt that value was a broader concept than just value for money. This was most clearly articulated by people presenting a Māori world view, for whom the concept of 'value for money' was seen as a Western medicine construct. If value was the focus, the money would follow as the service provided would be better quality:

I know the money is there, but if you get both right, you’ll get it right, and at the end of the day it will be a lesser cost. It’ll be a lesser cost monetarily, and it will be an added value to the person, because they received the right care – respectful care – the right care at the right time at the right place, which means that their hospital stay should be a little bit less. (Māori provider 4)

Value for care, valuing the person and their families’ experience of care, and providing timely respectful care, were described.

Theme 2: Quality across rural and urban settings – the same but different

Nature of care different: It was generally agreed that the nature of care provided in smaller rural hospitals was different from that of larger urban hospitals. Staff working at rural hospitals were seen to have more time to provide patient centred care, with a more family feeling:

They know some of the nurses. They’ve got their own GP looking after them in hospital. The family can visit and help out a lot more. From the patient’s mental health perspective, there’s a huge difference between being a number in a big secondary or tertiary hospital, and being back closer in a rural hospital. (General practitioner/Rural hospital doctor 1)

In contrast, staff in urban hospitals were seen as overworked and struggling to have time to care, as they were so busy with clinical tasks. Participants expressed concern that their family were not getting the best care in urban hospitals, so were reluctant to leave them alone, but had to because visiting hours policies were stricter.

Participants who were rural health providers thought that providing whole-person care through a generalist approach was better quality care. Most community participants agreed, but a few thought that the care received was better in larger centres, and noted that the familiarity of a smaller hospital sometimes risked masking poorer care:

So the care up here [rural hospital] was quite minimal … The care in [urban hospital] was definitely clearly better than here. When we got to [large city hospital] it was really clear that the care down there just superseded everything we had come across … and it probably saved her life. (Community focus group participant 2)

Patient transfers between hospital settings were frequently raised as high risk activities requiring diligent focus:

One of the main safety concerns I always have is about patient transfers. I think that’s one of the most unsafe things we do … In theory they should not really be, when they’re being transferred – they should not be in a lesser standard of care to what they’ve come from, but that pretty much always happens, so you’ve just got to judge how much lesser is okay and how much isn’t. (Rural hospital doctor 4)

When patients were discharged from an urban hospital, communication between different hospital sites and general practice was important. This allowed appropriate transport to be in place and prepared rural general practice teams to expect the person back into their community, allowing appropriate follow-up.

Patient experience as the measure of quality: A variety of opinions were expressed regarding conceptualising and measuring healthcare quality experienced in rural and urban settings. Participants were generally of the view that quality should be viewed from the patient experience perspective, and should be measured the same regardless of setting:

If you’re looking at it from a patient’s perspective, it should be measured the same. If the patient is at the end of it, we should be delivering the same standard of service irrespective of where we’re delivering it. (Planning and Strategy 4)

In contrast, a few participants thought that quality should be measured differently because of the underlying difference in services being provided at larger and smaller hospitals:

I guess they’re trying to achieve different things, aren’t they? So maybe they would need to be measured differently. (Rural hospital doctor 3)

Universal aspects of good quality patient care such as hand hygiene, fall prevention and procedural interventions were noted:

It’s only one quality for [fixing] a Colles’ fracture; it’s either done or it’s not – one quality. (General practitioner 4)

In addition to universal quality measures, rurally focused quality measures were suggested to reflect the differences in how services were provided in the rural context. These included measures of access to services and timeliness of treatment, such as transfer to and discharge process from urban hospitals, and measures of equity and fair distribution of resources.

Contextualising quality to local circumstances: Many participants noted that while consistent standards of quality from the patient perspective should be provided, this would be achieved differently in different settings. Consistent quality measures should be used across settings, and these should be contextualised to local circumstances when interpreting variance. Variance did not automatically mean ‘this one’s good and this one’s bad’ (Executive Clinical Lead 3). Further analysis was required to understand the causes of variance, whether it was acceptable or not, and any remedies required.

There was some frustration at assumptions from urban colleagues that generalist services provided in smaller hospitals were unfairly considered to be inferior. It was also noted that it was incumbent on generalists to maintain their skill set so this was not the case.

Taking patient complexity into account was important when interpreting quality measures. Rural patients transferred to an urban hospital were likely to be sicker than patients staying in rural hospitals, which needed to be considered when analysing rural patients’ outcomes across different settings. The case mix of patients being treated in different-sized hospitals also needed to be understood when interpreting quality measures, for example comparing tertiary hospitals providing national services to rural hospitals.

Discussion

This research used a qualitative methodology to explore healthcare quality, focused on hospital care experienced by rural communities. Rurally focused quality principles developed in this research included patient- and family-centred care including location of care preferences, as close to home as can be done well, with quality everybody’s job; consistent team-based care across distance equitable for Māori and then for the whole rural community and sustainable health service networks focused on value, where value was more than value for money, and included value for care and improving patient flow across distance. While the nature of care was different in different settings, patient experience should be the underlying measure of quality, and quality measures needed to be interpreted in the context of local circumstances, with rural-specific quality measures where appropriate.

Comparison with existing literature

Most of the quality principles and frameworks internationally2,4-6,8,10,29 do not address how quality can be conceptualised across communities of different sizes, different locations and different levels of resource seen in rural communities. Many of the principles described here are consistent with the limited literature regarding how quality principles are expressed in and modified by rural contexts11,15. In addition, the researchers identified the need to expand patient-centred care to include consideration of the impacts of decisions on families. This included decisions about where care was received (as previously identified in NZ research21). Also identified was a focus on value being more than value for money – not described elsewhere. A strong focus on equity for indigenous Māori in NZ was described.

The present study’s research supports the view that balance between centralisation and local access that is acceptable to local communities is required16,19,30. There are tensions in satisfying the different aspects of quality expressed in the Triple Aim. Experience of care may be the main focus for providers but each community of interest may think their needs are paramount for equity, and managers and planners may be left to decide how to achieve value for money through fair distribution. If hospital services are not available locally and patients need to travel, the quality and safety of the care they receive can compromise their experience of care, as their family may not be easily able to support them19,31. The risk of a homogenous view of healthcare quality is the tendency toward centralisation of hospital services into urban settings, to meet the safety aspect of quality, although evidence to support better quality through centralisation is lacking 19. When local services are lost from rural communities, rural people become less able to easily access services than their urban neighbours32. The value created by locally accessible rural services depends on the perspective taken. From a societal perspective, considering the full health system costs, such as patient and family travel, and the social costs of travel and family and work dislocation, rural hospitals could be considered of high value30,33.

The present study’s findings support the concern that has been expressed in the USA and other countries over applying national quality standards, designed largely in urban settings with underlying assumptions of available workforce and community resources, to rural settings13,14,17,18,31,32. The technical quality of hospital services is often assumed to be better when provided by larger urban hospitals, but research indicates no appreciable difference in patient safety34 and adverse events35 in similarly sized rural and urban American hospitals, or for people residing in rural or urban NZ settings36.

Patients needing transfer to other hospitals are the exception, and have associated adverse outcomes36-39. The present study’s findings support previous American research that highlights the need to develop quality standards around patient stabilisation and transfer and the communication required between rural and urban hospitals at these times17.

Strengths and limitations

The purposive selection of interviewees and focus groups conducted over four NZ sites with different sociodemographic compositions and access to different sized rural hospitals allowed a wide range of views to be gathered. The most obvious difference across the four sites was the levels of socioeconomic deprivation, with very low levels of deprivation in Central Otago/Lakes. The experiences Māori participants described in each setting were similar, irrespective of the proportion of local Māori to total population. The interviewer paid particular attention to reflexivity, regarding the influence of her own views and values on participant interactions and data analysis. She had a moderate degree of insider status40. Efforts to account for this included being open-minded about views expressed by participants, especially alternative concepts and counterarguments that challenged existing views, and keeping a reflective diary.

No members of the research team were Māori and this limits the researchers’ confidence that these findings have respectfully captured, represented and analysed the views of Māori expressed in the data. As the sampling frame included rural communities with access to rural hospitals, the findings are less applicable to communities without rural hospitals.

Implications for research and practice

The researchers hope that these findings regarding rurally focused quality principles will assist health policymakers, planners, providers and rural communities in the ongoing process of improving the quality of health services for rural communities. Community and health leaders need to embrace all three arms of the Triple Aim and have robust discussions about where the trade-offs lie, regarding what people are prepared to forgo (eg some services in some places) to obtain other benefits41 (eg greater equity of access to care). We hope the principles identified here as important to achieving quality health care for rural communities will assist in framing these difficult conversations. This is particularly relevant in light of the health reforms in NZ, where a key element is more equitable access to convenient and integrated health services42. Further research could test these principles with a wider range of rural stakeholders. In addition, future research could explore the views of urban working clinicians and communities on these issues.

While these research findings are particularly relevant to NZ, many of the findings will be applicable in countries with similar underlying health systems when locally contextualised.

Conclusion

Important principles of healthcare quality specific to rural communities have been identified, focused on the individual, population and system elements of healthcare quality. Patient and family preferences for where care was received, a broader focus on value beyond value for money and a strong focus on equity for indigenous people add to the existing rural principles described elsewhere. While the nature of health care provided in rural and urban settings is different, patient experience should be the underlying focus of quality, and the present study’s findings support the concept that quality measures should be interpreted in the context of local circumstances, with the development of rural-specific measures.

Funding

This study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand, Foxley Fellowship grant HRC16/056, and by the Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, through a Clinical Research Scholarship. The funding bodies had no involvement in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants, without whom this research could not have proceeded, and the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the University of Otago for funding this research.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/7635/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2020 - A mandatory bonding service program and its effects on the perspectives of young doctors in Nepal