Introduction

There is an obvious undersupply of general surgeons in rural Australia1. The issues of surgeon supply, recruitment and attrition are at the forefront of rural general surgery2. In recent decades, rural surgical provision has become a political issue with an increased emphasis on policy and funding to improve rural surgical access. Current initiatives have largely been directed towards evidence-based selection of medical students, junior doctors and surgical trainees with rural backgrounds and rural immersion placements during Australian medical school and surgical education and training (SET)1,3,4. Even though the formal education and training of general surgeons concludes upon the awarding of FRACS (Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons), most general surgeons undertake 1–3 years of further subspecialty post-fellowship education and training, commonly called ‘fellowship’ positions5. Currently these ‘fellowship’ positions are predominantly provided by metropolitan institutions, leaving rurally inclined general surgery Fellows with few options outside of large cities5. Dedicated rural fellowships (minimum 12 months) have the potential to better link Fellows with the local community and perhaps better prepare them for a consultant job at the same institution1. However, one of the barriers to providing rural surgical fellowships is that these positions need to be entirely funded by the institution itself, and fall outside the scope of Australian Department of Health Specialist Training Program and Integrated Rural Training Pipeline funding, which can contribute to the cost of developing and sustaining an accredited rural training position6.

Recruitment of specialist doctors rurally varies from other professionals due to the extensive length of postgraduate training required – often 5–15 years. The hurdles and opportunities encountered during this time have a major influence on where qualified specialist doctors choose to work7,8. Australian surgical (SET) trainees are generally older than those of other medical specialties, with a median trainee age of 32 years because surgical training is generally more competitive than other specialities. Many trainees must undergo multiple years of training not recognised by the RACS (known as ‘unaccredited’ training) prior to successful entry into a formal RACS SET training program. Consequently, surgical training occurs alongside major life milestones (eg marriage/partnership, childbirth and parenting) and trainees are more likely to have established roots at the end of their formal training – often in metropolitan regions where the majority of training takes place9,10. At present, there is no formal rural ‘end-to-end’ SET training pathway, with only one of the 27 surgical training hubs based rurally (Townsville, Queensland). In contrast, other specialties, including general practice (encompassing rural generalist), obstetrics and gynaecology, ophthalmology and emergency medicine, have established ‘end-to-end’ rural training schemes. These trainee doctors can undertake a large proportion of their training rurally alongside major adult milestones, often in the same location to create a sense of place and belonging1,11. Other challenges for rural surgical recruitment include the absence of specialised surgical equipment and ancillary services in certain locations, greater working hours per week, significantly higher on-call ratios, reduced access to continuing medical education/professional development and more unpredictable work hours when compared to metropolitan centres12,13.

Access to surgery in rural and remote regions is also a global issue. The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Initiative for emergency and essential surgical care identified that the recruitment and retention of health workers in remote and rural areas extends beyond just education (ie when the surgeon completes their training)14. It also includes regulatory interventions, financial incentives, and personal and professional support15. International literature has also highlighted the challenges to recruiting rural surgeons. Nations including the US, Canada, China and Scotland continue to struggle with rural surgical recruitment due to an ageing rural surgical workforce, lifestyle issues, inadequate remuneration and decreased interest in surgery among rural graduates. Key areas for international improvement include establishing broad-based training, increasing links to referral centres and focusing on rural training opportunities during surgical residency16-20.

Despite funding limitations, Bendigo Health established a rural general surgery fellowship in 2011 under the General Surgeons Australia curriculum21,22. Bendigo is a rural town in central Victoria, located 152 km north-west of Melbourne. It is classified as a Modified Monash Model (MMM) level 2 region (MMM levels 2–7 are defined as rural cities and towns) with a population of approximately 100 000 people1,23. Bendigo Health is a 734-bed health service providing elective and emergency surgical services to a catchment of 321 000 people across northern Victoria and southern New South Wales21. It is currently staffed by 10 general surgeons who also provide surgical outreach to surrounding rural towns. This study aimed to review Bendigo Health’s general surgical fellowship program to determine first if rural general surgery fellowships can assist in providing a rural general surgery workforce, and second how this is achieved in an Australian context.

Methods

Each year from 2011 to 2021, one general surgeon completed the Bendigo Health fellowship, totalling 11 surgeons. The fellowship is a 12-month program commencing in February of each year (in conjunction with the medical recruitment cycle). All 11 ex-Fellows were invited to complete the interview. Participants were invited by email with an information sheet and consent form, with one reminder email issued. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in March 2022 with nine general surgeons who completed fellowship training at Bendigo Health between 2011 and 2021. Two general surgeons did not respond to the invitation to participate. The interview explored demographics, background, family, rural training exposure, subspeciality interests and the topics of returning, remaining in and leaving Bendigo.

Interviews were conducted by the principal investigator (JP). Two participants were interviewed by telephone and the remaining seven were conducted in person. All interviews were audio-recorded. JP was a junior doctor (house medical officer/resident) when the interviews were conducted. All participants were fully qualified surgeons at the time of the interview. Researcher reflexivity was maintained throughout the interview and data collection process by the maintenance of field notes and a reflexive diary by author JP following each interview to mitigate personal biases and subjectivity. Each transcript of interview was returned to the individual participant for member checking and feedback.

Interviews were recorded, transcribed, deidentified and analysed using NVivo v12.0 (QSR International, https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo) – a qualitative data analysis software allowing organisation, analysis and insight generation from unstructured qualitative information. Transcripts were coded independently by two researchers (JP and JB). The same two authors recursively developed and refined a thematic structure. Thematic analysis established on grounded theory was incorporated into the coding and theming of data. This was achieved through the collected coded transcripts and field notes, which were transformed into new themes. Concepts and notes developed during the interview process were repeatedly revisited, discussed, refined and categorised into themes. The researchers discussed and arranged the findings until consensus was achieved about the validity and suitability of four themes. The methods used in this study were reported according to the COREQ-32 framework, as presented in the checklist in Appendix I24. Four key themes were subsequently identified. Detailed quotes supporting each theme are shown in Appendix II.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Bendigo Health Human Ethics Committee (LNR/85700/BH-2022-309854).

Results

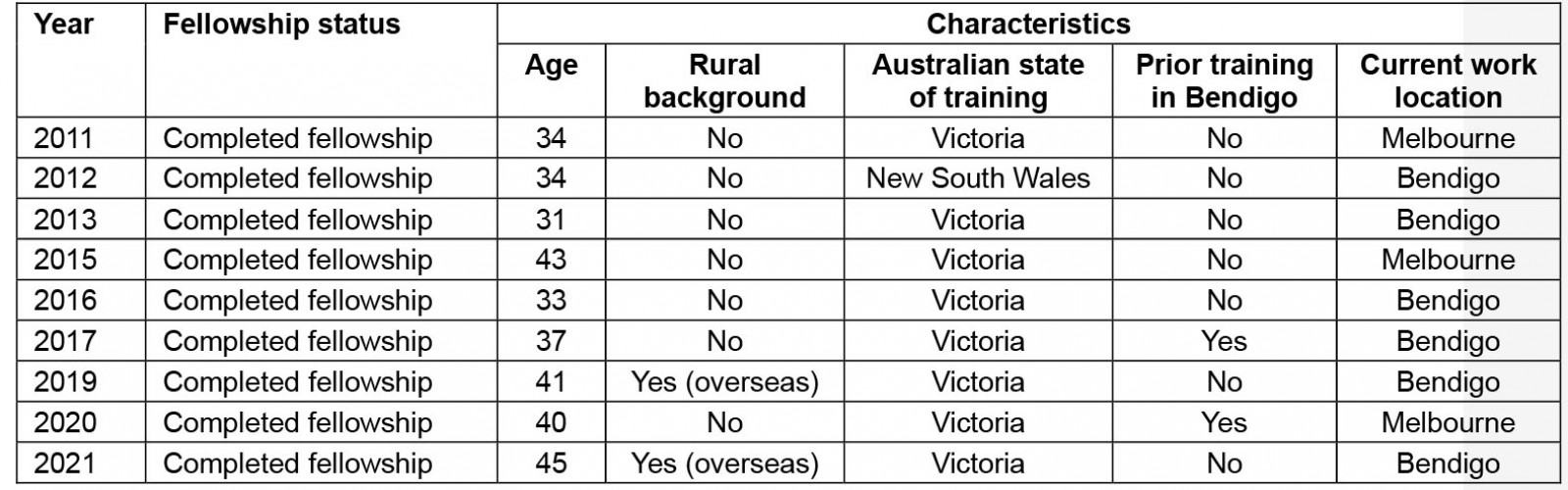

Nine former Bendigo Health general surgery Fellows were interviewed. There were four (44.4%) females and five males. Median age at time of fellowship was 37.6 years. Six (66.7%) remain in Bendigo working as general surgeons and three work in metropolitan centres. Only two (22.2%) Fellows had a rural childhood background. On average, Fellows undertook 22 months of formal SET training in a rural (MMM levels 2–7) location and only two (22.2%) had previously worked in Bendigo. A brief summary of each participant is presented in Table 1. Further reporting of demographics has been omitted to protect respondent anonymity. Four themes were identified from responses and are described below.

Table 1: Summary of Interview participants

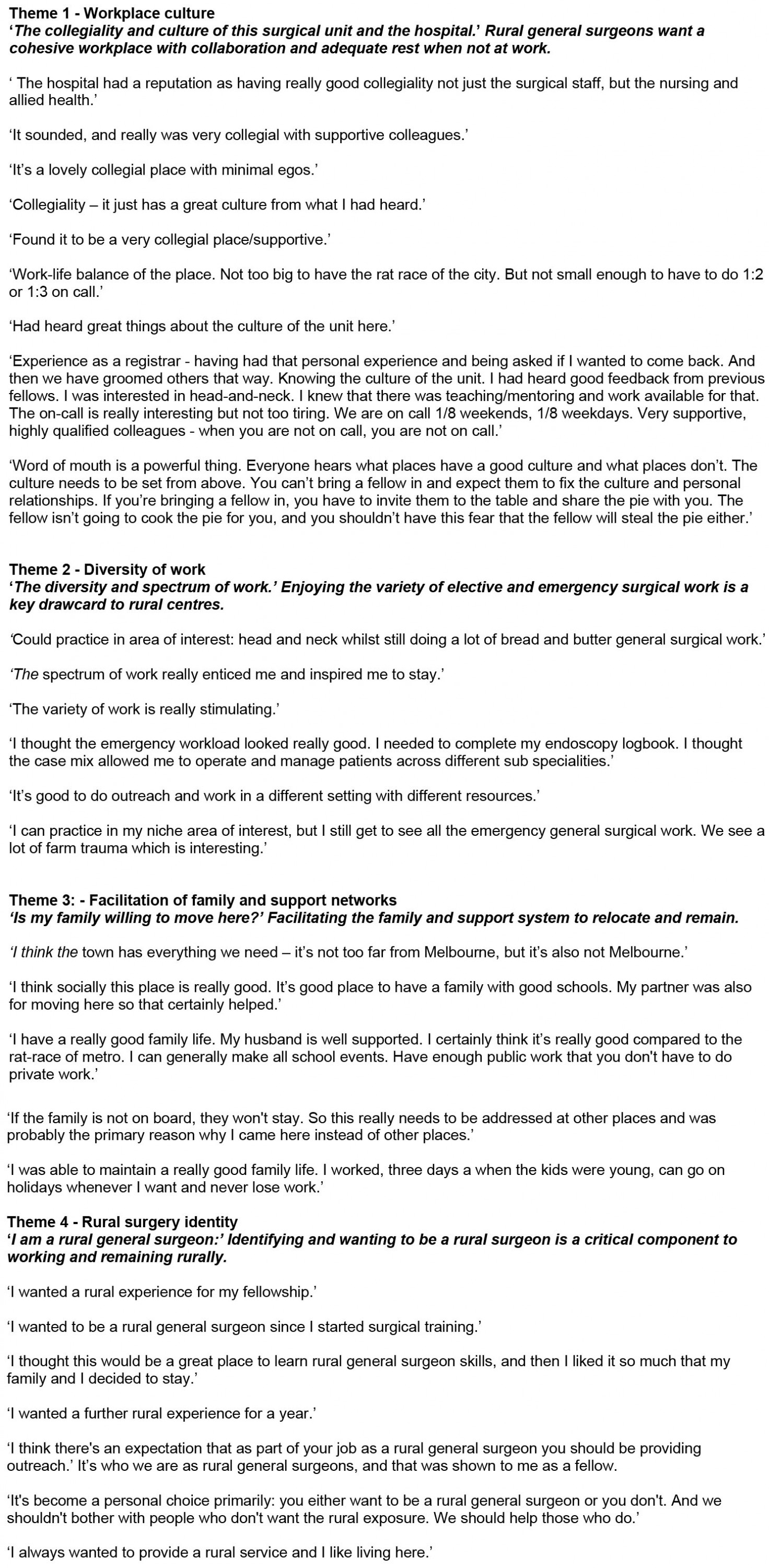

Theme 1 – Workplace culture

‘The collegiality and culture of this surgical unit and the hospital.’ Rural general surgeons want a cohesive workplace with collaboration and adequate rest when not at work.

This describes participants’ experience with workplace culture and cohesion. The collegiality and culture of a surgical unit can affect an institution’s overall reputation. Fellows will have rotated through multiple surgical units as registrars and worked within many multidisciplinary teams during SET training. They rely heavily on reputation and workplace culture when deciding where to work:

Word of mouth is a powerful thing. Everyone hears what places have a good culture and what places don’t. The culture needs to be set from above.

Fellows relied on personal experience as registrars or feedback from previous Fellows when deciding where to pursue a rural fellowship. Participants commonly expressed that their surgical department heads often identified current or potential Fellows as rotating registrars who appeared to be a ‘right fit’ that aligned with the institutional culture and subsequently prepared them to return as a Fellow and remain as a consultant.

In deciding to continue as a rural general surgeon post-fellowship, the desire for sustainable working hours, with a minimum of one-in-four on-call rotation was a driving factor. Respondents expressed a desire to not work arduous and unnecessary hours, and those who remained in Bendigo preferred to not work exclusively in a smaller, more remote centre, where a one-in-two or one-in-three on call was often expected. They expressed satisfaction of working in a one-in-eight on-call consultant service, with periodic rural outreach on-call postings. They also expressed that ‘when [they are] not on call, [they are] truly not on call’, as ‘[their] colleagues are very capable’ – emphasising the importance of mutual trust among surgeons.

Theme 2 – Diversity of work

‘The diversity and spectrum of work.’ Enjoying the variety of elective and emergency surgical work is a key drawcard to rural centres.

This identifies the appeal of a diverse elective and emergency surgical case mix. This theme explores that a variable case mix allows participants to practise in their areas of interest, as well as managing patients across different surgical specialities. The Bendigo Health general surgical unit is supported by on-site orthopaedic, plastics and urology for elective and emergency presentations. However, as there is no on-site vascular, cardiothoracic, otolaryngology or paediatric surgery, surgeons and Fellows are empowered to practise across surgical disciplines – a clear drawcard for prospective Fellows. Second, in the increasingly subspecialised world of general surgery, general surgeons in Bendigo can still practice across disciplines while also becoming local subspecialty leads, increasing opportunities for surgical leadership. Surgical diversity is further aided by facilitated opportunities for respondents to perform general surgery cases at smaller rural centres within the local catchment. This allows the rural general surgeon to regularly operate in different resource environments and diversifies their patient/case mix.

Working at a relatively large rural centre, respondents felt well supported by multidisciplinary services, including anaesthesia, intensive care, oncology and radiology, alongside subspecialty surgery. This enables the rural general surgeon to perform complex cases such as radical breast excision and reconstruction, ultra-low anterior resection, and extensive neck dissection. In smaller rural centres, which may not have adequate multidisciplinary support and advanced infrastructure/equipment, surgeons are more restricted in their scope of practice.

Theme 3 – Facilitation of family and support networks

‘Is my family willing to move here?’ Facilitating the family and support system to relocate and remain in a rural town.

Successful relocation of a young Fellow’s family was identified as a critical barrier to retaining their services over the long term. Bendigo Health does not have its own general surgical training network/hub. SET registrars rotate from metropolitan centres in Melbourne where they are primarily situated during training. However, SET training and fellowship typically occur alongside major life milestones such as marriage/partnership, pregnancy and starting a family, which can be negatively affected by relocation25. All respondents were located in metropolitan cities during their training, but relocated to Bendigo for fellowship. Four of the Fellows had children at the time of fellowship. Of those, two relocated their families (partner and children) to Bendigo, and two did not – choosing to commute regularly instead. The two Fellows who relocated their families continue to work in Bendigo as staff surgeons, and the two who did not only work in metropolitan centres. This is a powerful indicator and suggests that family dynamics play a key role in recruiting candidates for the long term. Efforts should be made by rural recruiters to explore the family dynamics of potential candidates and, where possible, facilitate opportunities for partners and/or children.

All Fellows who remained on as surgeons stated that they ‘enjoyed the city of Bendigo’, and that the community provided a great lifestyle for their family, with excellent schooling and work opportunities. Fellows expressed that if their family were not ‘on board’, they would not have stayed, and acknowledged the large role their family played in their surgical journey. Furthermore, respondents noted that Bendigo ‘caters to a wide array of educational and cultural interests’, which smaller towns would not be able to offer. Finally, they concluded that the town had ‘everything [they] needed’, ‘without the hassles of a metropolitan city’, although it was also ‘close enough to Melbourne’ if they needed to go.

Theme 4 – Rural surgery identity

‘I am a rural general surgeon.’ Identifying and wanting to be a rural surgeon is a critical component to working rurally.

This final theme explores Fellows’ sense of identity and its impact on their decision to work as rural general surgeons. While the traditional provision of rural general surgery has relied heavily on international medical graduates and return-of-service obligations, the desire to work rurally is an increasingly personal choice for Australian graduates. Participants who remained in Bendigo ‘wanted to be rural surgeon[s]’. They expressed that ‘it’s become a personal choice, one either wants to work rurally or not’. Respondents stated that rural general surgery fellowships should be prioritised for candidates with a strong track record and desire to work rurally, rather than ‘individuals who just want/need a job’. The Fellows who did not stay post-fellowship stated that they desired a rural experience but did not necessarily feel a strong inclination towards rural general surgery. It was evident that those who stayed in Bendigo post-fellowship strongly identified as rural general surgeons. Furthermore, Fellows who remained were passionate about the provision of a sustainable general surgical service to the greater community and felt a strong sense of responsibility towards the local people.

Discussion

This study has explored the Bendigo Health general surgery fellowship position to determine if fellowship positions can be used to sustain a rural general surgery consultant workforce. By interviewing previous Bendigo Health general surgical Fellows, this research finds how Bendigo Health has recruited and retained rural general surgeons post-fellowship. Two-thirds (66.7%) of Fellows stayed as rural general surgeons despite only 22.2% coming from a rural background and only 22% having worked in Bendigo previously (22.2%). A dedicated rural general surgical fellowship may be a new area for policy and funding efforts to address rural general surgery undersupply. We demonstrate that positive workplace culture, diverse case mix, family buy-in and recruiting candidates who identify with rural surgery can help to deliver a sustainable rural surgical workforce. The fellowship year enables the surgeon and their family to not only fully evaluate the career option of consultant practice, but also the realities of living in the region.

The culture of the surgical unit is critical in influencing where surgeons decide to work. For individual surgeons, institutional culture is largely dictated by local surgical leadership. Units where surgical leaders operate effectively within an environment of change, compared to those that enable and tolerate ‘long established traditions which have normalised unprofessional … behaviours’ are not perceived by new rural general surgeons as places where they would like to establish their careers26. The impacts of poor surgical culture and cohesion are likely to be further magnified in resource-poor rural hospitals where healthcare capacity is limited. Even though most Fellows came to Bendigo as a result of ‘word of mouth’ and feedback from colleagues, culture can only really be experienced first-hand in how you are individually treated, especially as many of the Fellows were female and ethnically diverse. Organisation culture is a cornerstone of determining whether a young surgeon can see that they could happily work in the institution27,28.

Workplace culture also encompasses a respect for work–life balance, which is a priority for young surgeons. Today’s general surgeons have different values and priorities, placing a greater emphasis on balance instead of surgery as ‘one’s life’s work’29. This is particularly pertinent in the rural workforce, where many rural general surgeons were historically forced to work alone (or in very small teams) in smaller towns leading to taxing on-call demands and limited personal time. The RACS presently advocates for a roster of no more than one-in-four on call to facilitate patient safety and physician wellbeing1. Our research further supports the importance of the on-call workload in recruiting and retaining rural general surgeons. Our Fellows deliberately chose to stay in Bendigo for the manageable on-call load, coupled with a collegial and collaborative surgical unit embracing the principles of diversity, equity and inclusion. Being able to recruit gender-diverse and ethnically diverse young consultant surgeons is also likely to have a positive impact on the community with improved patient outcomes30.

Rural general surgeons have historically operated with a diverse skillset across many surgical subspecialities. This research highlights that this remains an ongoing draw for contemporary rural general surgeons31,32. In Bendigo, general surgeons routinely perform vascular and paediatric surgical procedures (provided they have adequate training), particularly emergency cases. The case mix is further diversified by regular outreach to smaller rural centres, allowing surgeons to practise in different resource settings. Our findings show that the appeal of a variable case mix has been critical in attracting and retaining general surgery Fellows at Bendigo Health. Moreover, the presence of strong multidisciplinary services, particularly critical care and oncology, enables major cases (eg ultra-low anterior resections, breast reconstruction, major head and neck cases and oesophagectomy) and facilitates subspeciality interests33-37. This was identified as a strong incentive for the retention of the Bendigo general surgical Fellows because it provided the opportunity for a degree of subspecialisation while also maintaining diversity.

Our results also show that familial support is vital to the retention of young surgeons at a rural service. This has previously been shown by Ostini et al, who demonstrated that a poor support network is associated with poor work satisfaction, and lower physician retention in rural communities38. Furthermore, this phenomenon has also been documented in the Australian rural general practitioner workforce where children’s education and partner employment opportunities have a large impact on general practitioner recruitment and retention39. It is important that rural healthcare providers understand and enable the non-professional needs of early career surgeons when making recruitment decisions7,40. We acknowledge that supporting surgeon families may require complex infrastructure and societal change that is outside the jurisdiction of the healthcare system. However, political will to improve rural infrastructure may lead to better employment and educational opportunities, and this may be a key factor in bolstering the rural general surgical workforce.

Finally, this research demonstrates that retention of rural general surgeons is enhanced if the individual identifies as a rural general surgeon. Fellows who remained in Bendigo strongly identified with rural general surgery throughout their interviews, and that was a key feature of why they chose to stay post-fellowship. While rural general surgeons are typically male, older and overseas trained, the Fellows from our cohort were younger, gender balanced and Australian trained41. Despite the challenges that exist in rural surgery, this research further highlights that Bendigo surgeons ‘love being a rural general surgeon[s]’ and enjoy the associated challenges. This shows that identity is crucial in the retention of rural general surgeons and may explain why government-enforced programs aimed at fulfilling rural surgical shortages may struggle to create sustainable change unless the general surgeon identifies as a rural general surgeon.

For many Australian-trained surgeons, there are potential risks involved with moving to a rural setting where they have never worked before (as was the case for many of the Fellows). A 12-month fellowship opportunity gives the Fellow a chance to live in a region, knowing that they can easily move on without affecting their career prospects. This also enables the general surgeon’s family to have time to assess whether the Fellow’s partner’s planned long-term workplace would allow an appropriate family life. In addition, smaller general surgical units can be places of greater tension if there are personality clashes, and a year of training enables the existing general surgeons to get to know their junior colleagues and make sure they will fit in with the ‘norms’ of the local work environment.

The strength of this study is that all Fellows who stayed on as general surgeons expressed similar themes as to why they chose to stay – culture, work diversity, family support and their identity as rural general surgeons. This research provides a crucial snapshot into why recently graduated general surgeons choose to work rurally. The primary limitation of this study is that this is a thematic analysis of a single centre in a single town. We recognise that all rural centres are different and our results are not generalisable across all of rural Australia or internationally. However, given the return investment of our rural general surgery fellowship program in Bendigo (67% retention rate with only 22% rural background, and only 22% having worked at Bendigo previously) we believe that fellowship positions may be useful in developing a sustainable surgical workforce throughout rural Australia and should be considered for federal funding. This aligns with the WHO evidence-based recommendations to improve attraction, recruitment and retention of health workers in remote and rural areas that a year of experience in a setting extends beyond where the surgeon completes their training, but enables young surgery consultants to assess the financial incentives and personal and professional support prior to committing to establishing a practice in a rural location15. An important next step is to see whether other models of post-fellowship training in rural and regional centres has resulted in recruitment and establishment of a sustainable consultant workforce.

Other limitations include the small number of participants interviewed due to the small sample size. A larger sample may have resulted in a greater breadth of data, improving the generalisability of our findings. However, interviewing more participants may have compromised the depth of discussion and subsequent analysis. Furthermore, as three of the four authors of this study are current employees of Bendigo Health, participants may have been less willing to disclose the negative aspects of their fellowship experience at the institution. Finally, the unique population distribution and surgical service capabilities (including surgical training) within rural Australia may limit international replicability.

Conclusion

This research highlights critical concepts that should be used to improve and assist rural towns with recruiting and retaining general surgeons beyond current policy. The rural general surgery fellowship that enables first-hand experience of future workplace culture and family ‘buy-in’ alongside work diversity has provided an effective retention of general surgeons at Bendigo Health. Rural general surgical fellowships may offer an additional means to develop a sustainable rural general surgical workforce across Australia.

Funding

The authors were not in receipt of a research scholarship or grant.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

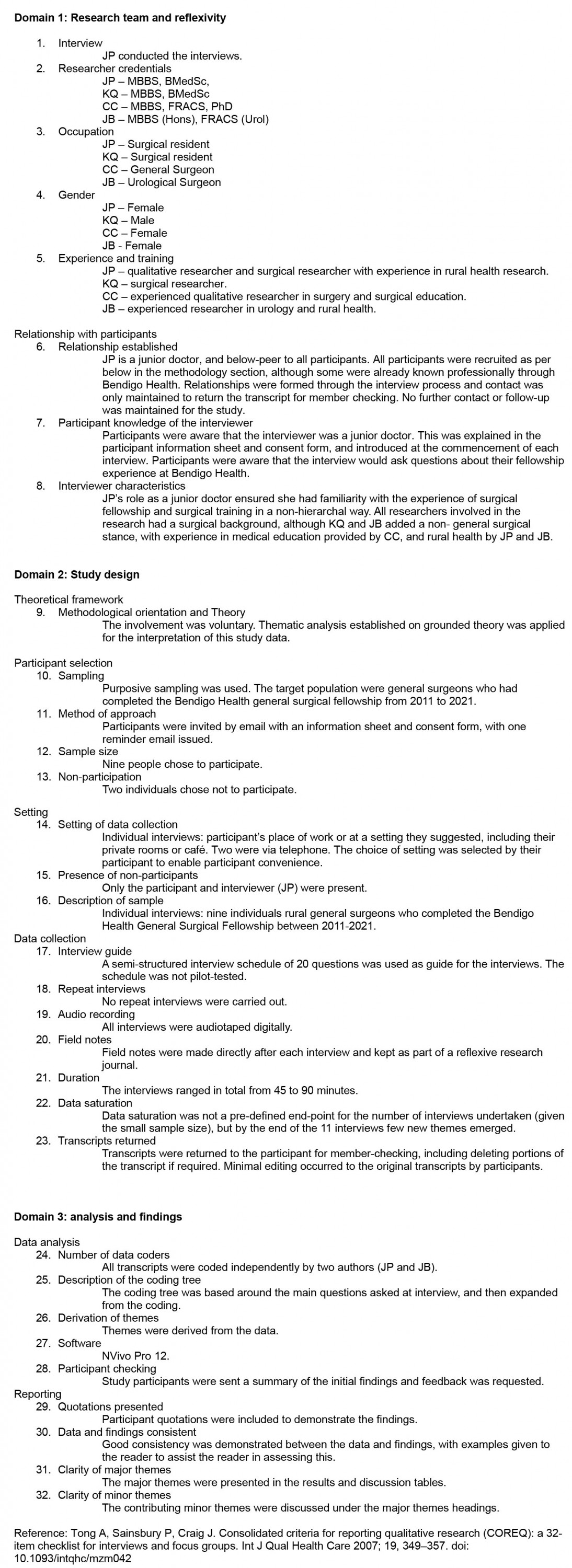

appendix I:

Appendix I: COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) - 32 checklist

You might also be interested in:

2020 - Does driving using a Green Beacon reduce emergency response times in a rural setting?

2018 - Prevalence of Exposure to Occupational Carcinogens among Farmers