Introduction

Australian health services collect patient experience data to monitor, evaluate and improve services and subsequently health outcomes, in response to organisational and national health services’ quality and safety assurance frameworks and processes. In the Northern Territory (NT) local standards and frameworks such as the NT Health Aboriginal Cultural Security Framework 2016–20261 articulate with the national Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards2. Both emphasise the importance of consumer participation in service improvement that reflects the cultural, linguistic and contextual diversity of service users. However, obtaining authentic patient experience information to inform improvements relies on the quality of data collection processes and their responsiveness to the cultural and linguistic needs of diverse populations. This is particularly crucial in a context such as the NT, where more than 100 First Nations languages and dialects are spoken3 and the majority of First Nations residents speak one or more of these languages at home4.

Survey tools are commonly used for collecting patient experience information in research and health service contexts. Previous studies have identified concerns about the quality of information collected when using survey tools with First Nations populations, constraining their opportunity to inform improvements healthcare5-7. A range of issues must be considered when using surveys in contexts where languages and cultures are different to those in which the surveys were developed. Existing tools are underpinned by Western biomedical models of health8 and adaptions mostly involve language translation9, neglecting the influence of culture and context10. Challenges in achieving equivalence of meaning when translating existing surveys into Australian First Nations languages include no equivalent or multiple equivalent words and different concepts associated with time and health beliefs6,11. The style of language, attributed meaning, clarity of the question and consistency of interpretations12 are just some aspects of translated surveys that must be assessed, requiring extensive time and resources5,13.

The quality of patient experience data is also influenced by other factors. The extent to which survey tools capture what is important to First Nations Australians, reflect the diversity of world views and take into account the ongoing impacts of colonisation must also be considered6,11,14,15. For First Nations Australians who primarily speak a language other than English, the opportunity to engage in their preferred language is a human right16 and crucial to ensure culturally safe and effective communication17. Congruence with cultural communication protocols also impacts the authenticity of information collected through survey methods for speakers of First Nations languages. A study by Mithen et al found a disconnection between reported satisfaction levels when multiple choice and free-text responses were compared18. Respondents who gave positive multiple-choice ratings conversely reported concerns relating to social-emotional support, loneliness, racism and food in their free-text responses18.

Cultural protocols that can influence authenticity of collected information include the acceptability of questions as well as what information can be shared, with whom, in what circumstances and in what way. Research conducted with Yolηu (First Nations Australians from North East Arnhem Land) found that for questioning to be acceptable the following pre-conditions were important: rapport-building for reciprocal patient–health–carer relationships, alignment with cultural decision-making models, shared understanding of healing concepts, use of first language, and opportunities to tell their deep story as a culturally acceptable way for sharing information19. These findings align with decolonising methods of data collection that prioritise First Nations voices such as the storytelling methods recommended by Howard et al8, the power of ‘talk’20 and Bessarab’s seminal work on ‘Yarning’21.

In contexts of cultural and linguistic diversity, best practice models emphasise both the time required for adapting surveys13 and the need for co-design through shared expertise in language, culture and context6,22,23. Engaging First Nations language speakers currently residing in specific geographical locations is also noted as important for ensuring both linguistic and cultural currency24. Brown et al23 used this approach to produce a culturally acceptable and valid Central Australian version of a depression screening instrument previously validated for use internationally. Increasingly, First Nations communities, health professionals and researchers are driving the development of survey tools that account for and are responsive to the culture, needs and context of First Nations Australians6,11,22,23.

Effective communication between health services and speakers of First Nations languages is imperative to address persistent disparities in health outcomes between First Nations and other Australians through health service improvement1,25. In the rich and diverse language environment of the NT, where more than 60% of First Nations residents speak a First Nations language at home4 there is a recognised need to improve the tools used to assess patient experiences of care18. This study explores the challenges and considerations in collecting authentic patient experience information through survey methods with speakers of First Nations languages. First Nations language experts were engaged in a critical review of two survey tools: a national hospital patient experience survey adapted for use with speakers of First Nations languages, and a survey under development for collecting patient experience information in a research project with First Nations Australians receiving renal care.

Methods

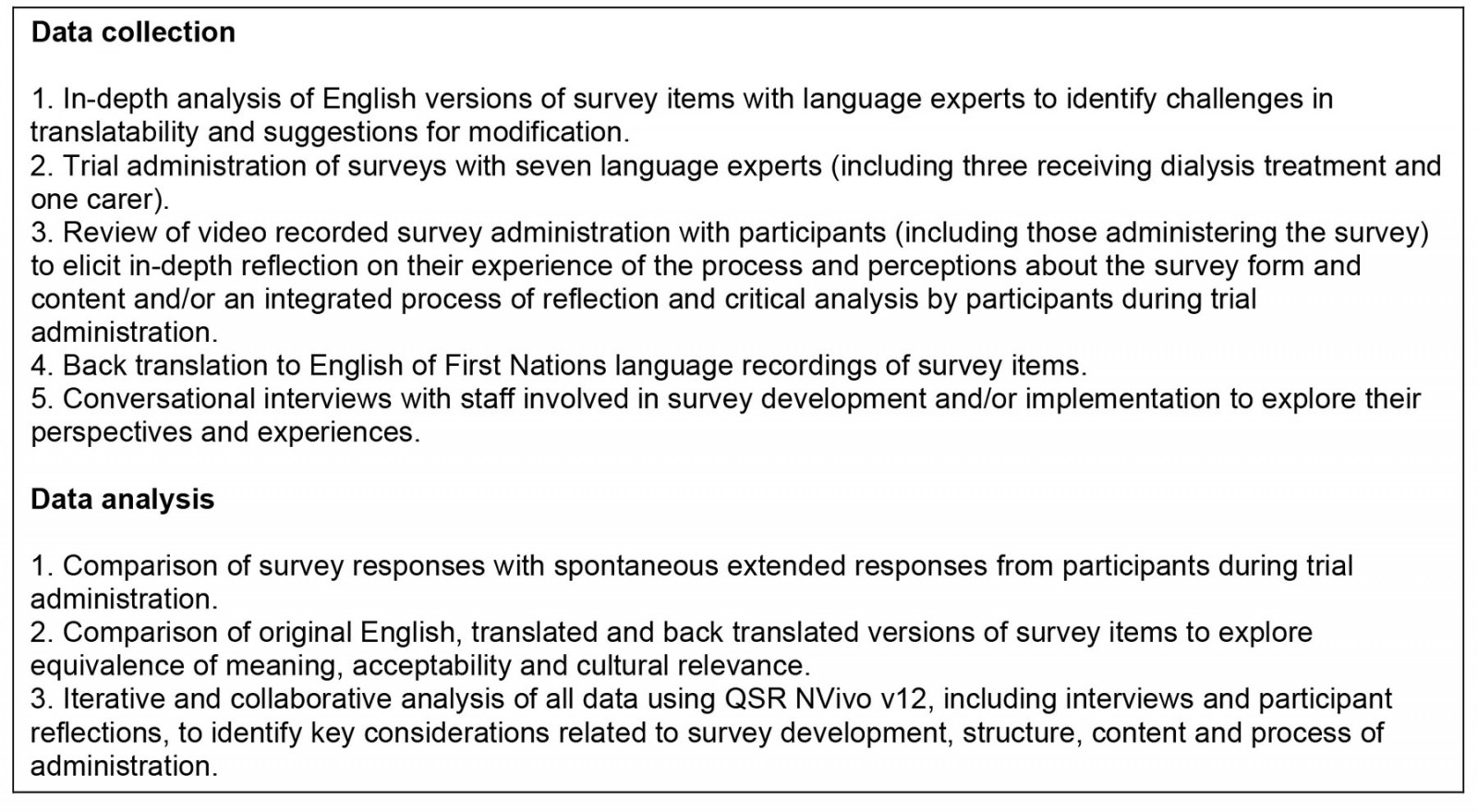

This collaborative qualitative study explored the acceptability, relevance and translatability of two patient experience survey tools intended for use with speakers of First Nations languages. First Nations language experts, health staff and researchers with expertise in intercultural communication and interpreters engaged in an iterative process of critical review using multiple qualitative methods (Box 1). The research approach was emergent and pragmatic26, incorporating methods that were flexible and responsive to each context and guided by First Nations language experts engaged in the study.

Participants

Nineteen First Nations language experts (4 male and 15 female) from five language groups (Djambarrpuyηu, Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara, Arrernte, Warlpiri) with relevant experience and interest in health communication and interpreting, as well as one non-Indigenous interpreter, participated in the study. Potential participants were identified through the networks of both First Nations and non-Indigenous members of the project team who have extensive prior experience in collaborative intercultural research. Participation was voluntary and written informed consent was obtained from all participants following explanation about the project in the participant’s preferred language. In collaboration with members of the research team with whom they had an existing and culturally appropriate relationship, language experts participated in one or more elements of the critical review process (Box 1) depending on their individual interest, expertise and experience. For example, language experts who were also registered interpreters engaged in initial review of acceptability, relevance and translatability of survey items, trial administration of surveys and/or back translation of First Nations language recordings of survey items. Seven First Nations language experts participated in trial administration of surveys (including three who were also receiving renal dialysis treatment and one who was a carer of a family member on dialysis). All language experts engaged in assessing both the process and content of survey tools and were paid for their time. Participants also included five health staff involved in the development and/or implementation of the adapted AHPEQS survey.

Box 1: Summary of study methods

Survey tools included in the study

Two survey tools intended to collect patient experience information from speakers of First Nations languages were reviewed in this study: the adapted Australian Hospital Patient Experience Question Set (AHPEQS) and the Return to Country (RtC) Project survey tool.

The AHPEQS was developed by the National Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care to assist health service organisations to achieve National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. The national AHPECS survey was modified by the NT Department of Health for use with First Nations language speakers in NT hospitals through an extensive adaption process to produce an iPad-based version incorporating oral recordings in First Nations languages. The development process included a plain English text version of the original AHPEQS and subsequent translation into six Aboriginal languages with the assistance of registered interpreters. The modified text and iPad Aboriginal language versions of the adapted AHPEQS were used in this study.

The RtC Project was developed as part of an National Health and Medical Research Council funded study (APP1158075) and combined several existing survey tools to create five domains: demographic and housing, wellness, experiences of racism, health literacy, and care and treatment. The purpose of the survey is to gather information from patients with end-stage renal disease to inform a holistic and inclusive intervention that ensures Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients have choice and are involved in their renal therapy journey.

Data collection and analysis

A range of methods were used to enable triangulation of data across multiple sources and perspectives. Thirty-five episodes of data collection, involving one or more of the methods summarised in Box 1, were conducted and recorded (audio or video), depending on the context and participant preferences. Translatability, considering both concepts and language, was explored through analysis of recordings of extensive discussions with language experts, trial interpretation of plain English versions of survey items, back translations of First Nations language interpretations to English and through comparing consistency of response (when a participant provided an extended explanation) with the intended meaning of the item. Acceptability and relevance of both the process of administration as well as the form and content of survey items were explored through collaborative analysis of recorded observations of survey administration with participating language experts and survey administrators as well as reflective discussions with health staff participants. Data from all sources were translated, transcribed and analysed through a collaborative process engaging with participating language experts. NVivo v12 (Lumivero; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo) was used for data management and analysis to support a rigorous and collaborative process, integrating data from all sources. Through an iterative and inductive process key factors influencing acceptability and relevance of both survey process and items as well as translatability were identified, and emerging findings were discussed with participants and refined in response to feedback.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (CA-19-3518) with reciprocal approval from Charles Darwin University HREC (H20061) and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory and Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (HREC 2019-3530).

Results

This study incorporated multiple methods and diverse First Nations language expert and health staff perspectives to develop a deeper understanding of the challenges and considerations in collecting authentic patient experience information through surveys with speakers of four First Nations languages. Key findings common to both surveys included extensive challenges in achieving equivalence of meaning and a lack of congruence between survey methods and First Nations cultural communication protocols and preferences. These limitations of survey methods compromise both the quality of information collected and the cultural safety of the process. The RtC survey tool was extensively modified in response to the relevant findings from this study, and a detailed account of this process will be published separately.

Achieving equivalence of meaning

Achieving equivalence of meaning between the English version and First Nations language interpretations of items and response options was highly problematic across both surveys. Although an initial review by language experts sometimes assessed survey items as possible to interpret, unexpected challenges were revealed when actually trialling interpretation into the target language. Back translation of recordings of the AHPEQS survey, particularly for Central Australian languages, also revealed extensive inconsistencies between the intended meaning and the First Nations language interpretations for multiple items and responses. These ranged from minor omissions of detail to profound differences between translation and the intended meaning in the English version. The following comparison of original English, plain English and Warlpiri versions provides one example:

Original AHPEQS item: I experienced unexpected harm or distress as a result of my treatment or care.

Plain English version (original item modified following repeated consultation with interpreters prior to this study): When health staff were looking after me, I didn’t think I would get hurt, but something they did made me worried or made me feel hurt or sick.

Warlpiri recording on the iPad: When the health staff were taking care of me I knew that I wouldn’t get hurt or in pain but when they couldn’t tell me anything I felt anxious.

Although this item was particularly problematic across all four of the languages explored in this study, inaccuracies in interpretation were identified by language experts for numerous items despite extensive efforts to ensure equivalence of meaning during initial adaptation of the AHPEQS survey for Aboriginal language speakers prior to this study.

Cultural variations in conceptualisations and representations of time and frequency were a common barrier to achieving equivalence of meaning across languages in the surveys. For example, items relating to experience within a specific time-frame – weeks or months – could not be interpreted. Although references to phases of the moon, seasons or events – or a more general term such as ‘recently’ – were suggested as potentially more meaningful, language experts strongly advised that items requiring a response related to a specific timeframe should be avoided if possible. Even when a clear explanation of the required timeframe was achieved in trial of surveys, extended responses indicated that the participant was not confining their response to their experience within the requested timeframe, further illustrating that time-bound constraints on responses were not effective or appropriate.

Response options relating to frequency were also challenging – or impossible – to interpret due to absence of equivalent terms in First Nations languages, including terms such as ‘a little bit of the time’ and ‘a lot of the time’. Even when response options were reduced from five to three such as ‘never, sometimes, always’, equivalent terms did not exist in all languages. Terms such as ‘how long’, ‘how often’ ‘less than’ and ‘more than’ are just a few examples of other quantitative terms that compromised translatability of survey tools.

Culturally specific metaphors or idioms were particularly challenging to interpret, for example ‘spending time’, ‘a fact of life’, ‘prove them wrong’ and ‘brought it on yourself’. English terms that were unfamiliar to interpreters such as ‘excluded’ and ‘perpetrator’ could be interpreted when their meaning was explained in plain English. Many other terms were more challenging when conceptual and/or semantic equivalence in the target language were difficult to achieve, for example ‘treatment’, ‘blood pressure’, ‘unfairly’, ‘rights’ and ‘discrimination’. Such terms (and many others) required extensive discussion with language experts to clarify meaning, and lengthy explanations in interpretation.

A particularly challenging term that does not have conceptual equivalence in First Nations languages is the term ‘too much’. The survey item ‘are you eating too much’ was consistently interpreted as ‘are you eating a lot’ and perceived as a positive condition. This interpretation profoundly changes the meaning of the item and the significance of the response. Even after extensive and multiple discussions an interpretation that captured the intended meaning of ‘excessive food consumption’ remained difficult.

Grammatical discordance between languages, including differences in word order conventions and syntax, such as passive rather than active constructions, were common challenges identified by language experts. For example, cultural constraints on use of questions (see below) are reflected in the absence of grammatical constructions in First Nations languages equivalent to some question forms in English. Although the survey intended for self-administration (the iPad version of the modified AHPEQS) used statement forms for most items (eg ‘I felt like the health staff cared for me’), an interrogative intonation (rising tone at the end of the sentence) was often used in oral recordings in First Nations languages. For a survey intended for administration by someone else such as the RtC survey tool, a question form is a more natural form of communication in English. However, there was often no grammatical equivalent in First Nations languages and these items were interpreted as statements with an interrogative intonation to indicate the speaker was seeking a response. Interestingly, when question forms were interpreted as statements with an interrogative intonation these often reverted to a question form in back translation to English. This masked the lack of congruence between the original and interpreted forms of items, illustrating the critical importance of in-depth collaborative examination of items with language experts to ensure optimal translatability of plain English versions.

The need to assess equivalence of meaning when visual images are used in survey tools was also identified: language experts’ interpretations of the images did not align with the response options they were intended to represent. For example, the facial expression in an image used to illustrate the response option ‘not true’ was interpreted as ‘being frightened’.

Cultural protocols and preferences for seeking and sharing information

Seeking feedback from patients about their healthcare experiences was considered important by participants if the purpose was clearly explained and if sharing their experience would lead to action:

… it makes me feel like I've been heard if I see an outcome, a result (Dianne Gondarra, Yolηu language expert/patient)

Conversely, participants reported that ‘it doesn’t feel good’ when a communication process does not align with cultural protocols. This negative outcome was described by Yolηu language experts as marranamirr rom dhärukku – disrespectful communication:

[this can] also relate to using language in a different environment – and the rules of speaking are very strong back at home but here [using a survey in a hospital environment] that's taken out – and the language and rules that apply don't match … the artificial form of communication in survey methods dismantles proper processes of communication from a Yolηu perspective. (Dikul Baker, Yolηu language expert)

There are profound differences between the cultural and linguistic context in which the surveys were developed and First Nations participants’ cultures and languages. These differences influenced both the acceptability of survey tools and the authenticity of information collected through this method. For example, there are communication protocols governed by context and relationships that influence the acceptability of direct questions for cultural groups participating in this study:

Why is this person asking me all these questions and questions and questions? …. it doesn’t feel good, and then you get less, people will stop wanting to say anything because they get a bit over it. (Julie Anderson, Yankunytjatjara language expert)

An approach to seeking information that does not align with cultural protocols can cause discomfort and disengagement – and opportunities for understanding what needs to change can be missed.

An untrue story …

Cultural communication protocols also impact on authenticity of responses: participants described a cultural imperative to provide a positive or expected response, particularly in situations of unequal power. In the context of using survey methods to collect patient experience information, this could result in reluctance to be directly critical to a stranger or about a group to which the survey administrator is perceived to belong. For example:

Surveys are very hard … people will answer just to make you happy … That's what you get from a survey – an untrue story. (Läwurrpa Maypilama, Yolηu language expert)

Health staff involved in survey implementation also questioned the authenticity of patient experience information captured through the survey process. For example, responses to the AHPEQS survey in one hospital were overwhelmingly positive – and inconsistent with patient feedback obtained through other mechanisms such as the patient complaint process:

Every single person literally has said ‘always, always, always’… And it can't be right … It’s a waste of resources, it's a waste of time. (Survey administrators, Central Australia)

They don’t want the deep story …

Restriction to a limited range of responses that does not allow participants to share more extended and nuanced accounts, as well as contextual variations in their experience, was also a common concern. This restriction in opportunity to share details of experience influenced the acceptability of survey methods:

… they don’t want the deep story … ‘no, yes, no’ – this has no story … wasting everyone’s time. (Dianne Gondarra, Yolηu language expert/patient)

For me, I think this is very unhealthy for everybody who is going to come across this (survey) … it doesn’t allow for the person being interviewed to express their whole story, so it leaves them with all these triggered feelings from this unhealthy way of information collecting. (Dikul Baker, Yolηu language expert)

This limitation was clearly illustrated when participants shared more detailed accounts of their experience that contradicted the response selected from the survey options. For example, when trialling the RtC survey a language expert who is also a renal patient responded ‘all the time’ to an item about staff keeping her information private from other patients – then shared multiple experiences of failure to ensure privacy during further discussion.

The opportunity to take action in response to feedback – the point of collecting patient experience data – is also limited when details of experience are not captured:

We can't implement, you know, like, ‘Did you feel cared for?’ even if someone said, ‘No, I didn't feel cared for’, there's no context around why didn’t you feel, in what aspect of your care? ... I don’t think those questions [are] getting anything near the information that we should be getting. It’s not useful. (Survey administrators, Central Australia)

Engaging with the surveys often elicited in-depth responses from participants about their experience and also ideas for what needs to change. However, such information cannot be recorded at the item level of the survey tools reviewed in this study as the only option for free text is at the end of surveys. This limits the extent to which information that patients wish to share about their experience can be captured – and acted upon.

Nothing beats conversation with the right person …

A conversational approach in seeking information, rather than reading out and interpreting survey items in their original form, was strongly advocated by participants. Such an approach allows participants to provide more detailed and authentic information about their experiences:

[the opportunity] to tell the full story – make it meaningful – not to ask questions and we give you just yes and no answers – without the full story ... like it's just your story. (Dianne Gondarra, Yolηu language expert/patient)

We don’t want to be always asked questions just so that they can tick a box, yes or no. We need to be heard and have our reality understood. For people to listen deeply: puruanyani yirri yirrili – listening carefully to understand. (Warlpiri language expert)

Language experts argued that capturing patient experience information through ‘their natural form of communication’ also enables explanation, checking intended meaning has been understood and the opportunity to ‘capture what’s important to patients’.

Adapting communication to individual needs – not ‘one size fits all’ …

Variations within First Nations languages across locations and age groups also influenced the extent to which an interpretation was meaningful and appropriate. First Nations languages have evolved over time in response to external influences before and since colonisation, such as contact with other cultural groups and more recently social media. Reflecting these influences, both the forms of language as well as communication protocols can vary depending on the age group of the speaker:

… what might be a reality for some age groups in communication might not be a reality for other groups … (Dikul Baker, Yolηu language expert)

In face-to-face administration of a survey, an experienced interpreter can facilitate appropriate and effective communication through adapting their form and style of language to suit each individual. However, when surveys were administered through recordings in First Nations languages, adaptation to individual communication needs was not possible. This limitation was evident in the range and representation of language options on the iPad-based version of the AHPEQS. For example, the form of Arrernte (Central Arrernte) used in the recordings is not specified and language experts suggested this may not be appropriate or meaningful for speakers of Eastern Arrernte. Multiple forms of other First Nations languages that might not be understood by all speakers from that language group were also identified.

Consequences for interpreters

When survey methods are not consistent with First Nations communication protocols and needs, this results in what one Yolηu language expert described as mel-manapanawuy dhärukku rom – a communication process that conflicts with the identity and rights of a First Nations language speaker. When a patient participates in a survey – following their cultural protocols to respond even when they don’t fully understand and suppressing full expression of their experience – this was described by a language expert as a form of ‘silent coercion’. The information collected through such a process has no value in achieving the purpose of a survey intended to collect authentic patient experience information to inform health service improvements. An ineffective process that doesn’t lead to action that benefits patients is ηitjmiriw.

The task of interpreting the English versions of surveys into First Nations languages was complicated by multiple and complex conceptual and linguistic factors. These multiple barriers to achieving equivalence of meaning – as well as respect for cultural communication protocols and preferences – place inordinate demands on interpreters. When the interpreter is forced to communicate in ways that are not culturally and linguistically congruent:

[it] makes the interpreter seem incompetent and damages their professional reputation … when the problem is actually the survey. (Dikul Baker, Yolηu language expert).

To ensure a culturally safe and effective approach for all those involved in collection of patient experience information, participants strongly advocated for a collaborative approach engaging local cultural and language experts working with health staff and researchers through all stages of planning, development, implementation and evaluation:

Work together – find out the way together … because if you want to know about a patient’s experience and what’s important to them then you need to know the population … (Yolηu language experts)

Discussion

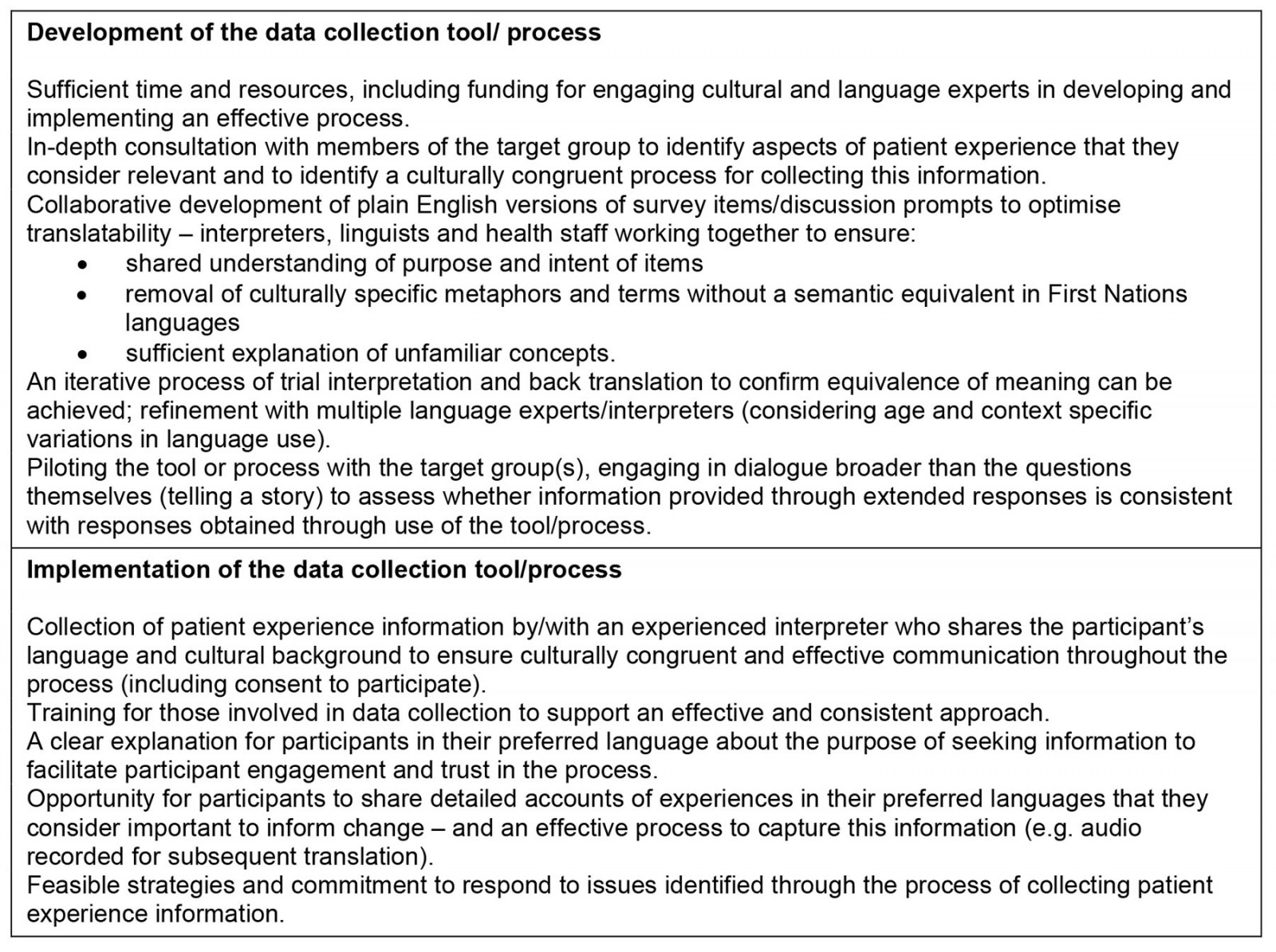

Serious challenges in achieving equivalence of meaning as well as discordance between survey methods and First Nations cultural and communication protocols were identified through critical review of two survey tools. These limitations have implications for the quality of information collected, and resulted in frustration and distress for some of those engaging with the survey including administrators, interpreters and respondents. Insights from First Nations language experts captured through collaborative critical review of survey tools have shaped the findings and are a particular strength of this study. This approach supported a deeper understanding of challenges and considerations in collection of patient experience information from the perspectives of speakers of First Nations languages themselves. Key considerations for culturally and linguistically responsive collection of patient experience information, drawing on the findings of this study and informed by previous research, are summarised in Box 2. These findings may be relevant to any approach to data collection, including alternatives to survey methods, as discussed below.

Challenges in achieving equivalence of meaning when adapting a survey for other language and cultural groups have been well documented13,27. Similarly, evidence from this study demonstrated that translatability of survey items was extensively compromised by the use of metaphors specific to Western culture, English words that are familiar but used with different meaning, English terms with no equivalent in First Nations languages and grammatical discordance between languages. Multiple translations, back translations and in-depth discussions between all members of the research team were necessary to achieve a sufficient level of confidence that equivalence of meaning had been achieved.

Even when translated accurately, items and responses did not always have equivalent meaning for participants due to differences in cultural and conceptual knowledge and perspectives. Familiarity and relevance of concepts in survey items were influenced by cultural variations in conceptualisations of time, understandings about the body, health and illness as well as experience with health systems and services. When shared understanding of concepts is incorrectly assumed, the challenge for translation and risk of miscommunication is high. Even for First Nations Australians who have a high level of English fluency, when conceptual understandings are not shared effectiveness of communication is compromised28. Providing pictures to illustrate concepts in some items, such as forms of treatment, was identified by language experts as a strategy to reduce the need for more extended explanations. However, cultural differences in visual literacy29 were also evident in this study, confirming the importance of considering culturally specific interpretation of visual representations to ensure equivalence of meaning is achieved.

Some survey tools reviewed in this study had previously undergone an intensive modification process for use with speakers of First Nations languages. For example, the process of adapting the AHPEQS survey continued over a number of years and involved extensive time and resources. Similarly, sections of the RtC tool that had previously been through a rigorous adaption process for use with speakers of First Nations languages remained challenging. Back translation is considered important to confirm equivalence of meaning11 and inadequate implementation or omission of this process may have contributed to challenges in the surveys reviewed in this study. Although back translation can confirm linguistic equivalence, this is insufficient to ensure conceptual equivalence across different cultural contexts30. An iterative and collaborative process engaging multiple language experts as well as pretesting and assessment of the survey with the intended cultural group30, requiring extensive time and resources, was confirmed through our findings as essential to reveal and resolve challenges in achieving equivalence of meaning.

Although a rigorous and collaborative adaption process may improve relevance and translatability, a lack of congruence between survey methods and First Nations cultural protocols and preferences for seeking and sharing information cannot be overcome, even with implementation of best practice in survey development. As the findings of this study demonstrate, the lack of opportunity to share the ‘full story’, discomfort with direct questions and communication protocols that preclude negative or critical responses constrain the authenticity of the information obtained when using survey tools. Like that of Walmsley et al19, this study found that direct questions are not aligned with culturally respectful ways of eliciting information. As found by Mithen et al18, closed survey questions may result in answers that do not accurately reflect the patient experience. Selecting the response the patient thinks is expected can be a cultural sign of respect31 or, as language experts in this study also suggested, a sign the meaning is unclear or a way to hasten the interaction. A cultural imperative to agree is also a critical consideration for seeking consent for participation in any form of patient experience data collection. This study highlighted the importance of determining participants’ preferred language and engaging an appropriate interpreter if needed before commencing the information and consent process, so that a clear understanding of the purpose and nature of data collection can enable genuinely informed consent.

The findings of this study clearly demonstrate the limitations of survey methods in engaging consumers through ‘accessible, culturally responsive and safe processes’25 (p. 15). Instead, participants recommended alternative ways of collecting data that are linguistically and culturally congruent and therefore more likely to provide authentic data that can inform quality improvement. Based on the findings of this research, providing the opportunity to tell a story in their preferred language would not only improve the quality of data, but would also improve First Nations people’s experience of providing feedback on their care. Although engaging with surveys does have the potential to elicit in-depth responses, current designs that require participants (or administrators) to add written comments in English are not responsive to the needs of many speakers of First Nations languages32. An option to audio-record extended responses rather than limiting response options could provide in-depth qualitative data from which quantitative data can also be extracted. Engagement of relevant cultural and language experts would remain crucial to ensure the integrity of this approach.

Alternatively, gathering in-depth patient experience data using culturally congruent communication processes in participants’ preferred languages is relatively feasible in terms of both the time and resources required compared to adapting existing survey tools. Such an approach can facilitate both acceptability of the process and the quality of information collected18. A face-to-face conversational approach was strongly advocated by participants in this as well as other studies6, allowing the interviewer to clarify concepts, patients to share detailed and nuanced accounts of experience that matter to them and health staff to understand what needs to change. The Patient Stories toolkit33 is one example of a tool that aligns with these preferences. However, only relevant cultural and language experts can ensure any approach is responsive to cultural protocols as well as cultural and individual communication needs.

The findings from this study confirm the crucial importance of engaging local cultural and language as well as content experts from the beginning and throughout development and implementation of patient experience data collection processes; this is not only necessary for authenticity, but also as a decolonising endeavour6,8,22,23. Importantly, the integrity of any approach to patient experience data collection relies on effective strategies to address identified concerns at both individual and system levels.

Box 2: Key considerations for collecting authentic patient experience information with speakers of First Nations languages

Limitations

This exploratory study focused on only two survey tools of particular relevance to speakers of First Nations languages in the NT. As well, the number of First Nations language experts engaged in the study and range of languages explored were limited by available time and resources. Therefore, relevance of the findings to other cultural and language groups or locations cannot be assumed. However, the learnings generated through this study can be assessed for relevance with other First Nations populations in future development of culturally and linguistically congruent approaches to collection of authentic patient experience information. To support deeper understanding of feasible and effective alternatives to survey methods a subsequent collaborative study is being conducted, informed by the findings of this study, to trial and evaluate a conversational approach for gathering patient experience information with First Nations language speakers.

Conclusion

The quality of information obtained through patient experience data collection – and the cultural safety of the data collection process – are crucially important in ensuring that First Nations Australians genuinely inform health service development and evaluation. Profound implications for the acceptability of a survey tool as well as data quality arise from differences between First Nations’ cultural and communication contexts and the context within which survey methods have evolved. When data collection processes are not linguistically and culturally congruent there is a risk that patient experience data is inaccurate, misses what is important to First Nations patients and has limited utility for informing relevant healthcare improvement. Engagement of First Nations cultural and language experts is essential in all stages of development, implementation and evaluation of culturally safe and effective approaches to support speakers of First Nations languages to share their experiences of health care and influence change.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the First Nations language experts who shared their knowledge through their participation in this project, including those who are authors of this article as well as those who contributed to data collection: Lorna Wilson (Pitjantjatjara), Kathleen Wallace (Eastern Arrernte), Maratja Dhamarrandji (Djambarrpuyηu), the late Jamie Thorne (Djambarrpuyηu), Janey Wells (Pitjantjatjara) and Joel Liddle (Eastern Arrernte). We also thank Christine Spencer as well as other First Nations language experts and health staff at Alice Springs Hospital for their valuable contributions and NPY Women’s Council for their assistance with engaging language experts in project activities.