Introduction

A sustainable rural workforce plays a crucial role in the healthcare system of any country where rural health access is challenging, including developed countries1-7. However, recruiting healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas remains a persistent challenge8,9. Factors such as the insufficient presence of healthcare professionals in rural areas, limited training prospects, concerns about social and professional isolation and restricted job opportunities for significant others impact the decision-making of current and aspiring healthcare professionals10-15. Australia, like other countries, has undertaken proactive measures to enhance the rural healthcare workforce in response to the current crisis16. These measures include diverse career growth opportunities, financial incentives such as moving expenses and bonuses, and specialised positions aimed to bridge this workforce gap17.

In 2010, the WHO proposed a worldwide policy to improve access to health workers in remote and rural regions by enhancing retention18. The recommended strategies included educational initiatives, regulatory measures, financial incentives, and personal and professional support18. Various policies, initiatives and studies have been employed to facilitate the recruitment and retention of healthcare professionals in rural and underserved areas. These include the establishment of rural clinical schools, relocation allowances, financial bonuses, recruiting students from local rural and remote areas, creating conducive conditions for health providers, in-kind benefits (free accommodation or vehicle), relevant rural learning experiences, and incentive-based strategies with regional, state or provincial government backings19-24.

Professional identity formation is crucial in healthcare education, shaping how students think, act and feel as professionals25. It helps them find meaning in their work and supports long-term wellbeing. Professional identity formation involves developing values, attitudes and behaviours, and aligns with professional norms26. In rural health care, a strong professional identity can improve retention by fostering a sense of connection and commitment26. Strategies to support professional identity formation include mentorship, reflective practice and a supportive learning environment25.

The Australian Government’s commitment to sustained funding in rural medical education aims to enhance the likelihood of rural area retention among medical students upon graduation11,27,28. Rural clinical schools provide intensive clinical training to undergraduate medical students, grounded in practical experiences within hospitals and community-based settings within a rural and remote region20. These schools offer high-quality medical education in rural Australia, allowing students to complete their entire medical program at rural campuses in various locations20,29.

Extensive research associated with undergraduate medical health professionals has extended to other healthcare professionals27,28,30,31. This has led to the introduction of the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program, which aims to improve retention and recruitment of medical, nursing, allied health and dental professionals in rural and remote Australia32.

For nursing and allied health professionals, such as dentists, dieticians, physiotherapists and Aboriginal Health Workers, workforce initiatives have primarily focused on rural communities cultivating their own healthcare professionals33,34. Research has underscored the importance of augmenting students’ clinical exposure in rural settings13,14,16. Policymakers have recognised the need for more ‘high calibre’ extended rural placements for nursing and allied health students to bolster rural workforce recruitment and retention35-37. Research has demonstrated that a favourable rural placement encounter enhances a student's willingness to return to practice in rural areas and influences future career intentions35,37-39. The positivity of a rural placement experience often stems from the feeling or sense of belonging during the placement period40. Scholarly work focusing on nursing students suggests sense of belongingness significantly impacts the learning journey of nursing and midwifery students, and a sense of belonging remains a critical factor to be considered40-43.

Levett-Jones et al define belongingness as an intrinsically personal and contextually influenced phenomenon that develops in reaction to the extent to which an individual perceives (1) being secure, accepted, included, valued and respected by a specified group; (2) being connected with or essential to the group or community; and (3) an individual’s professional and personal values align with those of the group40. The concept of belonging is described as an individual's engagement with a group or framework that is characterised by feelings of being appreciated, required or embraced by a group31. Several studies have sought to explain the relationship between positive clinical placement experiences and a sense of belonging. For example, supportive learning relationships within a clinical team are key for healthcare students to feel they have a place within that team44.

However, limited research explores the relationship between a sense of belonging from community involvement and activities and its contribution to the future rural and remote workforce. Therefore, workplace relationships are critical both inside and outside the workplace44,45. Developing a sense of belonging within the community environment is vital. This scoping review aims to explore what events and experiences influence medical, nursing and allied health students’ sense of belonging in rural and remote communities while on clinical placement. For this review allied healthcare professionals who undertake rural placements include nutritionists and dietitians, occupational therapists, medical radiation scientists, diagnostic radiographers, speech pathologists, physiotherapists, pharmacists, podiatrists, dentists and social workers as outlined by Allied Health Professions Australia46. The term ‘allied health’ will be used from here on unless otherwise specified.

Methods

Study design

A scoping review was undertaken according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scoping review methodology47 and using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta Analysis for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines48,49. The JBI System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (SUMARI) is an online tool designed for a wide range of healthcare professionals, including nurses, to assist in conducting literature reviews by guiding them through each step, from planning to final report writing as methods to improve evidence-based practice and patient care50. Overall, this approach was appropriate due to the significant body of knowledge on sense of belonging within the clinical environment, contrasted with the limited understanding of students’ sense of belonging outside the clinical environment51,52. Therefore, the purpose of the scoping review was to broadly examine the literature to identify, map and provide key insights and potential gaps of the phenomenon48,53.

Search strategy

A preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE, JBI Evidence Synthesis and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews revealed no current or in-progress scoping reviews focused on our aim. With the support of a content specialist librarian, between 1 February and 29 February 2024 we searched five electronic databases. The timeframe for published articles was set between 1995 and 2024, aligning with the introduction of the rural clinical schools through the Australian Government’s Rural Clinical Training and Support program19 and the 2010 WHO policy to enhance the rural workforce18. The databases searched were CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), APA (American Psychological Association) PsycInfo, PubMed (via Ovid), ProQuest and Informit Health Collection. We also hand-searched the reference lists of all articles extracted for full-text review.

Search terms

Key search terms included, but were not limited to, "Students, Health Occupations" OR 'Allied Health Personnel" OR 'Dentist' OR "Nurse" OR "Nutritionist" OR "Occupational Therapist" OR "Pharmacist" OR "Physical Therapist' OR "Physician" OR "speech pathologist" OR "social worker" OR "Aboriginal health practitioner' AND 'Placement' OR 'work integrated learning' AND 'Rural' OR 'Remote' AND 'Social*' OR 'Communit*' OR 'Connect*' OR 'Belong*'. Additional keyword combinations used in this review are provided in Appendix I. An exemplar of the search strategy used in PubMed is provided in Appendix II.

Eligibility criteria

We included reports on rural and remote student placement participant groups, specifically those undertaking a baccalaureate level (or higher), health professional program. We considered peer-reviewed primary research with quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods designs. Grey literature was excluded to ensure the inclusion of rigorous and peer-reviewed evidence. Both Australian and international research written in English were included. Articles were excluded if participants were not studying at a baccalaureate level (or higher) health professional program, if placement locations were not identified as rural and remote or if sense of belonging only related to supervisor–supervisee relationships within the clinical environment. Specific inclusion criteria also encompassed key concepts and contexts outlined in detail.

Concept

We included reports on students undertaking or having completed clinical placement, classified based on the international classification of health workers by WHO54. This included nursing, medical, dental, occupational therapy, pharmacy, physiotherapy, paramedical, dietetics and nutrition, and social work students. Publications were included if they discussed events and experiences surrounding a sense of belonging from community activities during clinical placement.

Context

Publications specific to the Australian context commonly outline the geographical location of rural and remote location based on the Modified Monash Model (MMM) classification or its precursors if written prior to the commencement of MMM55. If the MMM was not clearly outlined, a clear definition of the study’s location was required, cross-checking against the MMM classification. As this review focused on research conducted within the rural and remote environment, the classification of ‘rural’ and ‘remote’ may differ to that of an Australian context. For this reason, this review included countries listed in the OECD that classify ‘rural’ and ‘remote’ similarly to the Australian context56. International studies must have reported the location as being considered rural and remote, and use similar typology as defined of this geographical nature by OECD.

Source of evidence selection

All potentially relevant articles were imported into EndNote X9 for review. After removing duplicates, articles were collated and uploaded into JBI SUMARi57. To ensure all duplicates were removed, the EndNote duplicator function was used along with the de-duplicator software due to sensitivity issues within EndNote58. Titles and abstracts were initially reviewed by three researchers (JE, DT and LR) based on the inclusion criteria, with full text of selected articles reviewed with the JBI SUMARI platform. Two reviewers (JE and DT) then independently appraised each study, with a third reviewer (LR) consulted for any conflicts. Reasons for exclusion of articles at the full-text stage were recorded, such as ineligible population (eg not healthcare students), ineligible sense of belonging (being clinical and not community focused) and ineligible study design (eg reviews).

Data extraction

A data extraction tool was created in JBI SUMARI and replicated into Microsoft Excel to facilitate easier manipulation and analysis of the data. Extracted data included author, publication year and location, study design, participant population, sample size, definition of ‘rural’ and ‘remote’ and of the aim of the article. Outcomes, measurement tools and data analysis methods were also extracted, along with descriptive and inferential statistics.

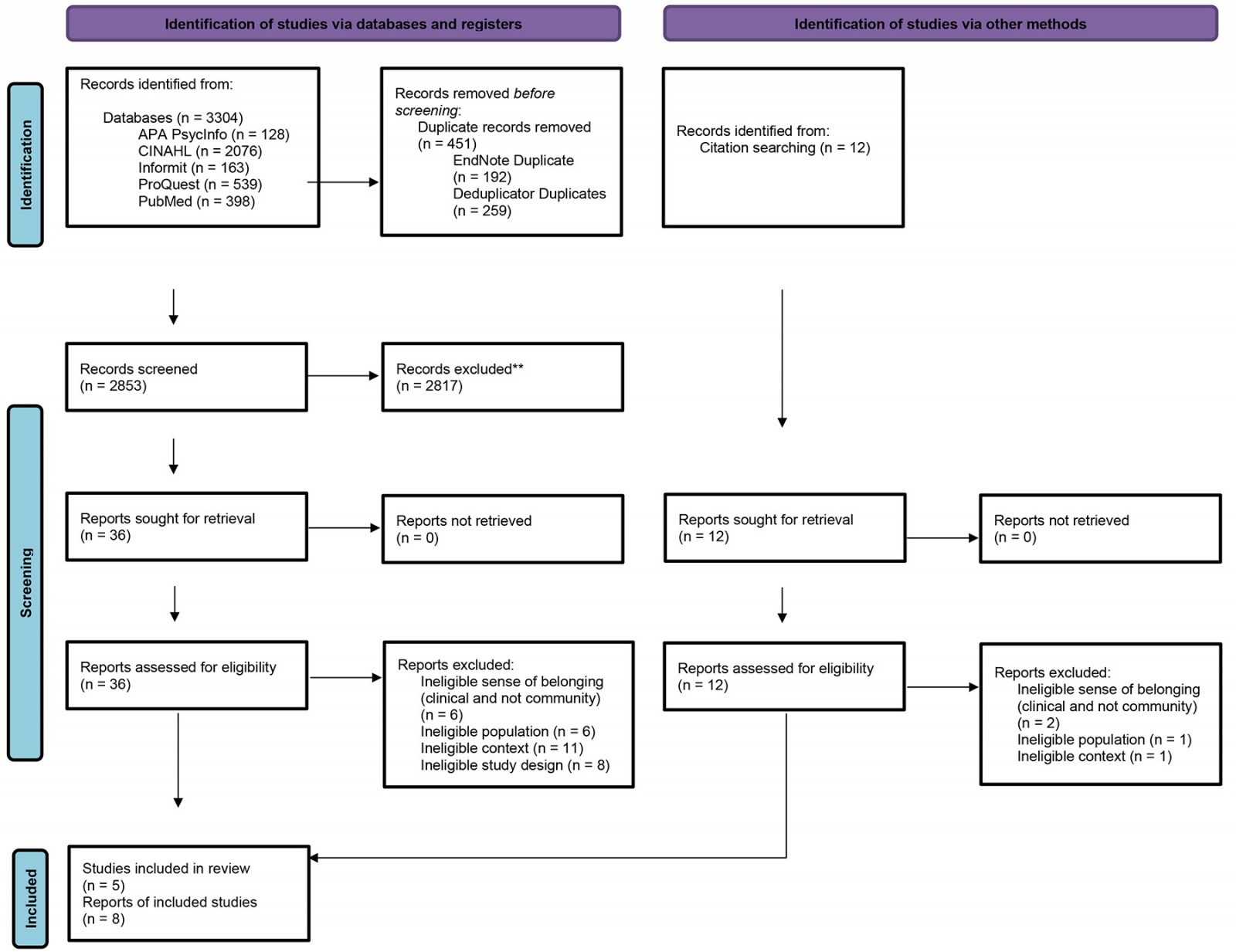

The results and discussions were reviewed by the authors to identify the depth of the reported events and experiences. A total of 3316 records were identified. After removal of duplicates (n=451), title and abstracts were screened, excluding 2817 records. The remaining 48 articles underwent full-text screening, resulting in 13 articles deemed eligible based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

Quality appraisal

Two researchers independently assessed the included articles using the relevant JBI critical appraisal tools59. These tools include the JBI Qualitative Research tool, which is designed to assess the methodological quality of qualitative studies by evaluating aspects like congruity between research methodology and objectives. Each criterion is scored as ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’, helping to determine the overall trustworthiness and relevance of the study50. The second tool used was the JBI Analytical Cross Sectional Studies tool, which evaluates the quality of cross-sectional studies by examining criteria such as the clarity of inclusion criteria and the validity of exposure measurements. Similar to the qualitative tool, each criterion is scored as yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’, providing a comprehensive assessment of the study's methodological quality50. After each article was assessed, any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. The quality of each article was scored as high, moderate, low or excluded. Overall, the studies were generally of low quality, with common issues including unclear key potential confounders, lack of reference to data saturation in qualitative studies, and omission of philosophical perspectives. Quantitative studies often had small sample sizes, leading to a higher risk of biased responses. Among the included studies, five were of moderate quality and eight were of low quality. There were no high-quality studies. Table 1 and Table 2 include detailed quality criteria.

Table 1: Methodological quality† assessment using the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Research tool

| Author (year) | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | Overall quality | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradley et al (2020)60 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Low | Included |

| Crossley et al (2023)61 | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Low | Included |

| Dalton (2004)62 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Low | Included |

| Denz-Penhey et al (2005)63 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Low | Included |

| Fisher et al (2018)64 | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Low | Included |

| Heaney et al (2004)65 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate | Included |

| McAllister et al (1998)66 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Low | Included |

| Smith et al (2018)16 | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate | Included |

| Sutton et al (2016)37 | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate | Included |

| Walker et al (2022)67 | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Moderate | Included |

† Quality criteria: A: Congruity between philosophical perspective and research methodology? B: Congruity between methodology and research question/objectives? C: Congruity between methodology and methods used to collect data? D: Congruity between methodology and the representation/analysis of data? E: Congruity between methodology and the interpretation of results? F: Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? G: Researchers culturally/theoretically stated? H: Influence of the researcher /research addressed? I: Research conducted ethically/ethical approval noted? J: Conclusions drawn report flow from analysis/interpretation of data?

Table 2: Methodological quality† assessment using the Joanna Briggs Institute Analytical Cross Sectional Studies tool

| Author (year) | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Overall quality | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elliott et al (2023)68 | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | Unclear | No | Unclear | Yes | Low quality | Included |

| Webster et al (2010)69 | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | Yes | Moderate quality | Included |

| Wolfgang et al (2019)70 (mixed methods) | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | No | Yes | Yes | Low quality | Included |

† Quality criteria: A: Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? B: Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? C: Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? D: Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? E: Were confounding factors identified? F: Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? G: Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? H: Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

NA, not applicable.

Data analysis

Researchers used tabular, descriptive and narrative approaches to present the extracted data. Due to the heterogenous nature of the studies, a narrative analysis approach was adopted to identify and synthesise themes. Following Leggo’s method71, each article was read multiple times to derive significant statements and meanings. Words and phrases were coded inductively to identify emergent themes, generating an inventory of subthemes related to participants’ experiences in community activities72. The research team continually refined these themes through discussion, to ensure accuracy and consistency. Leggo’s steps of thematising and expanding71 were used to assess and highlight features commonly associated with a sense of belonging from student placements. The codes were then categorised into broader domains, resulting in three main themes aligned with the review’s aim. This rigorous process ensured a comprehensive understanding of the data.

Ethics approval

This study is a review of previously published literature and did not engage any human participants or collect primary data. Accordingly, no research ethics approval was required.

Results

Among the 13 peer-reviewed articles, two were quantitative studies involving surveys and questionnaires68,69, 10 were qualitative studies with interviews or focus groups16,37,60-67 and one was a mixed-methods study70. A summary of review characteristics extracted is displayed in Table 3.

All studies were conducted in Australia, with locations including Newcastle64,65, New South Wales70, Queensland67, Sydney66,69, Tasmania62, Victoria60, and Western Australia61,63. Elliott et al68, Sutton et al37 and Smith et al16 all defined their locations as being of non-specific location and were aimed at students across Australia.

Participant populations included students from various healthcare professions. Some studies focused on specific professions like nursing62,65,69 or nursing and midwifery67, medical students63,68, allied health students70 and nutrition and dietetics students65. Five studies included a mix of professions including nursing, medical, nutrition and dietitians, occupational therapy, speech pathology, physiotherapy, pharmacy, podiatry, medical radiation science, diagnostic radiography, social work, Aboriginal health and dentistry16,37,60,64,66.

Table 3: Characteristics of included articles

| Author (year) | Study location and year(s) | Study design | Participant population (sample size) | Definition of ‘rural’ and ‘remote’ | Study aim | Measurement tools / data analysis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradley et al (2020)60 |

Victoria, Australia 2019 |

Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

Nursing and allied health students (occupational therapy, social work, medical imaging, physiotherapy) (n=18) | Not provided |

To investigate nursing and allied health students’ experiences in rural and regional Victoria, focusing on factors influencing placement satisfaction and wellbeing. Outcome: Identity actionable insights to improve the rural placement experience. |

Thematic analysis | Themes: enjoyment of rural life, supportive workplaces, diverse clinical exposure, financial stress, travel challenges, work–life balance, isolation, stressful situations and communication issues with universities. |

| Crossley et al (2023)61 |

Western Australia 2015–2021 |

Qualitative longitudinal study Semi-structured interviews |

Nursing students (n=10 included in final analysis) | Not provided | To better understand personal and professional decision-making around rural nursing practice intentions and subsequent rural employment and retention. | Thematic analysis | Themes: participants’ satisfaction with rural placements; challenges; rural intention. |

| Dalton (2004)62 |

Rural Tasmania Completion of study timing not clear |

Qualitative Participant observations, field notes, interviews and reflective journalling |

Nursing students (no participant number given) | Not provided | To explore how the experiences of nursing practice in a rural setting influenced the way undergraduate students shaped their professional identity while on clinical placement. | Hermeneutic circle framework | Themes: navigating rural spaces; time as a source of conflict; developing a rural nurse identity. |

| Denz-Penhey et al (2005)63 |

Western Australia 2003–2004 |

Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

Undergraduate medical students (n=28) | Not provided | Articulates parallel findings from three different approaches to student placements (students based long term in one centre, students based in one centre with short-term rotations and week rotations without a home base. |

Thematic analysis Grounded theory approach |

Themes: home based preferences – academic benefits; contributions to clinical team; social benefits; rotations from a home base / without a home base. |

| Elliott et al (2023)68 |

Australia June–July 2022 |

Cross-sectional survey Questionnaires |

Medical students (n=107) | MMM geographic categories |

To determine factors that impact the overall medical student experience during rural placements. Outcome: To assess factors impacting student experience on rural placements, a cross-sectional survey, known as the Australian Rural Clinical School Support Survey, was conducted, which was completed online by medical students across Australia. |

Descriptive statistics | Participants expressed high satisfaction with clinical supervisors and education but noted limited accessibility to health services. Satisfaction with rural placements was significant, with participation in extracurricular activities (57.7%); sport (55.6%), tutoring, volunteering, work opportunities and additional teaching (22.2%). However, dissatisfaction was noted with school wellness activities. Financial insecurity was noted. |

| Fisher et al (2018)64 |

Newcastle (Australia) March–May 2014 |

Qualitative Mixed methods |

Medicine, nursing, nutrition and dietetics, occupational therapy, medical radiation science, diagnostic radiography, speech pathology, physiotherapy, pharmacy and podiatry (n=95) | None provided | The aim of this study was to investigate whether the program was adding to the students’ rural health placement experiences based on perceptions of both the students themselves and University of Newcastle Department of Rural Health staff. | Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, SPSS v22, descriptive statistics. NVivo v10 qualitative data analysis software | Themes: enhancing work readiness and employability; expanding professional practice capabilities; building confidence and showing motivation, and better understanding the nature of rural practice (exposure to rural characteristics). |

| Heaney et al (2004)65 |

Newcastle (Australia) 2002–2003 |

Qualitative Focus groups Exploratory study |

Nutrition and dietetics students (n=23) | None provided | The study aimed to identify those factors that influence the decision of a dietitian to consider working in a rural area. | Coding assisted using the N6 qualitative data analysis program | Themes: job prospects; rural lifestyle (laidback environment); comfort zones (size of town); support networks; promotion opportunities/professional development; type of work/work role; rural needs; and time frame. |

| McAllister et al (1998)66 |

Sydney 1991–1996 |

Qualitative | Social work, physiotherapy, speech pathology, medicine, nursing, Aboriginal health, occupational therapy, medical radiation, rehabilitation, dentistry, pharmacy students (n=92) | None provided | The major aims of the project were to provide students with information about rural health and rural careers and to provide exposure to rural practice early and regularly throughout their education. | Content analysis – coding | Themes: friendly and welcoming environment; relaxed lifestyle; sporting as social activities mentioned; barriers (limited funding + resources + continuing education; Isolation; lack of privacy). |

| Smith et al (2018)16 |

Australia July 2014 – November 2015 |

Qualitative |

Undergraduate health students (unclear of inclusion number) Nursing and midwifery, medical students, allied health students (including dentistry, pharmacy, nutrition and dietetics, physiotherapy, speech pathology) |

MMM geographic categories | The aim of the qualitative study was to provide an understanding of the lived experiences of students undertaking placements in various non-metropolitan locations across Australia. In addition to providing their suggestions to improve rural placements, the study provided insight into factors contributing to positive and negative experiences that influence students’ future rural practice intentions. | Manual thematic analysis and computerised content analysis using Leximancer software | Themes: ruralisation of students’ horizons, preparation and support; rural or remote health experience; rural lifestyle; socialisation and interaction; community engagement; cultural awareness. |

| Sutton et al (2016)37 |

Australia Completion of study timing not clear |

Qualitative Interviews and focus groups |

Nursing, midwifery and allied health (n=26 student participants) | MMM geographic categories | To provide in-depth perspectives on how allied health students, nursing students and early-career practitioners of these disciplines construct their understanding of rural practice and gain insight into how their lived experiences influenced their knowledge, perceptions, feelings towards, attitudes about rural and remote practice and, ultimately, about their behaviour in relation to taking up a rural and remote clinical position. |

Descriptive statistics Thematic analysis |

Themes: connection to people, places and communities; work–life balance; limited socialising in rural towns; future career pathway. |

| Walker et al (2022)67 |

Queensland (Darling Downs/South West Hospital and Health Service) (July–November 2020) |

Qualitative inductive approach Semi-structured interviews |

Nursing and midwifery students (n=17) | MMM geographic categories | To understand the benefits and challenges of rural nursing and midwifery placements for students, and to explore factors that influence positive clinical placement experiences. |

Inductive process Codes, subthemes and themes generated |

Themes: supervision and support; engaging with a rural community; placement type and duration influence on rural placement experience; future rural career intentions. |

| Webster et al (2010)69 |

North Sydney 2009 |

Cross-sectional study Pre- and post-clinical placement questionnaire Five-point Likert scale and four short-answer questions |

Undergraduate nursing students (n=8) | Not defined | This article draws on questionnaire findings and analysis of students’ comments to demonstrate the aspects of rural placements that were effective in engaging students in the learning process. It also examined how a primary healthcare clinical placement in Aboriginal communities can provide nursing students with a rich and varied learning experience and an insight into the complex aspects of rural life including Aboriginal health. |

SPSS t-test Content analysis with findings organised into themes |

Significant differences in pre-perceptions and post-perceptions about rural placement (p<0.001 level). Themes (quantitative): support for learning, feeling part of the clinical team, feeling valued for their contribution to patient care and obtaining diversity of clinical experience. Themes (qualitative): community lives, cross-cultural awareness, professional relationships, clinical practice, social life, structural issues. Confidence increased after placement. |

| Wolfgang et al (2019)70 |

New South Wales May 2011 and June 2016 |

Longitudinal study (ongoing). Mixed methodology End-of-placement survey, semi-structured individual interviews and postgraduate survey Survey via SurveyMonkey (five-point Likert scale) |

Allied health students (n=394 did end-of-placement survey; n=275 did at least one survey) – enrolled in undergraduate bachelor degree programs of medical radiation science (which includes diagnostic radiography, nuclear science and radiation science), nutrition and dietetics, occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech pathology Students doing semester-long, short-term or year-long attachments |

MMM geographic categories | To determine the effect of immersive placement experience on rural practice intentions and to compare outcomes between students from a rural versus an urban background. |

Microsoft Excel Analysis: SPSS software Wilcoxon signed-rank test Mann–Whitney U-test Qualitative content analysis to short answers – codes and themes found. NVivo software used |

Themes: immersed rural supported placement experience; immersed interaction in rural life with other students and immersed interaction in the rural community. |

MMM, Modified Monash Model

Three prominent themes emerged from the literature. The three themes were rural environment and the formation of a rural identity, social isolation and community activity engagement.

Rural environment and the formation of a rural identity

Over half (n=8) of the articles examined the relationship between students’ rural and remote placement experience and the welcoming nature of community members. Bradley et al60, Crossley et al61, McAllister et al66, Smith et al16, Sutton et al37 and Wolfgang et al70 all noted the positive sense of belonging felt when the community appeared welcoming, positive and friendly. Simple greetings like ‘hello’ on the street was central to this sense of being welcomed. Bradley et al asserted that being recognised in town as a student further enhanced this sense of belonging60. Fisher et al postulated the need to understand rural practice characteristics, but did not elaborate on what this entailed64. Data provided surface-level insights into the laid-back65 and easygoing community66 nature of rural communities. Dalton et al’s study on nursing students in rural Tasmania found that interactions with the rural community extended beyond their professional role, integrating into their personal identities and interactions within the community73. Participants emphasised the need to ‘develop a rural nurse identity’. Community interaction was also highlighted among undergraduate nutritionist and dietetic students in Newcastle65, and various undergraduate students in Sydney66. These interactions illustrate that the intimate nature of rural communities allows for deeper connections between healthcare professionals and community members, enabling students to experience the community’s lifestyle and values first-hand.

Social isolation

Three articles identified social isolation as an experience that inhibits a sense of belonging among healthcare students during rural placements16,60,66. Students faced challenges related to financial stress, accommodation, travel, and the lack of familiar social and recreational activities16,60,66. These studies highlighted the impact of being separated from family and friends, which decreased the sense of belonging to the rural and remote environment. Bradley et al identified social isolation as a critical factor negatively impacting student placement experiences and satisfaction60. However, Smith et al indicated that if students perceived they could overcome social isolation, they found the rural placement rewarding, with a sense of belonging contributing to their personal development16.

Community activity engagement

Community activity engagement involves healthcare students participating in various community events and activities during their rural placements. Such engagement was highly valued and enhanced their sense of belonging. A significant number of studies (n=10) indicated that community activity engagement significantly contributed to a student’s sense of belonging16,37,61,63-65,67,68,70. These activities helped students feel more integrated and valued as part of the community. While some publications broadly labelled these activities as ‘community activities’69,70,74, others provided clear examples. Sporting activities, such as joining local netball and table tennis teams, were prominent37,63,66. Other activities included bushwalking, community jogging and gym memberships16,63,67. Walker et al described how participating in local events and activities allowed students to build relationships with community members, understand local cultures and feel more connected to their work environment67. Fisher et al64 and Sutton et al37 outlined how community engagement bridges the gap between clinical work and community life, outlining perspectives on rural health issues and social determinants of health. By actively participating in community events, students could see first-hand the impact of health care on community members’ lives outside the clinical setting. Elliott et al noted that, despite these opportunities, students were sometimes dissatisfied with the lack of extracurricular engagement opportunities offered in the rural and remote locality compared to their home environment68.

Discussion

Thirteen studies explored the events and experiences that influenced medical, nursing and allied health students’ sense of belonging in rural and remote communities during clinical placements. The findings highlighted three themes: rural environment and the formation of a rural identity, social isolation and community activity engagement. Understanding the possible events and experiences can help educational institutions and industry partners design and benchmark placements that positively impact students’ desire to return to rural and remote environments post-graduation.

The social aspects of rural placements for healthcare students are often overlooked, leading to significant challenges in student retention and satisfaction. Traditional emphasis on clinical training and professional development often overshadows the equally important social integration into rural communities. Social integration plays a crucial role in mitigating the risk of isolation for students separated from their usual social networks16. Previous literature underscores the significance of rural placement models that actively integrate students into rural communities to enhance their engagement and sense of belonging34,39. For students without prior rural experience, building social connections within the community is crucial13,34,75. Immersion in rural culture has been identified as a significant factor in encouraging individuals to stay in rural and remote areas76.

Trede et al77, Green et al39 and Levett-Jones et al41 highlight that rural identity and a sense of belonging are closely intertwined, influenced by dynamic, relational and contextual factors. A strong sense of belonging can increase the likelihood of undergraduate students considering returning to rural areas after graduation. Opportunities to meet people and develop social networks in the rural community are fundamental for retention34. Engaging with rural communities, beyond clinical exposure, helps students develop a broader rural identity and understand their role in addressing the health needs of diverse populations in rural settings39,41. According to Levett-Jones et al, students need to be accepted as community members by both clinical and community teams41. Sedgwick and Yonge found that the quality of interpersonal interactions influences students’ sense of belonging, emphasising the need for acceptance beyond the clinical environment13. Healthcare policies and educational programs have predominantly focused on enhancing clinical skills and providing financial incentives to attract and retain students in rural areas. However, the holistic experience of living in these communities, which includes social engagement and forming personal connections, is critical for developing a sustainable rural workforce. Further research is needed to explore the nuanced meanings of belonging and rural identity in the context of student placements in rural health.

This scoping review identified the impact of social isolation on undergraduate students’ ability to develop a sense of belonging in the rural and remote community. Research articles highlighted that feelings of being welcomed, valued and supported by local community members during clinical placement influenced the feeling of belonging. Studies by Bradley et al60, McAllister et al66 and Smith et al16 examined the concern that rural placements in isolation can adversely affect students’ sense of connection, leading to loneliness and decreased overall satisfaction. To address these challenges, strategies such as sending multiple students to the same rural and remote facility or accommodating students in shared housing have been implemented40. This concept, known as ‘ruralisation’, involves positive interactions within a friendly and supportive community16,78. When students from various health disciplines share accommodation, it fosters valuable social network and enhances interprofessional collaboration and teamwork79. Transportation issues can also exacerbate feelings of isolation, limiting students’ ability to engage with the community and participate in social activities80,81. Further research is needed to identify additional strategies to decrease social isolation and its impact on students’ sense of belonging during rural placements.

The study results emphasised that participating in community activities among undergraduate students created opportunities for fostering a sense of belonging. Missing familiar social and recreational activities disconnects students from their usual support systems, leading to feelings of loneliness, and decreased overall satisfaction and wellbeing during placement. Further exploration is needed to identify which ‘community activities’ influence this feeling. Current descriptions of these activities are superficial, and more research is required to understand their relationship with students’ sense of belonging. Prior research indicates that integrating with the local community helps students gain a deeper understanding of rural practice64. Encouraging students to engage in community activities and local events mitigates feelings of isolation, fosters a sense of belonging and aids integration into a rural lifestyle61,69. While sports are vital for fostering social connections and a sense of community, other interests should be explored to cater to diverse student needs. Activities such as local volunteer work, participation in community projects and joining hobby groups provide alterative avenues for social engagement82,83. Creating opportunities for students to immerse themselves in various community activities helps them form meaningful relationships and a stronger sense of belonging. Students’ professional and personal lives often overlap, reinforcing their commitment to rural settings and influencing their career choices toward rural practice. Further research is needed to identify the impact of participation in community events and activities on students’ social integration and a sense of belonging during rural placements.

Despite these efforts, there is a notable lack of research exploring the relationship between community involvement, social activities, and healthcare students’ employment intentions in rural and remote areas. Most studies have focused on clinical placement experiences and the supervisor–supervisee relationship within the workplace, neglecting the broader community socialisation context. This gap in our understanding highlights the need for comprehensive research to explore the factors that influence students’ sense of belonging in rural and remote communities. Further investigation is needed to explore how community events, social interactions and extracurricular activities impact a student’s overall placement experience and career intentions. Understanding these dynamics can inform the development of more holistic rural placement programs that address both clinical and social aspects, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable rural healthcare workforce.

Limitations

The review focused on peer-reviewed evidence, deliberately excluding grey literature, which may have limited the contextual richness of the findings. The overall quality of evidence was considered low, primarily due to small sample sizes and various biases, such as researcher bias, selection bias and information bias. These biases impacted the validity and reliability of the studies, highlighting the need for improved methodologies in future research. The review did not identify international literature, possibly due to search strategy biases and the criterion of including only English-language studies, which may have excluded relevant non-English studies and affected the global applicability of the recommendations. Excluding grey literature aimed to ensure the reliability and quality of the synthesised evidence but may have omitted relevant studies. The low quality of the studies was noted, with contributing factors including small sample sizes, biases and methodological flaws. Addressing these issues in future research is crucial to enhance the robustness and applicability of the findings.

Conclusion

It is evident that multiple events and experiences influence undergraduate healthcare students’ sense of belonging in rural and remote placements. The themes identified – rural environment and identity formation, social isolation and community engagement – highlight the complexity of this phenomenon. Positive experiences in the clinical workplace and supportive learning are crucial for fostering a sense of belonging among students; however, social integration into rural and remote communities is equally vital. The literature highlighted that a welcoming community positively affects students’ sense of belonging and can mitigate social isolation. The formation of a rural identity and the welcoming nature of the community also play significant roles. Conversely, social isolation can hinder students’ sense of belonging. Community engagement through various activities emerged as a key event/experience in enhancing students’ connections to rural and remote areas. Moreover, there are identified gaps in the existing literature, particularly in understanding the nuanced relationships between community involvement and social activities of healthcare students in rural areas. There is a need for future research to undertake a deeper exploration of the dynamics of belongingness to inform comprehensive placement programs that address both clinical training and social integration needs effectively. By addressing these factors, healthcare students’ sense of belonging during rural placements can be significantly enhanced, ultimately leading to better retention and satisfaction with rural practice.

References

appendix I:

Appendix I: Keyword combinations

| Key concept 1 | Key concept 2 | Key concept 3 | Key concept 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Health personnel "Students, Health Occupations" "Allied Health Personnel" OR "Dentists" OR "Nurses" OR "Nutritionists" OR "Occupational Therapists" OR "Pharmacists" OR "Physical Therapists" OR "Physicians" OR Nurs* OR Physician* OR Doctor* OR Dentist OR "Allied health" OR Physiotherap* OR "occupational therap*" OR "speech therap*" OR "speech pathologist*" OR Dental* OR Paramed* OR Ambulance* OR Psychologist* OR Dietetic* OR Dietitian* OR Dietician* OR Nutritionist* OR "social worker*" OR "Aboriginal health practitioner*" OR Pharmac* |

Preceptorship Placement* OR WIL OR "work integrated learning" |

Rural health service Rural OR Remote OR "modified Monash" OR Region* |

Social environment Social* OR Communit* OR Connect* OR Belong* OR Cultural* OR Engage* OR Involve* OR Support* OR Lifestyle OR Experience* OR Immersion |

Appendix II: Exemplar of search strategy used in PubMed

((MESH.EXACT("Health Personnel") OR MESH.EXACT("Allied Health Personnel") OR MESH.EXACT(Dentist) OR MESH.EXACT(Nurse) OR MESH.EXACT(Nutritionist) OR MESH.EXACT("Occupational therapist") OR MESH.EXACT(Pharmacist) OR MESH.EXACT("Physical Therapist") OR MESH.EXACT(Physician)) OR (TI,AB,IF(Nurs*) OR TI,AB,IF(Physician*) OR TI,AB,IF(Doctor*) OR TI,AB,IF(Dentist*) OR TI,AB,IF("Allied health") OR TI,AB,IF(Physiotherap*) OR TI,AB,IF("occupational therap*") OR TI,AB,IF("speech therap*") OR TI,AB,IF("speech pathologist*") OR TI,AB,IF(Dental*) OR TI,AB,IF(Paramed*) OR TI,AB,IF(Ambulance*) OR TI,AB,IF(Psychologist*) OR TI,AB,IF(Dietetic*) OR TI,AB,IF(Dietitian*) OR TI,AB,IF(Dietician*) OR TI,AB,IF(Nutritionist*) OR TI,AB,IF("social worker*") OR TI,AB,IF(Pharmac*))) AND ((MESH.EXACT(Preceptorship) OR MESH.EXACT("Students, Health Occupations")) OR (TI,AB,IF(Placement*) OR TI,AB,IF(WIL) OR TI,AB,IF("work integrated learning")))) AND ((MESH.EXACT("Rural Health") OR MESH.EXACT("Rural Health Services")) OR TI,AB,IF(Rural) OR TI,AB,IF(Remote) OR TI,AB,IF("modified Monash") OR TI,AB,IF(Region*)))) AND ((MESH.EXACT("Social Environment")) OR (TI,AB,IF(Social*) OR TI,AB,IF(Communit*) OR TI,AB,IF(Connect*) OR TI,AB,IF(Belong*) OR TI,AB,IF(Cultur*) OR TI,AB,IF(Engage*) OR TI,AB,IF(Involve*) OR TI,AB,IF(Support*) OR TI,AB,IF(Lifestyle) OR TI,AB,IF(Experience*) OR TI,AB,IF(attach*) OR TI,AB,IF(identity) OR TI,AB,IF(immersion) OR TI,AB,IF("rural immersion"))