Introduction

There are major health disparities between people living in rural and remote areas and those living in metropolitan areas1. Rural and remote areas are typically classified as areas outside of major cities that face unique challenges accessing health care1. In Australia, people living in rural and remote areas experience higher rates of death, injuries, disease and hospitalisation2. Support for health and wellbeing can be provided by allied health professionals (AHPs). AHPs are tertiary qualified practitioners providing support for health and wellbeing for individuals or communities, separate to nursing, medicine and dentistry professionals3. Complex challenges in recruitment, retention and turnover of AHPs exist globally and negatively impact upon the provision of rural and remote services1. Workforce challenges result in reduced access for rural and remote populations to allied healthcare services despite a growing demand for these services2,4. Strategies to increase access to allied health in rural and remote settings include telehealth; however, despite this mode of delivery expanding during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is not being provided routinely, with community-based services continuing to be the preferred option5-7. A fully staffed and skilled allied health workforce is imperative to manage and improve the poorer health experienced by the rural and remote population1,8.

WHO has produced guidelines to support national authorities to address rural and remote health workforce challenges1. These guidelines recommend personal and professional support interventions including supporting students with rural backgrounds, providing education and professional development in rural areas, and improving career advancement opportunities, safe working environments and living conditions for health workers1. Although a lack of evidence exists on the implementation and success of these interventions to date, Australia has several targeted initiatives that align with these recommendations. Until recently such initiatives have predominantly focused on medicine and included funded university places for students from rural backgrounds, financial incentives and support to encourage doctors to work in rural or remote areas on graduation9,10.

Research has explored factors, including those outlined in the WHO guidelines relating to recruitment, retention and turnover of the healthcare workforce in rural and remote areas. Several reviews have explored health professional retention factors, but findings and recommendations have largely been drawn from studies examining the medical profession11-13. To date, findings relating to the allied health workforce have been isolated and have not been synthesised collectively. A recent qualitative review exploring the experience of remote and rural AHPs identified a range of professional and organisational factors associated with workforce challenges and opportunities such as supervision, human resources, workplace culture, autonomy and access to professional development14. However, the review only included qualitative studies and did not include studies measuring turnover or associated costs. A further review focused on recruitment and retention, demographics and trends and person factors affecting the recruitment and retention of rural AHPs. However, the review largely focused on qualitative studies and did not focus on studies reporting length of employment or studies measuring turnover and associated costs15. Recently, a scoping review on attrition rates across allied health disciplines found that organisational and professional themes both contributed to attrition; however, the review was not rural- and remote-specific16. Thus, there is a gap in the literature in relation to quantitative data on rural AHP recruitment and retention.

High recruitment, relocation and training costs such as temporary staffing and overtime, advertising, interviewing and relocation, orientation and training are incurred for employers who experience a high turnover of staff4. Research exploring the costs associated with turnover and retention within the allied health workforce is scarce. In 2011, a study calculated direct and indirect costs associated with recruiting AHPs, but since then there has been limited research in this area to expand upon the findings4. With more knowledge about rural and remote allied health retention and turnover, researchers, policymakers and organisations will be more informed about the patterns, determinants and costs that impact workforce initiative outcomes.

This scoping review was undertaken to explore gaps in evidence by examining the length of employment of AHPs, and significant factors and costs associated with the recruitment, retention and turnover of the rural and remote allied health workforce.

The questions posed by this review were:

- What is the length of employment for AHPs working in rural and remote areas?

- What are the associated costs of rural and remote AHP turnover?

- What factors are associated with AHPs recruitment, retention and turnover in rural and remote areas?

Methods

The scoping review followed the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews17 to identify the literature describing the length of employment of AHPs in rural and remote areas, factors associated with recruitment, retention and turnover and associated costs. A scoping review was chosen because this review is, to our knowledge, the first quantitative exploration of this emerging field, and such a review can identify the gaps in the literature relating to the research aim and provide an overview of the evidence available.

Search strategy

Articles from six databases (MEDLINE, Cinahl, Web of Science core collection, Scopus, Proquest Dissertations & Theses Global and Proquest) were screened (December 2023) by title and abstract. These databases were chosen to provide a comprehensive coverage of the literature by including both subject-specific and multidisciplinary databases. Grey literature was also searched using Worldwide Science.org and Google Scholar (Australia) by screening the first 200 hits to include sources beyond traditional academic publications. Key search terms related to AHPs, rural and remote environments, recruitment, retention and turnover. Table 1 outlines the MEDLINE search terms which were adapted for each database to align with the individual database style and phrasing requirements.

Table 1: MEDLINE search for literature describing length of employment of allied health professionals in rural and remote areas, factors associated with recruitment, retention and turnover and associated costs

| Search | Query | Records retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | allied health personnel/ or audiologists/ or dental staff/ or dentists/ or nutritionists/ or occupational therapists/ or optometrists/ or pharmacists/ or psychotherapists/ or Dental Hygienists/ or Osteopathic Physicians/ | 65,469 |

| 2 | Social Workers/ or Genetic Counseling/ or Physical therapists/ | 20,046 |

| 3 | ("allied health" or "art therapist*" or audiologist* or chiropractor* or dietician* or dietitian* or "exercise physiologist*" or "genetic counsellor*" or "music therapist*" or nutritionist* or "occupational therapist*" or "optometrist* or oral health therapist*" or "dental therapist" or orthoptist* or orthotist* or prosthetist* or perfusionist* or pharmacist* or physiotherapist* or "physical therapist*" or osteopath* or podiatrist* or psychologist* or "rehabilitation counsellor*" or "rehabilitation counselor*" or radiographer* or sonographer* or "radiation therapist*" or "social worker*" or "speech pathologist*" or "speech language pathologist*" or "speech language therapist*" or "speech therapist*" or logopedia*).tw,kf. | 145,583 |

| 4 | ((health or healthcare or "health care") adj2 (personnel or worker* or staff or professional* or provider*)).tw,kf. | 311,181 |

| 5 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 | 491,622 |

| 6 | Rural Population/ | 69,732 |

| 7 | ((rural or remote or nonmetropolitan) adj2 (communit* or area* or region* or province* or personnel or population)).tw,kf. | 92,637 |

| 8 | ((rural or remote or nonmetropolitan) adj2 (health service* or "health care" or healthcare or hospital or hospitals or service* or school or schools or setting or clinic* or workplace)).tw,kf. | 24,156 |

| 9 | 6 or 7 or 8 | 147,019 |

| 10 | Personnel Turnover/ | 5988 |

| 11 | "Personnel Staffing and Scheduling"/ | 18,088 |

| 12 | Personnel Selection/ | 13,624 |

| 13 | Health Workforce/ | 14,557 |

| 14 | (Turnover or "Turn over" or recruit* or retention or workforce or retain* or Shortage* or Tenure).tw,kf. | 1,116,961 |

| 15 | 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 | 1,152,425 |

| 16 | 5 and 9 and 15 | 2968 |

| 17 | meta-analysis/ or "systematic review"/ | 330,904 |

| 18 | (quantitative or statistic* or correlation).tw,kf. | 3,047,679 |

| 19 | review.pt. | 3,247,535 |

| 20 | ("systematic review*" or "meta-analysis" or metaanalysis or "Retrospective Design" or "evaluation research").mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | 492,833 |

| 21 | ((prospective or retrospective or "non- experimental") adj (Study or studies)).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | 1,935,137 |

| 22 | 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 | 7,883,642 |

| 23 | 16 and 22 | 771 |

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies included AHP participants working in rural or remote settings. For this review AHPs were defined based upon the accepted ‘AHPs Australia’ criteria and included arts therapy, audiology, practising nutritionists, chiropractics, counselling and physiotherapy, diabetes educators, dietetics, exercise physiology, genetic counselling, medical radiation, music therapy, occupational therapy, orthoptics, orthotics/prosthetics, osteopathy, paramedic practitioners, pedorthist custom makers, perfusion, pharmacy, physiotherapy, podiatry, psychology, rehabilitation counselling, social work, sonography and speech pathology3. A study was defined as being rural or remote if the authors of the study had classified the study as a rural or remote study. This approach was taken because as far as we are aware there is no global definition of rural and remote health, and what areas are considered to be rural and remote will vary between countries, and sometimes even within regions of those countries. The review included studies using a quantitative approach, or a mixed-methods approach with a quantitative component. Included studies had to report on at least one of the following: recruitment, retention, turnover, length of employment or associated costs of AHPs in rural or remote settings. The review considered studies in all settings such as hospital, community health care, private practice or non-government organisations based in any country. Studies were excluded if they were not reported in English. Systematic reviews were also excluded.

Procedure

Citations were extracted from the electronic databases into the web-based software Covidence platform (Veritas Health Innovation; http://www.covidence.org) and duplicates removed. The first stage of screening involved two reviewers (AD, DK) independently screening the articles by title and abstract. Any articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The second stage of screening involved three reviewers (AD, DK, RM) screening the full texts of the articles that met the inclusion criteria, with each text being screened by two of the reviewers. Conflicts were resolved via a discussion between the reviewers and a further independent reviewer (CB).

Data analysis

Data (author, year of publication, location, purpose, methodology, sample size, age range, gender, type of AHP, population type (rural or remote, or mix of rural, remote, metro), costs and cost components, employment duration (length of employment), factors affecting recruitment, retention or turnover) were extracted into Microsoft Excel by DK and GT. Further data on factors affecting recruitment, retention and turnover were extracted from each study into Excel and were examined to identify if the factors were tested for significance (DK), and then reviewed (JC). Where multiple models were used in one study to test for significance, the findings of the final or fully adjusted model for extraction were utilised. Factors were then grouped into categories; age, gender, family preferences, having an Australian background, experiencing a rural background, undertaking a rural placement, integration into the community (personal), opportunities for career development, duration of employment, workplace setting, working conditions and financial incentives (organisational).

Ethics approval

This study is a scoping review of previously published literature and did not engage any human participants or collect and primary data. Therefore, no ethics approval was required.

Results

Study inclusion and characteristics of included studies

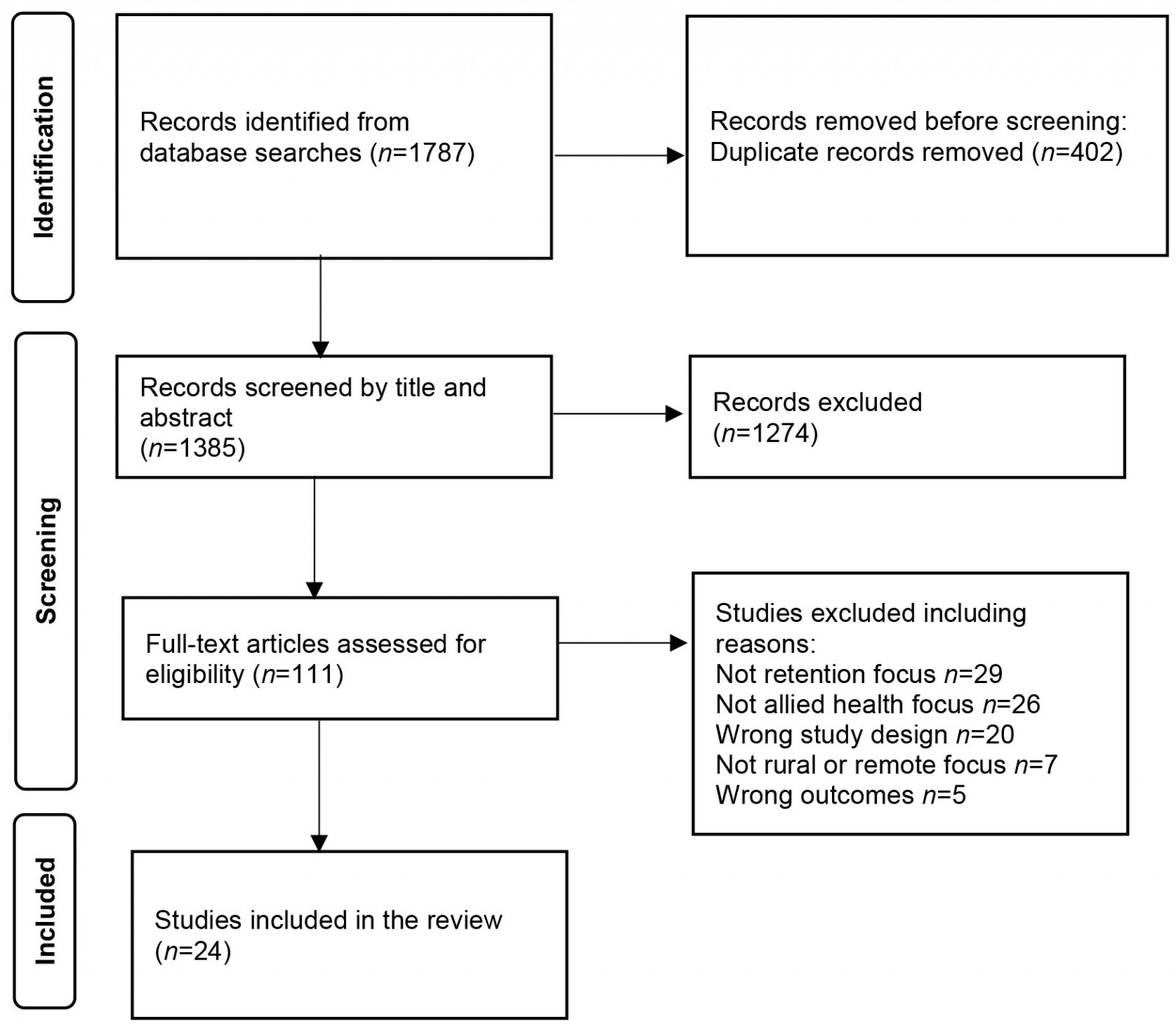

As detailed in Figure 1, the search retrieved 1787 studies. After removing 402 duplicates, 1385 studies were screened by title and abstract with 1274 studies excluded. A total of 111 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility with 87 studies excluded. A total of 24 studies were included in the review.

Studies were published between 1991 and 2023. Nineteen studies used solely quantitative methodology with five studies adopting a mixed-methods approach. Sample sizes ranged from five to 1879 AHPs. Studies were conducted in Australia (15), Canada (5), the US (1), South Africa (1), Europe (1) and Scotland (1). Thirteen studies focused on a range of AHPs and three studies focused on pharmacists, three on physiotherapists, two on occupational therapists, and one each on dietitians, rehabilitation counsellors and speech pathologists. Detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of search results, study selection and inclusion.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of search results, study selection and inclusion.

Table 2: Characteristics of selected studies

| Author(s), year | Location | Purpose | Sample characteristics | Allied health profession | Population | Study design | Length of service | Costs included | Factor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chisholm et al (2011)4 | Australia | Patterns and determinants of turnover and retention, costs of recruitment |

n=901 14.2% male |

Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | Yes | Turnover |

| Keane et al (2011)18 | Australia | Demographics, employment and education factors affecting recruitment and retention |

n=1879 31% male |

Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | No | Recruitment Turnover |

| Solowiej et al (2010)19 | Scotland | Evaluation of a scheme to recruit and retain allied health professionals | – | Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | No | No |

| Humphreys et al (2009)20 | Australia | To develop and validate a workforce retention framework for small rural and remote primary healthcare services | – | Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | Yes | No |

| Haskins et al (2017)21 | South Africa | Factors influencing recruitment and retention |

n=25 18–55 years 32% male |

Allied health | Rural or remote, and metro | Quantitative | Yes | No | No |

| Brown et al (2010)22 | Australia | Recruitment and retention issues for the rural dietetic workforce |

n=31 90.3% male |

Dietetics | Rural or remote, and metro | Mixed methods | Yes | No | No |

| Wielandt and Taylor (2010)23 | Canada | Rewards and challenges of current practice |

n=59 22–71 years 41% male |

Occupational therapy | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | No | Turnover |

| Woodend et al (2004)24 | Canada | To develop a tool to assist in recruitment and retention in rural and remote communities |

n=1019 30–65 years 55.3% |

Pharmacy | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | No | Retention |

| Devine et al (2013)25 | Australia | Impact of the Queensland Health Rural Scholarship Scheme on workforce outcomes |

n=146 19–65 years 18.5% male |

Allied health | Rural or remote | Mixed methods | Yes | No | No |

| Brown et al (2017)26 | Australia | Short-term workforce outcomes of a rural student placement |

n=129 (baseline), 24 (follow-up) 90.3% male |

Allied health | Metro mix | Mixed methods | Yes | No | Recruitment Turnover |

| Winn et al (2015)27 | Canada | Recruitment of graduates to rural and remote areas |

n=282 20–49 years 15% male |

Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | No | No | Recruitment Retention Turnover |

| Fleming and Spark (2011)28 | Australia | Factors influencing the choice of practice location |

n=84 23–64 years 29.8% male |

Pharmacy | Rural or remote, and metro | Quantitative | No | No | Recruitment |

| Gittoes et al (2011)29 | Australia | Influences on recruitment and retention |

n=19 25–65 years 23.6% male |

Rehabilitation counselling | Rural or remote–metro mix | Mixed methods | No | No | Recruitment Retention |

| Whitford et al (2012)30 | Australia | Demographics, employment, education, and factors affecting recruitment and retention |

n=1539 51–75 years 18% male |

Allied health | Rural or remote, and metro | Quantitative | No | No | Retention Turnover |

| Carson et al (2015)31 | Europe | The rural pipeline and retention | n=248 | Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | No | No | Retention |

| Gallego et al (2015)32 | Australia | Importance of job characteristics and their effect on retention |

n=165 23–68 years 6% male |

Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | No | Retention |

| Terry et al (2023)33 | Australia | To assess the usability and capacity of a pilot questionnaire to measure rural recruitment and retention | n=19 | Pharmacy | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | No | Recruitment Retention |

| Keane et al (2013)34 | Australia | Sector differences in factors affecting retention |

n=1589 20–60 years 31.5% male |

Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | Yes | No | Turnover |

| Beggs and Noh (1991)35 | Canada | Personal, organisational and environmental factors that influence retention |

n=196 26–55 years 18.3% male |

Physiotherapy | Rural or remote | Quantitative | No | No | Turnover |

| Berg-Poppe et al (2021)36 | US | Values of physiotherapists that accept and maintain employment |

n=373 23–75 years 24.4% male |

Physiotherapy | Rural or remote, and metro | Quantitative | No | No | Recruitment Turnover |

| Denham and Shaddock (2004)37 | Australia | Recruitment and retention of allied health professionals | n=31 | Allied health | Rural or remote | Quantitative | No | No | Recruitment Retention |

| Foster and Harvey (1996)38 | Canada | Reasons for leaving rural employment |

n=87 26–46 years 9.2% male |

Speech pathology | Rural or remote | Quantitative | No | No | Retention |

| McMaster et al (2021)39 | Australia | Evaluation of the Allied Health Rural Generalist Pathway |

n=5 20–30 years 40% male |

Physiotherapy | Rural or remote | Mixed methods | Yes | No | Recruitment Retention |

| Merritt et al (2013)40 | Australia | The nature of private practice in rural and remote areas and whether such practice is viable |

n=37 18–55 years 37% male |

Occupational therapy | Rural or remote | Quantitative | No | No | Turnover |

Length of employment

Recruitment and retention of AHPs in remote and rural areas were measured inconsistently using a variety of different methods such as average length of employment (n=7), median length of employment (n=4), maximum and minimum length of employment (n=4), median survival (n=1) and survival probabilities (n=2) (Table 3). Typically, length of employment was short, with a decline after 1 year of employment.

An Australian study investigating the demographics, employment, education and factors affecting recruitment and retention of AHPs working in more than 21 different roles in regional, rural and remote areas in New South Wales reported the longest average duration out of all the studies (11.4 years)18. Solowiej et al’s study investigating the impact of a scheme to support the recruitment, retention and career development of AHPs (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, dieticians and radiotherapists) in rural Scotland identified the shortest average length of employment of 1.5 years19.

The longest median length of employment for AHPs was 3.2 years in a study examining health workforce benchmarks and recruitment costs for primary health care services in rural and remote areas across Australia20. A South African cross-sectional study investigating factors associated with the recruitment and retention of nurses, doctors and AHPs in rural hospitals highlighted the shortest median length of employment of 1 year for AHPs21. A mixed-methods study determining the recruitment and retention issues for dietetic services in rural New South Wales reported a minimum duration in post of 2 months with a maximum duration of 26 years22. Wielandt and Taylor’s study seeking to identify the rewards and challenges for female occupational therapists working in rural communities in Western Canada reported a similar duration (0.8 years to 25 years)23.

In an employment context, ‘survival’ refers to the probability of an employee remaining in their employment for a specific period41. Survival analysis identified a median survival of 3 years for rural AHPs and 2 years for remote AHPs in Australia, with a survival probability of 0.74 at 1 year and 0.52 at 2 years20. Similarly, Chisholm et al (2011) reported similar survival probabilities of 0.75 at 12 months and 0.57 at 2 years for Australian AHPs4.

Woodend et al’s study investigating the retention of pharmacists in rural Canada found most pharmacists intending to stay in their role had practised between 6 and 15 years (37%) while most pharmacists intending to leave had been working less than 5 years (37%)24. A study exploring the recruitment outcomes and retention of the Queensland Health Rural Scholarship Scheme for AHPs found 13.7% of the AHPs had not completed the 2-year term of employment following graduation that was required of the scholarship scheme25. Due to the variety of methods used to measure length of employment, the data was difficult to synthesise; however, the important overall finding indicates that length of employment is short when compared to that of urban AHPs42, with subsequent cost implications for employers.

Table 3: Reported length of employment for allied health professionals

| Author(s), year |

Region |

Profession | Average length of employment (years) | Median length of employment (years) | Range of stay (years) | Median survival (years) | Survival probability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 2 years | |||||||

| Chisholm (2011)4 |

Australia |

Allied health | 3.1 | 0.75 | 0.57 | |||

| Keane et al (2011)18 |

Australia |

Allied health | 11.4 | |||||

| Solowiej et al (2010)19 |

Scotland |

Allied health | 1.5 | |||||

| Humphreys et al (2009)20 |

Australia |

Allied health | 3.2 | 3 (rural) 2 (remote) | 0.74 | 0.52 | ||

| Haskins et al (2017)21 |

South Africa |

Allied health | 1 | |||||

| Brown et al (2010)22 |

Australia |

Dietetics | 4.5 | 0.17–26 | ||||

| Wielandt and Taylor (2010)23 |

Canada |

Occupational therapy | 3.9 | 0.8–25 | ||||

| Woodend et al (2004)24 |

Canada |

Pharmacy | 15 | 5–25 | ||||

| Brown et al (2017)26 |

Australia |

Allied health | 1† | |||||

| Gallego et al (2015)32 |

Australia |

Allied health | 5.2 | |||||

| McMaster et al (2021)39 |

Australia |

Allied health | 2.9 | 0.25–3.83 | ||||

† Median approximately 1 as 52% AHPs were retained 1 year post-graduation, 37.5% for 3 years post-graduation.

Costs

Only two identified studies estimated the costs of workforce turnover for AHPs, and both were conducted over 10 years ago. Humphreys et al focused on direct costs associated with workforce turnover in rural and remote settings. They identified the overall direct replacement cost as A$21,925 per new recruitment, with vacancy and recruitment costs the largest component of this (A$7000, A$6500) and orientation costs the lowest (A$4000)20.

In a subsequent study, Chisholm et al (2011) estimated the median costs associated with workforce turnover in rural and remote Victorian health services, including dietitians, occupational therapists, podiatrists, psychologists, social workers, speech pathologists and physiotherapists4. This study calculated not only median direct costs (A$18,882), but also median indirect costs (A$1200) associated with recruiting to rural and remote health services. Direct costs comprised the largest proportion of overall costs and included vacancy-related costs such as temporary staff, overtime, expenses due to patient transfers and loss of contractual work. These costs varied greatly based on the location of the health service (A$42,049 for remote health services compared to A$3130 for rural health services). Recruitment costs (advertising, recruitment agency, interviewing and relocation) were calculated as A$2150 for regional health services, A$3800 for rural health services and A$3888 for remote health services. Generally, indirect costs such as the cost of decreased productivity among remaining staff members and cost of initial reduced productivity of new recruits were significantly lower than direct costs. However, indirect costs were particularly high for regional health services (A$12,500) compared to rural (A$5300) and remote (A$540) health services4. Overall, both studies indicate a relatively high cost for workforce turnover in comparison to the average salary of an allied health professional, but there remains a significant gap in the literature as changes in costs are likely to have occurred since these studies.

Factors

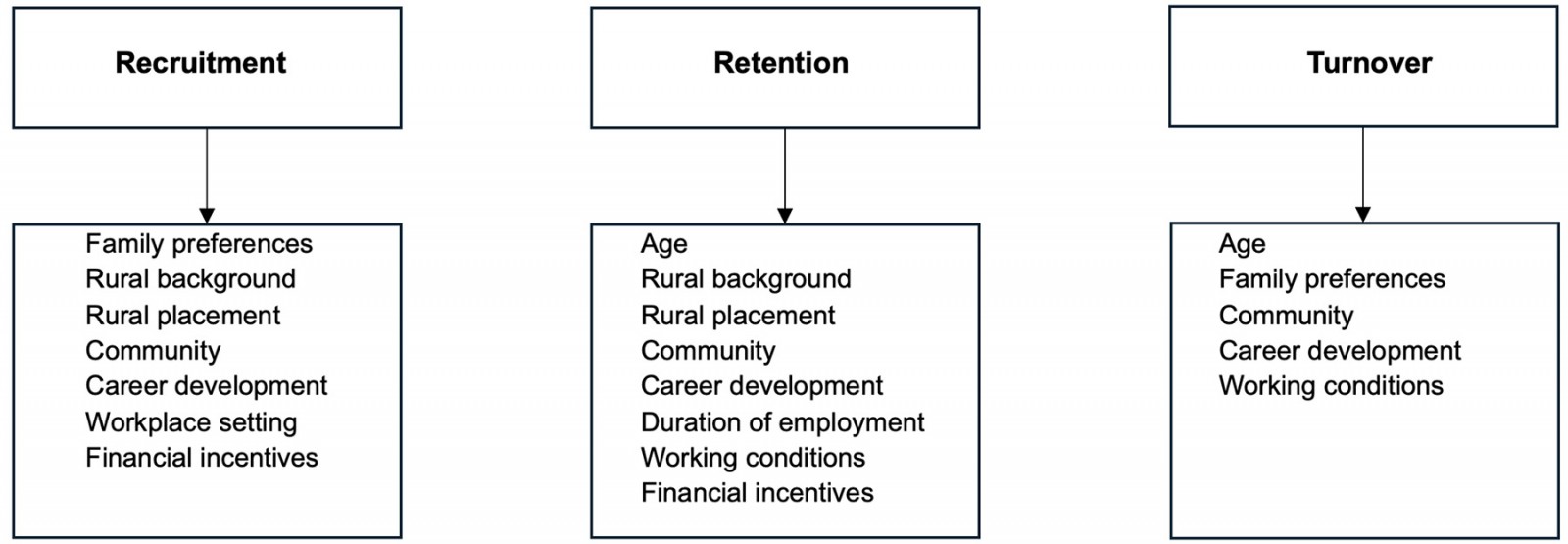

A variety of personal and organisational factors impacted upon the recruitment, retention and turnover of AHPs in rural and remote areas (Table 4, Fig2).

Table 4: Factors tested for significance in influencing allied health professional recruitment, retention and turnover in rural and remote areas

| Theme and author(s), year | Personal factors | Organisational factors | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (older age) | Gender (male) | Family preferences† | Having an Australian background | Experiencing a rural background | Undertaking a rural placement | Integration into the community | Opportunities for career development | Long duration of employment | Workplace setting | Good working conditions | Good financial incentives | |||||

| Recruitment | ||||||||||||||||

| Brown et al (2017)22 | NS | ↑ | ↑ | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||||||

| Winn et al (2015)27 | ↑ | ↑ | NS | |||||||||||||

| Fleming and Spark (2011)28 | NS | NS | NS | ↑¶ | ↑ | ↑ | ||||||||||

| Gittoes et al (2011)29 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ||||||||||||

| Retention | ||||||||||||||||

| Woodend et al (2004)24 | ↑ | NS | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||||||||

| Winn et al (2015)27 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||||||||||||

| Whitford et al (2012)30 | ↑ | ↑ | ||||||||||||||

| Carson et al (2015)31 | NS | NS | ||||||||||||||

| Gallego et al (2015)32 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||||||||||||

| Turnover | ||||||||||||||||

| Chisholm et al (2011)4 | ↓ | NS | NS | ↓‡ | ||||||||||||

| Brown et al (2017)26 | NS | NS | ||||||||||||||

| Whitford et al (2012)30 | ↓ | |||||||||||||||

| Keane et al (2013)34 | ↑ | ↓†† | NS | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||||||||||

| Beggs and Noh (1991)35 | NS | NS | ↓ | NS | ↓ | NS | ||||||||||

| Berg-Poppe et al (2021)36 | NS | ↓§ | NS | NS | NS | |||||||||||

† Being family orientated, close family proximity, spouse satisfied with rural lifestyle, being married, having children.

¶ Having a spouse or partner from a rural background was significant. Having a rural childhood was not significant.

§ Community assets was significant. Attachment to the community was not significant.

‡ Being employed on a higher grade was significant. Being employed part-time or full-time was not significant.

†† Both older age and younger age were significant.

↑, positive association. ↓, negative association. NS, tested for significance but was not significant.

Figure 2: Significant factors associated with allied health professional recruitment, retention and turnover in rural and remote areas.

Figure 2: Significant factors associated with allied health professional recruitment, retention and turnover in rural and remote areas.

Recruitment

Rural background

There were mixed findings on whether a rural background was significantly associated with working in a rural or remote area. One study analysing the short-term workforce outcomes of a student placement program in rural Australia reported newly graduated AHPs with a rural or remote background were 2.35 times more likely to be employed in a rural or remote setting than AHPs with a metropolitan background26. Winn et al (2015) also found that a rural background was significantly associated with AHPs’ decisions to practise in a rural or remote area after graduation27. Similarly, pharmacists having a spouse or partner with a rural background was also found to be significantly associated with employment in a rural area28. Interestingly, one study found that a rural childhood showed a positive association but was not found to be a significant factor for pharmacists employed in rural areas28.

Family preferences and the community

Other personal factors such as being family orientated and enjoying the rural lifestyle were reported to influence the rural recruitment of rehabilitation counsellors29. However, personal factors such as having a spouse/partner, thinking a rural or remote community was a good place to raise children, family proximity, family attachments, past rural employment, having Australian-born parents and the preference to live in small communities did not significantly influence rural employment for AHPs26-28.

Rural placements

Three studies reported a significant relationship between rural placements and employment in rural areas26-28. Brown et al’s study found graduates from a metropolitan background who had undertaken a rural placement were more likely to work in a rural or remote setting post-graduation26. A further study exploring recruitment of AHPs to rural and remote areas in Canada also found undertaking a rural or remote placement and the number of placements were positively associated with the decision to work in a rural or remote location after graduation27. Likewise, pharmacists who had undertaken rural internships were nine times more likely to be employed rurally than those who had not28.

Workplace setting

This review also identified a negative relationship between employment as a hospital pharmacist and rural employment, with pharmacists employed in hospitals significantly less likely to work in rural areas28.

Financial incentives, opportunities for career development and working conditions

Organisational factors such as receiving a supplementary income to work rurally and greater training opportunities were found to be significant factors in influencing rehabilitation counsellors' decisions to work in rural areas29. Other organisational factors such as the type of employment (permanent or temporary), acting as a sole practitioner, financial incentives, employment prospects, job satisfaction, work–life balance and being awarded a rural scholarship were tested for significance by other studies but were not found to be associated with the recruitment of AHPs to rural and remote areas26,28.

Retention

Age and duration of employment

Age and duration of employment were associated with the retention of pharmacists. Older age was significantly associated with the decision to remain working in a rural community for pharmacists in Canada24. Similarly, pharmacists who had worked more than 25 years were significantly more likely to intend to continue working in a rural area compared to those who had been practising for a shorter period24.

Family preferences

Although there was an association between being married and/or the presence of children at home with pharmacists’ intention to remain in rural employment, these relationships were not statistically significant24.

Rural background and rural placements

Two studies reported having a rural background, a rural education and choice of placement as impacting the retention of AHPs in remote and rural areas. AHPs from a rural background, and those who had attended a rural or remote university and/or had undertaken a rural placement were significantly more likely to be employed in a rural location27,30. However, Carson et al’s (2015) study investigating the retention of rural healthcare professionals found no significant relationship between AHPs with a rural background, rural education or training and retention31.

Community

In contrast, community factors such as a sense of belonging and being appreciated in the community were found to be significantly associated with the retention of pharmacists in rural Canada24.

Working conditions

Two studies identified working conditions as contributing to the retention of AHPs in rural areas24,32. Factors such as higher remuneration, less overnight work travel, professional support and autonomy of practice were found to have a significant relationship with the retention of AHPs in a rural setting24,32.

One study measured the strengths and challenges of recruiting and retaining pharmacists in rural communities. The top 10 factors were positive perception, practice autonomy, breadth of tasks, loyalty to pharmacy and pharmacists, community purpose, community recognition, financial income, practising as desired, incentives and moving allowance. The bottom 10 factors were housing interns, non-health services, schools (economic), transport connections, social/cultural opportunities, schools (geographic), community size, spousal/partner opportunities, locum/peer coverage and housing33. However, as there were no tests of significance, the reliability of the findings cannot be determined.

Turnover

Age

Age was significantly associated with the turnover of AHPs. Chisholm et al (2011) reported AHPs who were aged less than 30 years when commencing their employment were significantly more likely to leave their positions compared to those who were 35 years or older when commencing4. Similarly, a further study found younger AHPs were significantly more likely to intend to leave compared to older AHPs30. However, a study exploring factors affecting the turnover of rural AHPs identified those who were younger or older were significantly more likely to leave than those who were middle-aged34. Age was not found to be a significant factor affecting turnover for physiotherapists in rural and remote Canada35.

Family preferences

Other personal factors such as being unmarried or having a spouse dissatisfied with a rural lifestyle were also found to be significantly associated with high turnover35.

Gender

Several studies reported gender was not a significant factor associated with turnover4,34,35.

Community

Community factors were found to impact turnover. Keane et al (2013) identified AHPs working in the public sector were significantly less likely to intend to leave their employment if they felt a sense of community34. A further study investigating factors influencing employment among physiotherapists in rural America found a significant relationship between those who intended to leave their position in the next 5 years and the high value they placed on community assets such as rich cultural and entertainment venues, recreational and leisure activities, multicultural opportunities, manageable commutes to work, size of the community and realistic costs of living36. However, the same study did not find a significant relationship between attachment to the community and the intention to leave36. Beggs and Noh (1991) found no significant association between the size of community and intention to leave among physiotherapists35.

Working conditions, financial incentives and career development

Several studies identified working conditions as having an impact upon turnover. High clinical demand, lack of opportunities for career development and low-grade employment levels were all factors significantly associated with AHPs’ intentions to leave their rural employment4,34,35. However, Berg-Poppe et al’s (2021) study exploring employment acceptance among physiotherapists in rural areas found despite non-urban employees intending to leave valuing professional advancement and remuneration higher than urban employees intending to leave, this association was not significant36. Furthermore, there was no significant relationship between practice environment (eg in relation to autonomy and control, diversity of caseload, support from management) and intention to leave36. Similarly, factors influencing AHPs intending to leave their job such as a better income, better career prospects and holding a temporary contract were not found to be significant between metro and rural or remote AHPs26. Turnover risk was also not significantly related to being employed part-time or full-time4 or to length of practice35.

Discussion

This review identified the use of numerous methods to measure length of employment – such as mean, median, duration in post, annual turnover, stability and median survival – which poses difficulties in synthesising the data collectively. However, in general, length of employment was shorter in comparison to that of urban AHPs42, with a decline after 1 year of employment, which has cost implications for employers4. Only two studies reported costs, and both reported significant direct and indirect costs. It is important to consider the indirect costs, which may be more acute in rural and remote areas than metro areas due to particularities in the workforce. For example, rural or remote organisations employ smaller allied health teams, resulting in vacancies having more significant workload implications; relocation costs are higher in rural areas; and recruitment to a position is likely to be a longer process compared to that for metropolitan areas4,43.

These high costs can have a detrimental impact upon rural and remote areas, leading to a reduction in patient interactions and high service delivery costs44. The studies that included costs were over 10 years old, and substantial changes in these costs are likely to have occurred since. Therefore, it is difficult to draw conclusions from the costs identified in this review. If costs are not available, it is harder to make the case for investment in the rural and remote pipeline for targeted strategies to ensure a sustainable AHP workforce in rural and remote areas. Given this significant gap in the literature relating to costs, it is imperative that more research is undertaken in this area to fully understand costs associated with recruitment, retention and turnover of AHPs in rural and remote areas.

The articles in this review found a variety of personal and organisational factors significantly impacting upon recruitment, retention and turnover. Findings from the articles were sometimes contradictory, and this may be attributed to some studies focusing on specific AHPs and others treating AHPs as one group. However, generally, having a rural background or undertaking a rural placement had a positive impact upon recruitment and retention, and, overall, AHPs who were older were more likely to remain in employment. Being integrated into the community, opportunities for career development, good working conditions and financial incentives were also found to be significant factors positively impacting recruitment, retention and turnover. Generally, these findings concur with previous reviews that have focused on recruitment, retention and turnover of healthcare professionals in rural and remote settings33,43,45. The findings of this review indicate that policy initiatives for rural doctors, including supported university places for rural students and career and financial incentives, may also be relevant to improve allied health workforce outcomes9,10.

It is important to consider whether it is appropriate to classify AHPs as one unified comparable group or whether workforce policies should be adapted and tailored to each distinct AHP. Additionally, policies need to be considered at both jurisdictional and national levels, and there is also a need to understand how these affect private and public settings differently.

Private and non-government organisations may require government support for development of the allied health workforce equitable with available nursing and medical workforce programs. This is particularly important to meet future demand for allied health services in Australia, in line with the needs of an ageing population46 and the government's reliance on the private sector to deliver services within the National Disability Insurance Scheme47. It is imperative that policymakers use the knowledge about rural and remote allied health retention and turnover to plan and evaluate workforce initiatives to support anticipated growth.

Currently, as far as we are aware there are no global official guidelines or frameworks outlining how to measure length of employment, recruitment, retention and turnover, and this review highlighted the multiple methods and techniques adopted. As a result, it is difficult to adequately synthesise data and draw reliable conclusions in this review. Standardised methods of reporting would enable the synthesis and aggregation of data across studies to make accurate and effective recommendations. Making recommendations about which method is most appropriate to use is beyond the scope of this review. However, based on the findings of this review, a rigorous process of clarifying and defining the terms ‘length of employment’, ‘recruitment’, ‘retention’ and ‘turnover’ and a framework consisting of guidelines of appropriate tools to use when measuring these factors is recommended.

It is important to consider the strengths and limitations of this review. A major strength of this review is that previous reviews undertaken have mainly focused on medical studies and not specifically on AHPs. To our knowledge this is the first scoping review to synthesise quantitative studies on AHPs’ recruitment, retention and turnover in rural and remote areas. A further strength is that the review included searches across six databases plus grey literature. However, a scoping review summarises findings but, unlike a systematic review, does not critically appraise study quality, so findings need to be interpreted with caution.

A limitation of this review is that not all studies included in the review applied measures of significance to test associations between recruitment, retention, turnover and factors; therefore, conclusions can only be drawn from the studies that tested the factors for significant associations. However, findings of this review could be considered alongside the context of other qualitative review findings exploring AHPs’ experiences of working in rural and remote areas, and the personal and professional factors that impact upon their experience, to provide further evidence14.

Articles were included in the review and classified as rural or remote studies based upon each individual study’s definition. The definitions used to determine what constitutes a rural or remote area may impact upon the outcomes, as recruitment, retention and turnover are potentially more challenging in some rural and remote regions than others. Findings will vary due to the different economic contexts in which the research took place, and it is difficult to make generalisations across countries as each country will have its own unique structure, and policies in each country will differ. For example, local knowledge, different policies, governance, the role of the government and the interplay between local and broader structures and processes can contribute to the unique challenges experienced48. Another limitation is that the review only included studies published in English.

This review highlights the need for future research to measure the impact of allied health rural workforce incentives, interventions and strategies in place in Australia and other countries to determine recruitment, retention and turnover outcomes. Limited evidence is available about the costs associated with recruitment, retention and turnover, and therefore further research is needed to understand these costs. It is recommended that a standardised framework is developed that supports employers to consistently measure length of employment, recruitment, retention and turnover for AHPs in rural and remote areas. Future research could focus on developing a rigorous theory-informed standardised framework, tested for validity, that could be applied across studies. This type of framework could improve reliability and validity when synthesising data across studies and could provide collective evidence to inform practice and policy to improve recruitment, turnover and retention of AHPs in rural and remote areas.

Conclusion

This scoping review based on quantitative evidence described the currently existing data in relation to length of employment, and significant factors and costs associated with recruitment, retention and turnover of AHPs in rural and remote areas. Studies were diverse in terms of sample, methodologies and location, although most studies were based in Australia. This scoping review highlights that, generally, the length of employment of rural and remote AHPs is short, and available costs data indicates significant costs associated with workforce turnover. However, further research is required to understand costs associated with recruitment, retention and turnover, due to significant gaps in the literature. Numerous personal and organisational factors impacted recruitment, retention and turnover, although findings were sometimes contradictory, and therefore these factors need to be further examined in detail if they are to be used to direct future policy. It is also recommended that a framework is developed to standardise the measurement of stay, recruitment, retention and turnover of AHPs in rural and remote areas to enable rigorous evaluation of workforce initiatives. The use of this framework would add consistency and extend the evidence base to better inform future policy and practice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Catherine Brady at the Flinders University Library Services for assisting with the searches for the scoping review.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2015 - Rural health activism over two decades: the Wonca Working Party on Rural Practice 1992-2012