Introduction

Australians in rural and remote regions experience poorer health and welfare outcomes related to living in their geographical location than individuals in major urban centres1. Rural and remote locations have inequitable access to services and resources, which limits the community’s opportunities to take care of themselves, advance themselves with work or learning, or enhance themselves by engaging in meaningful activities that contribute to their enjoyment and quality of life1-3. The percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is also statistically higher in remote and very remote areas1, with governments making a commitment to reduce health inequities for these communities4.

There is no global consensus for the definition of ‘rural’, but rural health has been differentiated from remote health in that remote populations are more isolated, smaller and dispersed, along with economic differences between rural and remote areas, which leads to higher socioeconomic disadvantage in these areas5,6. Despite this, these terms are debated and used interchangeably in Australian contexts5. The Australian Government maps the health workforce using the Modified Monash Model (MMM) on a seven-point rating scale or rurality7. The literature in this review incorporated regional, rural and remote populations as per any rating system utilised.

Rural and remote health in Australia relies on a consistent workforce to service the population. Attracting and maintaining health professionals to work in rural locations is a well-documented and ongoing issue8, with recruitment and retention the focus of many workforce strategies. Durey and colleagues define workforce retention as ‘the minimum length of stay between commencement and termination of employment’ (p. 2)8. Allied health professionals represent approximately one-third of the Australian health workforce9.

An allied health professional (AHP) in Australia refers to a university-trained practitioner who has a defined core scope of practice and is regulated by a national professional organisation with a code of ethics or conduct9. Allied Health Professions Australia (AHPA) delineates AHPs as professionals who ‘provide a broad range of diagnostic, technical, therapeutic and direct health services to improve the health and wellbeing of the consumers they support’ (paragraph 1)9. Generally, it is agreed on that the medical and nursing professions are not considered allied health9. As there is no universally agreed upon definition of an AHP8,9, the Australian Health Insurance Act 197310, specifically the Health Insurance Determination 202411, list of AHPs was utilised for this review. The professionals listed in the Act are outlined in Box 1 and literature on these professions was included in this review9,11,12.

Jesus et al. found a perceived lower priority for allied health research compared with medical workforce studies13, meaning allied health was, and continues to be, under-represented in the refereed literature regarding recruitment and retention in rural and remote Australia and highlighting the need for further peer-reviewed literature to understand these concepts. The present study aimed to understand and summarise the current literature related to recruitment and retention for AHPs, therefore addressing this gap. Previously published systematic reviews did not adequately address the research question posed because they included global research14, different health professions14,15, demographic data trends16, or were specific to a mature-aged population17. No published protocols for similar reviews were found and a gap in the literature remained.

Therefore, the purpose of this review was to investigate the current literature using a scoping review approach to identify, describe and address workforce recruitment and retention issues and initiatives for AHPs in rural and remote Australia.

Box 1: Allied health professionals listed in the Australian Health Insurance Act 1973 (updated November 2023)

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioner, Aboriginal health practitioner or Torres Strait Islander health practitioner Audiologist Chiropractor Dietitian Exercise physiologist Occupational therapist Optometrist Orthoptist Osteopath Physiotherapist Podiatrist Psychologist Speech pathologist |

Methods

A scoping review methodology was chosen to identify the scope and size of the available literature while remaining systematic, transparent and replicable18-21. This methodology allows for mapping key concepts, may assist in clarifying definitions or the boundary of a topic, and allows for the inclusion of a range of study designs while also acknowledging that the research question is not precise enough to warrant a systematic review20,21.

A critical appraisal was conducted to add depth and rigour to the review18,20. The PRISMA extension for scoping reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR) was followed (see Supplementary File 1)19,22, but a review protocol was not published. The steps of Arksey and O’Malley’s21 stages of a scoping review that were informed by the PRISMA-ScR were completed.

Step 1: identifying the research question

The selected research question was: How does the current literature identify, describe and address workforce recruitment and retention issues for AHPs in rural and remote Australia? The research question was chosen to identify factors affecting the population while also ensuring a feasible review that allows the question to be answered given the evidence available23. It also maintained a wide approach in definitions, allowing for a breadth of coverage of the topic21.

Step 2: identifying relevant studies

Grey and peer-reviewed literature were included in this review. To encompass all relevant studies, 14 databases were utilised (see Table 1). Concepts searched included ‘allied health’, ‘Australia’, ‘rural’ or ‘remote' location and ‘employment’ using multiple search terms, specific database terms, MESH terms, keywords and subject headings (see Supplementary File 2). Boolean operators, phrase searches and truncation were included as appropriate for each database. Three authors developed the research question and search strategy. The search was developed and trialled in Ovid Medline, then translated to other databases with keywords or MESH terms updated. An experienced health sciences librarian was consulted in the development phase to ensure methodological rigour and reduce bias19.

A targeted grey literature search was completed in Google with the words ‘rural and remote allied health workforce recruitment and retention’ in an attempt to capture material that was not registered in academic databases, such as government documentation. Five content-specific, key stakeholder websites were examined by Google Advanced Search for relevant grey literature (see Table 2). For all searches, the first 50 items were screened using their web link title and/or full text of the website, and only those meeting study inclusion criteria were included in the analysis phase.

Date limits of 2013 to 2024 were applied, which aligns with the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in Australia24. This date range was chosen to acknowledge the significant impact the NDIS has had on health service policy and delivery throughout Australia and to limit literature to an approximate 10-year period. It was acknowledged that seeking Australian literature would likely result in English publications, so no language criteria were applied. Reference lists of retrieved publications were examined to identify additional relevant sources21.

Table 1: Peer-reviewed literature search strategy

|

Databases searched |

|

|||

|

Key concepts and associated search terms |

Allied health | Australia | Rural & Remote | Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioner Aboriginal Health Worker Allied health Allied health profession / service / occupation / practitioner / work Audiology Chiropractic Dietetics Exercise Physiology Nutrition Occupational therapy Optometry Orthoptics Osteopathy Physiotherapy Podiatry Psychology Social Work Speech pathology |

Australia Australian Capital Territory New South Wales Northern Territory Queensland South Australia Tasmania Victoria Western Australia |

Remote Rural Rural health Rural hospitals Rural population |

Burnout Career Contract services Drive in drive out Employment Fly in fly out Hire Job satisfaction Recruitment Relocation Retention Staff Workforce |

|

|

Inclusion criteria |

|

|||

|

Exclusion criteria |

|

|||

Table 2: Grey literature search strategy

| Organisation name & website | Words searched | Number of results |

Number of items extracted from the top 50 results |

|---|---|---|---|

|

https://www.google.com.au |

Rural and remote allied health workforce recruitment and retention |

1,010,000 |

4 |

|

Google Advanced Search Services for Australian Rural & Remote Health https://sarrah.org.au |

Exact word/phrase: allied health Any of these words: rural remote retention recruitment |

103 |

1 |

|

Google Advanced Search Allied Health Professions Australia https://ahpa.com.au |

Exact word/phrase: nil Any of these words: rural remote retention recruitment |

194 |

4 |

|

Google Advanced Search National Rural Health Alliance https://www.ruralhealth.org.au |

Exact word/phrase: allied health Any of these words: retention recruitment |

1,720 |

5 |

|

Google Advanced Search Indigenous Allied Health Australia https://iaha.com.au |

Exact word/phrase: nil Any of these words: retention recruitment rural remote |

463 |

2 |

|

Google Advanced Search Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care https://www.health.gov.au |

Exact word/phrase: allied health Any of these words: retention recruitment rural remote |

2,920 |

4 |

Step 3: study selection

The first author completed database and grey literature searches across 5 days. The first and second authors conducted title and abstract screening independently to apply inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 1). Conflicts were reviewed, discussed and resolved with the fourth author. The first and second authors again conducted full-text screening independently, with the fourth author reviewing, discussing and resolving conflicts.

Step 4: charting the data

The first and third authors completed data extraction on the included sources using a researcher-developed tool20,21. The tool was trialled on the first four sources, refined with minor additions, and then applied to all remaining sources. The Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT) Version 1.425-27 was applied to critically appraise the quality of literature sources as recommended by the PRISMA-ScR. Authors 1 and 3 independently implemented the tool on four sources to ensure both authors were confident with the use and consistency of results achieved. Author 1 completed data extraction and appraisal of each source, and Author 3 entered data into the extraction tool and reviewed the critical appraisal. Any conflicts were discussed until a consensus was reached. This methodology was chosen owing to Author 1’s familiarity with the literature sources, and rigour was ensured as both authors extracted and reviewed all data.

Step 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

A narrative synthesis methodology was chosen because the included sources were too broad in scope and type to allow for a meta-analysis28. Further, a text-based synthesis allowed for a more appropriate representation of the data28. A narrative synthesis involves the ‘organisation, description, exploration and interpretation of study findings and the attempt to find explanations for (and moderators of) those findings’ (Lesson 2 slides)29. The PRISMA-ScR guidelines recommend the synthesis of results, and the authors opted to do so and descriptively map the results as part of this review20. The first author completed the final stage of collating, summarising and reporting the data, with input from all other authors. The fourth and fifth authors provided oversight during this process, including discussions and participation in completing the narrative synthesis. All authors provided input to the synthesis of themes, with multiple discussions and theme adaptation until consensus was reached between all authors. The results were organised and presented as a thematic narrative21.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required for the purpose of this scoping review, because all data had already been published. The authors identified no conflicts of interest or bias.

Results

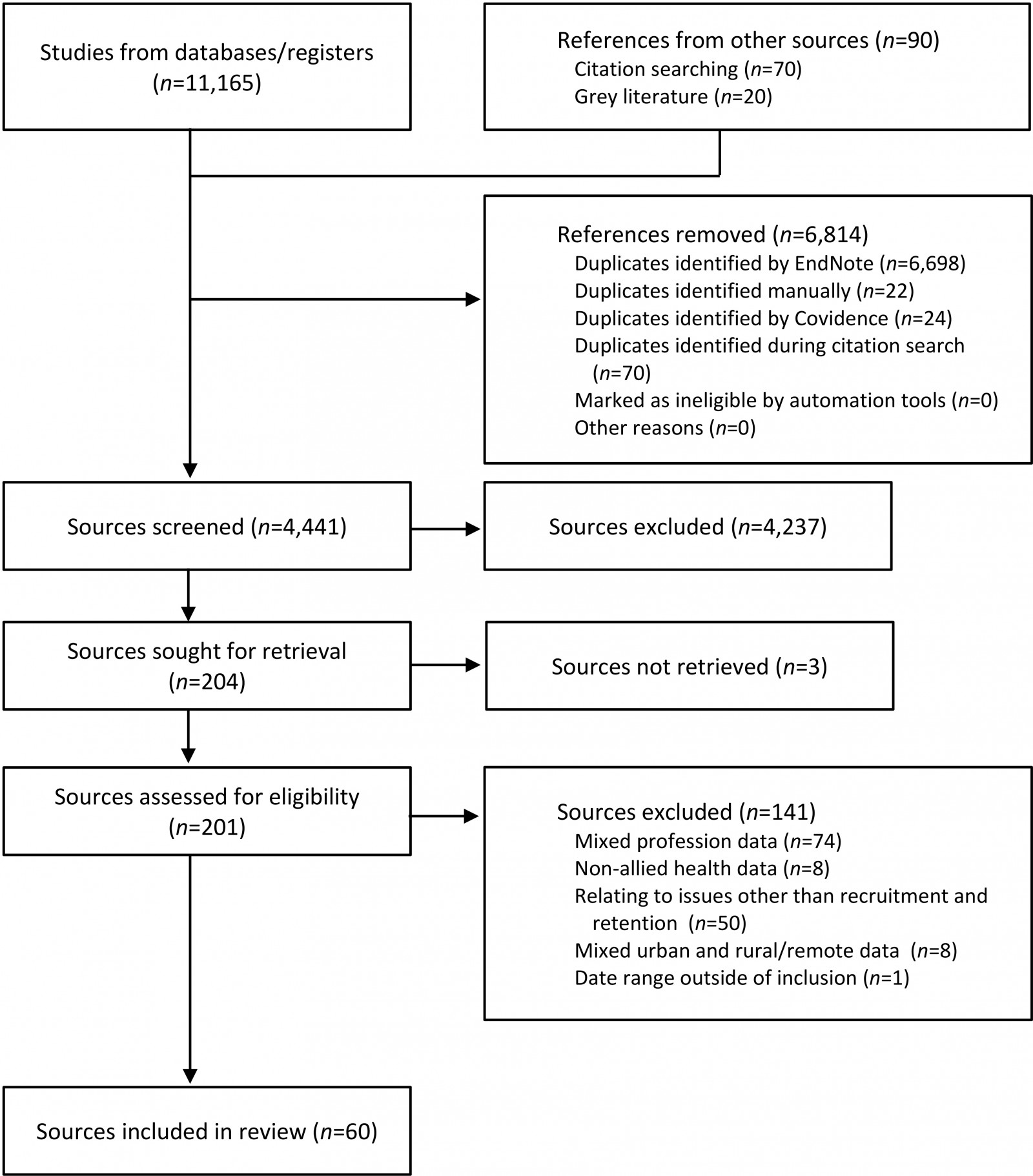

Database searches were conducted on 6 February 2024, and grey literature searches between 3 and 17 May 2024 by the first author. Results were exported to Endnote, duplicates were removed, remaining results were uploaded into Covidence30 and further duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening of 4,441 sources, then a full-text screening of 201 sources, was completed. Many sources were excluded because they did not align with the research question or focused on allied health professions that were not included in our list. Reference lists of the included studies were also screened for further relevant sources, but only duplicate sources were found. Two sources were deemed ineligible and removed at the critical appraisal stage. A final 60 sources were included in the narrative synthesis phase of the scoping review. The PRISMA diagram in Figure 1 details this process.

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram.

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram.

Critical appraisal

Critical appraisal was conducted using the CCAT25-27. While it is acknowledged this tool is not the most appropriate for grey literature, it was selected for consistency of appraisal of all the selected sources and is considered to be a more accurate rater of reliability than an informal appraisal of research25. To use the tool, reviewers rate eight sections of a literature source that are typically found in health research with a score of one to five26,27. A total score is calculated, and reviewers can highlight pertinent details about the source on the overview page26,27.

Table 3 presents the CCAT appraisal scores, including section scores, overall score and overall percentages8,31-89. Of the 60 sources, 33 scored above 60%, highlighting that many sources were of high quality. Twelve sources were rated poorly; however, the authors note that many were grey literature sources that do not typically adhere to the academic writing conventions required to score highly on the CCAT. Data synthesis was completed for all sources but with themes more heavily obtained from sources that scored highly on the CCAT and contained more detailed or peer-reviewed information.

Table 3: Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT) results

| Reference | Preliminaries | Introduction | Design | Sampling | Data collection | Ethical matters | Results | Discussion | Total | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 17.5 |

| 32 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 36 | 90 |

| 33 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 40 |

| 34 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 19 | 47.5 |

| 35 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 38 | 95 |

| 36 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 28 | 70 |

| 37 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 38 | 95 |

| 38 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 32 | 80 |

| 8 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 50 |

| 39 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 39 | 97.5 |

| 40 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 32.5 |

| 41 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 31 | 77.5 |

| 42 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 34 | 85 |

| 43 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 37.5 |

| 44 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 38 | 95 |

| 45 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 39 | 97.5 |

| 46 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 27.5 |

| 47 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 16 | 40 |

| 48 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 39 | 97.5 |

| 49 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 35 | 87.5 |

| 50 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 37 | 92.5 |

| 51 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 40 | 100 |

| 52 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 35 | 87.5 |

| 53 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 39 | 97.5 |

| 54 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 25 |

| 55 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 25 | 62.5 |

| 56 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 38 | 95 |

| 57 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 40 | 100 |

| 58 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 40 |

| 59 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 40 | 100 |

| 60 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 22.5 |

| 61 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 34 | 85 |

| 62 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 31 | 77.5 |

| 63 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 30 | 75 |

| 64 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 34 | 85 |

| 65 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 35 | 87.5 |

| 66 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 45 |

| 67 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 35 | 87.5 |

| 68 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 25 |

| 69 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 22.5 |

| 70 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 14 | 35 |

| 71 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 17.5 |

| 72 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 17 | 42.5 |

| 73 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12 | 30 |

| 74 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 45 |

| 75 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 26 | 65 |

| 76 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 21 | 52.5 |

| 77 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 21 | 52.5 |

| 78 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 21 | 52.5 |

| 79 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 17.5 |

| 80 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 13 | 32.5 |

| 81 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 25 |

| 82 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 22.5 |

| 83 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 22.5 |

| 84 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 28 | 70 |

| 85 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 29 | 72.5 |

| 86 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 31 | 77.5 |

| 87 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 37 | 92.5 |

| 88 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 36 | 90 |

| 89 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 35 | 87.5 |

Data charting

The first and third authors conducted data charting (see Supplementary File 3 for full extraction results). Table 4 summarises the source characteristics.

Table 4: Summary of source characteristics

| Source characteristics | Results |

|---|---|

|

Source review type |

Peer reviewed n=45 Non-peer reviewed n=15 |

|

Type of source |

Research article n=27 Review article n=5 Project report n=5 Webpage n=5 Research report n=3 Editorial n=3 Online magazine n=3 Conference article n=2 Report n=1 Opinion piece n=1 Conference abstract n=1 Communique n=1 Consultation response n=1 Press release n=1 Letter n=1 |

|

Geographical locations featured |

National n=19 New South Wales n=18 Queensland n=6 Victoria n=4 South Australia n=3 Tasmania n=1 Western Australia n=1 Mixed states n=6 Unclear n=2 |

|

Study design type |

Qualitative studies n=11 Cross-sectional design n=7 Mixed or multimethod n=4 Survey n=3 Interview n=2 Case study n=2 Longitudinal study n=2 Project n=2 Quantitative study n=1 Other methodologies n=10 No study design / Not relevant n=16 |

|

Professions involved |

Allied health / no exact profession specified n=22 Physiotherapy n=16 Occupational therapy n=11 Psychology n=9 Speech therapy n=7 Dietetics and nutrition n=4 Podiatry n=4 General health professionals and stakeholders n=4 Chiropractors n=2 Mental health professionals n=2 Social work n=2 Audiology n=1 Exercise physiology n=1 Optometry n=1 Osteopathy n=1 Students n=7 |

Narrative synthesis of results

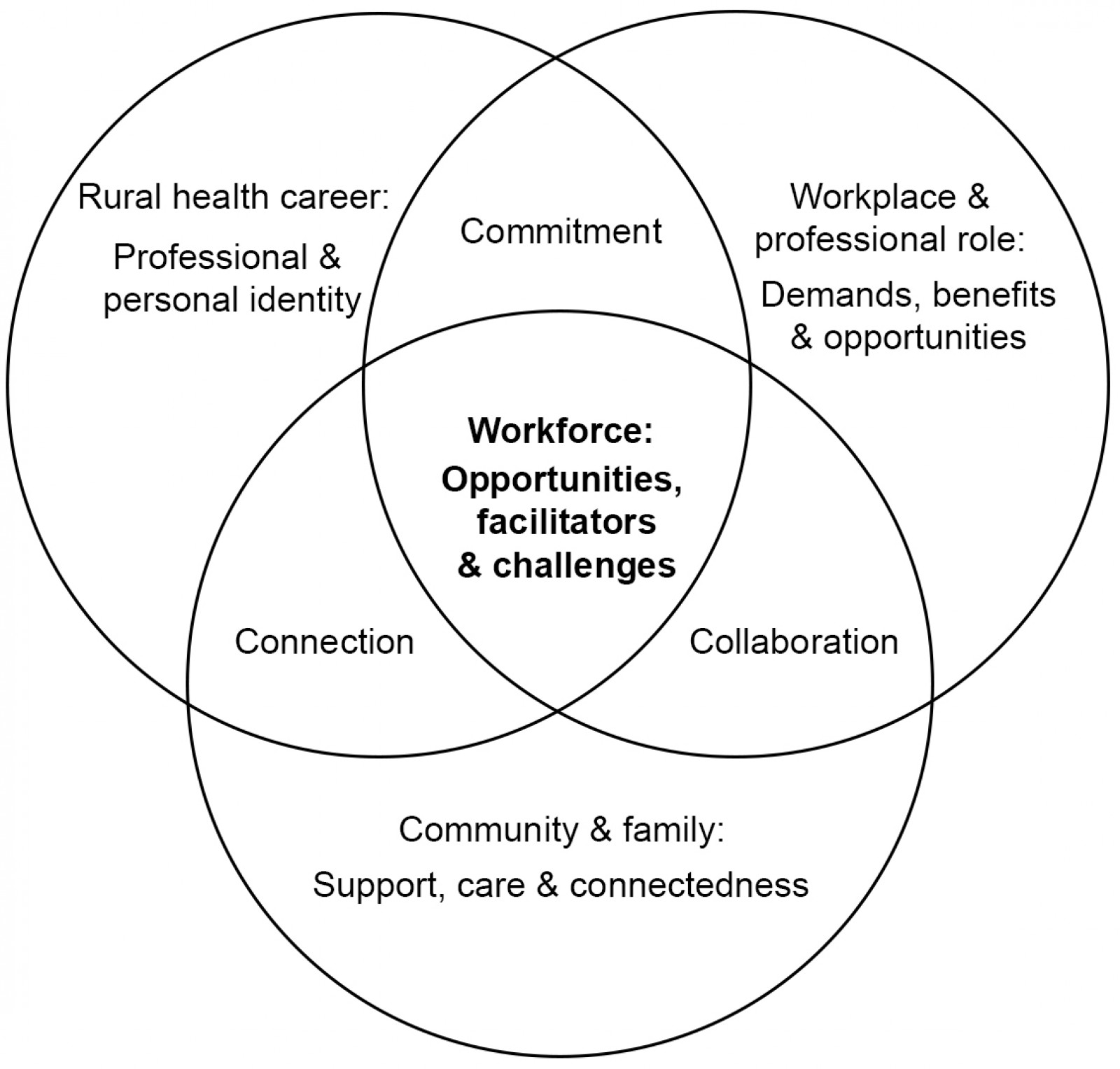

The narrative synthesis was based on data extraction and included data coding, data categorising and the development of themes in an inductive manner90. The themes are represented as a model90 in Figure 2, which depicts three intersecting circles. The theme Workforce: opportunities, facilitators and challenges is at the centre of the model. The theme of Connection, Commitment and Collaboration is at each intersection of the circles: Rural health career: professional and personal identity; Workplace and professional role: demands, benefits and opportunities; and Community and family: support, care and connectedness. Table 5 summarises the themes, subthemes, illustrative quotes and sources related to each theme.

Figure 2: Model representation of narrative synthesis themes.

Figure 2: Model representation of narrative synthesis themes.

Table 5: Themes, subthemes and illustrative quotes

Note: CPD, continuing professional development; HDR, higher degree research; LHD, local health district; NWRH, North and West Remote Health; PPP, public private partnership.

|

Theme |

Subtheme & description |

Sources relevant to the theme |

Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Workforce: opportunities, facilitators and challenges |

Encompasses literature that identifies, describes, quantifies or explores the concepts of recruitment, retention, workforce data, sustainable health services, clinical outcomes and stronger workforce outcomes. |

1. When asked about job satisfaction, almost all reported high levels of satisfaction (p. 227)40. 2. Participants commented on the benefits for communities in which there is now a physiotherapist employed. Having health professionals in rural communities meant that people and families did not have to travel to access a physiotherapy service. Also, by ensuring vacant positions are filled, earlier transfer from the large regional hospital to receive treatment in the rural hospital closer to home was possible (p. 710)88. 3. More emphasis on the rewarding aspects of working in rural areas as well as addressing the more challenging aspects is needed to attract more hearing health professionals to areas where they are so desperately needed (p. 389)45. 4. Themes identified in the data included challenges with re-establishing services that had been vacant for extended periods [and] managing the workload once services were reestablished (p. 710)88. 5. [The Statement] provides an opportunity to listen to rural and remote communities and to respond with a model of health care that meets their needs, when they occur and in their communities (p. 15)84. |

|

|

Rural health career: professional and personal identity |

Own-grown rural origin Living in a rural or remote location prior to commencing professional study or employment. |

6. Own grown allied health professional workforce model (p. 2)73. 7. Rural background was a weaker predictor than expected but this may have been due to the relatively small number of participants who had been educated in rural areas or considered themselves from a rural background (p. 108)35. 8. Podiatrists who had a rural background were … more likely to work rurally … [however] there was no interaction between growing up in a rural location and undertaking a placement in a rural setting (p. 5)37. |

|

|

Values Underlying values, attitudes, personality and motivations impact when, how, where and what AHPs choose to do for work. |

9. The scarcity of eye-care practitioners in rural areas is not due to a shortage of personnel, but rather is related to the preferences of practitioners to work in urban areas (p. 568)46. 10. They valued autonomy and flexibility (p. 227)40. 11. These insights include positive self-assessed fit with remote, realistic construing of the remote environment, overall satisfaction with their current work position, and personality traits that appear to support success in remote (p. 11)63. 12. Reward Dependence (warmth and social attachment) and Self Directedness (responsible and resourceful) all of which are known to contribute to coping in remote environments (p. 9)63. |

||

|

Education Encompasses exposure to allied health professions during schooling, completion of higher education professional qualification courses, and engagement in placements. |

13. The educational opportunities students receive during their placement create positive perceptions of working in a rural setting (p. 205)58. 14. Service learning placements are providing allied health services in small rural towns where previously there have been limited or no allied health services (p. 6)67. 15. The student immersion placement program demonstrates a positive impact on rural and remote workforce outcomes for new graduates (p. 665)66. 16. An increased exposure to a rural location has improved the recruitment of dietetic staff in the local rural area (p. 121)33. 17. This points to a misalignment between the current HDR training model and the needs, prior experiences, and expertise of a diverse and non-traditional student cohort (p. 308)34. |

||

|

Career pipeline Refers to the professional’s life or career stage including graduate, early career, mid-career and late career. |

18. The rural health pipeline adapted for allied health professionals has emerged as a useful conceptual tool in recruitment and retention … opens the door to developing recruitment and retention strategies that reflect the various stages allied health professionals enter rural practice along with differences in age, gender, professional needs, social context, cultural background and career stage (p. 8)8. 19. The promotion of rural work environments needs to target different aspects for professionals at different career stages (p. 110)35. |

||

|

Multi-skilled competencies Competencies or skills that AHPs need or benefit from when working in rural areas, and which contribute to their professional identity. |

20. New graduates were viewed as likely to fail, or be overwhelmed given the additional responsibilities that working as a lone clinician or in a small team can entail (p. 275)61. 21. Therapists commented that to practice in a rural area, one must be multi-skilled (p. 227)40. 22. The seven competencies were: managing continuing professional development, managing supervision, managing the lack of other services, managing dual relationships, managing visibility, managing confidentiality; and having an appreciation of the rural context (p. 275)89. 23. The data on the number of services provided suggest that regional private [occupational therapy] practitioners tend to be generalists (p. 283)48. |

||

|

Professional networks Supports and maintains professional identity, and can include colleagues, multi-disciplinary teams, organisation staff, supervisors, mentors, peers, and broader professional relationships. |

24. Though workforce retention was not an initial aim of the Catalyse Mentorship Program, we believe that providing strong professional networks in regional Australia may prove to be one initiative, in addition to others (p. 8)65. 25. Our study, like others, suggests that access to CPD and professional support is particularly crucial in retaining allied health professionals in an early career stage (p. 11)42. 26. The Allied Health Rural Generalist Pathway was raised as a positive way of overcoming limited supported graduate and early career opportunities (p. 1)72. 27. Networking between professionals also enhanced professional credibility (p. 386)45. 28. Peer group supervision was successful in supporting isolated workers to perform their everyday professional roles (p. 273)49. |

||

|

Workplace and professional role: demands, benefits and opportunities |

Professional role and its diverse demands Relates to the AHP’s role and the demands or activities required to fulfil that role. |

29. These rural service providers were already managing services that were in high demand. This increase in service demand threatened the viability of services as participants struggled to meet it (p. 6)38. 30. Telehealth should not seek to replace existing services but to enhance access where no accessible services exist or where specific or specialised services are not available in an area (p. 2)81. 31. Our research revealed that it was not distance travelled, per se, that was problematic for retention. Rather, it was nights required to be spent away from home (p. 11)42. 32. This finding could indicate a demand on rural practicing podiatrists to split their workload across multiple settings (public, private and outreach) to meet the needs of the population groups living in these areas (p. 7)87. |

|

|

Remuneration and incentives Considers the employee’s contractual package, including salary/financial benefits, professional development allowances, leave entitlements, accommodation assistance, or other incentives offered by the employer. |

33. Remuneration was not the main attribute that will keep these groups of AHPs practicing in a rural area (p. 11)42. 34. An incentive package might include financial and non-financial support in the form of: professional development; accommodation assistance, and help with relocation costs; additional personal leave; family travel assistance; and a rural or regional allowance or bonus, if relevant to the advertised role (paragraph 9)68. |

||

|

Work culture and environment Includes social, physical, policy, financial, resources, training and value factors of an organisation or workplace. These factors are related to the employer and how their systems or supports affect the AHP’s employment. |

35. The quality of the clinical environment was a strong attractor for many participants (p. 158)62. 36. The interdisciplinary approach allowed clinicians to work to the top of their scope of practice and created an environment for information sharing, continuity of care and increased health system efficiencies (paragraph 7)77. 37. Building on existing initiatives and programs is likely to be more cost-effective, quick to implement and has the advantage of utilising current infrastructure (p. 16)80. 38. Freedom to use professional judgement was the most influential of the six job attributes (p. 10)42. |

||

|

Professional development opportunities Includes challenges and barriers to access and the positive impact on AHPs’ staff retention. |

39. Encourage attendance of CPD, support a research culture and best practice (paragraph 8)79. 40. Become a learning organisation (paragraph 6)79. 41. Our study, like others, suggests that access to CPD and professional support is particularly crucial in retaining AHPs in an early career stage (p. 11)42. |

||

|

Health system policy and planning The health system overarches the allied health workforce. Policy and planning can involve government, organisations, professional boards or other peak bodies, or may extend beyond the health system. |

42. Urban centric policy and planning for health professionals often fails to address relevant issues for rural practice that can negatively affect recruitment and retention along the pipeline (p. 6)8. 43. Additional investment in access for rural and remote consumers is likely to provide very significant health benefits for communities with the highest rates of chronic illness and reduce costs to the health system (p. 3)81. 44. Recruitment and retention of new therapists into rural and remote areas, and the provision of added supports for existing service providers, appears critical to avoid the failings of the NDIS in rural areas (p. 8)38. 45. Government or organisational policies should avoid one-size-fits-all approaches to multidisciplinary care teams, and instead allow primary care practice to adapt to their specific contextual circumstances (p. 12)84. |

||

|

Community and family: support, care and connectedness |

Community context Considers the local environment where an AHP works, including the environment’s physical features, social connections, clinical relationships, and involvement/impact of the community. |

46. When developing an allied health workforce, especially in rural and remote communities, it is critical and more important to develop and build on the local community strengths and capacity, not just at a service specific level but with individuals, families and groups that need to access services. This is the most efficient, effective, sustainable and person-centred approach (p. 17)74. 47. One participant spoke of her decision to close her books and discussed the ethical dilemma this can present in smaller rural communities. She stated: ‘I find it extremely difficult to say no to someone … I live and work in my small community so I know everyone, they know me’ (p. 6)38. 48. Engagement with community is essential and this was a key factor to the project’s success (p. 15)74. 49. Overwhelming increases to service demand with the NDIS were affecting not only the perceived identities of rural service providers in their workplace, but also their perceived sense of self as members of the communities (p. 6)38. |

|

|

Belonging in place Describes the strong connection with a rural/remote location that AHPs have. |

50. Belonging in place involves the establishment, over time, of an affective connection to or a ‘sense of fit’ in a particular place, which is facilitated by the social interactions experienced in that place … We have explored concepts of sense of place, place attachment, and belonging-in-place and suggested these concepts hold considerable potential for investigation of rural health workforce retention (pp. 3–5)47. 51. To attract AHPs who are the ‘right person’ for the work and place context, the author recommended that both services include a standard interview question to help determine candidates’ ‘fit’ for the service and the place/town (p. 4)64. |

||

|

Lifestyle and social support Refers to the way an AHP chooses to carry out their life (what, how and why they do activities), and the AHP’s relationships (family, friends and community members). |

52. All participants noted that social integration into the community was important in a small township, and that being known and having a strong sense of belonging to the community was rewarding (p. 386)45. 53. Feelings of alienation and social disconnection, especially in the first year of moving to a rural town, were common (paragraph 10)70. |

||

|

Support and challenges for family Family was identified to positively and negatively impact the workforce. |

54. The stayers with no plans to leave were usually in middle adulthood and were raising families or planning to start a family soon (paragraph 11)70. 55. Of those not open to working in a rural location, 12 participants cited family reasons for their stance (p. 138)39. 56. 25% reporting being restricted in their employment or usual hours of work because of lack of available childcare (p. 229)41. 57. While missing family when away was described as a challenge, an advantage of the time away was the opportunity for personal space, and time away from one’s family and partner (p. 224)52. |

||

|

Commitment, connection & collaboration |

Commitment Reflects the varying interaction types and highlighted the need for equal investment in the employer-employee relationship. |

58. Sustainable, high functioning and agile rural and remote multidisciplinary health teams form when team members work effectively to their full scope of practice, employ their skills, knowledge and experience, value diversity and commit to the delivery and provision of culturally safe and responsive practice (p. 14)84. 59. Participants indicated that the PPP model relied upon ‘give and take’ from all parties involved and that mutual respect was integral to the model’s success (p. 337)53. |

|

|

Connection The connection between AHP and their community was vital to workforce success; to ensure AHPs contribute to and benefit from their involvement in the wider society where they work and live. |

60. The Gidgee Healing Aboriginal health workers played a pivotal role in the delivery of culturally safe care, by being the conduit between the communities and the NWRH allied health team (paragraph 8)77. 61. Establishing social connections was a priority issue for most AHPs who had relocated (p. 8)64. |

||

|

Collaboration Collaboration occurred between the community and workplace when stakeholders created sustainable, effective health care and appealing locations to encourage AHP to work and live there. |

62. Given … the part-time shared supervisor resource across a geographic area of over a large portion of 125 000km2 area of the LHD … a high level of collaboration was necessary and also logistically challenging and might reflect a resourcing deficit (p. 717)88. 63. It is necessary to build the rural therapy workforce actively and purposefully, not only in the private sector but in collaboration with all disability sector stakeholders (p. 229)40. 64. Rural communities cannot address these barriers alone. It is important that governments, universities, accrediting agencies and colleges work to ensure that the perceptions and considerations of professional and financial barriers to working rurally are overcome (pp. 311–312)31. |

Workforce: opportunities, facilitators and challenges

The core theme of the literature was Workforce: opportunities, facilitators and challenges. This theme encompasses literature that identifies, describes, quantifies or explores the concepts of recruitment, retention, workforce data, sustainable health services, clinical outcomes and stronger workforce outcomes. Sources discussed persistent recruitment challenges related to senior staff88, job uncertainty and insecurity88, burnout84, professional isolation or ‘outsidedness’ (p. 710)36,49,84 and challenges with re-establishing services88. Reasons for leaving positions were multifactorial78. Opportunities and facilitators included factors such as multidisciplinary health teams84, peer group supervision49 and listening to communities84. Overall, job satisfaction was mentioned in several sources36,40,54,65,70. Key outcomes of recruitment and retention that impact the community were also highlighted, including families not needing to travel for services, being able to transfer closer to home earlier in recovery and having providers who were known and trusted in the community88, which is detailed in Quote 2 in Table 5.

Rural health career: professional and personal identity

The theme of Rural health career: professional and personal identity speaks to the individual AHP and considers their identity concerning recruitment and retention into the workforce. Personal identity consisted of the Values and Own-grown rural origin subthemes. The Professional identity considers Education, Career pipeline, Multi-skilled competencies and Professional networks.

Own-grown rural origin

This subtheme relates to individuals living in rural locations before commencing their studies or employment, and was described in one study as an ‘own grown allied health professional workforce’ (p. 2)73. Some studies found rural background increased likelihood of working rurally37, while others found it to be a weak predictor35.

Values

Values favoured by AHPs included trust49, sharing49, non-judgemental support49, encouragement49, positive professional affirmation49 and high autonomy of practice35,42,67,89. Management and prestige were the least valued35. Common traits include self-directedness63,89, resilience74,89, resourcefulness89, flexible attitude89, proactive attitude89, confidence89, being comfortable with a high level of responsibility89 and cooperativeness63, while self-determination77 was also noted to be of importance. Further, willingness to step out of the comfort zone89, motivation to embrace the experience51 and appreciation for the rural lifestyle89 were also key traits for successful practice. These traits and values contributed to coping in remote environments and highlighted the drive of AHPs to embrace opportunities and have ‘invaluable experiences’ (p. 448)51.

Education

Several articles commented on the relationship between education and the future workforce58,66 (see Quotes 13 and 16 in Table 5), while others acknowledged benefits for communities and students67,72. The barriers to students attending educational courses80, the need for flexible delivery of courses74, for student expectations to be managed before placements67, and the need for working professionals to offer clinical placement opportunities58 were highlighted as challenges. Higher-degree research opportunities were also noted to be ‘misaligned’ in rural areas (p. 308)34 (see Quote 17 in Table 5).

Career pipeline

The application of the rural health pipeline to allied health is a relatively new concept that assists with understanding the complex interaction of factors impacting the workforce8,80 (see Quotes 18 and 19 in Table 5). Workforce proportions showed a more even distribution of AHPs at each career stage in rural areas compared with remote areas where the career stages were more heavily weighted towards early career professionals75. Workforce profiling was argued to assist with understanding work and social conditions that influence recruitment and retention decisions41. Family-friendly work conditions improved retention for early and mid-career professionals, while late-career professionals were retained by supporting lateral career progressions78.

Multi-skilled competencies

AHPs were shown to have a range of competencies that were prevalent or required for work in a rural and/or remote location (see Quotes 21 and 22 in Table 5). Generally, having a local knowledge base89, recognising rural health issues58 and managing ethical dilemmas52 was required, with this often occurring through practice reflection49. For some roles, a knowledge of Indigenous cultures89 and the ability to work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were identified85. Preferred self-management skills included a focus on scheduling52, juggling priorities49, managing additional responsibilities61, managing fatigue52, being adaptive67 and adapting interventions89.

Emotional competency was also highlighted, with words used to describing this including: confidence56, emotional toll45, managing stress59, persistence63, coping63, professional sustainability49, feeling beyond their depth38, emotional effort51 and acknowledgement of the culture shock for newly recruited staff51. Overall, a generalist skill base48, a ‘diverse knowledge base’ (p. 275) 89, a comprehensive skill set53 and the ability to be multi-skilled40 were commonly mentioned (see Quote 23 in Table 5).

Professional networks

The challenge of professional isolation in the rural/remote environment was a prevalent discussion throughout the literature31,40,45,49,55,56,78,84,88. However, peer engagement36,40,49,53,55, professional support37,45,46,52,53, and camaraderie51 were also highlighted as protective factors. Professional networks were enhanced through peer support including group supervision49, development of a ‘buddy system’ in the workplace 55, having regular contact from onsite clinicians55, unstructured mentorship59 and using multidisciplinary teams84. More formally, expanding networks was achieved through development of public-private partnerships53, arranging staff supervision55, group supervision models76, and structured mentorship59,65. Finally, engagement in the Allied Health Rural Generalist Pathway (AHRGP) also allowed clinicians to develop their professional network72 (see Quote 26 in Table 5).

Workplace and professional role: demands, benefits and opportunities

This theme covered aspects of employment-related literature, such as small-scale factors related to AHPs’ employment in Professional role and its diverse demands and Remuneration and incentives. Medium-scale factors included the Work culture and environment and Professional development opportunities. On a large scale, Health system policy and planning influenced the workplace and professional role.

Professional role and its diverse demands

Rural or remote roles were considered to be ‘unique’ (p. 448)51, (p. 40)85, (p. 376)86 and ‘tough environments’ with ‘additional responsibilities and heavy workloads’ (p. 275)61. Interestingly, public health sector positions were described as the ‘best employment available in town’ (paragraph 17)70. Common role characteristics included travel42,48,52,74,89, telehealth services31,80,81,87, and high demand for services38,78,85,87, each of which could be a negative or positive, depending on workplace goals and individual preferences. Working across various settings87 or in generic positions61 aligned with the need for generalist skills48,53,89 (see Quotes 29 and 32 in Table 5).

Using professional judgement42, working autonomously35,42 and a diverse caseload32,51,62 were valued role characteristics, and rural and/or remote practice was seen as a positive or rewarding experience32,51. Further literature was found that covered various topics related to describing the professional role and its demands, including descriptions of roles36,37,40,41,48,51,87, descriptions of the service populations46,48, challenges and barriers impacting roles38,51,85,87 and service development projects or innovative approaches that address health inequities and staffing initiatives49,57,71-73,83,88.

Remuneration and incentives

Along with other factors, income was identified by AHPs as a reason to leave a rural or remote position78. Queensland Health and New South Wales Health (see Quote 34 in Table 5) offered financial incentives for recruitment and retention68,69. A public–private partnership created an ‘attractive’ employment package for graduate physiotherapists, as evidenced by the ‘increased number of high-quality applicants’; however, the details were not reported (p. 336)53. One study found generic positions were used to expand the field of potential applicants, leading to difficulty finding suitably skilled or experienced staff, and despite the ‘additional responsibilities and heavy workloads’ associated with rural positions, roles were ‘remunerated at the same level and rates as metropolitan areas resulting in a significant disincentive’ for AHPs (p. 275)61. Lack of paid leave was a reason for podiatrists to leave their profession37, while Aboriginal Health Workers’ low salary levels contributed to their job dissatisfaction36. Interestingly, for fly-in-fly-out employment, remuneration was seen as positive because it compensated for the financial implications of travel52.

Work culture and environment

Authors from the various literature sources suggested ways organisations, employers and managers can create environments to foster positive staff engagement62,77,79, such as a quality clinical environment62, utilising an interdisciplinary approach77, creating a learning environment79 and a culturally safe and responsive environment84 (see Quote 35 in Table 5). For some professions and business owners, working rurally created difficulties in maintaining a commercially viable business45,48, with the utilisation of existing resources within the community as a strategy suggested by one study to address this challenge80 (see Quote 37 in Table 5).

Professional development opportunities

The literature showed that professional development (PD) was crucial for early-career AHPs42 and for staff in generalist positions56. Multiple stakeholders supported use of the AHRGP to address PD needs72,73,80,83,88. Travel and cost of courses were identified as challenges, with access to PD being described as ‘adequate’ (p. 227)40, (p. 229)41.

Interestingly, a study of fly-in-fly-out workers identified access to metropolitan PD as a benefit of this employment type52. Osteopaths also utilised metropolitan areas for training before moving to rural practices62 and, similarly, physiotherapists used secondments to address educational and PD needs86. In general, the literature sources agreed that valuing, encouraging and supporting AHPs to engage in PD opportunities was essential for retention8,42,56,59,68,78,79,83.

Health system policy and planning

Different sources offered suggestions for rural and/or remote-specific health system policies, such as the expansion of Medicare eligibility to allied health items81, expanding medical workforce initiatives to the allied health sector82 and advocating for a dedicated Commonwealth Chief of Allied Health Officer role80. On a smaller scale, supporting additional service providers to reduce negative impacts of the NDIS38, enhancing funding for innovative recruitment models53 and public financing for businesses48 which therefore allows practices to adapt to their specific contextual circumstances84 were suggested (see Quotes 44 and 45 in Table 5). Further policy changes identified included reviewing the registration process for international graduates39, shifting the value of fly-in-fly-out work within each profession52, and developing policy that supports integrated and evidence-based approaches to rural health services54, including the AHRGP83.

Community and family: support, care and connectedness

This theme considered the wider context that influences AHP recruitment and retention. Aspects of support, care and connectedness directly impact the individual and the workplace’s ability to retain AHPs. Four subthemes were explored: Community context, Belonging in place, Lifestyle and social support and Support and challenges for family.

Community context

The community context was vital to successful recruitment and retention but has challenges such as unclear boundaries36, unmanaged expectations38 or inadequate induction to the community52 (see Quote 47 in Table 5).

Belonging in place

The literature discussed facilitators to success such as: ‘community attachment’ (p. 233) 41, encouraging new graduates to ‘connect with the community’ (paragraph 5)79 and for services to ‘respond to the needs of the community’ (paragraph 9)79. Further, authors stated ‘engagement with the community is essential and was a key factor to the project’s success’ (p. 15)74 and suggested that policy should ‘draw … on the nature of rural communities themselves, as solutions’ (p. 2)54. It was noted the sense of community influenced the intention to leave for public sector staff78.

Positive community outcomes included AHPs ‘contributing to the social and economic capital within the rural community’ and creating ‘health services that will be sustainable beyond the time frames’ of their project (p. 715)88. Finally, it was suggested that some aspects of health may be provided by non-health professionals, suggesting AHPs work with community members to develop creative solutions to support clinical healthcare services43. Cosgrove (p. 4)64 described the ‘fit’ for an AHP and suggested recruitment interviews should allow staff to tell if the candidate is the ‘right person’ for the context (see Quote 51 in Table 5). The relationship to an environment was individual and place-specific, with participants strongly associating themselves with outdoor environment activities, such as surfing, bike riding or farming62.

Lifestyle and social support

A love of the rural lifestyle was highlighted by some AHPs41, but rural environments were also seen to offer fewer opportunities for lifestyle pursuits than urban settings35. Adjustment to the geographical isolation and differing cultures were noted as challenges51. Difficulties with the blurring of social roles51, concerns with confidentiality60 and managing multiple relationships61 in a small community were explored. Fly-in-fly-out services overcome these challenges by affording staff social connections away from areas serviced52. It was generally agreed that social disconnection or isolation was a risk when moving to a new location31,53,59,70 (see Quote 53 in Table 5), but strong social support and belonging were valued and were positive indicators of recruitment/retention throughout the career pipeline8,41,45,47,53. Some participants noted the social opportunities were typically very good40, and rural communities were welcoming62.

Support and challenges for family

Regarding family, a lack of childcare restricted working hours, yet professionals with children were less likely to cease work than those without children41. Children’s education31 and spousal employment31,41 were considerations for many AHPs. The New South Wales Government provided remuneration package benefits, including family travel assistance, to address some of these concerns68. Additionally, family-friendly working conditions improved retention rates for early and mid-career professionals78. For fly-in-fly-out workers, missing family events, caring for dependents and returning home for emergencies were concerns, yet having personal space while away was an advantage52 (see Quote 57 in Table 5).

Commitment, connection & collaboration

The themes outlined above broadly explored three groups: the person, the workplace and the community, which intertwine to produce the AHP workforce. Commitment, connection and collaboration explores the complex interactions between each group.

Commitment reflects the need for equal investment in the person-workplace relationship. Face-to-face contact was essential for connection88, and ‘give and take from all parties’ along with ‘mutual respect’ (p. 336–337)53 were key factors for success. AHPs should seek clarification when needed79, promote their skills to managers60 and contribute to networking or sharing in their region52,53,76 (see Quote 58 in Table 5). Busy clinical workloads required commitment from the professional and workplace to allow dedicated time for development activities88.

For managers, commitment referred to the need to be prepared for engagement in human resource activities8,59, be flexible53 and to understand AHPs’ ‘personal clinical strengths and weaknesses’, and to ‘link these with career pathways that may go beyond a limited rural departmental or organisational level’ (paragraph 8)79. A Career Pathway Tool was developed to ‘facilitate more strategic and meaningful career conversations between allied health managers and their staff’ (p. 7)64. For some projects, commitment from the organisation, executive and human resources team was essential64.

Establishing social connections was a priority for relocating AHPs64 and encouraged for new graduates79 (see Quote 61 in Table 5). Well connected AHPs contributed to the social and economic capital of the community88, and personal connections in a town were important factors in their decision to stay61. Further, clinical outcomes were stronger when ‘service providers were known and trusted in the community’ (p. 710) 88. Local staff, especially in some Aboriginal communities, assisted with establishing the connections between the AHP and the community, enabling culturally appropriate care77.

Authors also referred to collaboration as coordination57, partnerships34, and co-design72. Stakeholders in the literature involved in collaboration included: the workplace86, community64,72,74,77, organisation64,72,86, other local health providers52,72,76,77,84, educational institutions31,72,84, government31,80, accrediting agencies31, disability community40 (see Quotes 62 to 64 in Table 5), private practices53,57,88, public health providers53,57,88, other sectors43,73,74,80, the local council64 and funding partners77.

Collaboration was essential for success, or an unplanned benefit of innovative recruitment/retention strategies40,53,54,57,64,72-74,76,86,88. Collaboration also increased understanding of other AHPs’ roles58. Using resources outside the health sector43 and combining resources73 were strengths of collaborative relationships. Cross-agency collaboration, leveraging available training funding, and negotiation of commissioning models and education support generated a critical mass of resources that each agency could not source or allocate independently73.

Discussion

This review synthesises the current rural and remote AHP workforce literature into the themes of a rural health career, the workplace and professional role, community and family, and the commitment, connection and collaborations between each group. This synthesis of evidence supports the 2016 work of Schoo and colleagues, who described the individual, organisational and community domains of their health workforce model, and which provided the basis for their argument that policy could support social capital and social relations approaches to build the rural health workforce54. Both models identify the three main groups that interact, positively and negatively, to produce the rural health workforce; with the current review providing evidence from a wider range of sources to support Schoo’s work.

Contrary to medical professionals targeted with financial incentives, this review showed that AHPs valued other incentives more highly, such as good working conditions and affordable housing8,42. Interestingly, income was identified by AHPs as a reason to leave a rural or remote position78, which may indicate renumeration is less important for professionals during the recruitment phase, but is more highly valued at the stage of considering retention or leaving a role. This was noted to be similar to nursing professionals, who were found to value the demanding role, professional opportunities, PD, lifestyle, management and pay and/or incentive factors91. Internationally, a study in rural Canada identified similar factors of rural upbringing, family and/or personal ties, participation in rural and/or remote education, lifestyle options, financial incentives, personal employment opportunities and spousal employment as strong recruitment factors92, which may indicate similarities and therefore allow for generalisation of Canadian recommendations to the Australian context.

The need for training and support specific to different career stages was highlighted. PD was crucial for early-career AHPs42, and the current higher degree by research (HDR) training model was ineffective at meeting the needs of AHPs looking to further their academic career34. AHPs were creative in building professional networks, including peer engagement36,40, buddy systems55, unstructured mentorship59, engagement in training programs57 and group supervision76. Nancarrow and colleagues (p. 333)93 noted that ‘having proportionally fewer senior staff to supervise and support more junior staff creates challenges in maintaining high clinical standards of care’ and ‘is a loss in professional capacity and knowledge’, which would further exacerbate the development difficulties and professional isolation31,40,45,49,55,56,78,84,88 challenges highlighted throughout this review.

Implications for policy, practice and research

Guerin and Guerin94 explained a ‘one size fits all’ generic solution is unlikely to be effective, and multiple solutions for each location are required to progress the workforce, which was echoed by several sources included in this review8,42,80,84. The results of this scoping review reinforce the recommendation for policy and strategy development to include a range of stakeholders who are impacted by, or who impact, rural and remote recruitment and retention84.

This scoping review identified a range of innovative solutions that are proposed or implemented to address recruitment and retention across rural and remote Australia. Solutions included secondment programs55,86, student placement programs44,66,67, workforce self-assessments71, fly-in-fly-out practice models52, mentorship and peer-group supervision programs65, recruiting international graduates39 and public–private recruitment partnerships53.

Managers and organisations are encouraged to review their current recruitment and retention methods and ensure that support is targeted at key areas of importance for their specific workforce in line with their community needs, strengths and resources46. It is suggested that employers, policymakers and communities investing in recruitment consider the unique values of candidates to determine if they are suited to the specific role and community context51.

During this review, some included studies referred to family31,39,41,52,68,74,78 and excluded studies covered health leadership95-97 factors that impact recruitment and retention. Deeper exploration of these factors was outside the scope of this review and may be an area for further investigation. Long-term workforce studies to assess the impact of initiatives was also suggested as an area for further research50.

Limitations

The chosen allied health definition10,11 and inclusion of only Australian literature are potential limitations because data that may be generalisable to the population may have been excluded. Citation searches or hand-searching key journals may have identified further literature but was not completed for this review21. It is acknowledged that scoping reviews can hold the potential for bias in the way results are presented21, and due to the inclusion of all available evidence (regardless of quality), they may not be the best available source to influence policy or practice18. Further, rural health challenges are not always easily summarised into such reviews98, and this was kept in mind throughout the process. However, this methodology was chosen given the broad research question and the need for an overview of the current literature, which can be vast in scope and type.

Conclusion

This scoping review presents a model of the recruitment and retention literature related to the allied health workforce in rural and remote Australia. The results and presented model emphasise the complex interactions between the professional’s rural health career, the workplace and professional role, and the community and family, which contribute to the workforce’s opportunities, facilitators and challenges. The variety of source types and study designs highlights the breadth of information and research into this topic. Further, inclusion of both grey literature sources alongside research studies provides insights for recruitment and retention initiatives that may be implemented, and is a unique feature of this scoping review in its contribution to the literature. The review also aimed to investigate the needs of AHPs specifically, with exclusion of data relating to nursing or medical professionals.

Further investigation into family factors, health leadership and long-term retention is required to better understand how these dynamic concepts interact. Utilising this AHP workforce model promotes consideration of unique solutions that can be adapted to suit individuals, workplaces and communities in rural and remote Australia. The scoping review stresses the need for commitment from all parties to support, develop and sustain the rural and remote AHP workforces beyond their current or immediate future needs.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gabby Lamb, Liaison Librarian for the Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences at Monash University, for her assistance and input in developing the search strategy.

Funding

This research was conducted for the purpose of a higher degree research study and funded by Monash University through a full-time stipend.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.