Introduction

Allergic rhinitis is a common non-communicable, chronic inflammatory disease of the nasal mucosa with a prevalence as high as 50% in many European countries1,2. Prior research has indicated that patients diagnosed with allergic rhinitis have experienced worse quality of life due to impaired sleep patterns, increased fatigue, depression, and altered physical and social functions3,4. Furthermore, a poor perception of allergic rhinitis symptoms is frequently associated with poor allergic rhinitis control5, deteriorating quality of life even further.

Allergic rhinitis frequently occurs with other conditions such as atopic dermatitis, rhinosinusitis, rhinoconjunctivitis and particularly asthma. Most people with allergic asthma and at least 50% of those with non-allergic asthma have allergic rhinitis6. In light of the frequent co-existence of these two conditions, the ‘one airway hypothesis’ was developed, proposing that rhinitis and asthma are basically one disorder that affects both the upper and lower airways in the majority of the patients7. There is evidence to suggest that allergic rhinitis diagnosis can precede asthma diagnosis8,9 and that, when allergic rhinitis is not treated, it can lead to an increase in asthma morbidity10,11. This is why the Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma guidelines emphasize the importance of simultaneously targeting optimal control of both asthma and allergic rhinitis12.

Few data exist evaluating the control of symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with allergic rhinitis who also have asthma13-17. Most of these studies agree that patients with both asthma and allergic rhinitis experienced poorer disease control13 and quality of life compared to those with asthma13,16,17 or allergic rhinitis alone14. Only one study found that individuals with both asthma and rhinitis did not report a lower quality of life compared to those with asthma alone15. However, the limited number of participants with asthma alone and those with both asthma and rhinitis in this study hindered the ability to make valid comparisons among the groups.

Results from prior research on factors associated with asthma and allergic rhinitis control have highlighted the potential influence of geographical location of residence on the control of these conditions18,19. Taking into account the higher exposure of urban residents to pro-inflammatory factors such as car smoke, chemical products from factories, and processed foods20,21, it can be assumed that the severity of respiratory symptoms is greater than for those living in rural areas. On the other hand, it seems that, due to geographical isolation, lack of infrastructure and possibly less favorable socioeconomic status, populations in rural locations may be more vulnerable to the combined adverse effects of asthma and allergic rhinitis22. Another rising concern in rural and remote regions in many European countries is the availability of GPs, who are among the first healthcare professionals to whom patients refer for symptom control23.

In Greece, where 62.6% of the country is predominantly rural24, there are limited data referring to treatment status and symptom control in individuals with asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis25, and we don’t know if GPs suspect and diagnose allergic rhinitis in patients with asthma. The findings reported in a 2011 abstract showed that allergic rhinitis symptoms adversely affected daily activities and exacerbated asthma symptoms in 72% of the 2700 participating patients with asthma25. Therefore, our primary objective was to compare asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis control among primary care patients in urban versus rural areas. Our secondary objectives included identifying factors that might influence the control of asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this multicenter cross-sectional study, consecutive patients visiting the primary healthcare centers of Crete, Greece (Heraklion, Kastelli, Rodia, Agia Varvara) were invited to participate in this epidemiological survey, during a 3-year period (2020–2022). A convenience sample of individuals with asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis was selected based on availability, willingness and eligibility. We included subjects who (1) were adults (≥18 years), (2) reported a physician-diagnosed asthma and allergic rhinitis or nasal symptoms compatible with allergic rhinitis26, (3) spent most of the week (at least 5 days per week) living or working in the areas where this study was conducted and (4) had not been treated with allergen immunotherapy over the previous 6 years. The exclusion criteria were diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other chronic respiratory diseases, physical or cognitive disabilities that prevented the completion of questionnaires.

Data collection

A standardized health questionnaire was administered to all eligible individuals to obtain information on their demographic characteristics (age, gender, area of residence), smoking status and comorbidities. Information about a patient’s self-reported control of asthma and allergic rhinitis was assessed using various patient-reported outcome measures: the Asthma Control Test (ACT), Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) and the Control of Allergic Rhinitis/Asthma Test (CARAT).

Study tools and outcomes

Control of Allergic Rhinitis/Asthma Test

CARAT has been translated into and validated for the Greek language, with Professor I. Tsiligianni contributing to this process27,28. The Greek version of the CARAT was used to quantify the control of both asthma and allergic rhinitis concurrently in the previous 4 weeks (the higher the score, the better the disease control). It is a 10-item questionnaire containing information about the frequency of upper and lower airway symptoms, sleep impairment, activities limitation and need for more medication: the response options for all the questions follow a four-point Likert scale (range 0–3)29. The CARAT consists of two domains: allergic rhinitis (questions 1–4) and asthma (questions 5–10). The range of the CARAT score is 0–30 (>24 indicating good disease control), with a minimal clinically important difference of 3.530.

Asthma Control Questionnaire

The adequacy of asthma control was assessed with the shortened version of the ACQ (ACQ-6), translated and validated in Greek31,32, which consists of five questions about the most common asthma symptoms in the previous week (night-time waking, symptoms while waking up, activity limitations, shortness of breath, wheezing) and one question about required use of a short-acting beta-agonist for symptom relief in the previous week33,34. The score was computed as the mean of all items (range 0–6), with a lower score corresponding to better asthma control. Values of 0.75 or more indicate well-controlled asthma, and values of 1.5 or less indicate not-well-controlled asthma. Values between 0.75 and 1.5 are considered ‘grey zone’ (partially controlled). A minimal clinically important difference of 0.5 was identified34.

Asthma Control Test

The ACT questionnaire is a self-administered instrument for identifying patients with not-well-controlled asthma. The ACT questionnaire, translated and validated in Greek35, comprises five Likert scale items on a scale of 1 to 5, describing activity limitation, shortness of breath, waking due to asthma symptoms, reliever medication and global judgement of asthma. The overall score for the ACT is calculated by summing the scores for the five items, with a possible score ranging from 5 (poor control of asthma) to 25 (complete control of asthma). Higher scores reflect better asthma control. The ACT cut-off point for uncontrolled asthma was 19 or less36. A minimal important difference of 3 was identified37.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables if normally distributed and as median (25th–75th percentile) if not. Qualitative variables are presented as absolute number (percentage). The study population, based on area of residence, was divided into a rural group and an urban group. For comparisons between groups, a two-tailed t-test for independent samples (for normally distributed data) or a Mann–Whitney U-test (for non-normally distributed data) was utilized for continuous variables, and Pearson’s χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Correlation coefficients were calculated using the Pearson or Spearman’s (for non-normally distributed data) correlation test for the associations between CARAT, ACQ-6 and ACT scores. Internal consistency for all questionnaires was calculated with the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and item-total correlations. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs) were used to calculate correlations between the questionnaire subscales.

To evaluate the associations between questionnaire scores and demographics, comorbidities and medications, we implemented linear regression for the continuous questionnaires scores and logistic regression for the dichotomized scores. All models were adjusted for age, gender, smoking status and comorbidities. We checked multicollinearity among the predictors using collinearity statistics to ensure that collinearity between predictor variables was in the acceptable range as indicated by the tolerance value variance inflation factor. Age was evaluated both as a continuous variable and as categorical groups, with age of individuals classified as either 60 years or less, or more than 60 years. For the purpose of this analysis, the term ‘cardiovascular disease’ referred to any of the following conditions: coronary disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Results were considered significant when p-values were less than 0.05. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v25 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics).

We also used G*Power v3.1 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf; https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower) to perform a posthoc power analysis for the most complex analysis in this study. Our analysis showed that a sample size of 74 participants was needed to detect a medium effect (f²=0.15) with 95% power and a significance level of 0.05. To account for a potential 20% dropout rate and the need for 74 participants in the most complex analysis, we set a target sample size of 88.

Ethics approval

All participants received information about the objectives of this study. The study was approved by the University of Crete ethics committees (Protocol No. 114/27.06.2019), and signed informed consents were obtained from all the participants before recruitment.

Results

Patient characteristics

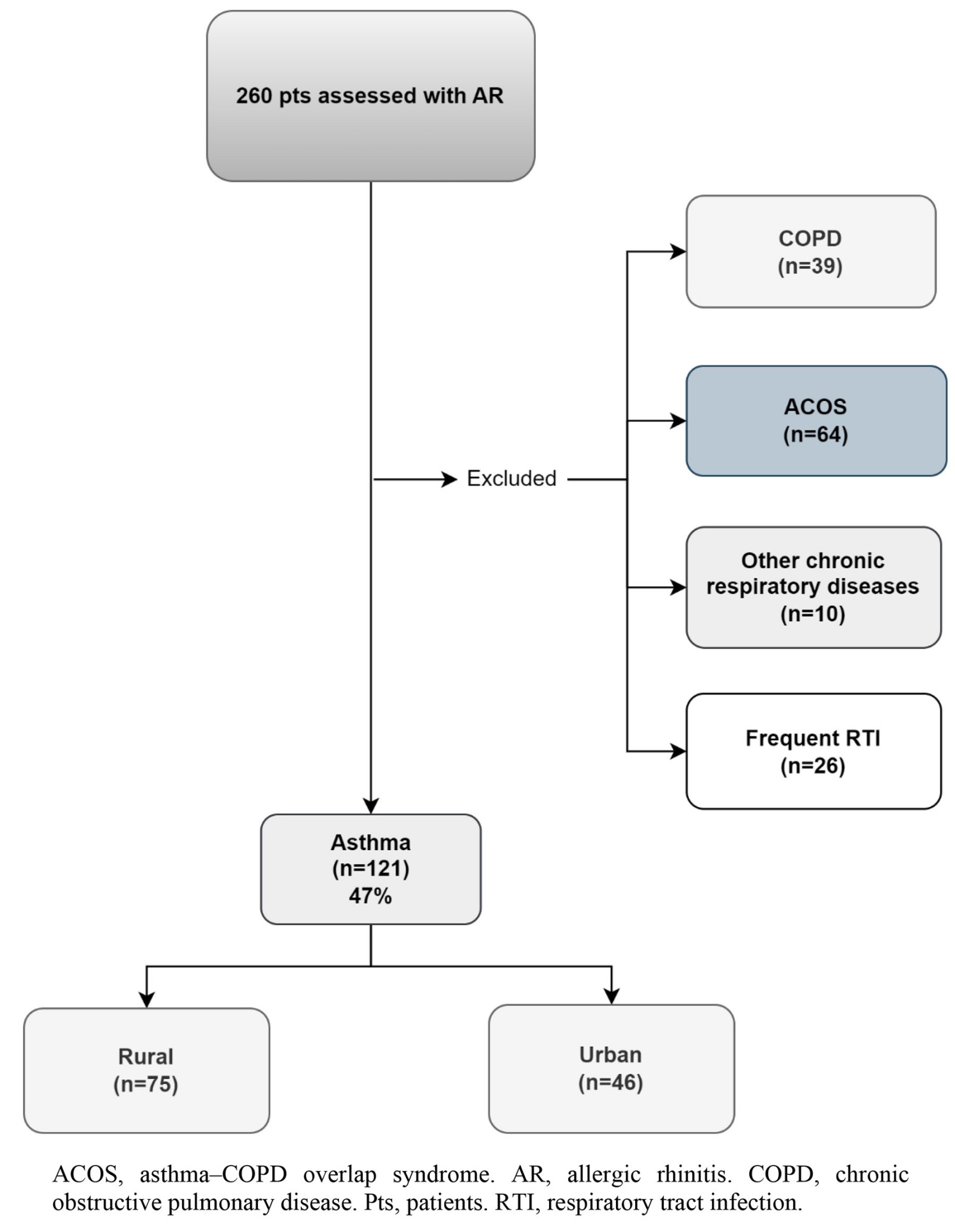

A total of 121 participants with asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis (mean age 50 years, 33% male) were included (response rate 121/128, 95%) (Fig1). More than half (75 (62%)) resided in rural areas. Patient records uniformly indicated a minimum 5-year history of asthma medication use. The majority of patients reported high compliance to asthma medications. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between urban and rural patients in terms of demographic characteristics and comorbidities, apart from higher hypertension prevalence (24% v 43%, p=0.036) and lower current smoking status (26% v 56%, p=0.030) in the rural group. Approximately 63% of those surveyed had at least one chronic disease. Interestingly, most patients, particularly those residing in urban areas, had their asthma diagnosed by a pulmonologist, whereas only 25% were diagnosed by a GP (7% in urban versus 36% in rural areas, p<0.001) (Table 2). Follow-up, where available, seems to have been undertaken mainly by GPs (49%), with a significant difference between rural and urban areas, as GPs had minimal role in follow-up care in urban compared to rural areas (22% v 65%, p<0.001). Also, rural patients tended to have at least one follow-up visit compared to urban patients (84% v 70%, p=0.061) (Table 2).

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of included patients in the study

| Characteristic | Variable |

Total population (N=121) mean±SD/n(%) |

Rural population (n=75) mean±SD/n(%) |

Urban population (n=46) mean±SD/n(%) |

p-value mean±SD/n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Gender, female | 81 (67) | 49 (65) | 32 (70) | 0.631 |

| Age, years |

50±20 |

53±20 | 46±18 | 0.060 | |

| Age ≤60 years |

85 (70) |

50 (67) | 35 (76) | 0.271 | |

| Age >60 years |

36 (30) |

25 (33) | 11 (24) | ||

| Smoking status | Current | 42 (35) | 20 (26) | 26 (56) | |

| Never/former smoker |

79 (65) |

55 (74) | 20 (44) | 0.03 | |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 43 (36) | 32 (43) | 11 (24) | 0.036 |

| Cardiovascular disease |

14 (12) |

10 (13) | 4 (9) | 0.439 | |

| Type 2 diabetes |

13 (11) |

11 (15) | 2 (4) | 0.070 | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

16 (13) |

10 (13) | 6 (13) | 0.964 | |

| Hyperlipidemia |

38 (31) |

28 (37) | 10 (22) | 0.073 | |

| Malignancy |

1 (1) |

1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.432 | |

| Atopic dermatitis |

16 (13) |

9 (12) | 7 (15) | 0.612 | |

| Osteoporosis |

19 (16) |

13 (17) | 6 (13) | 0.529 | |

| Number of comorbidities | 0 or 1 | 76 (63) | 43 (57) | 33 (72) | 0.111 |

| ≥2 |

45 (37) |

32 (43) | 13 (28) |

SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1: Flowchart of patients included in the study.

Figure 1: Flowchart of patients included in the study.

Asthma and allergic rhinitis control

The scores of the three questionnaires are displayed in Table 2. Regarding internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83 for CARAT, 0.90 for the ACQ-6 and 0.84 for the ACT. All the correlation coefficients between subscales of the questionnaires were statistically significant with p<0.001. CARAT score was significantly correlated with ACT (r=0.6970, p<0.001) and ACQ-6 scores (r=−0.7284, p<0.001), even after adjustments for confounders. The ACQ-6 and ACT scores were also highly correlated (r=−0.8751, p<0.001).

Participants had a mean CARAT score of 18, and 88% of them were classified as having not-well-controlled asthma and allergic rhinitis. The CARAT score was comparable between the rural and urban groups, with a slight trend towards better control in the rural group, although this difference was not statistically significant (15% v 9%, p=0.333). Adequate and partially controlled asthma according to ACQ-6 scores was noted in 33% of participants, with a tendency of better clinical control in the rural group (38% v 26%, p=0.144). Sixty-six participants (54%) were classified as having not-well-controlled asthma based on the ACT score, with no significant differences between the two groups (55% v 54%, p=0.973).

After adjusting for age, gender, comorbidities and smoking status, it was observed that improvements in all questionnaire scores, which indicate better control, were linked to residing in rural areas. More specifically, not only the total score of the CARAT (β (95%CI) 2.1 (0.1–4.0), p=0.039) but also CARAT asthma score (β (95%CI) 1.2 (0.1–2.3), p=0.041), and ACT asthma score (β (95%CI) 1.1 (0.1–2.3), p=0.040) (higher scores indicating better control) displayed a positive association with living in a rural area. ACQ-6 asthma score (lower scores indicating better control) (β (95%CI) –2.7 (–4.7–−0.6), p=0.010) also showed an inverse association with rural area of residence.

The results from the logistic regression analysis (Table 3) showed that females (odds ratio (OR)=4.1, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.8–19.9, p=0.043), and patients living in rural areas (OR=3.8, 95%CI 1.4–10.5, p=0.010) were more likely to report well-controlled asthma and allergic rhinitis based on CARAT score (>24). Follow-up by a pulmonologist was also associated with better asthma control based on the scores of all questionnaires used: CARAT (OR=6.3, 95%CI 1.2–33.9, p=0.031), ACT (OR=4.5, 95%CI 1.1–18.1, p=0.034) and ACQ-6 (OR=4.5, 95%CI 1.1–18.1, p=0.034).

Table 2: Asthma diagnosis, follow-up and questionnaire scores of patients

| Characteristic | Variable |

Total population (N=121) mean±SD/n(%) |

Rural population (n=75) mean±SD/n(%) |

Urban population (n=46) mean±SD/n(%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma diagnosis | GP | 30 (25) | 27 (36) | 3 (7) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonologist |

88 (73) |

48 (64) | 40 (87) | ||

| Other |

3 (3) |

0 (0) | 3 (7) | ||

| Follow-up | None | 26 (22) | 12 (16) | 14 (30) | <0.001 |

| GP |

59 (49) |

49 (65) | 10 (22) | ||

| Pulmonologist |

36 (30) |

14 (19) | 22 (48) | ||

| Any follow-up (≥1) | 95 (78) | 63 (84) | 32 (70) | 0.061 | |

| Regular follow-up | 67 (55) | 41 (55) | 26 (57) | 0.842 | |

| CARAT | Allergic rhinitis | 6.1±3.0 | 6.05±3.0 | 6.2±3.1 | 0.833 |

| Asthma |

12.2±3.2 |

12.4±3.4 | 11.8±3.0 | 0.291 | |

| Total score |

18.3±4.9 |

18.5±5.1 | 18.0±5.1 | 0.572 | |

| Controlled (>24) |

15 (12) |

11 (15) | 4 (9) | 0.333 | |

| Not well controlled (≤24) |

106 (88) |

64 (85) | 42 (91) | ||

| ACQ-6 | 1.8±0.9 | 1.7±0.9 | 1.9±0.8 | 0.213 | |

|

Adequate asthma control (≤0.75) |

19 (16) |

11 (15) | 8 (17) | 0.144 | |

|

Partially controlled (0.75 |

21 (17) |

17 (23) | 4 (9) | ||

| Not well controlled (≥1.5) |

81 (67) |

47 (63) | 34 (74) | ||

| ACT | 18.8 ± 3.2 | 18.9±3.3 | 18.6±3.1 | 0.597 | |

| Well controlled (>19) |

55 (46) |

34 (45) | 21 (46) | 0.973 | |

| Not well controlled (≤19) |

66 (54) |

41 (55) | 25 (54) |

ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire. ACT, Asthma Control Test. CARAT, Control of Allergic Rhinitis/Asthma Test. SD, standard deviation.

Table 3: Multivariable logistic regression analysis for good asthma control (dichotomous scales)

| Characteristic | Variable | Good control, CARAT total score >24 | Good control, ACT score >19 | Good control, average ACQ score ≤0.75 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OR (95%CI) |

p-value |

OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value | ||

| Demographics | Female v male | 4.1 (1.8–19.9) | 0.043 | 2.4 (0.7–8.6) | 0.183 | 1.2 (0.6–2.7) | 0.607 |

| Age>60 |

1.3 (0.3–6.4) |

0.750 | 0.5 (0.1–2.2) | 0.326 | 1.2 (0.4–3.8) | 0.773 | |

| Current smoking v never/former smoking |

1.6 (0.7–3.8) |

0.267 | 0.7 (0.2–2.6) | 0.578 | 1.6 (0.4–7.5) | 0.522 | |

| Area of residence | Rural vs urban | 3.8 (1.4–10.5) | 0.010 | 1.4 (0.4–4.6) | 0.572 | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 0.550 |

| Medications | INS | 3.0 (0.8–12.1) | 0.114 | 3.6 (1.1–12.1) | 0.035 | 1.9 (0.7–5.4) | 0.202 |

| Antihistamines |

0.4 (0.1–2.0) |

0.266 | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.534 | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 0.338 | |

| LTRA |

0.4 (0.1–1.9) |

0.236 | 0.8 (0.3–0.8) | 0.554 | 1.5 (0.5–4.5) | 0.479 | |

| ICS + LABA |

0.4 (0.1–1.2) |

0.097 | 1.0 (0.5–2.3) | 0.928 | 0.6 (0.2–1.6) | 0.272 | |

| SABA |

1.1 (0.3–3.7) |

0.896 | 0.2 (0.0–1.1) | 0.066 | 0.2 (0.0–1.1) | 0.066 | |

| OCS |

– |

– | 0.2 (0.0–1.7) | 0.143 | 0.1 (0.0–1.3) | 0.080 | |

| ICS + INS |

0.9 (0.3–3.1) |

0.840 | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.146 | 1.7 (0.6–4.6) | 0.324 | |

| Comorbidities | ≥1 | 0.9 (0.4–2.3) | 0.857 | 1.7 (0.6–4.6) | 0.265 | 0.5 (0.2–1.9) | 0.326 |

| ≥2 |

– |

– | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 0.094 | 0.4 (0.1–1.3) | 0.129 | |

| Diagnosis by pulmonologist v GP/other |

|

0.8 (0.2–3.0) | 0.779 | 2.3 (0.9–6.0) | 0.081 | 0.8 (0.3–2.6) | 0.775 |

| Follow-up by pulmonologist v GP/other |

|

6.3 (1.2–33.9) | 0.031 | 4.5 (1.1–18.1) | 0.034 | 4.5 (1.1–18.1) | 0.034 |

ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire. ACT, Asthma Control Test. CARAT, Control of Allergic Rhinitis/Asthma Test. CI, confidence interval. ICS, inhaled corticosteroid. INS, intranasal steroid. LABA, long-acting beta-agonist. LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist. LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist. OCS, oral corticosteroid. OR, odds ratio. SABA, short-acting beta-agonist.

Impact of treatment on asthma and allergic rhinitis control level

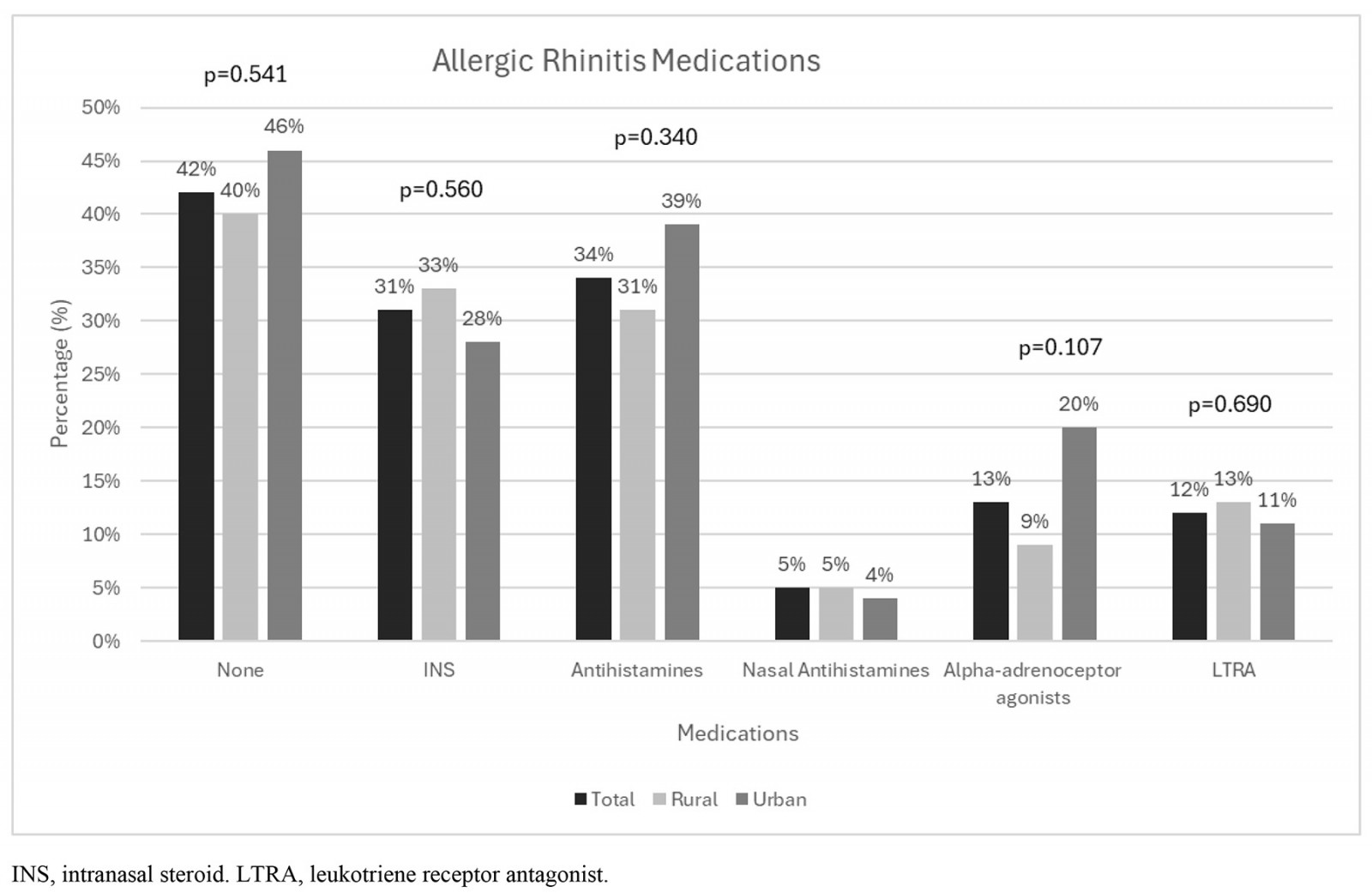

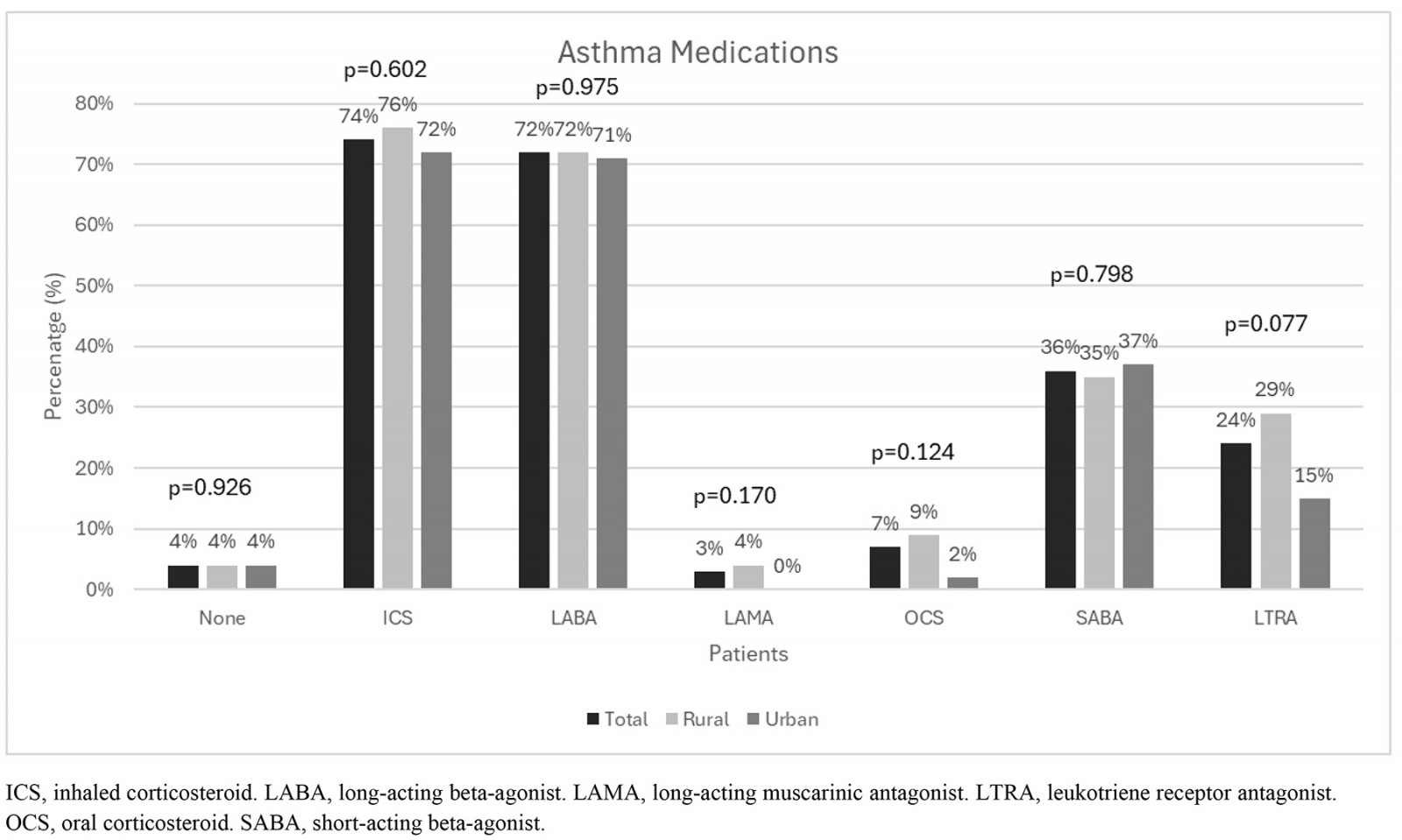

Details of medical treatment for asthma and allergic rhinitis of all patients and according to area of residence are presented in Figure 2. Within the population, 58% of patients were receiving symptomatic drugs for allergic rhinitis, such as antihistamines (34%), intranasal steroids (31%), nasal antihistamines (5%), alpha-adrenoceptor agonists (13%), and 46% reporting frequent use of two or more allergic rhinitis medications. A considerable proportion of patients reported no systematic treatment for allergic rhinitis (42%). When asked about asthma therapy, 74% of patients reported inhaled corticosteroid use (69% systemic use) and 72% inhaled corticosteroids in combination with long-acting beta-agonists. An increased need of short-acting beta-agonists as rescue therapy was noted in as many as 36% of the responders, without significant difference between the rural and urban groups. Eight (7%) patients reported frequent use of oral corticosteroids for asthma exacerbation treatment, in favor of rural patients (11 v 2%, p=0.124). It should be also noted that the utilization of leukotriene receptor antagonists was reported by only 15% of urban patients, while the percentage was higher at 29% for rural patients (p=0.077). Nevertheless, no statistically significant difference was noted in medication usage between the rural and urban groups.

After adjustment for confounders, it was noted that intranasal steroid use was positively associated with CARAT allergic rhinitis score (higher scores indicating better control) (β (95%CI) 1.4 (0.2, 2.6), p=0.011), and oral corticosteroid use was inversely associated with CARAT total score (β (95%CI) –2.2 (–4.4–−0.0), p=0.045). Supplementary table S1 and Table 3 present the findings from the univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis, respectively. The results from the multivariable logistic regression analysis show that patients reporting intranasal steroid use (OR=3.6, 95%CI 1.1–121, p=0.035) were more likely to have well-controlled asthma based on ACT score. Analysis also indicated a trend towards significance for the association between short-acting beta-agonists and not-well-controlled asthma based on ACT (score≤19) (OR=5, 95%CI 0.09–10, p=0.066) and partially and not-well-controlled asthma based on ACQ-6 (score>0.75) (OR=5, 95%CI 0.09–10, p=0.066). A trend was also noted for the association between frequent oral corticosteroid use (OR=10, 95%CI 0.8–10, p=0.080) and not-well-controlled asthma based on ACT score.

Figure 2: Distribution of all allergic rhinitis (A) and asthma medications (B) according to area of residence.

Figure 2: Distribution of all allergic rhinitis (A) and asthma medications (B) according to area of residence.

Discussion

Our study aimed to assess the level of asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis control, identify potential associated predictors and explore the differences in control and treatment between patients residing in urban and rural areas of Greece. We found that a significant proportion of asthma and allergic rhinitis patients self-reported not achieving well-controlled asthma and allergic rhinitis. No variation in medication usage was observed between the rural and urban groups. Being female, living in rural areas, regular use of intranasal steroids and follow-up by a pulmonologist was significantly associated with better asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis control status. On the other hand, patients with frequent oral corticosteroid and short-acting beta-agonist use were less likely to have self-reported well-controlled asthma.

Asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis control in urban versus rural areas

Making a diagnosis of asthma can be challenging, especially in rural primary care environments38. Although in our study asthma diagnosis was made mainly by pulmonologists, a considerable proportion of patients received their diagnoses from GPs in rural areas. Furthermore, our study showed a positive association between follow-up care from pulmonologists and achieving better control over asthma and allergic rhinitis. This result is not unexpected, as it is common for pulmonologists in Greece to play the primary role in managing asthma patients in Greece, followed by GPs and internists39. Taking into account the lack of medical equipment, working conditions and the higher burden of work in rural areas40,41, it is reasonable to assume that GPs serving in rural areas may face additional challenges in managing patients with asthma and allergic rhinitis than their counterparts in urban areas. Therefore, it is crucial for GPs to enhance their knowledge and skills in the management of asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis and to explore strategies to improve the implementation of management guidelines in their practice. Rural GPs can play a crucial role in effectively controlling asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis due to their close and long-term relationships with patients, compared to anonymity – which is more prominent among urban GPs42,43. This is also the case in Greece, in which a striking feature in primary care is the communication between GPs and patients, contributing potentially to better asthma and allergic rhinitis control44.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in a real-world setting comparing asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis control and medical treatment between urban and rural patients in Greece. Two asthma control measurement tools were applied to assess asthma control levels, and one for asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis. The ACT and the ACQ-6 are the most often applied instruments in clinical practice. Previous research has found strong and consistent correlations between improvement in ACT score and improvement in ACQ score45, a finding that is also evident in our study. The overall mean asthma control level based on ACT was 19±4, indicating not-well-controlled asthma (well-controlled score >19), which is consistent with a previous study conducted by telephone in Greece46, as well as with findings from other studies conducted in primary care settings in the UK47, Singapore48 and Portugal49. Furthermore, 54% of patients were classified as having not-well-controlled asthma, which is comparable50, higher51-53 or even lower54 than in other studies using the ACT questionnaire and conducted in primary care settings. The overall mean asthma control level based on the ACQ-6 was 1.8±0.9 (not-well-controlled score ≥1.5), indicating not-well-controlled asthma, which is worse compared to a previous study conducted in Greek primary care settings55 and better compared to previous studies conducted in primary care patients with asthma30,56,57. Based on ACQ-6 score, 67% of patients were classified as having not-well-controlled asthma, which is higher than previously reported in primary care57-59. The variations in asthma control between rural and urban areas have not been extensively studied, with only limited research available60. In our study, the ACT scores did not show any variations between rural and urban areas, which supports the findings of a previous study60.

When evaluating asthma control, the clinical heterogeneity of asthma must be considered. It is well known that asthma is a heterogeneous disease that includes multiple phenotypes, the most common of which is allergic asthma combined with allergic rhinitis61. Importantly, allergic rhinitis is the most common comorbidity in patients with asthma and is associated with unfavorable outcomes, such as more frequent exacerbations and poor control of the disease62. This recognition has resulted in a combined approach for asthma and allergic rhinitis63. In our study, assessment of how asthma with comorbid allergic rhinitis is controlled was made with the CARAT questionnaire, the results of which could influence clinical decisions and patient understanding28. CARAT appears to have good discriminative performance, similar to other asthma control assessment tools, for asthma patients with and without allergic rhinitis59. Consequently, the use of the CARAT questionnaire is highly recommended as a combined tool for assessing control of asthma and allergic rhinitis at the same time14. The overall mean CARAT score in our study was 18±5 (not-well-controlled score ≤24), indicating not-well-controlled asthma and allergic rhinitis, which is worse compared to previous studies conducted in a mixed population (primary and secondary practices in an international multi-center study in Austria, France and Italy)14, in community pharmacies64 and primary care practices30 in the Netherlands. On the other hand, the score in our study was better than previous studies in primary care populations in Portugal49 and mixed populations in the Netherlands65. The majority of patients (88%) reported having not-well-controlled asthma, which is similar66,67 or higher compared to an earlier study in primary care49. While the CARAT score was similar in both the rural and urban groups, there was a slight inclination towards improved control in the rural group. However, this trend did not reach statistical significance due to the limited number of patients in each group.

Factors associated with asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis control

Based on the aforementioned findings, it was evident that a significant proportion of the participants had not achieved well-controlled asthma and allergic rhinitis. Therefore, identification of risk factors for poor asthma and allergic rhinitis control is an essential strategy for reducing the disease's negative health consequences as well as economic burden68. Our results have revealed that female gender was linked to better asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis control levels compared to males. The variation in asthma and allergic rhinitis control between genders may be due to differences in health behaviors, and exposure to triggers and long-term factors69. It appears that women perceive asthma symptoms as more troublesome than men, even when the severity of asthma and lung function (measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 second) are comparable70, and they are more likely than men to inform a healthcare professional about them71. Societal expectations that discourage men from speaking about their health symptoms may cause them to understate their symptoms and hesitate to seek asthma and allergic rhinitis care, ultimately leading to worse control of these conditions72. Furthermore, because of their gender roles and jobs, men may be exposed to different asthma and allergic rhinitis triggers or substances, which may affect control of their asthma with comorbid allergic rhinitis73.

Living in rural areas was significantly associated with good asthma and allergic rhinitis control status. Given that individuals residing in rural areas are exposed to fewer pro-inflammatory factors like car exhaust, industrial pollutants and processed foods20,21, it can be hypothesized that the rural population experience less severe respiratory symptoms and demonstrate improved management of asthma and allergic rhinitis compared to their urban counterparts74. Additionally, as previously stated, establishing an effective relationship between patients and healthcare providers is crucial. Especially in rural areas, GPs practicing for many years dedicate time to discuss patients' issues, encourage healthy behavior changes and collaborate on self-management approaches – potentially enhancing control of asthma and allergic rhinitis75. It is also important to highlight that there were no significant variations in medication usage between the rural and urban groups, implying that access to care and pharmacies is not limited in rural areas. This aspect may further contribute to better asthma control in these areas.

Importantly, regular usage of intranasal steroids was strongly linked to improved control of asthma with comorbid allergic rhinitis. This finding is not unexpected and aligns with the results from a previous systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials involving patients with both asthma and allergic rhinitis76. The analysis demonstrated that the use of intranasal corticosteroid medications resulted in improved asthma symptom scores. Additionally, the findings imply that applying intranasal steroids directly to the upper airway can effectively address symptoms specific to the lower airway and reduce the reliance on rescue medication76. This holds particular significance when considering that higher usage of rescue medications, specifically short-acting beta-agonists and oral corticosteroids, was linked to poorer control of asthma in our study. These findings are consistent with earlier studies, which indicate a link between increased short-acting beta-agonist48,77,78 and oral corticosteroid79 usage and not-well-controlled asthma. This is also true for individuals with severe asthma, where approximately 30% of patients need to take oral corticosteroids in order to achieve partial or complete symptom control80. As a result, patients often experience oral corticosteroid-related side effects such as type 2 diabetes, osteopenia/osteoporosis, digestive disorders, obesity, high blood pressure, cataracts and obstructive sleep apnea81,82. These conditions further contribute to the overall disease burden.

Clinical implications

Our findings are consistent with those of other international studies, and they also add to the limited body of literature regarding the management of asthma and allergic rhinitis by GPs in rural and urban Greek practices, and the relationships between comorbid allergic rhinitis and asthma control in a real-world setting. As the focus in asthma management has evolved to prioritize asthma control, the use of questionnaires for assessing asthma and allergic rhinitis symptom control has become increasingly important. In addition, addressing factors associated with asthma and allergic rhinitis control, and implementing personalized strategies and interventions, could potentially lead to improved management of asthma with comorbid allergic rhinitis.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study was that it was a real-life study that used well-validated tools to measure asthma and allergic rhinitis control. However, there are some limitations. First, based on asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis prevalence data in Greece44,83, a higher number of enrolled patients with asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis was expected. The reason for this could be that this study was started at the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in limited in-person visits, favoring shorter visits, and potentially small sample size. The COVID-19 pandemic substantially impacted asthma monitoring within primary care settings, particularly regarding patient understanding of the influence of asthma control on COVID-19 complication risk84. The involvement and education of GPs is therefore essential for improved asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis control, especially in the event of a future pandemic. Furthermore, our sample size was comparable to those in previous studies examining associations between asthma and allergic rhinitis and related outcomes. Despite these limitations, our findings are derived from patients drawn from primary care of Greece in which allergic rhinitis and asthma diagnoses were confirmed by a physician.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that asthma and allergic rhinitis control remains suboptimal in a large proportion of patients with asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis in primary care settings. Area of residence, female gender, follow-up by a pulmonologist and medication-related variables were significantly associated with asthma and allergic rhinitis control. It is essential to take these factors into account to optimize not only treatment, but also self-management behaviors, to achieve better asthma and allergic rhinitis outcomes. Further studies in larger populations are needed to confirm these results.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

Supplementary material is available on the live site https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/9570/#supplementary

You might also be interested in:

2015 - Post-mortem as preventative medicine in Papua New Guinea: a case in point

2015 - Occupational therapy: what does this look like practised in very remote Indigenous areas?