Introduction

The prevalence of violence against women continues to be a pervasive public health issue. Globally, one in three women have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) or sexual violence (SV) in their lifetime1. Advocates often signify these rates as an underestimation of the problem because IPV, SV, and gender-based violence (GBV) are not often reported to the authorities2,3. There is also evidence that suggests incidences of IPV, SV, and GBV are higher in rural, remote, and Northern (RRN) geographical areas4. The psychological, physical, and financial impacts of this violence is well documented, and studies have shown that individuals who experience this type of violence have negative health and mental health outcomes that can persist for years after the abuse occurred5. Therefore, determining the lived experience of individuals who are victims/survivors of IPV and SV is an important social issue. For this reason, a scoping review was conducted to explore existing literature on the experiences of IPV and SV victims/survivors from RRN regions. To conduct the scoping review, we began by identifying key terms and definitions including the concept and context6.

Concept: Intimate partner violence and sexual violence

Assessing the existing literature regarding IPV and SV was a difficult task, as the definitions of IPV, SV, and GBV often overlap. For instance, IPV and SV are both forms of GBV if they are directed at marginalized genders. IPV can include SV, and SV could be defined as IPV. Therefore, we used all three terms, along with commonly used terms, to identify all the relevant literature. Within the broader categories of GBV, IPV, and SV, there are also other common terms. IPV has also been referred to as domestic violence, partner abuse, wife battering, and dating violence in the literature7.

One of the key factors of IPV is that a previous or current intimate partner initiates the abuse, and can include acts of sexual coercion, rape, unwanted sexual contact, physical violence, stalking, and psychological aggression8,9. By comparison, SV is any attempted or completed sexual act that is unwanted by the victim/survivor10. Any person can perpetrate SV, and unlike IPV the victim/survivor does not need to know the perpetrator or have had a previous relationship with them. Examples of SV include coercion, stealthing, rape, attempted rape, and sexual assault. GBV is a more fulsome term, that encompasses all violence directed at individuals based on their gender, gender expression, gender identity, or perceived gender. GBV includes physical, psychological, sexual, technology-facilitated, economic, emotional, and societal violence11. Although distinct terminology, IPV, SV, and GBV are often tangled because of the similarities between the experiences of violence. For instance, the term ‘intimate partner sexual violence’ is used to describe SV that occurs within intimate partner relationships12,13.

Context: Rural, remote, and Northern

Those marginalized by gender, such as cisgender women, transgender, non-binary, and other gender-diverse individuals, are at a significantly higher risk of experiencing IPV in RRN areas compared to those in urban settings4,14. Women in RRN areas contend with more severe violence, and they are less likely to report or access the supports they require11,14. In 2022, it was determined that at least 42% of victims of femicide, the most harmful form of IPV and GBV, lived in rural or remote areas in Canada15. Additionally, this proportion increased by 27% in 2022 when compared to 2019, which shows the issue is amplifying15. In the US, it is difficult to ascertain the exact numbers of femicide due to a lack of codification and national surveillance; however, advocates have been calling for femicide to be classified and defined within the penal code to provide better statistics and trackable data16. Considering that at least 20% of the North American population lives in RRN areas, this increased risk of IPV and SV is problematic17.

RRN areas face unique challenges in addressing IPV and SV due to factors such as geographical isolation, a lack of services that support women with IPV and SV, social stigma, and a lack of understanding surrounding the complexities of IPV and SV from rural service providers18-21. Complicating the issue, the culture in RRN communities often deters individuals from seeking and obtaining services that will support them22. Heteronormative beliefs are perpetuated in rural areas, which conforms women to traditional gendered stereotypes23. Financial dependence, commitments to children, extended family, and pets all compound this typical narrative20,24, making it harder for women to leave to access assistance. A lack of appropriate and timely services increases the risk to victims/survivors and prolongs their trauma experiences if they do seek out justice, mental health, or physical health services25. Lastly, the close-knit communities, smaller population sizes, and isolation of RRN communities may require that the victim/survivor remain in regular contact with their perpetrator, increasing the trauma they experience20.

To prepare for the scoping review, the authors conducted a preliminary review of IPV and SV in RRN communities using Google Scholar. The quick review identified 17,300 results, showing a wealth of information on the topic. However, upon further review, it was found that the manuscripts focused on outlining the risk factors for this type of violence21,26, the experiences of service providers in RRN areas4,18,27, or they focused on quantitative studies from outside the targeted area28,29. There was limited literature focusing on the lived experience of these instances of violence in RRN populations4. Therefore, a comprehensive scoping review on the topic was warranted.

Methods

Arksey and O’Malley introduced the first methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews, which has since been reviewed and refined by other researchers30,31. This review followed the enhanced methodology outlined by Levac and colleagues, who maintained the original stages of the Arksey and O’Malley framework while offering greater guidance on the implementation30,31. The scoping review process adhered to the following five stages: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; and collating, summarizing, and reporting the findings30,31. The review utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines32. The protocol was registered with Open Science Framework following development of the study protocol and search strategy.

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

Due to the broad nature of the research question, a scoping review was selected as the method, allowing for synthesis of a wide range of information on this topic31. A scoping review was conducted to answer the question ‘What is available in the evidence regarding the lived experience of SV and IPV among those marginalized by gender in RRN areas in North America?’ The aim of the review was to identify evidence available regarding the experiences of SV and IPV in RRN areas, identify key characteristics and factors associated with SV and IPV in RRN areas, and identify and analyze current knowledge gaps.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

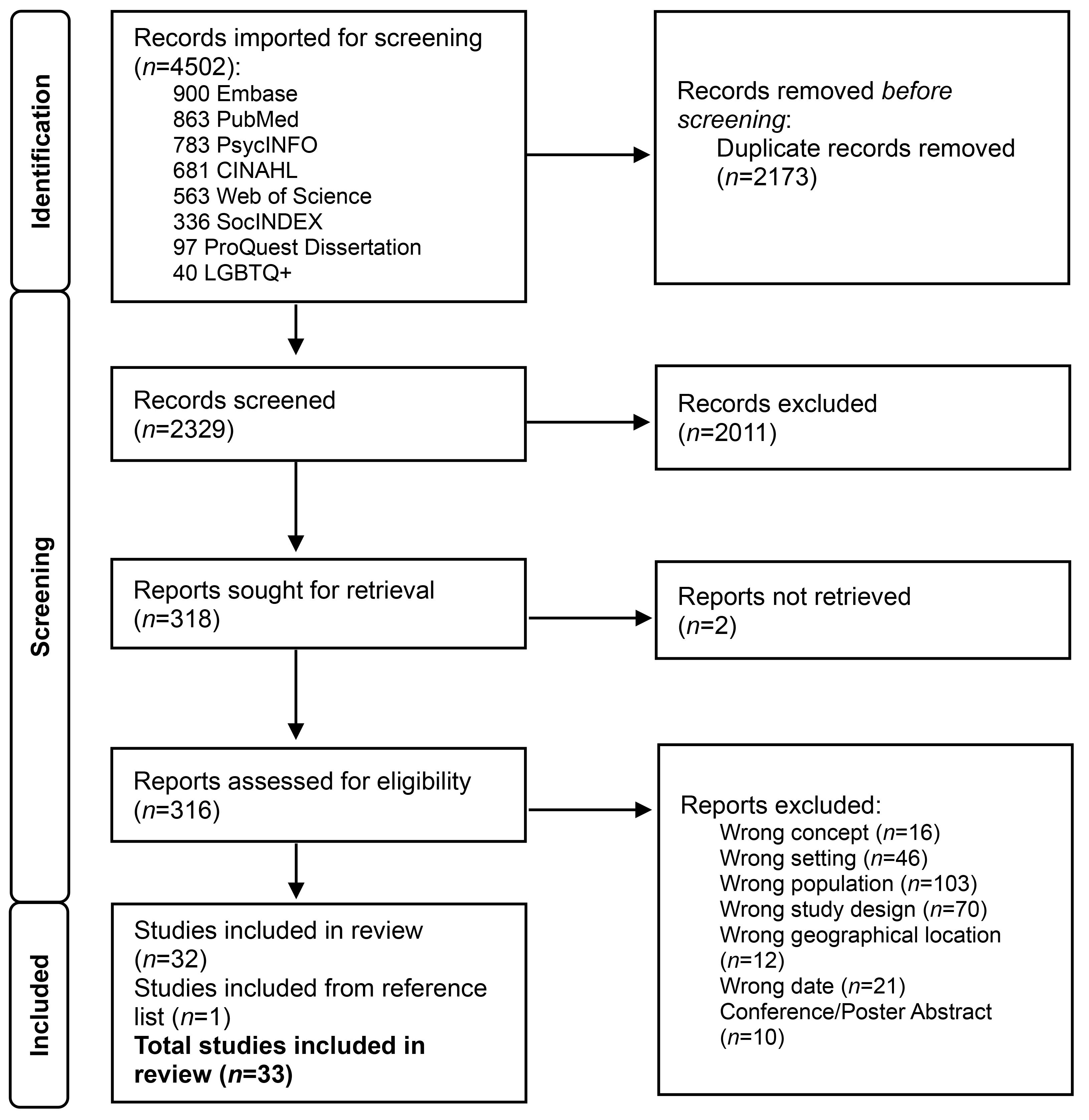

Initial search terms were identified to best reflect the three main concepts of this study: IPV, rural, and research methodologies to be included. These were searched and refined using Embase, PubMed (including Medline), APA PsycInfo, Web of Science, CINAHL, SocINDEX, ProQuest Dissertation and Theses Global, and LGBTQ+ Source. Next, subject headings, where available, were consulted to improve the search strings. After consultation with the research team, concept keywords were selected and combined using Boolean operators (‘AND’, ‘OR’), wildcards (‘*’), phrase searching, and proximity operators (‘W#’). Proximity searches were used instead of phrase searching to ensure a wider range of relevant results for concepts that might not be expressed as a phrase. Search strings were adjusted for each database to maximize its usefulness. Finally, the reference lists of all included studies were screened to identify additional articles that met the inclusion criteria. A librarian completed the searches in collaboration with other members of the review team. We initially searched for articles published from 2005 to October 2024. However, the publication range was narrowed to 2015 to March 2025 after screening over 60 articles that met the review criteria. The updated exclusion criterion is indicated as ‘wrong date’ in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig1). The search strategy utilized for CINAHL is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Search strategy for CINAHL

|

Population, concept, context |

(rural OR remote OR northern) AND (‘intimate partner violence’ OR partner W2 violence OR partner W2 abuse OR spous* W2 abuse OR sexual W2 violence OR Sexual W2 abuse OR domestic W2 violence OR domestic W2 abuse OR sex W2 offences OR rape OR stealthing OR Sexual W2 Coercion) |

|---|---|

|

Study design |

AND (qualitative W2 (research OR study OR studies OR method*) OR case W0 (study OR studies) OR ethnographic W1 (research OR study OR studies OR method*) OR ethnologic* W1 (research OR study OR studies) OR ethnonurs* W1 (research OR study OR studies) OR ethnonursing W1 (research OR study OR studies) OR ‘focus group*’ OR ‘grounded theory’ OR historical W0 (research OR study OR studies) OR interview* OR ‘lived experience*’ OR ‘life experience*’ OR ‘mixed method*’ OR multimethod W1 (study OR studies) OR ‘action research’ OR ‘participatory research’ OR phenomenolog* W1 (research OR study OR studies OR analysis) OR ‘phenomenology’ OR ‘document analysis’ OR Hermeneutics OR ‘Narrative analysis’ OR ‘Thematic analysis’ OR ‘participant observation’ OR ‘conversation analysis’). |

Stage 3: Study selection

The population for this review involved individuals marginalized by gender (women, transgender, and non-binary individuals) who were 18 years or older and who had lived experience of SV and/or IPV. This population was selected because SV and IPV impacts those marginalized by gender more than cisgender males18,33,34. The context of the study is RRN locations of developed countries in North America (US and Canada). Initially, the review considered other developed countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and the UK. However, as previously mentioned, due to the large number of included studies, a geographical filter was applied to limit the included articles to the US and Canada. The updated exclusion criterion is noted as ‘wrong geographical location’ in the PRISMA flowchart. Developed countries in North America were selected for the review as they are high-income countries, with predominantly English-speaking residents, similar colonial histories, comparable medical standards, democratic governance, and feminist movements that have countered and challenged gendered violence and are equivalent or comparable countries35,36. The reviewers accepted all definition and descriptions of RRN identified by authors for inclusion.

Given that the research question focused on lived experiences, the review incorporated qualitative and mixed-methods studies. Mixed-methods studies were included if the qualitative component was presented in the findings. In addition, reviews, dissertations, and theses that met the inclusion criteria were considered. If publications were derived from dissertation/theses data, the dissertation/theses were included for analysis, rather than the published articles, given the wealth of information included in these sources.

Covidence was used as the review software to standardize the review process (https://app.covidence.org/reviews/488006). To ensure reliability of the results, two researchers reviewed the data independently during all stages of the review, including title and abstract screening, full-text review, and data extraction. A third, independent team member resolved any discrepancies that occurred during the review. When the decision was unclear, the team engaged in discussions to reach a consensus. The search identified 4502 articles of which 2173 were identified as duplicate records. Therefore, 2329 articles were reviewed. Thirty-two studies were identified as meeting the inclusion criteria, and one additional article was located after reviewing the reference lists of the included studies. A total of 33 articles were included in the review (Fig1).

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart for identification of relevant studies.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart for identification of relevant studies.

Stage 4: Charting the data

Data from all 33 articles were charted using a data extraction framework developed by the research team based on JBI guidelines37,38. The framework was piloted by team members prior to finalizing. Data were extracted regarding the author, year of publication, method, data collection, recruitment strategy, conceptual framework, sample, type of violence, and setting. Definitions regarding the type of violence and RRN were also included. Two members of the research team independently completed the data extraction table. A third, independent team member compared and finalized the chart.

Stage 5: Collating, summarizing, and reporting the findings

A descriptive approach to analysis was utilized including doing frequency counts (percentages and proportions) of data extraction items30,31,39. In addition, a narrative summary was utilized to describe how the results relate to the reviews, objectives, and research question39.

Results

The described results refer to 33 manuscripts on the experiences of IPV, SV, and GBV of RRN women. Tables 2, 3, and 4 provide the demographics of the manuscripts, including the population, country of origin, and study design.

Table 2: Articles by population, country of origin, and study design for intimate partner violence (n=26)

|

Population |

Study design |

Country of origin |

Author and year |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Not specified (n=13) |

Qualitative |

US |

Bryant (2020)40; Riffe-Snyder (2017)41; Wimbush (2024)42; Mullany and Gubrium (2024)43; Ravi (2024)44; Roush and Kurth (2016)45 |

|

Canada |

Kohtala (2021)46; Wood et al (2024)47; Mantler et al (2022)48; Hovey and Scott (2019)49; Mantler and Wolfe (2017)50; Mantler et al (2024)51 |

||

|

Mixed methods |

US |

Bender (2015)52 |

|

|

Pre-natal, peri-natal, and mothers (n=5) |

Qualitative |

US |

|

|

Canada |

|||

|

Mixed methods |

US |

Bhandari et al (2015)57 |

|

|

Women aged ≥50 years (n=2) |

Qualitative |

US |

Roberto and McCann (2021)58 |

|

Canada |

Weeks et al (2016)59 |

||

|

Women who use substances (n=2) |

Qualitative |

US |

|

|

Indigenous women (n=2) |

Qualitative |

Canada |

|

|

Women in the LGBTIA+ community (n=1) |

Canada |

Soares (2020)64 |

|

|

Women who experience homelessness (n=1) |

Qualitative |

Canada |

Flynn et al (2023)23 |

Table 3: Articles by population, country of origin, and study design for gender-based violence (n=5)

|

Population |

Study design |

Country of origin |

Author and year |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Not specified (n=2) |

Qualitative |

US |

DeKeserdy and Hall-Sanchez (2017)65 |

|

Canada |

Yates et al (2023)66 |

||

|

Women with disabilities (n=3) |

Qualitative |

US |

Aguillard, Gemeinhardt et al (2022)67; Aguillard, Hughes, Gemeinhardt et al (2022)68; Aguillard Hughes, Schick et al (2022)69 |

Table 4: Articles by population, country of origin, and study design for sexual violence (n=2)

|

Population |

Study design |

Country of origin |

Author and year |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Not specified (n=1) |

Qualitative |

US |

Giroux (2017)70 |

|

Indigenous women (n=1) |

Qualitative |

US |

Braithwaite (2016)71 |

Country of origin and study design

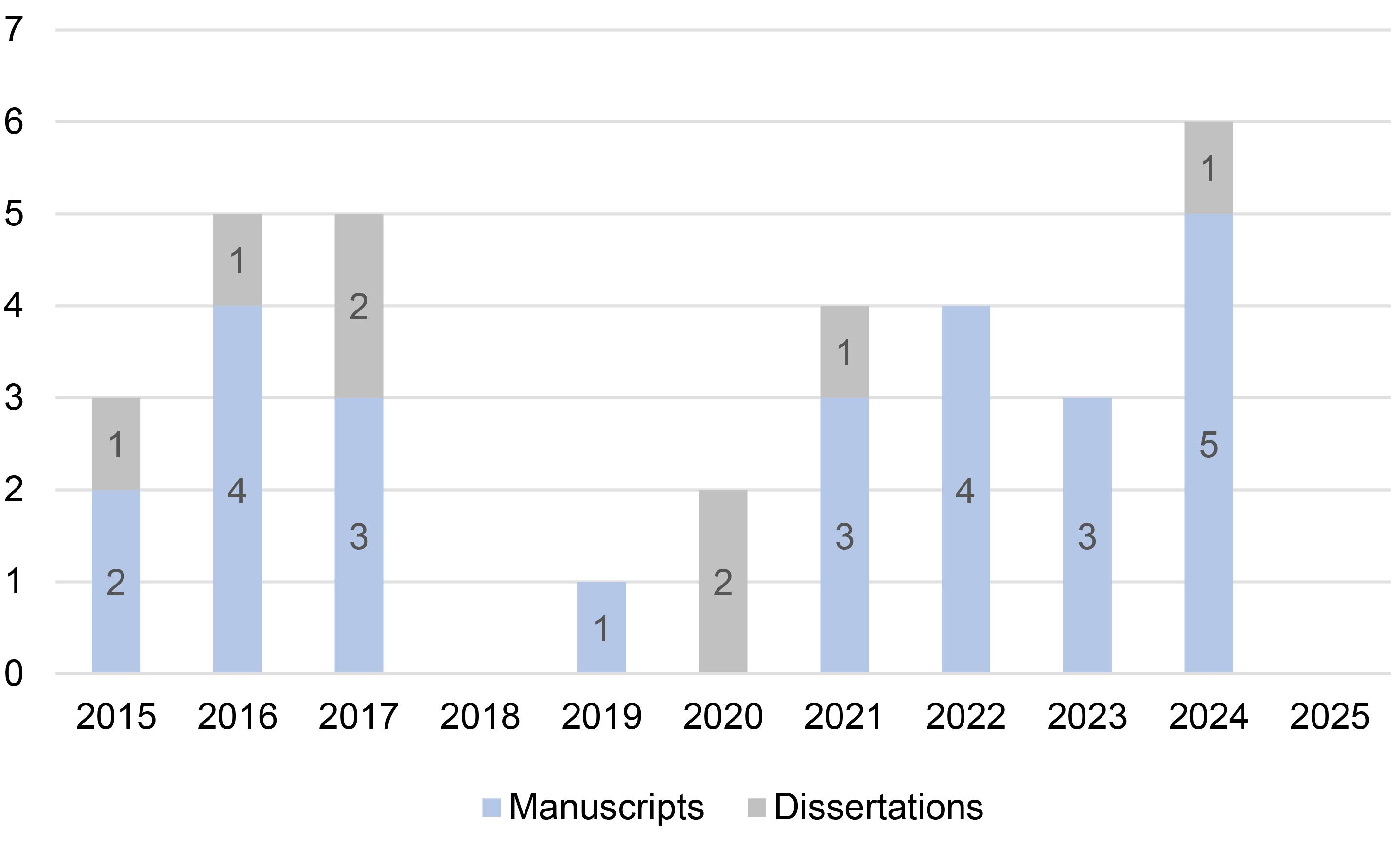

The articles included in the study were analyzed for country of origin and study design. Over half of the manuscripts included in this scoping review were written in the US (n=19, 58%) and 42% were from Canada (n=14). Given the nature of the research question and inclusion criteria, it is not surprising that most studies were qualitative (n=30, 91%), and the remainder utilized a mixed-methods approach (n=3, 9%). Nearly a quarter (n=8, 24%) were dissertations/theses40-42,46,52,64,70,71. Figure 2 outlines the type of publication, either articles or theses, and the date of publication.

In this review, most authors used a single source of data collection, primarily individual interviews (n=28, 85%), or less commonly focus groups (n=1, 3%). A smaller number of studies employed a variety of data collection strategies. These included combinations of interviews, observations, and field notes (n=2, 6%), as well as the use of photographs alongside interviews or focus groups (n=2, 6%).

In terms of recruitment strategies, over half of all manuscripts (n=17, 52%) described using a combination of approaches including asking service providers (eg women’s shelters and crisis center staff) to share recruitment information, along with community-based methods (eg community flyers, newspaper ads, and social media). Other studies relied exclusively on service providers (n=9, 27%) or community-based strategies (n=4, 12%) to distribute recruitment information. Three studies (9%) did not specify recruitment methods.

Figure 2: Publication type by year.

Figure 2: Publication type by year.

Conceptual frameworks

The most frequently reported conceptual framework to be utilized aligned with a feminist and/or intersectional lens (n=13, 39%). Of these, a feminist intersectional lens (n=5, 15%), feminist theory (n=4, 12%), and intersectionality (n=1, 3%) were utilized. A few other studies applied a feminist or intersectional theory in combination with other models (n=3, 9%). Kohtala reported utilizing multiple frameworks including intersectionality, a socioecological model, and an exposure reduction framework46. Wimbush utilized the superwoman schema (a feminist model) and adult resilience theory42, whereas Roberto and McCann reported using feminist theory and life course theory to guide their research58. Additionally, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, Ecological Systems Theory, family resilience theory, the interpretivist paradigm, space for action theory, standpoint theoretical perspective, story theory, strengths perspective, and symbolic interactionalism were each reported as being utilized in one study (n=1, 3%). Eleven studies (33%) did not include details regarding a conceptual framework. However, Aguillard and colleagues listed feminist disability theory as the conceptual framework in one of the three articles written about the Rural Safety and Resilience Study67-69.

Populations

As discussed, the articles reviewed were focused on the lived experiences of victims/survivors. Most focused on IPV (n=26, 79%), with only 15% on GBV (n=5), and 6% on SV (n=2). In addition, the definitions used to describe these experiences of violence varied. It is important to note the discrepancies, as many authors incorporated specific factors important to their population of study in the definition, a point that will be discussed later. Among all the studies, there were six distinct population groups, and the others were non-specified. The experiences of specific groups were represented as follows: 15% (n=5) of studies focused on prenatal, perinatal, and mothers; 9% (n=3) on women who experience disabilities; 9% (n=3) on Indigenous women; 6% (n=2) on women aged 50 and older; 6% (n=2) on women who use substances; 3% (n=1) on women in the LGBT2+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and two-spirit) community; and 3% (n=1) on women who experience homelessness. The remainder of the manuscripts, 48% (n=16), were non-specified; however, in studies that included unspecified populations, most participants were classified as white, heterosexual, and able-bodied as outlined in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Aims of studies reviewed

Experiences of victims/survivors

The purposes of the studies are listed in Table 5. Almost half of the studies (n=16, 49%) aimed to explore the experiences of victims/survivors of IPV, SV, and GBV, with experience being broadly defined. Some authors aimed to determine the experiences of IPV for individuals with diverse ethnicities, ages, gender identities, and sexualities41-43,47,57,58,62-64. Some of the manuscripts focused on specificity in the intersections between IPV and other forms of marginalization, while others examined experience across intersections. Other authors aimed to determine how different social situations, such as substance use60 impacted the experience of IPV. Lastly, IPV during pregnancy or motherhood53,55 was also considered. Survivor experiences of transportation coercion44, and homelessness23 were explored as well.

Regarding articles that featured experiences of GBV and SV, some looked at differing ethnicities, gender identities, and sexualities70,71. DeKeseredy and colleagues aimed to determine the experiences of GBV and SV among separated and divorced women65.

Table 5: Article purposes and demographic information for included studies

B, black. DV, domestic violence. GBV, gender-based violence. I, Indigenous. IPV, intimate partner violence. L, Latina. MR, multiracial. RRN, rural remote Northern (RRN). W, white. UL, unlisted

|

Author, year, country |

Context |

Aim/purpose |

Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Flynn et al (2023)23, Canada |

Rural: largely resource-based economies |

To determine how violence and homelessness overlap in the life courses of women from two regions of Quebec. |

n=22 woman including 1 transwoman; ages 23–61 years Ethnicity Majority W, 1 I |

|

Braithwaite (2016)71, US |

Rural: author specified |

To examine the problem of violence against Alaska Native women through the individual and collective voices of survivors. |

18 women; ages not specified Ethnicity Alaska Native |

|

Bryant (2020)40, US |

Rural: U.S. Census |

To explore psychosocial factors related to culture and community that contribute to or lead to successful outcomes for victims of IPV. |

12 women; ages 27–67 years Ethnicity 5 W 6 L 1 B |

|

Giroux (2017)70, US |

Rural: population of less than 50,000 |

To gain a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of female sexual assault trauma survivors from a rural setting and how providers can best support them. |

n=7 women; mean age 25.6 years Ethnicity 2 Alaska Native, 1 B, 4 W |

|

Riffe-Snyder (2017)41, US |

Rural: population of less than 2500 |

To explore past IPV as it occurs in Appalachian women residing in rural and non-urbanized areas. |

n=12 women; ages 32–57 years Ethnicity 1 B, 11 W |

|

Soares (2020)64, Canada |

Rural: population less than 30,000 and more than 30 minutes away from a community with a population of greater than 30,000 |

To explore the intersection of gender, sexuality, and rurality on a person’s experience of seeking health and social services following IPV. |

n=4 lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer women; mean age 26.75 years Ethnicity not specified |

|

Wimbush (2024)42, US |

Rural: an area with low population density |

To identify the coping strategies used by African American women who have survived DV living in rural areas. |

n=8 women; ages 25–69 years Ethnicity 8 B |

|

Bender (2015)52, US |

Rural: medically underserved area |

To understand experiences of IPV survivors concerning providers' responses, quality of care, and self-reported outcomes after disclosure. |

n=20 women; ages not specified Ethnicity 17 W, 1 MR, 1 B, 1 L |

|

Kohtala (2021)46, Canada |

RRN: Rural: population of less that 10,000; remote: areas that are not road accessible year-round; Northern- defined province and territories |

To explore the barriers in preventing safety planning among DV survivors in RRN regions and determine the best practices for supporting survivors. |

n=20 women; ages 20–70 years Ethnicity 7 I, 13 non-Indigenous |

|

Roberto and McCann (2021)58, US |

Rural: author specified |

To explore how women experienced IPV over the course of their lives and which resources were most helpful when they decided to end their most current relationship. |

n=10 older women; ages 54–70 years Ethnicity 10 W |

|

Aguillard, Gemeinhardt et al (2022)67, US |

Rural: author specified |

Rural safety and resilience study. Explore women with disabilities expectations, facilitators, and barriers to help seeking and securing safety. |

n=33 women; ages 19–72 years Ethnicity 24 W, 3 B, 2 L, 3 I, 1 MR |

|

Aguillard, Hughes, Gemeinhardt et al (2022)68, US |

Rural: author specified |

Rural safety and resilience study. Purpose is to highlight women with disabilities process of learning about and accessing services. |

n=33 women; ages 19–72 years Ethnicity 24 W, 3B, 2L, 3I, 1 MR |

|

Aguillard, Hughes, Schick et al (2022)69, US |

Rural: author specified |

Rural safety and resilience study. Purpose is to highlight women with disabilities process of learning about and accessing services. |

n=33 women; ages 19–72 years Ethnicity 24 W, 3B, 2L, 3I, 1 MR |

|

Bhandari et al (2015)57, US |

Urban and rural: author specified |

DV enhanced home visit study. To determine if perinatal IPV differs between African American women living in urban and rural environments. |

n=12 women (6 urban and 6 rural); ages not specified Ethnicity 12 B |

|

Brassard et al (2015)62, US |

Remote: author specified |

To gain a better understanding of the underlying causes of the overrepresentation of Aboriginal women among victims of DV. |

n=40 (22 Aboriginal residents and 18 service providers); age and ethnicity not further specified |

|

Glecia and Moffitt (2024)63, Canada |

RRN: Northern territories and northern parts of several provinces with a population less than 10,000 |

To understand Indigenous mothering within the contexts of Indigenous identities, IPV, and RRN places. |

n=16 women; ages 25–58 years Ethnicity 16 I |

|

Wood et al (2024)47, Canada |

Rural: outside a metropolitan area including small towns and villages, farms, First Nations, and northern communities |

To explore rural women’s experiences of IPV and coercive control and how conditions of rurality exacerbate these experiences. |

n=26 (13 women and 13 service providers); age and ethnicity not specified |

|

Mullany and Gubrium (2024)43, US |

Rural: author specified |

To examine the affordances of using composite narratives in presenting research findings from rural survivors of IPV. |

n=40 (32 women and 8 service providers); age not specified Ethnicity 94% W |

|

Copes et al (2021)60, US |

Rural: author specified |

To understand how people who use meth make sense of their lives. |

n=1 woman; age and ethnicity not specified |

|

Burnett et al (2016)53, US |

Rural: area outside of urban area with less than 2500 residents |

To explore lived experience of IPV during pregnancy and the first 2 postpartum years. |

10 women; ages 16–32 years Ethnicity 7 W, 3 B or L |

|

Nixon et al (2017)55, Canada |

Urban and Northern. Urban: approximately 700,000 people; Northern: small northern city with a population of 13,000 |

To examine how abused mothers protect their children from the harms of violence perpetrated against the mothers. |

n=18 women (9 urban and 9 Northern); mean age 34.3 years Ethnicity 14 I, 4 UL |

|

Ravi et al (2024)44, US |

Urban, sub-urban, rural: author specified |

To explore IPV survivors’ experiences with transportation coercion. |

n=20 women (7 urban, 8 sub-urban, and 5 rural); mean age 28 years Ethnicity 9 W, 8 B, 1 L, 1 MR |

|

DeKeserdy and Hall-Sanchez (2017)65, US |

Rural: author specified |

To use a talk-back method with 12 new participants, to reflect on previous study. |

n=55 women; age and ethnicity not specified |

|

Bacchus et al (2016)54, US |

Urban and rural: author specified |

DV enhanced home visit study. To explore experiences of being screened for IPV during perinatal home visits. |

n=26 women; ages 16–35 years Ethnicity 12 W, 8 B, 4 MR, 2 UL |

|

Mantler et al (2022)48, Canada |

Rural: populations less than 30,000 |

To explore the intersection of women’s experiences of rural health care within the context of IPV. |

n=8 women; ages 21–64 years Ethnicity 2 I, 6 UL |

|

Stone et al (2021)61, US |

Rural: author specified |

To explore barriers to substance use treatment for women who experience IPV and opioid use in rural Vermont. |

n=33 (32 women and 1 transgender/gender non-binary/gender queer); mean age 35 years Ethnicity majority W |

|

Roush and Kurth (2016)45, US |

Rural: population less than 50,000 |

To understand the lived experience of IPV for women living in a rural setting to inform efforts to provide effective care, support, and resources. |

n=12 women; mean age 49 years Ethnicity 12 W |

|

Weeks et al (2016)59, Canada |

Rural: living some distance to a major urban center |

To explore the resources that rural women in midlife and older use to leave abusive partners. |

n=8 women; ages 50–74 years Ethnicity 8 W |

|

Hovey and Scott (2019)49, Canada |

Rural: several small towns with no public transportation linking the communities |

To explore how women who have accessed a women’s shelter experience harm reduction approaches. |

n=25 women; mean age 41.5 years Ethnicity not specified |

|

Mantler and Wolfe (2017)50, Canada |

Rural: population of 20,335 |

To explore changes to a rural Ontario women’s shelter and how the shelter has adapted to address the changes. |

n=10 (4 women and 6 service providers); ages 15–64 years Ethnicity not specified |

|

Jackson et al (2024)56, Canada |

Rural: author specified |

To explore the role of resilience in the context of mothers who have experienced IPV in rural settings. |

n=18 (6 women and 12 service providers); women ages 36–57 years Ethnicity not specified |

|

Mantler et al (2024)51, Canada |

Rural: populations ranging from 2000 to 42,000 |

To explore how rural women experiencing IPV cultivate resilience and the ability to survive and thrive. |

n=36 (14 women and 12 service providers); ages 18–57. years Ethnicity not specified |

|

Yates et al (2023)66, Canada |

Rural: populations ranging from 2000 to 42,000 |

To fill this gap by exploring how resilience is influenced by economic abuse in rural Ontario in the context of GBV. |

n=36 (14 women and 12 service providers); ages 18–57 years Ethnicity not specified |

Experiences with external supports and services

Several studies explored victims/survivors’ experiences with external support (n=13, 39%). The most common external support was formal support, which included health services, substance use treatment, counselling, and mental health supports for IPV victims/survivors45,48,52,54,61 and GBV victims/survivors67-69. Researchers explored the experiences of victims/survivors with informal or community supports when impacted by IPV46,59. Authors aimed to determine the experiences of IPV victims/survivors with a variety of other services, including shelters49,50, and community culture or readiness more broadly40.

Identifying internal strength

The remaining publications considered the victims/survivors’ internal strengths (n=4, 12%). Determining IPV victims/survivors’ resilience51,56 and coping42 were included in the aims of these articles. When considering internal strengths, one manuscript focused on resilience of GBV victims/survivors66.

Definition of rural, remote and Northern

As mentioned above, for articles to be included in this scoping review the authors needed to indicate that the research was conducted in RRN areas. We categorized RRN based on how each auther defined it. Studies that indicated rural participants or a rural geographical setting were included. There were inconsistencies in how authors defined RRN and only 58% (n=19) of authors provided a definition. Terms used to describe rural communities included areas with a low population density42, outside of urban centers47,59. Descriptions such as resource-based economies23, and medically underserviced areas52 were also used. The definition used most frequently among authors was an environment that had a population of less than 30,000 people (n=3, 9%)48,50,64 and populations less than 50,000 people based on the non-metropolitan counter from the US Census (n=3, 9%)40,45,70. Approximately 6% of articles described ‘rural’ as being less than 2500 people (n=2)41,53 or as less than 10,000 people (n=2)46,63. In addition, one author described ‘rural’ as describing areas with populations ranging from 2000 to 42,000 (n=1, 3%)66. The authors who discussed remote areas included areas that were inaccessible by public transportation46,49. When the term ‘Northern’ was used, it was defined to include all three of the Canadian Northern Territories, as well as the areas defined as Northern by individual provinces46, and populations less than 13,00055.

Concepts of intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and gender-based violence

The articles reviewed focused on IPV (n=26, 79%), GBV (n=5, 15%), and SV (n=2, 6%). For this review, we used the labels indicated by the authors to help identify and categorize the studies. Definitions changed depending on the perpetrator, and the acts of violence included in the definitions.

Intimate partner violence

Of the articles that focused on IPV, 38% of the authors did not provide a definition for IPV23,43,44,49,53,55,59-62. WHO’s definition of IPV was a common definition used by authors40,41,54. This definition indicates that IPV includes any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes, physical, psychological, or sexual harm9. Roberto and McCann added neglect and financial abuse to their definition of IPV in the context of older adult women58. Others defined violence in the same context as the WHO definition but provided more detail on what defined an intimate partner, including current and former dates, boyfriends, husbands, and cohabitating partners46,57. Other authors added an element of coercive control to the definition of IPV42,48,50,51,56,63.

Gender-based violence

Some of the authors chose to use the term GBV, rather than IPV or SV. For three authors, this definition was used to account for all forms of violence in all romantic and familial relationships67-69. DeKeseredy and Hall-Sanchez defined GBV broadly to include physical, sexual, psychological, financial, economic blackmail, and material forms of violence, withholding of a woman’s earned wages, and harm to possessions and animals65. Yates and colleagues used the term GBV to recognize the specifically gendered and coercive, controlling nature of all forms of violence, meant to reinforce subordination among victims66.

Sexual violence

The remaining two articles used variations of the term SV to describe the violence experienced by victims/survivors. Rape, sexual assault, sexual abuse, and IPV were the terms used to describe SV70. Braithwaite used broad terminology to describe SV and did not provide a definition for their terms71.

Factors associated with intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and gender-based violence

Unique contextual factors influenced experiences of IPV, SV, and GBV in RRN areas. The most common barrier reported involved socioeconomic conditions, as 70% of studies indicated that financial difficulties and housing insecurity limited individuals’ ability to access services or leave abusive relationships23,40,41,43,45,47,48,50-56,58-60,62,65,66,69,71. Similarly, over half of the studies (55%) found that geographic isolation and inadequate transportation created barriers to accessing support and escaping abusive relationships41,44-47,51-53,55,59,61,62,65-69,71. Privacy concerns, combined with fear, stigma, and shame, often discouraged individuals from disclosing abuse and/or contacting law enforcement in 61% of studies23,41-43,45-47,51-54,59-62,64,68-70. Traditional gender norms and patriarchal rural culture were described in 48% of studies as factors that normalize IPV and contribute to women’s reluctance to seek help23,41,43,45-47,51-53,55,60,62,63,65,66,68.

In addition, service-related limitations, identified in 67% of studies, included a lack of specialized, trauma-informed, and culturally sensitive supports, along with insufficient provider expertise and screening related to IPV, SV, and GBV23,40,42,46-52,54,55,58,59,61-64,67-69,71. Only four studies (12%) reported a lack of awareness or knowledge of available resources and services in RRN areas40,52,54,59. Despite the barriers encountered, positive interactions with service providers were associated with healing and recovery. Forty-two percent of studies reported that knowledgeable, empathetic, trauma-informed, culturally sensitive, and non-judgmental provider responses fostered improved outcomes46,48-52,54,56,63,64,67-71. Additionally, across the literature, characteristics of resilience and internal strengths were prevalent among the victim/survivor participants23,40-56,58-71.

Discussion

The authors conducted an in-depth scoping review of IPV, SV and GBV in RRN areas of the US and Canada. Overall, we determined that most manuscripts published on IPV and SV in RRN areas focused on IPV. A paucity of literature depicting non-partner sexual violence or specifically addressing IPV existed. Furthermore, the experiences of transgender, non-binary, and other gender-diverse individuals were under-represented. Due to the overwhelming statistics associated with SV in RRN areas1, there is a need for further research examining the lived experiences of SV within this context. Although many SV victims/survivors have indicated their perpetrators are acquaintances8, this does not mean that they consider them to be intimate partners72. For instance, in over half of the reported sexual assaults in Canada, the perpetrator was identified as an acquaintance, neighbor, or friend73. By limiting the experiences by using language that includes intimate partnership, this may exclude the voices of individuals who are violated by someone they know but with whom they are not in an intimate relationship.

Throughout the scoping review, we found discrepancies in the definition of the terms. For instance, IPV was referred to as domestic violence and wife battering. When a definition was provided, it was most often consistent with the definition provided by WHO9,74. Other authors expanded the WHO definition to include concepts important to the population of study. As an example, Roberto and McCann emphasized neglect and financial abuse in their definitions of IPV in their study with older women58. This is consistent with other literature that emphasizes an increased reliance on partners for financial and health supports as women age75.

Like the definitions provided by authors for IPV, the definitions in articles that focused on SV also differed. For those that did provide a definition, whether as SV or sexual assault, it included a detailed description of numerous forms of unwanted sexual activities. This inclusive definition is consistent with those of other authors in the field of SV that emphasize the importance of honoring and recognizing all forms of unwanted sexual activity76. By recognizing all forms of SV, we minimize the opportunity for SV to be dichotomized by severity and criminality, which influences how individuals access support and understand their own experiences77,78.

Recruitment efforts typically employed a variety of strategies such as recruiting through services such as shelters as well as community-based approaches. Although successful, using services has a potential to bias the results to those that have already recognized the violence against them and have accessed services. This could also provide rationale regarding why most of the articles provide details on IPV, as SV victims/survivors might not access typical shelters for IPV victims/survivors72. Other authors suggest ways that research can be disseminated more effectively in RRN areas, including local newspapers, radio broadcasts, social media, podcasts, and sharing with local organizations; we encourage these methods to also be used in study recruitment79. Researchers need to be aware of and plan for these methods of recruitment, with the understanding that there might be an associated financial cost.

The findings of the scoping review provide insights into RRN realities. Consistent with studies focused on suicide and mental health, there continue to be barriers to attain service in these areas. As highlighted in the findings in this scoping review and strengthened by other studies, RRN environments have unique challenges such as reinforced gender stereotypes, confidentiality concerns, and a lack of accessible services80-82. Complicating the issue, in RRN areas there is limited availability for services that support IPV and SV victims/survivors25. Concentrating on solutions for the lack of services is the next step for researchers and public health officials. Additionally, determining ways to make existing services safer for victims/survivors by emphasizing the importance of trauma-informed and culturally safe responses to disclosure is imperative.

Interestingly, the findings of the scoping review also show a paucity of information that focuses on the IPV and SV experiences of North American Indigenous women and two-spirit individuals. In the scoping review, very few manuscripts (n=3, 9%) focused on the experiences of Indigenous Peoples. This is surprising, as Indigenous women have higher rates of IPV, SV, and femicide compared to non-Indigenous women in North America83,84. The complexities of colonization, disruptions in power structures, racism, discrimination, and legacies of trauma on Indigenous women that influence the violence rates within that population are beyond the scope of this review85. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that there is a deficit in knowledge regarding RRN Indigenous women’s experiences with SV and IPV. More research needs to be done to learn about their experiences for targeted interventions.

Research gaps and recommendations

From this scoping review, we were able to determine that definitions of IPV, SV, GBV, and RRN differ in the literature. Trying to find consistency among scholars is not necessary; rather, we encourage authors and researchers to ensure that they define the parameters of the research study to ensure clarity in analysis, and when comparing studies. This will assist individuals who are reviewing literature to have a clear understanding of the parameters of inclusion criteria for the study. Another recommendation is for researchers conducting studies in RRN areas to expand their methods of recruitment. By using more public forms of recruitment, there may be an opportunity to interact and engage with those who have not yet received services for their IPV, SV or GBV. Lastly, there is a need for further research on SV as there is a lack of information that specifically focuses on SV in RRN areas.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that this scoping review had limitations. Focusing on the lived experience of IPV and SV in RRN areas was difficult due to discrepancies in languages of the terms. Although a thorough review of the available literature was conducted, the discrepancy in terms may have resulted in missed manuscripts. Additionally, there were eight dissertations/theses in this review. To avoid duplication, we kept only the dissertation/thesis if there was a manuscript based on the same study; however, this may have resulted in missed information. Lastly, as this was a scoping review and not a systematic review, we were able to identify the gaps in the current knowledge base and provide clarity around the concepts within the study6,39,86. Although this is a strength of a scoping review, it does not allow for detailed information to practitioners or services that are trying to improve instances and services for survivors/victims of IPV and SV in RRN. Further research, as well as a systematic review of best practices, is warranted.

Conclusion

In addition to providing a review of the current literature regarding SV and IPV in RRN areas, this article also provides guidance for future researchers in this area. Future research could target and share the experiences of victims/survivors of SV and IPV in RRN areas. By increasing the voice of victims/survivors in this area, there is potential to advocate for more services, as well as reduce stigma in these areas. Something must be done to decrease the rates of IPV, SV, and GBV in RRN areas. Further research and knowledge development could be vital in advancing prevention efforts.

Funding

The research was funded by the Faculty of Health Studies (FHS) & Centre for Critical Studies of Rural Mental Health (CCSRMH), Grant Spring 2024.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have conflicts of interest to report.