Context

The Rural Adversity Mental Health Program (RAMHP) was founded in 2007 as the Drought Mental Health Assistance Program (DMHAP). The specific focus of DMHAP was to improve the mental health of New South Wales (NSW) farmers who were experiencing high levels of stress associated with the Millennium Drought (1997–2010). For historical program details, see elsewhere1,2. Since its inception, successive re-funding has enabled the program to evolve strategically and expand its reach beyond farmers coping with drought to the broader rural and remote NSW community. The program now provides assistance during other climate-related stressors (such as fire and flood), which affect farmers and rural communities most severely, and in everyday circumstances. The current overarching aim of the program is to identify people in rural and remote NSW who need mental health assistance and connect them to appropriate services and resources.

Currently, 19 RAMHP coordinators act as frontline staff (these staff have had different job titles through the life of the program) across nine NSW Government rural and remote local health districts (LHDs). Coordinators are co-managed by the Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health (CRRMH) and the LHDs. The CRRMH oversees the coordination of the program, while the LHDs facilitate the response to local mental health needs and ensure coordinators remain connected to their local mental health services. Coordinators draw on their local knowledge and established networks (often coordinators have worked locally in a variety of health roles prior to RAMHP, such as social work or nursing). Coordinators provide a point of communication between the LHD, local service providers and their communities. For example, coordinators may increase the local LHDs’ and service providers’ awareness of the issues affecting the mental health of their community members.

The program continues to be needed to help overcome the poorer mental health services access rates of people in rural and remote Australia compared to their metropolitan counterparts. Despite the prevalence of mental health disorders being relatively similar across Australia3, substantially fewer mental health services per capita exist in rural and remote Australia compared to major cities4. Four times as many psychiatrists and psychologists and almost three times as many mental health nurses are employed in major cities, per capita, than in non-metropolitan areas4. Moreover, a number of studies indicate that people in rural and remote Australia are much less likely to use available services than city dwellers5-7. Longer travel and wait times, higher financial costs and limited choice of treatment act as deterrents to service use8. The likelihood of accessing treatment may be further reduced by attitudinal factors prevalent in rural and remote areas, such as low rates of mental health literacy5,9, high levels of stigma associated with mental illness10 and stoic, self-reliant attitudes about help-seeking10,11. Possibly associated with this lower service access, overall non-metropolitan Australian suicide rates are 50% higher than in major cities (15.3 people per 100 000 in non-metropolitan areas compared to 10 in major cities)12. However, suicide rates vary greatly from one rural area to another13. The combination of stressors affecting rural and remote Australians, coupled with structural and attitudinal barriers to accessing treatment, and the apparent local inconsistencies illustrated by differing suicide rates, indicate the need for tailored approaches to improve the mental health outcomes for these populations.

RAMHP has therefore developed into a responsive program that provides individually tailored advice about mental health services, mental health promotion and training. Coordinators have a flexible role in which they are able to address broader social issues affecting mental health, such as financial, housing or legal concerns, and they are able to respond to unpredictable issues, such as environmental disasters, as they arise. The program provides a soft entry point to services for community members through the coordinators, who position themselves outside the clinical environment and engage people in one-to-one conversations about mental health, at, for example, community events such as agricultural field days and flood recovery meetings. This strategy broadens the reach of the program into traditionally hard-to-reach demographics, such as people who are hesitant to access mental health services.

In 2016, RAMHP was re-funded for 5 years, which provided the opportunity for a comprehensive review and longer term planning. Several priorities influencing program reorientation were evident at this time: the need to improve data collection and evaluation methods, a reassessment of the program’s primary focus and the need to align with significant government mental health reforms. This article reports on the reorientation process including the development and use of a program logic model (PLM) to enable program implementation. A PLM is a:

… schematic representation that describes how a program is intended to work by linking activities with outputs, intermediate impacts and longer-term outcomes. Program logic aims to show the intended causal links for a program14.

Issue

From 2007 to 2015, RAMHP was limited by funding periods ranging from 6 months to 3 years. In the period prior to 2016, program monitoring and evaluation data were limited. Assessment of program achievements was minimal. Data were collected inconsistently because evaluation was perceived as a low priority and there was a lack of clearly defined collection methods.

As previously mentioned, the 5 years of funding from 2016 enabled comprehensive planning and evaluation, including the opportunity to assess longer term program outcomes. This review of operations particularly noted that the planned activities and the objectives of the program had not been clearly articulated. In addition, data were not being consistently recorded to enable ongoing assessment of the program. Hence, a PLM was developed to clarify the program objectives, activities and anticipated outcomes and facilitate evaluation. Furthermore, a mobile app was developed to increase the specificity and depth of program data collected.

The expansion of the program’s focus, to include all people in rural and remote NSW in need of mental health assistance, coupled with the autonomy of coordinators to identify and respond to localised concerns, meant the program was working with a widening variety of issues and populations in increasingly diverse ways. In addition, coordinators were inclined to deliver activities that aligned with their prior occupational experience and skill sets. For example, coordinators with a clinical background tended to work with clinicians, whereas those with health promotion backgrounds were more comfortable performing community-based roles. The diversity of the program and the lack of role clarity led to difficulties communicating RAMHP’s value to stakeholders.

Considerable reorientation of RAMHP was also necessary to align with new state and federal priorities. The mental health system in which RAMHP operates had been significantly redesigned following the National Mental Health Commission’s 2014 review. The resulting redesign emphasised regional planning and commissioning through the development of 31 Primary Health Network regions and adopted a stepped-care model15. Stepped care aims to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of treatment by matching people to an appropriate level of intervention for the severity of their mental illness. Stepped care was viewed as a means to deploy the concentration of resources away from acute care and increase those for early intervention. RAMHP responded by shifting the program’s focus to early intervention, which prioritised connecting people to appropriate mental health services and resources for their particular needs.

Program logic model development

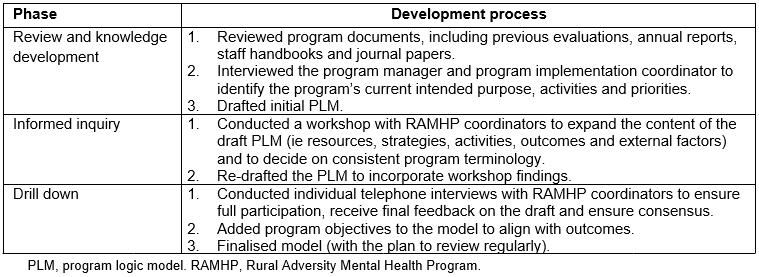

Development of a PLM was fundamental to the initiation of program redirection to reassess and clarify RAMHP’s scope, activities and anticipated outcomes. An approach similar to that of Peyton and Scicchitano’s ‘drill down method’16 was adopted to develop the PLM (Table 1). Importantly, this approach allowed the perception of common ownership by involving all stakeholders and agreement on terminology to facilitate communication. Furthermore, the approach provided the opportunity to collectively question assumptions associated with the program’s operations, activities and impacts. It was anticipated that the PLM would provide a one-page, accessible reference, communication tool and a logical basis for the development of an evaluation framework14,16,17. Thus, the PLM also facilitated the development of a mobile app to be used by coordinators to collect up-to-date data to support monitoring and evaluation of the program.

Table 1: Development process for RAMHP’s program logic model

In keeping with the drill-down method16, development of the PLM went through phases of review and knowledge development, informed inquiry and drilling down (Table 1). In 2016, the RAMHP evaluation manager drafted an initial PLM following consultation with senior management and a review of program management documents. The draft was presented to all RAMHP coordinators at a one-hour workshop where the team worked together to review and refine the model. Following the workshop, the evaluation manager re-drafted the PLM to incorporate the workshop outcomes and used this revised model to conduct individual interviews with all coordinators to assess its accuracy and make further revisions. Interviews were semi-structured, collecting information on the participants’ perceptions of the program’s operations, reporting and communication systems and partnerships. Revisions continued until consensus was reached that the PLM accurately described program operation and reflected what was required to meet the needs of rural communities and maintain relevance in a system under reform. RAMHP is a dynamic program that needs to flexibly respond to changing conditions and demands. Hence it is Important that the PLM is not a static instrument and will be subject to regular review16 at key times, such as when the program is re-funded.

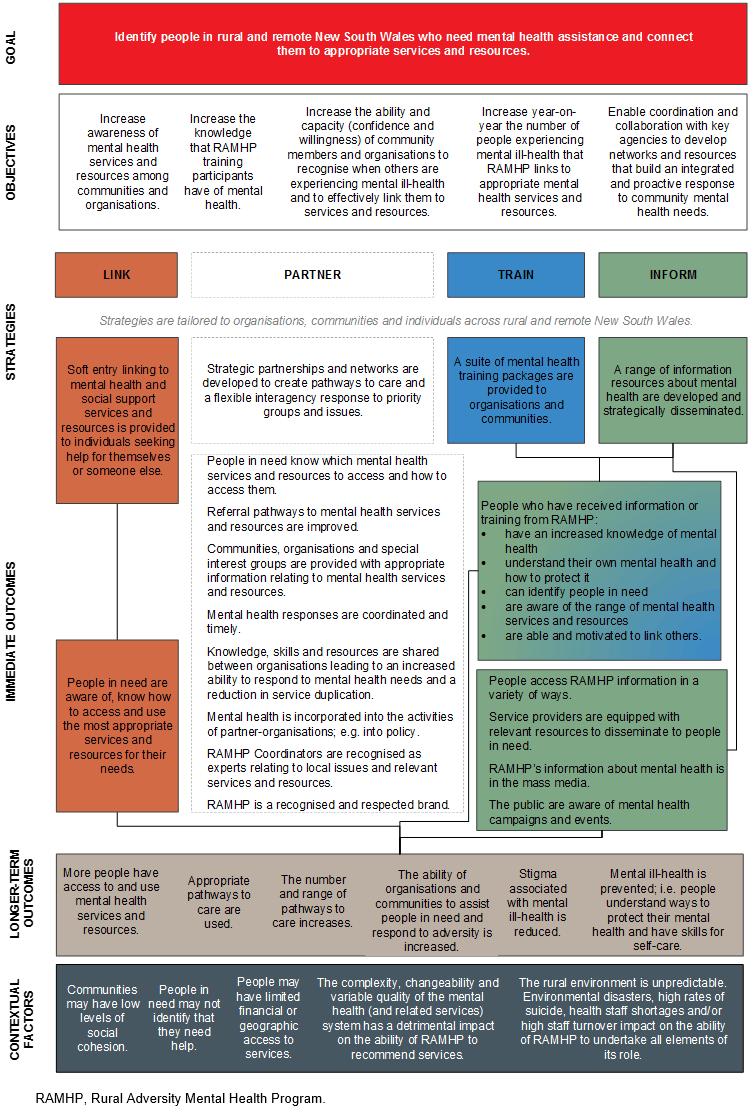

The process of developing the PLM created a framework for coordinators to discuss whether activities were consistent with the new strategic priority17 of connecting people to mental health services and resources. Many previous program strategies, such as capacity building through strategically delivered training, were maintained. Conversely, activities not demonstrated to help connect people to services, such as hosting community barbecues, were abandoned. By clarifying activities that were consistent with the objectives of the strategic priority, it was apparent that RAMHP’s diverse range of activities could be crystallised into four key strategies. It was then possible to demonstrate how each strategy connected people to mental health services and resources (Fig1).

The four strategies were:

- inform – produce and disseminate standardised information about mental health and available services and resources through a wide variety of channels targeting rural and remote people

- link – provide personalised advice to link individuals who need assistance to the most appropriate services and resources

- train – build capacity by providing standardised training to enable community members and workplaces to link people to services and resources

- partner – work in partnership with relevant stakeholders to create pathways to care and a flexible inter-agency response to priority groups and issues.

Figure 1: Logic model of the Rural Adversity Mental Health Program.

Figure 1: Logic model of the Rural Adversity Mental Health Program.

Lessons learned

Stakeholder agreement

PLMs are important engagement tools that can facilitate stakeholder approval across all levels and reduce potential misunderstandings when sufficient time and resources are given to their development16,17. The involvement of the RAMHP coordinators in the development of the PLM was vital to fully gauge the breadth of the program and to ensure the acceptance and adoption of strategic changes among coordinators18. The PLM provided an interactive structure for RAMHP coordinators to share their perspectives, which resulted in clarity and agreement about program activities and roles.

Pressures relating to program re-funding, staff changes across organisations and mental health system reform meant that the involvement of other key stakeholders, such as LHD managers and partnering organisations, in the development of the PLM was limited. Involvement of more stakeholders may have improved the model.

Communication

The collaborative development process also provided the opportunity to determine consistent terminology to describe the program. This meant that RAMHP coordinators could clearly and consistently articulate their role to external stakeholders, such as service providers, increasing the likelihood the program would be utilised. In addition, as RAMHP was operating in a system undergoing significant reform, being clear about the program’s purpose was especially important to maintain a straightforward, visible and strategic program profile.

Reassessing RAMHP’s primary focus to align with mental health system reform

The PLM emphasised connecting people to support options, via the four program strategies, providing clear guidance to coordinators regarding centralised program expectations that aligned with changes in the mental health system. The PLM was intended to be a conceptual guide rather than a prescriptive plan18. Hence, program strategies were broad enough for coordinators to adapt activities to the specific issues facing their geographic regions. This enabled a balance between statewide objectives and local relevance. For example, a coordinator could respond to a high local suicide rate by prioritising delivery of centrally standardised RAMHP training. Maintaining RAMHP’s flexibility to respond to local need, such as unpredictable environmental disasters, is an enduringly valued feature of the program among stakeholders.

Evaluation and accountability

The PLM provided the foundation for the development of an evaluation framework, program objectives (Fig1) to measure progress against, and a structure to determine the types of data required to inform program improvement and ensure accountability. As well as the overall evaluation framework, the PLM informed the development of individual evaluation instruments and a mobile app. For example, a short survey given to training participants is directly linked to outcomes in the PLM. The app is of major importance to the evaluation framework. It was created to provide a targeted data set that would allow the reach of the program (characteristics of the people reached and how many) within each of the four strategies to be assessed. The measures included were decided upon by considering the outcomes detailed in the newly developed PLM and what had previously been reported. Coordinators access the app on tablet devices and complete a short, structured survey each time they link a person to a service or resource, provide training or attend a community event or professional meeting. As the app is structured on the PLM, coordinators understand why data are collected, which increases compliance, and while RAMHP coordinators enter data the program objectives are reinforced.

The reports resulting from the app benefit RAMHP in many ways. Monthly and quarterly reports provide RAMHP coordinators with timely feedback. This increases their awareness of the impact of their activities, raises their motivation and assists them to self-manage, review and strategically plan their work. These reports also benefit LHD managers by providing regular updates about the RAMHP coordinators’ activities. In addition, being able to report interesting and relevant information about program activities and outcomes externally allows RAMHP to confidently articulate the program’s value and raise its profile. Developing the PLM was a fundamental step to incorporate evaluation into the early stages of program renewal, rather than at the end of the funding period. This helped to ensure that program evaluation was established on the underlying program principles and allowed integration of evaluation and program planning17.

Conclusion

This report underlines the need for sufficient time and resources to be invested in the development of a PLM in order to maximise quality and, hence, usability. The development of the PLM has proven valuable in RAMHP’s reorientation process. RAMHP’s PLM has assisted in reassessing the program’s primary focus in order to align it with significant government mental health reforms. It has enabled an improved evaluation framework to be implemented including a bespoke mobile app and other targeted data collection instruments. The collaborative approach to PLM development was critical to engage coordinators in program changes and resulted in improved role clarity and communication. Therefore, RAMHP’s PLM has been an important foundational tool to reorient the program and create clear structure and evaluability. The rural and remote communities RAMHP serves also benefit as the PLM aids in the delivery of a program that is productive, accountable and appropriate.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Diane Gill and Trevor Hazell for information about RAMHP’s history; Kristina Gottschall, Angela Booth, Tonelle Handley, Scott Fitzpatrick, Grace Hopkins, Lucy McEvoy and Sophun Moch for comments on the concept; and to Daniel Hudspith for editorial advice.

References

You might also be interested in:

2020 - A bitter pill to swallow: registered nurses and medicines regulation in remote Australia

2013 - Progress towards TB control in East Kwaio, Solomon Islands