Introduction

The need for family physicians in rural areas across the USA and Canada has been well documented1-3. Since family physicians constitute the largest population of rural practitioners, the problem has been exacerbated by a sharp decline in medical students’ interest in the field of family medicine4 and the aging of the current rural workforce5.

The need for physicians is especially acute in the north-west, where a vast physical frontier constitutes one of the most rural segments of the USA. Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Washington and Wyoming, for example, encompass 27% of the nation’s land mass and only 3.3% of its population6,7. The practice of family medicine in these areas is very broad in scope and covers a diverse population in terms of age and health status. Physicians there must perform a wide range of procedures and be available for long hours of call.

Although women are more likely than men to go into family medicine, they are less likely to practice in rural areas6,8,9. Female physicians are more likely to attend to births and women’s health issues than their male colleagues10,11, and rural areas suffer from a shortage of obstetric providers12. Recruiting, retaining and promoting the success of female physicians in rural communities are therefore crucial steps in improving rural health.

The most salient factors for recruiting and retaining female physicians can be subsumed under the category of support – through organizational structures and practices, networks of people, and personal coping strategies that give women a sense of control over their time and resources6,12.

This qualitative study provides a more in-depth examination of the types of support female physicians need and how they find it, as well as how their needs change over time. The context of support used to guide this research was informed by the literature on gender differences between male and female physicians, as well as research on emotional labor, especially as it applies to the practice of medicine. The findings, which are consistent with earlier research on female physicians, provide a better understanding of the strengths and limitations of current medical training and identify information for future training that would improve women’s preparation for rural family practice.

Methods

This was an exploratory descriptive study using a phenomenological approach to data gathering and analysis13,14. The goal was ‘to capture the meaning and common features, or essences, of an experience or event’14, in particular the lived experience of female physicians practicing in rural areas in the north-west region of the USA. Many themes emerged, including areas of adequacy and inadequacy in preparation for rural practice, but these are beyond the scope of the present article. The purpose here is to illuminate the experience of female physicians in finding, developing and maintaining support systems they feel are necessary for a successful work–life interface. Results of the study are ‘phenomenologically informative’ in regards to the thoughts, feelings and perspectives of rural female practitioners12.

A purposive sample of 20 female family physicians who had graduated from the same program, the Family Medical Residency of Idaho (FMRI), participated in this study. Participants were identified from graduation records from FMRI and included all graduates who self-identified as female, had completed residency or fellowship training in 2015 or earlier, and practiced in Rural–Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes 4–10 in the Pacific north-west, including Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Utah and Nevada. All physicians who met these inclusion criteria were contacted by the primary investigator and invited to participate in the study. No incentives were offered.

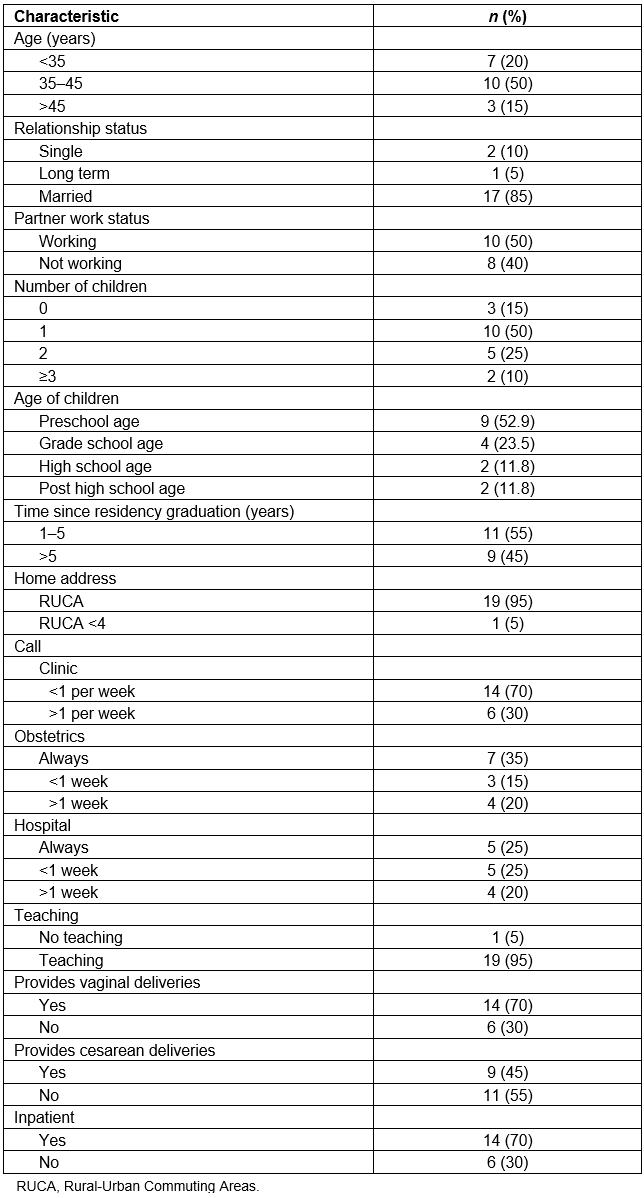

The semi-structured interviews, 18 in person and two by phone, were conducted to gather information about respondents’ preparation for rural family medicine, daily practice, work–life interface and overall quality of life (Table 1). All interviews were conducted by the primary researcher, a former rural family physician and faculty member of FMRI. The interview format and questions were informed by the literature and developed in consultation with researchers and practitioners from FMRI. Although work–life balance has been a focus of interest in the medical literature, particularly in regards to female physicians1,7,15, medical researchers have not questioned the terminology. However, researchers in other fields, such as organization and management, have challenged the phrase ‘work–life balance’ because it implies that work and life can be compartmentalized and equally apportioned when in fact the two often overlap and are disproportionate in terms of the time and attention paid to each. For these reasons, the term ‘life–career interface’ was used and framed as ‘How satisfied [or happy] are you with your life–career interface?’

Interviews were conducted between June and October 2016. The physician–peer interview approach may lead to greater disclosure and more meaningful conversations than interviews conducted by non-physicians16,17. In keeping with the phenomenological method of observing participants ‘in context,’ the primary researcher traveled to remote locations and interviewed most of the physicians in their homes and offices. The interviewer formulated overall impressions afterwards and reflexively noted her own presuppositions, surprises and emotional reactions18. All interviews were recorded to a secure electronic device. Collected data were de-identified using a master list of participant names and a unique identifying number.

After the interviews were completed, they were transcribed verbatim by the primary researcher, transported into Dedoose, a digital program for coding qualitative and mixed methods research, and initially coded by the primary researcher. A descriptive coding framework was developed around the interview topics. Among the key themes that emerged from the first coding was the necessity of support systems. Subsequently, two other members of the research team, neither of whom were physicians, downloaded the transcripts on their laptops and recoded them intuitively. In that process, the descriptive codes related to support were divided into subcodes. All three researchers used an immersion and crystallization approach in which they immersed themselves in the transcripts by reading, rereading and note-taking; reflected individually and collectively on the data analysis; and co-identified emergent themes and subthemes19. Discussions of the data and coding were held with the full research team – an interdisciplinary group of researchers in public health and the social sciences – to resolve differences in interpretation and to discuss implications.

Table 1: Key interview questions

Ethics approval

All research procedures were approved by the University of Washington Internal Review Board (#51665).

Results

The team analyzed 20 transcribed interviews, which were an average of about 5300 words in length. Participant demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. Participants ranged in age from 31 to 59 years and career stage from 1 year out of residency to 25 years out of residency. Two participants were single, one participant was in a long-term relationship and 17 were married. Eighteen of the participants had children.

Many had difficulty calculating the number of hours they actually worked, although most worked full time. For example, one physician (participant 3) stated that she worked about 40 hours a week, with office hours from 7.30 am to 3.00 pm, but that did not include 24-hour call one day a week, baby deliveries and additional shifts as needed. She was also serving as medical director for the Emergency Medical Technicians in several counties. Considering these responsibilities, she actually worked about 65 hours a week. Another physician (participant 4) responded with a range of hours: ‘Scheduled for about 45 to 50 hours a week but probably work about 60 to 70 a week.’ These calculations did not include hours teaching, although many of the physicians mentored pre-med students, physician assistants and residents.

Given the long hours and the multiple and varied responsibilities of rural family medicine, physicians discussed the types of support they relied on to manage their work and personal lives. Major sub-themes included the necessity of family and social support systems, self-care practices, systemic support in the practice environment, and access to professional mentors and continued education.

Family support systems were crucial, starting with the spouse. Besides strong support at home, extended family, friends and paid caregivers were also important. Self-care practices, such as limiting or avoiding time spent charting at home, turning off electronic devices, exercising, pursing hobbies and, for one physician, daily prayer, were crucial. At work, systemic support was necessary to assure flexible hours, including the ability to limit or avoid on-call hours and to change the scope of practice. Access to other physicians and medical staff and time for continuing education also helped practitioners remain engaged and avoid burnout.

Table 2: Characteristics of study participants

Spousal support

All of the married participants with children focused on how important their spouse’s role was in helping them sustain a successful practice. They noted that a stay-at-home dad was ideal, although not always possible, and that women considering rural family practice should choose their partners carefully.

One physician who was happy with rural practice described her husband of 8 years as the ideal partner. The husband grew up in a small town with a family physician father and understands the commitment involved. The physician (participant 5) described him as an ‘emotionally balanced male, [so] we don’t have the conflicts I see a lot of female physicians struggle with, that power struggle’. This couple relies on family members for care of their three-year-old. Her parents moved to the area and provide what the physician described as ‘incredibly monumental support’. She finds that only with the combined assistance of her husband and parents is she able to practice full-spectrum family medicine.

Many of the physicians described supportive partners in terms of their attitudes as well as behaviors. One woman (participant 8) said of her husband, ‘I married the right person. Very supportive, very much like, do what you gotta do … So he does everything at home, you know from renovations to horse-shoeing, to fencing, to taking care of our child, which is the biggest thing that he does.’ Another physician (participant 15) explained that she could not be a rural physician without the emotional support of her husband, who ‘never questions when I’m away, never makes me feel guilty about the hours spent in the hospital or clinic.’

Even with a stay-at-home spouse, traditional gender roles often come into play. Said one physician (participant 19), ‘I think as a female, it does not matter if you work and you are the sole earner, when you come home you are mom, and you are expected to be mom. It is different coming home being dad … It is a different relationship.’ Physicians tend to be high achievers who want to excel in all aspects of their lives:

I think going into medicine, a lot of us do have a pretty Type A personality, and we want to give a hundred percent to everything. You want to be a very good mom, and you want to be a very good doctor … In a way, you feel like you are always letting one part of you down. Like you need some personal time, but you haven’t seen your daughter for a few days. You want to give so much, but sometimes there’s no more left to give. (Participant 20)

Support from family, friends and community

Besides a supportive partner, help from a larger network of family members, friends, neighbors, and paid caregivers is also necessary. Friends and neighbors often provide emotional support, as well as child care. As one new physician (participant 18) said, ‘It’s [reassuring] having other families that we can relate to and support one another and do things together.’ An experienced physician (participant 16) in her 40s with two children between the ages of five and eight said, ‘I have several really good friends who also have kids, and one’s actually a stay-at-home mom. And the other one I work with is a nurse practitioner, so I feel like I get a lot of practice and then mom support to go with that …’.

Moving to a familiar area makes it easier to develop a support system. For this reason, the single mother in the study (participant 17) returned to her home town in ‘the boonies’ to practice medicine. She and her teenaged daughter moved into the family home with her parents and older brother. Even so, she chose to limit her scope of practice to leave more time for family life. Two years out of residency, she described herself as happy and her life as ‘fairly well balanced’, primarily because, in choosing not to practice obstetrics, she has ‘more time to be a mom.’

Without a stay-at-home spouse, family or friends, paid caregivers become more important, and they are sometimes difficult to find and keep in rural areas. A physician whose husband works full time and who has no family in the area described the dilemma of child care:

If your kid is sick, who is going to leave early to go pick up your kid? And the day care hours here, nothing goes beyond 4:30 or 5, and [my husband] works from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m., so we have to hire another babysitter that picks the kids up and brings them home, and they’re constantly turning over because no one wants that job. And there are the multiple meetings per month that are outside those hours that I generally feel obligated to [attend]. (Participant 18)

Over time, most of the respondents came to feel supported by small town life. As one physician (participant 16) said, ‘Never underestimate the value of living in a small town and being able to run to the post office in the middle of winter and leave your car running and your kids in the back.’ Raising children, with their associated activities, helped the experienced physicians become integrated into the community. Another physician (participant 7) explained, ‘When you run out and take care of the concussion on the soccer field, I think that stuff is really great. It integrated me. It didn’t always allow me to separate [work from life], but you accept that when you go into rural practice.’

The one thing that sustained all of the physicians was their relationship with patients. The doctor–patient connection is what brings joy and helps every one of them cope with the harder aspects of life in rural areas. Although not all relationships are positive, the good ones make up for the challenging ones. For many respondents, practicing obstetrics and pediatrics was the most rewarding aspect of rural practice. ‘Delivering babies and helping new families get started makes rural practice feel significant’ (Participant 1).

Rural female physicians also like hearing their patients’ stories and providing care to multiple generations of the same family. This is a time-intensive way to practice medicine, but it is what makes rural practice interesting and meaningful. Said one physician (participant 15), ‘Those relationships are ones where you’re like, 'I know every visit I have with you is going to take 45 minutes, and it doesn’t really matter because I just want to hear about how life’s going and see if there’s any way I can help'.’

One physician described the doctor–patient relationship in spiritual terms:

When you’re in the room with the patient, at least many of them, there’s just a touching of souls. I can’t describe it any other way. I had a patient who died of a massive cerebral hemorrhage when she was 45, and I had been her doctor for three years as a resident, and her family waited for me to get over there before they pulled the plug. All the rest of the family was there, but they waited for me to get there, and when I walked into the ICU room, it was like the waters parted, and they wanted me to stand there at the head of the bed. You could see the layers, the direct family is right here, and there’s the aunts and cousins, and then there’s the friends, and they wanted me right at the head of the bed in the inner circle when they pulled the plug. (Participant 9)

Self-support

Responses to questions about what brought them to rural medicine, what brought joy to their work lives, and how they found a ‘resilience point’ to keep from burning out often elicited talk about self-care – beliefs and behaviors that help the physicians maintain a sense of personal health and wellbeing.

From the beginning, the decision to practice rural medicine was a lifestyle choice for most of the respondents, which is a form of self-care. Pursuing personal values and interests was a strong motivation for rural practice. Said one physician (participant 15), ‘We did a lot of research on where we wanted to go, and we did a lot of soul searching and a lot of talking to people and really thinking about what was important to us … I wanted to do something where every day would be crazy and unique and you never know what you’re going to see and would challenge you intellectually and emotionally and physically.’ Another physician (participant 18) chose to practice in a rural setting because ‘my quality of life and place of living have always been really important to me. When I look back on why I went to medical school in the first place, it was so I could get back to a small ski town where I could do the things I love to do in my time off.’

Staying in touch with personal interests and hobbies and making time to pursue them was recognized as a factor in avoiding burnout, although some physicians were more successful at this than others. Respondents had to make a concerted effort to carve out time for themselves. One physician who was completing her first year of rural practice had started a monthly social group to try to rekindle outside interests.

Establishing strong coping skills is important, too. This includes adapting and being willing to learn on the job, accepting one’s strengths and weaknesses and managing feelings of inadequacy and guilt. Rural physicians must be confident in what they know as well as comfortable with uncertainty. This dynamic was explained by one of the more experienced physicians, 13 years out of residency:

You know, I see a lot of residents, and I will be like, ‘Come in here and do this procedure.’ [And they will say] ‘Oh, I’ve never done that procedure. I’m going to watch this one.’ And I’m looking at them saying, ‘No, you really are just going to do it, because otherwise you might not see another one. You just gotta do this.’ (Participant 11)

Being called upon to ‘just do it’ is one of the most challenging aspects of rural medicine for new physicians. A physician who is 5 years out of residency (participant 3) described her early feelings of inadequacy: ‘The first year is all about fear of not having backup. You have the skills. It’s just that you have to trust yourself and then you have to just know that whatever is going to happen, no one else is going to be there, so you just have to do it.’

Limits to community support

There are downsides to rural practice, too. A physician practicing for less than 4 years was surprised by the onslaught of patients when she began practicing:

I was not prepared for how people sort of glom onto a new doc in a small town and try to get needs met they haven’t been getting met … whether that’s opioids, whether that’s other controlled substances, whether it’s mental health … If you’re not the kind of person who’s willing to draw boundaries, stick to your guns, you can just be ‘killed’. And I saw that happen to one of my practice partners. (Participant 10)

In rural areas it can be difficult to establish boundaries, to create a private life and even to get out of town. The most experienced physician in the study (participant 7), 25 years out of residency, reflected on her life as a physician in a small town and described the benefits and disadvantages, which are sometimes the same thing. She finds it rewarding to be valued and respected, but she has a hard time getting away from patients, which she discovered when she took time off. ‘Twelve weeks is all I took, and people thought I was gone for five years. People were stopping by the house, knocking on the door, sending me things. It’s hard to escape that in a small town, so you really have to disappear when you leave.’

Support from medical partners and practices

Rural physicians also need supportive work partners and a practice system that advocates on their behalf. The physicians in this study described what they would look for if they were again looking to select a rural practice location. They described the importance of researching the area and the medical practice itself. Besides the town and its proximity to family and other support networks, it is also critical to consider the gender and age of the other physicians, the group dynamics of the medical practice, the sufficiency of support staff, and the level of administrative support available.

One physician (participant 4) felt fortunate to be in a practice with five other female physicians under the age of 45 years, which she acknowledged is very unusual for a rural practice. ‘I looked at other practices where it was definitely more older males, and that actually steered me away from the practice. I have supportive colleagues who are of a similar mindset to me, and I think that’s been helpful in setting up my career.’

Diversity in age can be a factor in creating a good learning environment. Said one physician (participant 5), ‘The great thing is I’ve got colleagues that have been out and practicing forever, and I’ve got colleagues that are brand new grads.’ She asks the new graduates ‘stupid questions’ that she would be ‘embarrassed’ to ask the experienced physicians and reserves the more complicated questions for them.

An experienced physician, 15 years out of residency (participant 16), talked about the necessity of finding female mentors in the early years, especially if there are not many female physicians in the area. Her advice to new physicians was to get a support system in place immediately, because ‘you’re going to be relatively isolated from other females, you’re going to be isolated from academia.’ She felt she had not done a good job of this herself: ‘I felt like I could rely on my male colleagues, but it’s entirely different. They have an entirely different support system among themselves … They found their support in going and coaching a football game together … but that wasn’t necessarily that supportive for me.’

In offering a final piece of advice, one physician (participant 9) recommended finding ‘a really good group to practice with’, which she explained in terms of her own experience working in two small towns just 110 km (70 miles) apart. One town had a solo practitioner and two small groups of physicians that were all ‘stabbing each other in the back’. The second town had two groups of family physicians that shared a far more collegial atmosphere, and this is where she chose to practice.

A good nurse and other staff are important and sometimes hard to find in rural areas. ‘They tell you that you can hire your own nurse when you come in, but there is a shortage and a lot of turnover,’ said one physician (participant 19). She noted that, because two of her partners had not had a nurse in 3 years, she felt lucky to have one, although she did not think they related to one another very well, which was a continual source of stress for her.

Administrative support is not only necessary for effective contract negotiations, adequate maternity leave and flexible work hours, but also for much-needed emotional support. One experienced physician (participant 11), 13 years out of residency, had come to appreciate the value of a good manager: ‘I feel like my boss is a good support. She’s a friend as well. Our executive director, I can go to her whether it’s professionally or personally, and she usually can tell when things are getting rough and what’s going on. [She will ask] 'How can we shift things and change your schedule?'’ Another (participant 14) described the importance of having administrators who want you ‘for the marathon, not for the sprint’ and treat you accordingly.

Life–career interface

Respondents seemed to appreciate the wording of the question about balancing work and life. One physician (participant 1) commented, ‘I like that you call it interface because there’s no bounds, there’s give and take.’

The consensus of respondents was that the career–life interface varies across individuals, changes over time and is always a work in progress. The two single physicians in the study, ages 31 and 34 years, described their career–life interface in positive terms, even though most of their time was spent working. One described this early period as ‘good’ because she could be ‘selfish’ and focus on her career. She noted that, when you are new to an area and living in a small town, a lot of your friends are the people you work with, which makes the life–career interface easier. The other woman (participant 17), the single mother of a 14-year-old daughter who resided with her parents, said of her life, ‘I’m loving it. It’s absolutely jam-packed full with mom responsibilities and work responsibilities, but it’s a good balance.’

The married physicians described their career–life balance in a variety of ways, ranging from ‘happy’ and ‘satisfied’ to ‘not good’ and ‘not satisfied.’ Those who were satisfied said that it had taken a while to get to there. Those who were moderately or somewhat satisfied said that it ‘depends on the day’. Those who were dissatisfied usually were in a practice situation over which they had little control, were working too many hours, and were feeling unappreciated and under-compensated.

One piece of advice offered for creating an effective career–life interface was to keep the big picture in mind. A physician who was 2 years out of residency (participant 20) and had a three-year-old child said she was ‘still trying to figure out’ how to manage work and life, but her advice to physicians considering rural practice was this: ‘If it is truly what you want to do, and you are passionate about it, you can make it work. As daunting as it seems sometimes to be a physician in a small town and a mom, I think there are awesome rewards from it as well.’

Discussion

While these findings correspond with previous research on rural female physicians’ need for support, this study provides additional information about the types of support networks needed, as well as physicians’ resilience in developing and maintaining them. The interviews also provide unique insights into why female physicians in rural areas benefit from such a support system.

Besides wanting to practice good medicine, physicians in this study expressed a desire for positive relationships with their patients and colleagues, as well as the desire to feel part of their communities. This finding is supported by previous research12,20,21. In a survey of the recruitment experiences of rural physicians in the Pacific north-west, researchers found that women, more than men, took interpersonal factors, within the practice and in the community, into consideration when choosing a position22. In their telephone interviews with 25 female physicians practicing in rural areas across the USA, researchers found that a network of committed relationships, starting with a supportive spouse or partner at home and extending to outside relationships that help physicians feel integrated within the community, increases the likelihood of a successful, long-term career in rural medicine12,20. Additionally, ‘multidimensional’ patient relationships’ bring joy to the practice of rural medicine12. Approaching work in terms of these ‘relational practices’23, however, involves specific values, communication styles and forms of emotion management that are uniquely gendered.

Gender differences in doctor–patient communications are well documented. In a meta-analysis of 26 studies, researchers concluded that, while there is little difference in the amount or manner in which biomedical information is given, female primary care doctors engage in significantly more patient-centered communication (characterized by questioning and counseling, discussing emotions, giving feedback and enlisting patient input) and spend a longer time with patients (on average 2 minutes or 10% more) than their male colleagues24. The patients of female physicians talk more overall and discuss more psychosocial information than do patients of male physicians. They also provide more biomedical information, perhaps because female physicians’ questioning and partnership building encourages disclosure. These differences are clearly reflected in charting practices, as female physicians record proportionately more diagnoses of a psychosocial nature than do their male colleagues, which creates the need for more documentation24.

It is not just the number of hours worked but also the emotion involved that sometimes makes the life–career interface difficult. As one physician (participant 2) in this study noted, ‘The harder the days are, even if they’re not as long, you’re left a little short with your family at the end of the day. Sometimes I feel bad because I need to come home and just take some time to myself, but I don’t want to be away from them. But I’m also not really in a good place, so that kind of balance is hard …’.

This physician is talking about emotional labor, the process of managing feelings in accordance with requirements and expectations for interactions on the job and at home25,26. Research indicates that certain types of emotional labor, such as ‘surface acting’ or ‘faking it’, in interactions with patients negatively correlate with job satisfaction15. However, when caregiver and patient share a reciprocal, caring relationship and genuinely express those feelings, as is the case with many of the physicians in this study, work feels less emotionally demanding and more satisfying and meaningful for the caregiver26,27. Another physician (participant 15) relishes ‘those emotional connections’ with patients, even though they are sometimes difficult. ‘This week in particular has been really tough with two of my very favorite patients I diagnosed with terminal cancer. And so, that emotional-ness and feeling like you’re suffering with them is really tough. And I’ve thought a lot about is there a way to protect yourself from it? But I think that’s why I love it, and there are no walls.’

A sense of control over the type and amount of work one does can also moderate relations between emotional labor and feelings of burnout or job satisfaction28. Thus, physicians who have flexibility in selecting their hours and their scope of practice are better able to manage emotional labor and find long-term satisfaction in work. Other qualitative researchers have found that practice and employment characteristics contribute to professional satisfaction and female physicians’ desire to remain in rural practice. The quality of relationships with colleagues in the same practice, with other professionals in the region, and with role models and mentors greatly influences physicians’ sense of control over their time and the amount of flexibility they have in practicing medicine. Supportive relationships at work are especially important during times of transition and change, such as taking maternity leave, recruiting new practice partners and undergoing shifts in practice ownership, all high-risk periods for physician burnout20.

Conclusion

Residencies training for rural practice must acknowledge the need for support systems and teach how to build and sustain them. Female physicians will better understand the relevance of support networks when they understand the costs and benefits of emotional labor. Support networks mitigate the effects of emotional labor and help build resilience, a learned trait that is strongly associated with family physicians’ overall happiness and wellbeing17.

Building support starts with negotiating a contract that allows for a healthy life–career interface, including a workable family leave policy and flexibility. Negotiating a contract not only involves knowledge of alternative ways of practicing rural medicine, but also self-knowledge and the confidence to ask for what one wants and needs.

Limitations of this study include a geographically restricted sample that was too small to reach saturation and a lack of diversity in terms of race and ethnicity. It is descriptive in nature and does not provide quantitative data to support qualitative findings, although results are confirmed by previous research on rural physicians. Also, the study reports exclusively on physicians who are still practicing. A study of graduates from residency programs who have left rural practice would provide useful information about the situations that cannot be successfully negotiated and the intractable barriers to a successful life–career interface.

Future studies might examine more directly the similarities and differences between male and female physicians practicing in rural areas, including recruitment experiences, attitudes toward practice locations and partners, interactional styles and feelings toward patients, and strategies for building and maintaining support networks. Longitudinal research on changes in scope of practice and strategies for managing the life–career interface over time would provide insight into the sustainability of rural practice over the life course for both male and female physicians.

References

You might also be interested in:

2005 - Retaining rural medical practitioners: Time for a new paradigm?