Introduction

Community health worker (CHW) programs can play a significant role in improving health at a community level by providing a range of preventive and treatment services1. Large-scale national and government-led CHW programs have been implemented in many countries, including Brazil, India, Tanzania and South Africa2. While there are many success stories where CHW programs are effective, these programs are complex, and evidence of their effectiveness is not consistent – particularly when programs are scaled and moved to national oversight and control3. Implementation strategies, and the related effectiveness of CHW programs, vary considerably, and CHW programs face many implementation-related challenges hindering their success4. For many governments in low- and middle-income countries – where these kinds of programs have the greatest potential to improve health outcomes at scale – inconsistent or poor-quality implementation can feed uncertainty about whether CHW programs are worthwhile investments. As such, there is a risk that CHW programs may fall out of favour unless substantial improvements in the implementation are made4.

CHW programs are nested within a broader ecology of systems of local communities, district-level and national health care, and larger sociopolitical contexts. To apply a systems approach is therefore key in improving the implementation of CHW programs. It is vital to document views from a variety of stakeholders working in diverse roles within CHW programs, in order to further understand experiences of the processes that guide program implementation5. This approach may be especially useful when exploring implementation-related issues for CHW programs operating in low-resource settings or other challenging contexts. Enhanced CHW training, divergent views on task sharing, and the need for harmonizing support between different groups of stakeholders have all been described6,7, illustrating the important and unique insights that on-the-ground program stakeholders may be able to share to inform program improvement.

Recruitment, quality training, access to equipment, logistical support, and regular supervision are crucial building blocks of effective CHW programs3,8,9. However, these building blocks are often inadequate or absent, creating barriers for effective program implementation3,10,11. International agencies such as the World Health Organization have responded to these concerns by providing a roadmap to designing programs more efficiently and identifying implementation strategies that improve service delivery3. There has also been a call for robust research from on-the-ground actors such as implementing agencies and other CHW program stakeholders, as these perspectives have been regularly overlooked1,12.

In South Africa, inspired by the successful CHW program in Brazil, the South African Department of Health embarked on a quest in re-engineering primary health care and investing in a national CHW program in 20112. With this investment came the introduction of ward-based primary healthcare teams, and within these teams, the ward-based primary healthcare outreach teams (WBPHCOTs) – South Africa’s current CHW program. These teams work at the ward (subdivision of a municipality) level, where a group of six to ten CHWs conduct home visits and provide basic information on non-communicable diseases, HIV/TB treatment, and maternal and child health. CHWs in the ward-based outreach team (WBOT) system are supervised by primary healthcare clinic managers and operational team leaders, typically enrolled nurses, who are responsible for supervising CHWs13-15.

Although the WBOT strategy has the potential to transform health outcomes and streamline services by providing health services to communities16, significant challenges have been reported relating to training, supervision and access to equipment and transport11,17,18. CHWs in South Africa have the potential to improve health at a community level and increase access to health care, particularly in rural areas – but there are significant concerns about the implementation and effectiveness of the government-implemented CHW program – understanding the range of factors influencing program efficacy is key to enabling improvement of the program17.

As part of a cluster randomized controlled trial (cRCT), evaluating a supervision model with the government-implemented CHW program, mid-level stakeholders (in this case, CHW supervisors, primary healthcare clinic personnel and program managers) were interviewed. We aimed to understand their perspectives on the standard and the enhanced-supervision CHW program and hypothesized that stakeholder perspectives would provide valuable insights on how the supervision model in the enhanced-supervision intervention was experienced and provide guidance on how to improve the implementation of CHW programs in South Africa and globally.

Methods

The study was conducted in the O.R. Tambo District, in the rural Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The district is one of the most under-developed and impoverished municipalities in the country and ranks below national standards in terms of access to water, health care and employment levels19. Previous research on mothers in the area reported an HIV prevalence of 29% among pregnant women. Furthermore, 5% of mothers have never attended school and only 6.6% had a high school diploma, and 92.5% of households received some kind of government grant19. Health care is provided by a government district hospital and surrounding primary care clinics, although there are a few private healthcare practitioners in the area. There is a long history of CHW programs in the area, implemented by both non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and, more recently, the Department of Health. The geography of the study area is challenging, with limited infrastructure in term of tarred roads, access to water and electricity.

The intervention

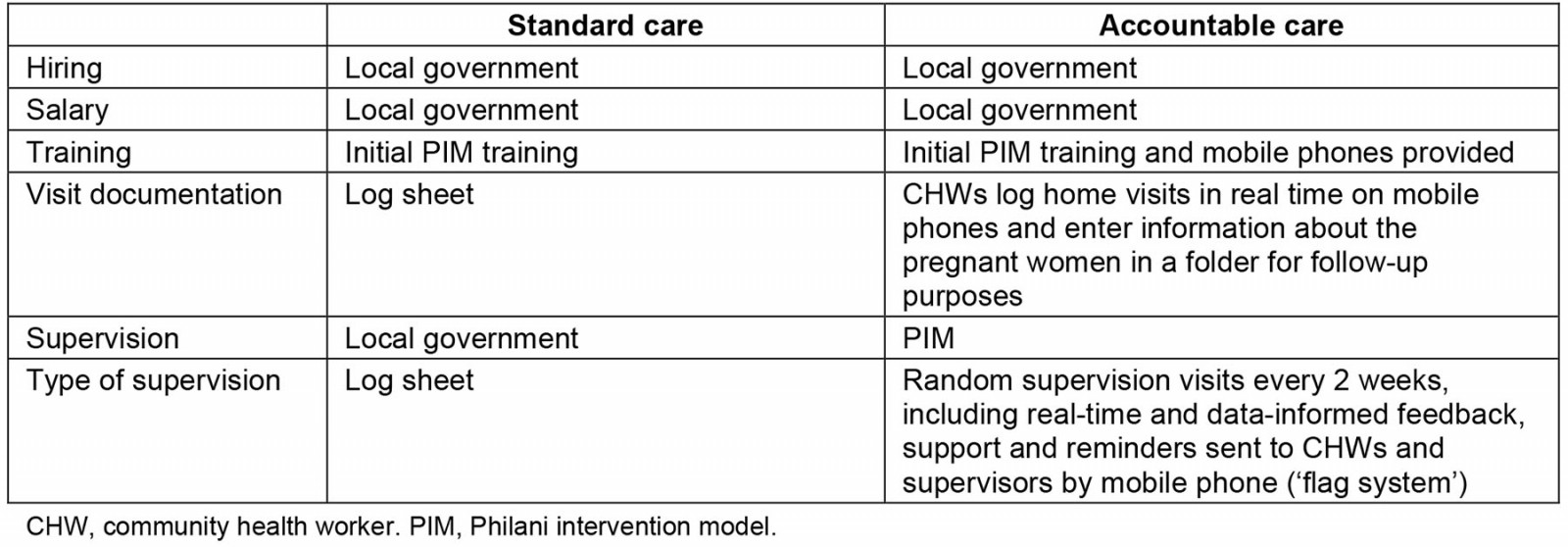

This study is a qualitative descriptive study drawing from semi-structured interviews with stakeholders and supervisors enrolled in both the intervention and control arms of the cRCT titled Eastern Cape Supervision Study. The objective of the cRCT was to investigate whether good-quality supervision and support provided to South African government CHWs improved maternal and child outcomes when compared to routine supervision as delivered within the primary healthcare system. The enhanced-supervision intervention entailed additional training, resources and both administrative and supportive supervision, as outlined in a previous publication20. The intervention is based on the Mentor Mother program, founded and implemented by the Philani Maternal, Child Health and Nutrition program. The Philani program is a home-visiting intervention program for maternal and child health; it focuses on nutrition, HIV, alcohol, mental health, healthcare regimes, caregiving and accessing grants. Mentor mothers are CHWs recruited from the areas in which they live and are trained to deliver educational visits during the antenatal and postnatal period20,21. CHWs across both arms were trained by Philani; the CHWs from the enhanced-supervision clinics (intervention group) were subsequently supervised by Philani supervisors in addition to standard supervision as provided in the government-implemented CHW program. CHWs in the control arm of the cRCT were supervised by government-employed supervisors only. Two Philani supervisors were recruited to support 10 CHWs each. Supervisors had access to a car and a driver each day. Supervisors monitored home CHW visits every 2 weeks and monthly meetings with training and quality control were held in order to constantly improve the intervention. The study protocol details all processes20. The cRCT has recently been completed and the results are being analysed. Table 1 details the responsibilities in the two Eastern Cape Supervision Study conditions.

Table 1: Responsibilities in the two Eastern Cape Supervision Study conditions20

Sample

Stakeholders came from eight governmental clinics that were part of the Eastern Cape Supervision Study, with four clinics having received the enhanced-supervision program through the Eastern Cape Supervision Study with support from the local NGO Philani. The remaining four clinics ran the CHW program with no additional support. Stakeholders were in this case defined as key informants involved in the government-implemented CHW program in the study area and/or in the cRCT of which this qualitative report is a substudy. Stakeholders were involved on different levels; clinic personnel were either operational managers (clinic managers of the governmental primary healthcare clinics included in the cRCT) or outreach team leaders (government-employed CHW supervisors). cRCT supervisors were employed by the NGO responsible for the implementation of the supervision package. We recruited intervention supervisors (supervisors trained and employed by Philani to provide enhanced supervision), operational managers (nurses in charge of clinic operations) and outreach team leaders (nurses employed by the Eastern Cape Department of Health specifically to supervise CHWs), and intervention program managers. For this qualitative substudy, supervisors from both arms were interviewed to shed light on the status of supervision in the government-implemented CHW program and their experiences of the added supervision intervention. We focused on stakeholders from clinics involved in the cRCT and directly involved in the implementation of the CHW program in the field. For this study we interviewed nine government-employed CHW supervisors or clinic personnel, two cRCT program managers and two cRCT CHW supervisors. CHWs and clients have also been interviewed as part of this study; these data are reported on in separate articles. All CHWs were still employed and remunerated (in 2021 – approximately R3500 (A$190)) through the South African National Department of Health. We interviewed all program stakeholders (clinic personnel, supervisors and program managers from both intervention and control clinics) who were available for an interview and this reached participant saturation. In this case, we defined reaching participant saturation as when there were no additional stakeholders available to interview.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted from June to August 2021; both the intervention and data collection for the cRCT was then concluded. Individual interviews took place in a private space at either the health facility or a local training and research centre. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide focusing on the following topics: general implementation of the CHW program, supervision within the CHW program, and experiences of the added supervision intervention. Informed voluntary consent was obtained in the participants’ preferred language. All participants were assigned an identifying number, which was provided ahead of the interview. An isiXhosa and English-speaking research assistant with extensive qualitative experience conducted the interviews. The first author (LSK) and research assistant (NW) worked closely together to ensure quality of the data; each interview was discussed in detail immediately after it was conducted, and summary notes were written. Interviews were translated into English and transcribed by a separate team at Stellenbosch University who received de-identified audio recordings. Transcriptions and translations were checked for quality by a team of experienced research assistants at Stellenbosch University. Interviews with program managers were conducted in English by the first author given that English was their first language. Given the small pool of participants, and the fact that nine were employed by the Eastern Cape Department of Health, extra consideration was given to issues of confidentiality. In addition to participant identification numbers, names of clinics and all reference to geographical or contextual information were removed from transcripts to further de-identify the data. In any instance where identification might have been possible, we removed information. This de-identification was initially completed by LSK; any queries were resolved in discussion with MT.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used, structured by the six steps described by Braun and Clarke22: familiarization, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report. Transcribed interviews were reviewed line by line, and a preliminary coding scheme was developed. This coding scheme was then presented to members of the team to validate and discuss the identified themes23. ATLAS.ti software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development; http://atlasti.com) was used for coding, naming and organizing data. Once theme saturation had occurred, data extracts from each transcript were grouped together under each category24. In order to ensure objectivity and validate the analysis of the data, a second researcher (CAL) analysed randomly selected sections of data, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion22. Codes were collapsed into code groups and themes were derived.

Reflexivity

All authors had experience in qualitative and quantitative research relating to CHW programs in various settings. Previous research experience may have influenced the way the data were viewed; however, continuous discussions and data validation was done to mitigate this risk. We are aware that the first author (LSK), being a white woman with a privileged background, and not isiXhosa-speaking, may have affected the data collection and analysis process. The first author therefore worked closely with the interviewer (NW), going through every detail together.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Stellenbosch Health Research Ethics Board (N16/05/064), by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board (IRB 16-001362) and by the Eastern Cape Department of Health.

Results

Supervisors, operational managers, and outreach team leaders were all female; one program manager was female and one was male. Ages ranged from 32 to 59 years. All had worked in their current positions for at least 2 years at the time of the interview (time in current role ranged from 2 to 15 years).

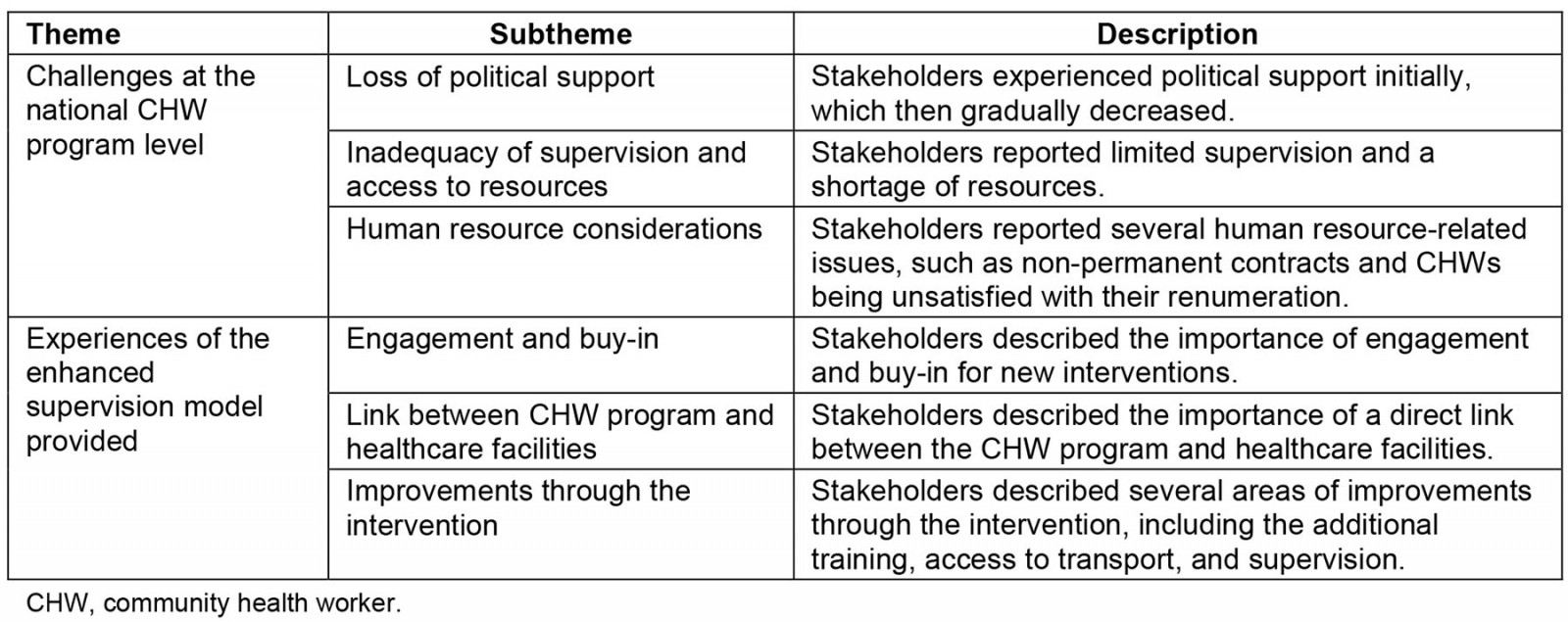

Two overarching themes and six subthemes emerged from our analysis (Table 2).

Table 2: Overview of themes

Challenges at the national CHW program level

Loss of political support: Program managers reported a clear shift in political support in the past decade, from strong buy-in for CHW programs to an increasing lack of support for the requisite resource and management needs. There was a sense that the governmental CHW program had lost support, both in terms of political will to administer these programs as well as in terms of funding:

My impression is that it’s a pendulum that has kind of swung from this is the solution to all in 2010/2011 when they [Department of Health representatives] came back from Brazil and the Department of Health wanted to get lots of people out to do lots of things … And then swinging towards that they realized they are hard work, we don’t know what they are doing, they are troublesome as they are striking, they are just causing us hassle and we don’t really want to make an effort to replace them. (Program manager 2)

This lack of political support filtered down into how the program functioned on the ground. As one program manager reported:

My impression is that there is very little support for them and therefore there is very little support for the CHWs so that they are demotivated and not that effective and many of them are actually not out in the field. So my sense is that we haven’t actually worked out a system, a structure that works. I am worried that even if they get paid little, 60 000 CHWs will be a big expense without a massive benefit for the health system. (Program manager 1)

Inadequacy of supervision and access to resources: In interviews with operational managers, it became apparent that supervision on a clinic level was problematic. In many of the clinics, the designated CHW supervisor (the operation team leader) was not working from the clinic to which they were attached, nor living in the catchment area. Instead, these supervisors were based in a mid-sized city approximately 1.5 hours from the clinics.

While operational managers reported that they tried to support CHWs, they had no capacity (time and resources) to be in the field. This gap resulted in what they described as a lack of real insight in the daily activities of CHWs in the field. They admitted not knowing much about CHWs’ caseloads, daily activities, or if they were in fact in the field at all:

Eish my sister, now that there are no people supervising them. I communicate with them only; I don’t see them for five days. I don’t even know if they went to those households, I am not sure. Sometimes on Fridays they won’t even find me here – like tomorrow I will be gone to do orders for medications. I won’t be around. I don’t even know if they found the clients or what is going on. … Personally I don’t even know which location they are working in now. (Operational manager 3)

Furthermore, there was a sense among stakeholders that CHWs operate largely in isolation, unable to access the support they needed to carry out their work effectively:

There is nobody knowing that you are going into the field and actually seeing people, there is no checking up if you... don’t create systems where people know that they will be checked upon, some people will abuse it. The second thing is that the support is also really poor, people feel that they are isolated, on their own, there is nobody who can give them advice, there is nobody who can tell them where the patient should go and that is what is so useful to have a link into the hospital. (Program manager 2)

There was a need for more equipment and logistical support (eg transport for CHWs) for CHWs to be able to carry out their work effectively. Operational managers and outreach team leaders reported that they did not have access to any equipment such as scales, stationery and equipment to measure blood pressure. In addition, without transport they struggled to visit clients at home, as the distances in the area were vast:

My community health workers don’t have the equipment to work now, even if they go to the households they would wish to take weight of clients and wish to do that and that and they cannot do those things. Their referral now is very poor because you would find out that the referral is just verbal … I wouldn’t even know if the client came to the clinic or not, you see? (Operational manager 1)

Human resource considerations: In addition, interviewees spoke about the need for permanent contracts for CHWs and better remuneration. During the course of the cRCT, several periods of strikes occurred, where CHWs did not work due to demands for permanent contracts and better salaries:

Currently the community healthcare workers are unable to work because they don’t have supervisors, they are not permanently employed, they don’t have tools and they can’t go where they want to go or where they are needed. … community health workers are uncertain of their employment and once you have job dissatisfaction you don’t get motivated or become productive because you don’t know where you fall under. (Operational clinic manager 3)

Stakeholders expressed concerns about the challenges in the government-implemented CHW program, and interviewees reported how the limited support had led to an ineffective program:

I think what is saw in practice was that if you are appointed to do a job that you are not equipped to do in any way, and you have zero support and no one is there to train you, especially if you are working in that kind of geographical area where I mean it’s so far removed from hospitals, from private doctors, there is just nothing – and all of a sudden you’re this person who has to help people but you don’t actually know how to help them at all, I mean it’s incredibly discouraging. (Program manager 2)

Experiences of the enhanced-supervision model provided

This section focuses on stakeholder perspectives on the implementation of the training and enhanced supervision intervention.

Engagement and buy-in: Although stakeholders noted some initial challenges and misunderstandings in terms of supervisor roles and reporting protocols, these challenges were described as having been overcome with time. There were initial concerns from the operational managers and outreach team leaders regarding the implementing NGO 'taking' their CHWs and thus removing them as a resource from the clinics, rather than providing extra support. However, this changed to over time, and clinic personnel reported being appreciative of the help offered by the additional supervisors, extra equipment and access to transport:

I tried getting some clarity on the purpose of the NGO teaming up with community health workers, on top of them getting paid and who is paying them. It has nothing to do with the money they get. What’s important is to do what has to be done to a person who is in the village, who is sick and needs help and who also wants help and how she can be helped only. (Operational manager 2)

Emerging from our interviews was the importance of a professional and quality approach to the recruitment of appropriate CHWs and then supporting them with continuous training and supervision:

You need strong stakeholders; you need strong CHWs. And we saw that, even in the intervention in different people. I can tell you which of the CHWs had benefited in getting this training and feeling like they had agency and really took up the challenge versus some people where it just didn’t make any difference to them and I always say … Where do they come from and what is it that makes them want to do it? I think a lot of our CHWs, the motivation for them was purely financial which I don’t think is enough in a job like this. (Program manager 2)

Link between CHW program and healthcare facilities: Respondents emphasized that it was essential for CHW programs to be properly anchored and embedded in the health system. The CHW program functions within the healthcare system, and interviews revealed that this embeddedness affected how the program could run. Two parallel issues emerged here; the first issue was that CHWs often were pulled into clinic work, as clinics were over-stretched and under-resourced:

I mean we saw that the clinic just didn’t have enough personnel so something that we found often was that the nurses in the clinics instead of sending the CHWs out in the community would just use them to do admin stuff or basic stuff in the clinics which is to my mind absolutely a signal of a larger problem. (Program manager 1)

Communication and referral lines within the program comprised a second issue relating to health system embeddedness. It appeared that the intervention facilitated clearer lines of communication, which enabled a stronger referral system:

I think there were a lot of the sisters at the clinics who would, you know, not necessarily have someone to call at the hospital. So it’s all this kind of disjointed system there which I think is very influenced by the geography as well. I mean it’s difficult to get from place to place there … Because that was also something that we found a way to do which CHWs could never do before. They had no kind of referral system and that was something that we could help them with … (Program manager 2)

Having a good link in to the hospital or even having a CHW liaison doctor per district hospital … if we have good-quality supervisor who can say, doctor this child is, I am worried about this child, what should I do? … It is good to have a broad overview of the services provided at the hospital, and then also to have a link in directly is very helpful. (Program manager 1)

A clear theme emerging from our interviews was the importance of tailoring the program design to the context:

So thinking more creatively about these kinds of things but that would ask of you to look at the different situations instead of trying to find a cover-all response in a country where even in our provinces it’s super diverse, and having a bit more ingenuity in terms of what does a specific context need rather than just say, well here everyone goes and we are going to try this all over. (Program manager 2)

Improvements through the intervention: Stakeholders emphasized the positive impact that the intervention’s new home-visiting model added. The package of training, supervision and practical support through equipment and transport appear to have had a substantial impact on CHW programming:

I saw that they came back very bright and refreshed. After that they noticed that they are being supervised and supported. They were even taught the skill of writing a report. (Operational manager 1)

During the time when there was NGO that was helping us with supervision for community health workers everything was going well and better because sometimes the supervisors would come with the case immediately – whether it’s an active case or not – they would come and report it or communicate it in terms of sharing and we would record it. Sometimes they would have already recorded the case and say ‘Sister we have this problem’ or better they would take it over and say that they are taking the client to [location]. (Operational manager 4)

Discussion

We explored the experiences of a range of stakeholders involved in implementing an enhanced supervision and support for CHWs employed by the Department of Health in rural South Africa. Clear issues with the current CHW system emerged, illustrating how CHWs were operating largely unsupported, with limited access to training, equipment and supervision. Respondents spoke of how the enhanced-supervision model introduced had mitigated these challenges.

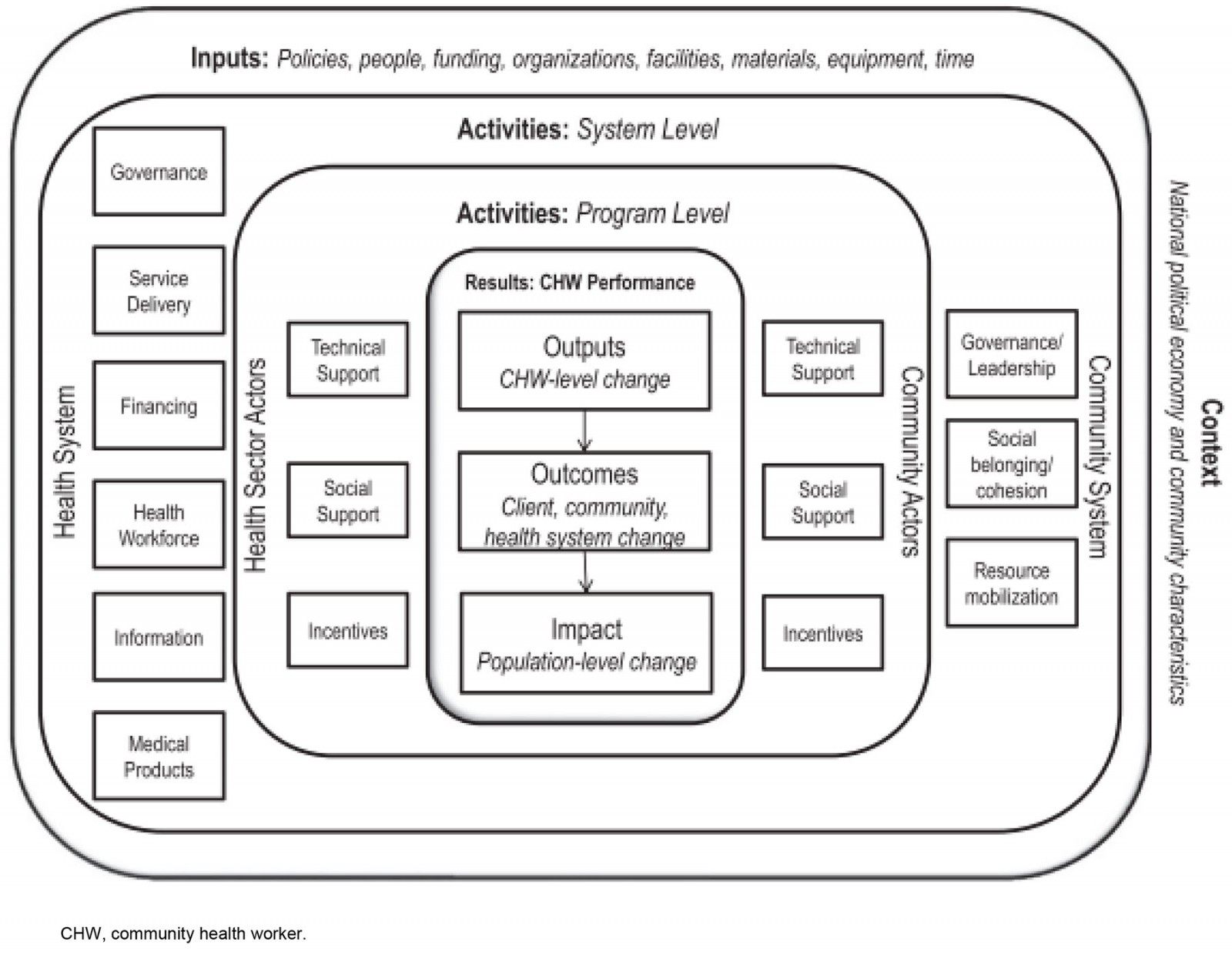

When considering the implications of these findings, the CHW generic logic model developed by Naimoli and colleagues25 provides a useful framework (Fig1). They have argued that CHW performance is primarily a function of supportive and high-quality CHW programming. It has been argued that due to the complex nature of CHW programs and their embeddedness in multiple systems (communities and health care), data regarding program performance should be gathered from a variety of sources – and, importantly, include contextual factors and enablers5. We take this framework and focus specifically on the context, the system level, and the program level. While this framework ultimately examines outcomes and impact on a community and population level, our endpoint in this substudy is CHW-level change as perceived by program stakeholders. We draw on this framework to organize our discussion in the different levels of systems that ultimately affect CHW performance and program functionality.

Within the national South African CHW program, investments and improvements at both the system level and the program level are essential. While the intervention in this study did not have the capacity to address system-level issues, program stakeholders reported a substantial impact on both an individual and a programmatic level through adding the intervention package, including supervision, training and equipment. As argued in a recent series on CHW programs1,26, these programs hold too much promise to not be invested in further. Lewin and colleagues describe the importance of support at multiple levels, including political and organizational support27,28. This take is closely aligned with the views of stakeholders in the rural Eastern Cape. Our findings echo the discussions in this series and other recent literature3, where support and embeddedness in the health system is critical and where domains such as recruitment, training, logistical support and supervision are where improvements are needed.

In the health system level of the CHW framework, where we have also included context and inputs, interviews revealed a perceived lack of political and governance support. While stakeholders recognized an initial political will and a sense of excitement for the CHW program, with time, stakeholders were uncertain if the South African CHW program had retained the required political support. The development of CHW programs in South Africa has largely followed global trends while adapting to the local social and political climate29. Due to concerns around the effectiveness of CHW programs, CHWs were not part of the primary healthcare approach initiated by the new African National Congress government in 1997. However, with the HIV epidemic, an urgent need for community-based care workers emerged, and CHWs were reinstated to support HIV patients30. As described in the introduction, in 2011, inspired by the CHW program in Brazil, the South African Department of Health invested in a new national CHW program resulting in the WBPHCOTs. While this model initially had substantial support and political will, the quality of program implementation has varied substantially between the different provinces, facing major challenges such as insufficient funding, poor governance and inadequate resources2,31. In certain provinces, CHWs are still organized and remunerated by NGOs contracted by the Department of Health, and in others employed directly by the Department of Health. It is concerning that the challenges facing national CHW programs were identified as early as in the 1980s4,32, yet appear to still remain4. A factor that may have contributed to the challenges in implementing the WBPHCOTs is health system preparedness – a key factor in successful CHW programming4. Our data suggest that the rapid implementation of the national CHW program in South Africa may not have happened within a health system that was ready for it31,33. With a health system that was, and still is, severely strained, fragmented and inequitable34, perhaps expectations on the revised CHW program were too high. Several of these shortfalls were reiterated by participants in this study and others in South Africa, including lack of supervision, access to equipment and transport, and dissatisfaction and confusion regarding contracts and remuneration35. These shortfalls act as individual and collective barriers to successful implementation28. Respondents recommended radical changes to the current program, including substantial improvements in training, supervision and access to equipment and transport. As Schneider and colleagues argue31, strong political leadership and a willingness to commit resources will be required for the WBPHCOT initiative to overcome its current challenges.

On the program level, our findings underline the importance of CHW and stakeholder buy-in for successful program implementation. Extensive engagement with stakeholders prior to implementation of a new system, making use of the principles of coproduction17 – or, at a bare minimum, substantial involvement of all stakeholders at the beginning phases of program design and implementation – is essential. The involvement of stakeholders is particularly important in a multifaceted program operating between the healthcare system and the community and where being context specific is critical36. One example of such involvement is the coproduced supportive supervision framework developed by Assegaai and colleagues17, where a framework for supportive supervision including several other program factors was coproduced with CHWs and other program stakeholders through a collaboration between university researchers and Department of Health. Furthermore, it has been established that conducive relationships between CHWs and other health professionals are critical for program success, and sufficient room and resources for these relationships to form need to be made a priority37.

Professional healthcare workers also stood out as a particularly important group of stakeholders. Having strong links between CHWs and/or supervisors and a healthcare professional at the local hospital (in this case, a doctor) is essential. CHWs or their supervisors could contact the doctor directly and medical advice could be provided; this link eased the management of serious and urgent cases. Although this may not be possible to replicate in other settings, it could be important to test the impact of designating one doctor for a CHW program in a given area. This part of this intervention is similar to the Brazilian Family Health Team model where each team includes a physician, a nurse, a nurse assistant and a variable number of CHWs2.

On the CHW level, the lack of a supportive system is evident, and it appears that the intervention in this study mitigated these challenges by creating a supportive system that improved CHW working conditions and thus their ability to carry out their work effectively. Training, access to transport, equipment and supervision played a major role in this. Although out of scope for this study, robust recruitment processes also emerged as a foundation for a successful program and others8. Recruitment is one of the key pillars in the Philani model38 and valuable lessons could be learnt from these processes, although recruitment was not a measured outcome.

The current CHW system needs major restructuring, shifting away from CHWs essentially operating in isolation, to one where CHWs are recruited systematically, provided with higher quality training, and given access to resources such as equipment and transport in order to perform their duties. Such a system would further ensure that CHWs receive supportive supervision that goes beyond simply administrative supervision.

CHWs have the potential to provide vital support in communities, but they need to operate in a functional supportive system1. It is clear that the governmental CHW program has many challenges – a number of which were temporarily mitigated by the intervention tested in the parent study of this research, in a collaboration between a local NGO and the Department of Health. These findings are promising, and stakeholders’ experiences of this intervention provide important lessons to take forward. Based on our findings in this study, we have developed a list of recommendations for practice.

Figure 1: Community health worker generic logic model25. This model illustrates factors determining CHW performance. Emphasis is on robust health and community systems creating a supporting framework on different levels for effective CHW programming.

Figure 1: Community health worker generic logic model25. This model illustrates factors determining CHW performance. Emphasis is on robust health and community systems creating a supporting framework on different levels for effective CHW programming.

Recommendations for practice

- Contracts and reimbursements are important for CHW motivation, and are essential prerequisites for CHW program success.

- High-quality training of CHWs is critical. Further investments in high-quality training should be made.

- Better access to equipment, for example scales and blood pressure machines, is needed.

- Access to transport is critical in rural areas to access remote locations.

- Supportive supervision is critical and can be provided through an intervention like the one presented here.

Limitations

It is important to note the limitations of this study. Stakeholders interviewed in this substudy were from a relatively small pool of partly Department of Health-employed stakeholders taking part in a larger trial in one province of South Africa. This may have caused concerns about confidentially; furthermore, it may have had an impact on the level of honesty in the interviews (eg reporting bias), particularly around critical feedback. We do not believe this was the case in this study, as various measures were put in place to ensure confidentiality, as described. Furthermore, the interviewer was not previously known to the stakeholders and was independent of the Eastern Cape Department of Health, which we believe was an advantage.

Conclusion

CHWs play a valuable role in the healthcare system, especially in rural low-resource areas. More resources need to be allocated to training, equipment and supportive supervision.

References

You might also be interested in:

2017 - Rural Health in Japan: past and future

2008 - They really do go