Introduction

Marginalised communities worldwide often face poor health outcomes1,2. These disparities are frequently rooted in historical disadvantages and challenging socioeconomic conditions. Among the most affected are the Narikuravar population of Tamil Nadu, India, who experience limited access to education and unstable income, further perpetuating these inequities. There is no publicly available data on the health status of this community, and no studies have yet been undertaken and published focused on their overall healthcare needs. India offers a range of free financial health access support programs and healthcare cards designed to enhance access to health care for underprivileged and marginalised people including the Narikuravar community. One national initiative is the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) government-sponsored health insurance scheme, which covers the hospitalisation costs of families living below the poverty line nationally. Within Tamil Nadu, families with an annual income under the poverty line can now also access the Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme (CMCHIS), which provides comprehensive medical coverage and cashless treatment facilities3. To access this, families first need to have an individual identity (Aadhaar) card (which has a unique 12-digit individual identification number issued by the Indian government), an income certificate issued by the Indian Revenue Service, a family card and a self-declaration from the head of the family3.

The name Narikuravar comes from the Tamil words nari, meaning ‘jackal’, and kuravar, meaning ‘wandering tribe’4. The Narikuravar community comprises 30,000 individuals, accounting for 0.1% of the Tamil Nadu state’s total population of 76 million5. The majority of the Narikuravar population traditionally lead a nomadic lifestyle, frequently moving their camps from one location to another6. Their different and fascinating way of life is often demonstrated by their unique dusty appearance. Their distinctive clothing, characterised by vibrant colours, sets them apart from the rest of society. For many decades, they have engaged in traditional practices such as hunting, gathering, fortune-telling and bead-selling, which have been passed down through generations. Narikuravar communities maintain strong ties to their cultural heritage, and they preserve unique customs, language and spiritual beliefs. Their discrete culture and separation from the mainstream community have contributed to their exclusion from the general population7. This marginalisation is a barrier to receiving basic healthcare services.

Narikuravar people living in Poonjeri

The Chettinad Academy of Research and Education university hospital provides extended rural primary health services and health camps. A small village called Poonjeri, situated in Lathur Block under Seekanankuppam Panchayath in Kanchipuram District in the state of Tamil Nadu5, is one of the adopted villages of this program. Poonjeri village has a population of 1890 people and on one of our visits the lead researcher and two nursing students discovered that there were Narikuravar families living on the outskirts of the village. Each Narikuravar family had six to eight members living in communal housing in a single-room house with their own piece of land, provided by the state government. Of the 81 houses, only 24 houses situated on three streets had access to common latrine facilities, which were built at the end of each street. Other households were practising open-air toileting. In every house there was an LED TV, fan and grinder (blender) provided by the government. Residents live a communal life – cooking, conversing in groups and watching television, with children playing on the roads.

The nursing team initiated a project focused on the healthcare needs and access challenges for the Narikuravar people living in Poonjeri.

Methods

A mixed-methods research design underpinned by realistic theory was conducted over a period of 18 months (January 2023 – July 2024) to establish a deeper understanding of the Narikuravar community’s healthcare access and health-related encounters8.

The research was undertaken by the head of the nursing college (female nurse researcher) and two nursing students (one male and one female) in consultation with the local Narikuravar people. They first built a trust relationship with community members. They met with the community elder, the leader of the Narikuravar community, and obtained his consent for this project. He designated one community member to be the community representative throughout the research, and this man is also a co-author of this article. During our discussions, community members shared that many health organisations visited them at their locality through healthcare camps. However, after a period of time assessing the Narikuravar community’s health conditions, the healthcare workers would end the camps, leaving the community with no hands-on follow-up treatments or medicines. This raised concerns for the researchers, prompting us to both provide health services and an exploration into local Narikuravar people’s access to ongoing health care. We began basic community health-nursing home visits, health education, screening (including immunisation and blood pressure checks), maternal and child health services, and engaged in disease-prevention activities including vector control to reduce infectious diseases. While providing these services, and talking with community members, we gained a community-specific, nuanced understanding of how regional identity and societal positioning influenced their access to healthcare services.

The principal nurse researcher designed data collection tools with the students with feedback from the elder, community representative and community members. A structured questionnaire was designed to identify demographic characteristics, health-seeking behaviour and the availability of government-issued healthcare cards needed to access health care; and semi-structured qualitative interviews included prompt questions to deepen understanding of community member experiences and understanding of accessing health care. The students pilot-tested the survey and interview questions in another Narikuravar community.

Following the elder’s permission and ethics approval, both quantitative and qualitative data was collected from 81 Narikuravar individuals using the snowball technique and introductions by the community representative. Purposive sampling was used to ensure a wide range of experiences in accessing and utilising health services across both genders and a range of ages 18 years and over8. Interviews took place in community spaces, at home and under trees – wherever the community member preferred, and often with other community members nearby. Participants answered survey questions and then prompt questions, with each interview between 45 and 60 minutes. Recruitment ceased after 81 interviews with data saturation.

A consent form was co-created as an easy-to-read format. For those who were unable to read Tamil, the form was read and explained, with participants invited to sign using a thumb print. Those who were able to read and write Tamil read the participant information sheet and signed the consent form. Initially, the majority of the community were reluctant to interact with the team in the research. There were no refusals, however. Many potential participants expressed fear, and some were unwilling to disclose their personal information such as phone number and address. An agreement was made that their private details would remain anonymous and confidential, and would be accessible only to the principal nurse researcher.

The quantitative data was analysed by the nurse researcher and students using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v26 (IBM Corp; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) and descriptive statistics. Qualitative data was audio-recorded and transcribed by the students, then cross-verified with the participants alongside the quantitative data, to ensure researchers fully understood the meaning and context of results. Field notes were also taken. Content analysis using both deductive and inductive approaches was undertaken by the nurse researcher and students9.

Ethics approval

This study received approval from the Chettinad Academy of Research and Education Institutional Human Ethics Committee (IHEC-l/1684/23).

Results

Data were collected from 81 Narikuravar community people in the village of Poonjeri, as shown in Table 1. Nearly equal numbers of males (M, 42.5%) and females (F, 57.5%) participated in this study.

For each of the following quotes recorded during interviews, multiple participants are attributed because they were sitting together in a group, and all group members contributed to the statement and agreed with or reiterated the statement. The preference of this community is that these quotes are seen as a collective statement rather than an individual statement.

The Narikuravar people stressed the importance of their culture, which included marriage at a young age:

Our cultural practices are inevitable, we get married within 13 to 15 years [of age]. (M37, F22)

Of the 81 participants, 16 (20%) married as children between the ages of 13–15 years, 41 (51%) were married between the ages of 16 to 18 years, and 23 (29%) were married between the ages of 19 and 21 years. Most lived with four to seven family members in communal housing. Their levels of formal education level were low: almost three-quarters of the community (73%) had not attended school, 18% had only primary education and the ability to read and write, and very few (9%) had secondary education. The prime occupation was making bead ornaments and handcrafted jewellery (55%). Participants reported extremely low wages, with many earning 1000 to 3000 rupees (approx. A$17 to A$51) per month (61%). None of the people surveyed begged for money on the streets. Nearly half (47%) identified as Christian; others were Muslim (37%) and Hindu (16%). Around 23% of those surveyed relied on shared latrines for sanitation purposes and many (65%) had no access to toilets, practising open-air defecation. Most participants used public transport (56%), nearly a quarter had bicycles (26%) and most others walked (14%). Three people (4%) had a motorbike. Alcohol use (52%) and smoking (38%) levels were high, and a tenth of those participating used narcotics (10%).

When asked about their healthcare-seeking behaviour, the Narikuravar people reported that sociocultural language barriers and stigma influenced their reaching out to health services, with 83% reporting that no culturally appropriate service was available or delivered. Participants reported that healthcare workers were not culturally sensitive:

Hospital staff treated us from the Narikuravar community the same like others but no one knows about our culture, we wish our culture is respected. (F46, M17)

Travelling to healthcare facilities outside of the village was often challenging for participants. One person discussed needing to walk 2 km to seek health care while very unwell.

Over half of participants (54%) had visited the nearby hospital in the previous 6 months, just over a quarter had utilised the pharmacy (28%) and a few had sought traditional healers (4%) for minor ailments. Most (58%) had previously utilised hospitals for emergency treatment and surgeries. There was 100% attendance for child and maternal immunisation, but no uptake of COVID-19 vaccination due to their beliefs and concerns regarding the newly developed vaccination10. To our knowledge, this is a new finding not reported in any other study. Levels of alcohol and drug use among the Narikuravar people was not considered by those interviewed to be a significant problem, and no participants had sought mental health or drug-alcohol services.

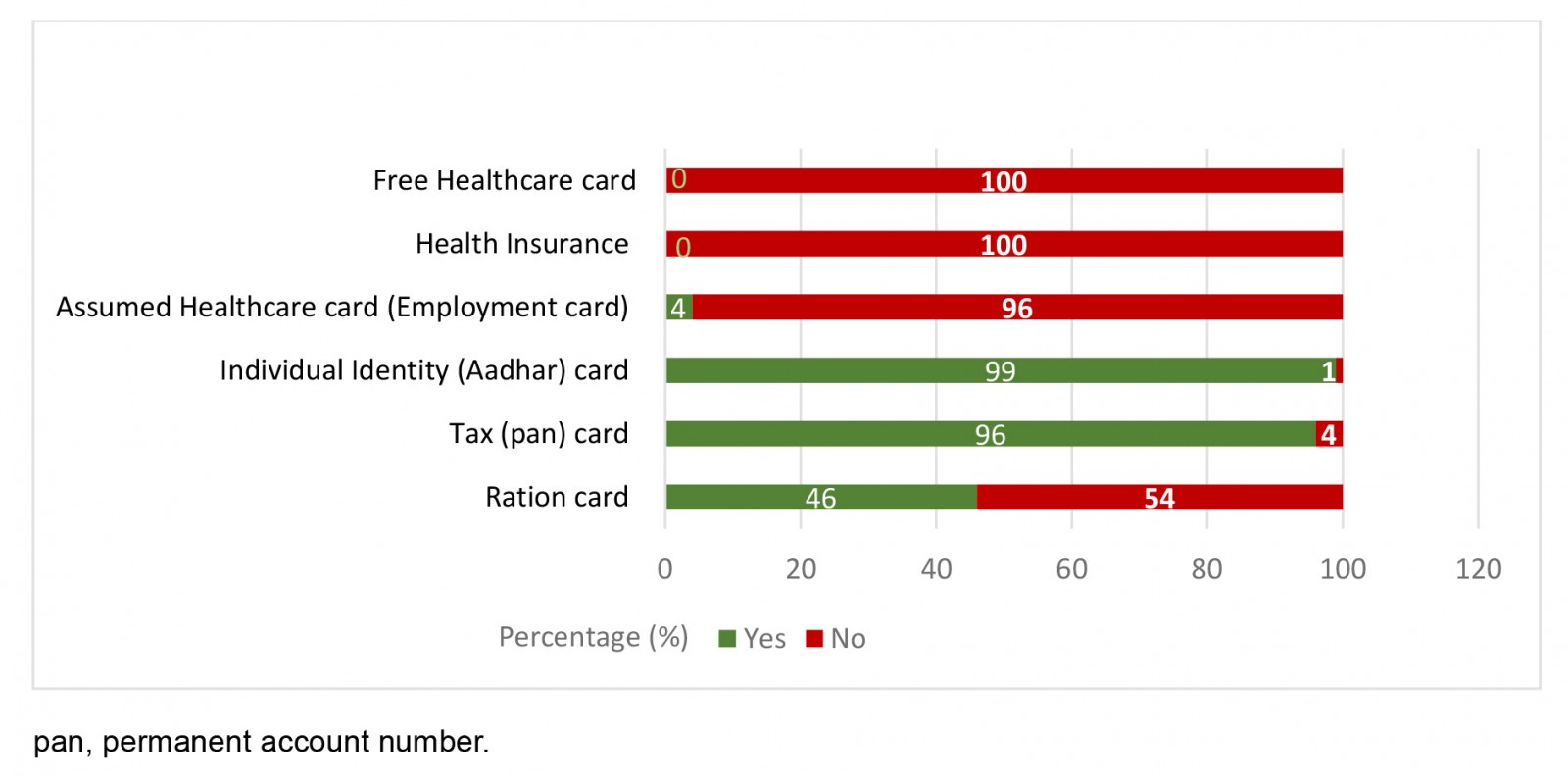

An unexpected and shocking revelation was that none of the Narikuravar people interviewed possessed a free healthcare card (100%) for either the national (RSBY) or regional (CMCHIS) health insurance scheme. Those interviewed were not aware of the availability of healthcare cards and had no knowledge of the online application process needed to receive them. Many had been given tax (PAN or permanent account number) cards regardless of their extremely low income, and they showed us these cards believing that they were the free government healthcare cards. We invited all participants to show us the cards they had received and then collated them in Figure 1 to provide a clearer overall picture. Nearly half of participants held a ration card to help with daily living expenses.

The reduced reach and effectiveness of government initiatives for this significantly disadvantaged community became even more apparent as people explained their understanding of the cards issued to them:

This is the healthcare card that I own for free medical treatment [showing the employment card that was safely kept in their pouch]. (M01, F21, M17, M33)

We do go to hospital when we are sick, but we don’t know about the health insurance and any privileges given by the government. Few of us have healthcare cards, and we do not know how to use them. (F72, M80, F1)

Although members of the Narikuravar community are the most eligible and prioritised population nationally for receiving free healthcare cards to assist them to access healthcare funding support, none of those interviewed had the free national RSBY healthcare card or regional CMCHIS health insurance card.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics and health-seeking behaviours of Gypsy (Narikuravar) people, Tamil Nadu, India (N=81)

| Characteristic | Variable | n | % | Health-seeking behaviour (n) | χ2 | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | Pharmacy (chemist) | Traditional healer | Home remedy | Did not use | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 34 | 42.5 | 15 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 4.628 | 0.201 |

| Female |

46 |

57.5 | 28 | 13 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |||

| Age at marriage | 13–15 | 16 | 20 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.849 | 0.093 |

| 16–18 |

41 |

51 | 20 | 14 | 1 | 6 | 0 | |||

| 19–21 |

23 |

29 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 0 | |||

| Members per family | 2 or 3 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3.869 | 0.920 |

| 4 or 5 |

35 |

44 | 19 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 0 | |||

| 6 or 7 |

30 |

38 | 15 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 0 | |||

| >7 |

7 |

9 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Education | No formal education | 58 | 73 | 3 | 16 | 32 | 7 | 0 | 3.760 | 0.926 |

| Primary education |

15 |

18 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Secondary education |

7 |

9 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Graduate |

0 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Employment | Shell ornaments | 44 | 55 | 29 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 9.549 | 0.145 |

| Matchbox making |

23 |

29 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 | |||

| Begging |

0 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Industries |

13 |

16 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Monthly income (rupees) | <1000 | 19 | 24 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0.166 | 0.983 |

| 1000–3000 |

49 |

61 | 24 | 13 | 7 | 5 | 0 | |||

| 4000–6000 |

12 |

15 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 7000–10,000 |

0 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Religion | Christian | 38 | 47 | 24 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 7.620 | 0.267 |

| Muslim |

30 |

37 | 15 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 0 | |||

| Hindu |

12 |

16 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Toilet | Public | 18 | 23 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4.893 | 0.559 |

| In-house |

10 |

13 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Open-air |

52 |

65 | 30 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 0 | |||

| Transport | Walk | 11 | 14 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.697 | 0.669 |

| Bicycle |

21 |

26 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |||

| Motorbike |

3 |

4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Public transport |

45 |

56 | 23 | 13 | 1 | 8 | 0 | |||

| Drug use | Smoking | 30 | 38 | 18 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2.490 | 0.873 |

| Alcohol |

42 |

52 | 22 | 11 | 2 | 7 | 0 | |||

| Other drugs (narcotics) |

8 |

10 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||

1.00AUD ≈ INR55.42

Figure 1:Government cards possessed by the Gypsy (Narikuravar) individuals of Tamil Nadu, India.

Figure 1:Government cards possessed by the Gypsy (Narikuravar) individuals of Tamil Nadu, India.

Discussion

Our project with the Narikuravar people living in Poonjeri focused on helping provide basic visiting health services including vaccination and exploring their ongoing healthcare access challenges. Several studies have identified the marginalisation of Traveller/GypsyRoma people internationally2,8,11-14, and two have previously identified healthcare access challenges for Narikuravar communities related to low levels of education, reduced access to healthcare cards, and significant stigma and discrimination when accessing care15,16. Our study was specifically designed with the Narikuravar community in Poonjeri to provide an insight into the significant obstacles they encounter when trying to access ongoing healthcare services. Unlike a study undertaken in 2017, we found that the Narikuravar people did not understand the card system needed to access healthcare services. We found the combination of undertaking both a survey and interviews, and talking with community members and the elder over time, enabled us to gain a deeper understanding of the situation for Narikuravar people living in Poonjeri.

We identified that despite the implementation of government programs, including the RSBY and the CMCHIS3, the Narikuravar community in Poonjeri continues to experience significant obstacles to accessing timely and quality health care4. This is further exacerbated by the majority of the community receiving very little formal education17, experiencing low income, and being unfamiliar with health insurance and government healthcare privileges and card processes. This highlights the importance of health education programs and health care that are accessible, affordable, understandable and tailored to meet the unique requirements and literacy level of marginalised communities.

Arguably, the Narikuravar community in Poonjeri are some of the most marginalised and disadvantaged when it comes to accessing health care. The majority of participants face extreme financial constraints (61.2% are on the lowest income of 1000 to 3000 rupees), and allocating funds for healthcare expenditure was a significant challenge. They primarily spent their income on daily living expenses, and nearly half relied on ration cards. The need for robust monitoring and accountability mechanisms to ensure the effective implementation of government healthcare initiatives, and to prevent exploitation of vulnerable populations, as expressed by WHO18, is clear.

It was quite shocking to find that Gypsy (Narikuravar) people lacked general awareness of the financial support for healthcare access that is available to them; that they encountered significant sociocultural and language obstacles, which impacted their health-seeking behaviour; that some experienced feelings of exclusion and discrimination arising from healthcare providers’ attitudes and behaviour toward them; and that needed healthcare facilities and services were often inaccessible due to geographical distance and lack of transport. Walking 2 km to nearby healthcare services (as participants said they did) may not be possible depending on their health issues. The significance of this lack of accessibility is that it raises yet another obstacle in the way this marginalised community receives the health care they need4,16,19.

Our findings emphasise the absolute necessity for greater cultural competence among healthcare workers, which can be achieved through providing cultural sensitivity training for all healthcare professionals to improve the provision of responsive and considerate treatment for every patient, regardless and mindful of their cultural background, as identified by previous studies7. The findings also emphasise the significance of geographical accessibility of healthcare institutions and the difficulties for the study population in reaching facilities further than 2 km from their village20. There is also a need to coordinate infrastructure and transportation networks to enable distant and underprivileged groups to more easily access healthcare services.

There are clear indications of what could be done to increase the use and accessibility of healthcare for the Narikuravar and similar population groups12,21-24. First is ensuring that information regarding health services and access support is adequately communicated so that more people are aware of, and can access, services. Specific strategies may include:

- using the media to spread information about health services and the value of such services, because it is evident through the survey that 61% of families have television at home

- educational initiatives to improve children's literacy skills

- implementing improved healthcare delivery in rural areas and other places where it is deficient

- building more effective, more relevant policies that are intended to affect the livelihoods of this Narikuravar population.

This project has identified the diminished efficacy of government organisations and initiatives to create a general awareness of available health insurance and financial support for healthcare access, and it reinforces the need for adequate and tailored community education strategies for disadvantaged communities.

Study limitations and strengths

This study was conducted among Narikuravar individuals who spoke a local Tamil language. Steps were taken to ensure the study was accessible to those unable to read. This study was purposefully focused on the experiences of the Narikuravar people from Poonjeri village and sought to gain a contextualised understanding of access barriers to health care. While specific details of results pertain specifically to this community and location, the underlying concepts impacting access can be considered and investigated with other community populations and settings.

Conclusion

The study has identified and emphasised the complex interplay of socioeconomic, cultural and systemic factors contributing to the healthcare disparities faced by the Narikuravar community. Addressing these disparities requires a multifaceted approach that includes targeted health education, cultural sensitivity training for healthcare providers, improved infrastructure and transportation networks, provision of government healthcare cards to those who are eligible, and rigorous monitoring of healthcare initiatives to ensure equitable access for all. Only through collaboration between on-the-ground Narikuravar people and government agencies, healthcare providers and community stakeholders can meaningful progress be made towards achieving health equity for marginalised populations including the Narikuravar community.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the marginalised Australian Aboriginal people with whom the principal author worked and was mentored by, and who paved the way for her to better understand and work with local Narikuravar people in Tamil Nadu, India. We acknowledge the Narikuravar people living in the locality of Poonjeri for their active participation in the study, and the nursing students who undertook data collection. Thanks to Margaret Bowden, Em Bee’s Editing, for editorial assistance.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

You might also be interested in:

2014 - Gender and age are associated with healthy food purchases via grocery voucher redemption

2005 - The quality of procedural rural medical practice in Australia