full article:

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus and social disadvantage are related; that is, when people live in disadvantaged situations, they are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes1. In Australia, this association is highest among Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples). Indigenous Australians have type 2 diabetes rates 3–6 times higher than that of non-Indigenous Australians, and are among the most socially disadvantaged in the country2-4.

Social disadvantage is an accumulation of suboptimal social determinants of health (SDoH), which include income, employment, housing, education, transport, social support and access to health care5. For Indigenous Australians, social determinants also combine with cultural determinants to influence health. Cultural determinants include culture, spirituality, family and connection to traditional land2,4,6.

SDoH are typically addressed at a population level, with the aim of achieving sustained health equity, social justice and generational improvement of people’s lives5,7,8. While the necessity of a population approach is difficult to contest, people’s immediate, idiosyncratic health needs must also be addressed. The connection between SDoH and the increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes suggests simultaneous consideration of SDoH and type 2 diabetes, at individual and clinical levels, may be beneficial. Addressing the direct relationship between poor SDoH and type 2 diabetes management9 warrants investigation, particularly in an Indigenous Australian context.

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians with type 2 diabetes are expected to understand the disease and achieve management goals10. Effective diabetes management often involves substantial lifestyle adjustment, which can be an impossible task for people with poor SDoH. The combined challenge of lifestyle change and poor SDoH could be reduced for Indigenous Australians if the intricacies of culture, ‘spirit’, family and connection to land2 were incorporated into type 2 diabetes care.

Routinely considering SDoH when providing type 2 diabetes care, and understanding how these affect an Indigenous person’s way of life, could help health professionals and other service providers develop more contextualised interventions. Subsequently, identifying and addressing the associated self-management barriers could assist Indigenous Australians in achieving their type 2 diabetes management goals.

To date, clear guidance on how to include SDoH into clinical health management has been scarce, which may stem from an overall deficit in organisational level guidance, such as policies and procedures for taking action on SDoH in healthcare settings11. However, multinational momentum towards screening for and addressing SDoH issues in clinical healthcare settings has begun12-18. These approaches could provide helpful guidance on how to incorporate SDoH into the clinical management of type 2 diabetes. In addition, it is imperative that the perspectives of Indigenous people are considered. Specific to this study is the perspective of Indigenous Australians.

The purpose of this article is to report the viewpoints of Indigenous health professionals who work with people with type 2 diabetes (IHWs) and Indigenous Australians with type 2 diabetes (Indigenous Australians with diabetes) on how the SDoH of Indigenous Australians can be incorporated into the clinical management of type 2 diabetes.

This study aimed to draw on the combined perspectives of Indigenous Australians with diabetes and IHWs to explore:

- the SDoH-related self-management barriers and facilitators to managing type 2 diabetes, from an Indigenous Australian perspective

- strategies to incorporate SDoH into the usual clinical care for Indigenous Australians with diabetes.

Methods

Design

This qualitative study used an exploratory, descriptive approach19 to combine the insights of Indigenous Australians with diabetes and IHWs. The intent was to increase understanding on how the social determinants affect Indigenous health, and the self-management of type 2 diabetes, and ways SDoH can be incorporated into the usual clinical care for Indigenous Australians. The six core values of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines for conducting research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities were integral to the research design. The core values are spirit and integrity, cultural continuity, equity, reciprocity, respect, and responsibility20. Fidelity to the guidelines was assured through the guidance of cultural advisors, cultural mentors and cultural brokers, and is documented throughout this paper.

Situating the researcher

The primary researcher (AF) is a non-Indigenous, female diabetes educator and dietitian. For approximately 5 years she lived and worked in remote Indigenous communities throughout North and Western Queensland, Australia. Currently she resides in a regional city of North Queensland and works collaboratively with IHWs who provide outreach health services to rural and remote communities. Being witness to the SDoH-related challenges some Indigenous Australians with diabetes endure stimulated her motivation to investigate this topic. To avoid misinterpretation of the data, a reflexive mindset was adopted, whereby self-reflection and self-awareness of personal context and experiences were maintained throughout all stages of the research project21. Furthermore, to enhance cultural appropriateness, she consulted regularly with cultural advisors and cultural mentors, and worked with cultural brokers on all aspects of the project.

Setting

Two health services, both with offices in Cairns and Townsville (North Queensland), participated in the study. One is a government service, the other a not-for-profit organisation. Both services provide diabetes care to regional, rural and remote Indigenous communities within their service districts as part of their regular service provision (seven communities in total). They are not community-controlled health services; however, they prioritise the needs of Indigenous Australians by including IHWs on the team, providing regular outreach services to Indigenous communities, and working with local Indigenous services and agencies.

Data were collected through small yarning circles and individual interviews. AF conducted all interviews and yarning circles. In accordance with cultural guidance, Indigenous Australians with diabetes only participated when an IHW was present, or if the IHW ascertained that they were comfortable, and the circumstances were appropriate for autonomous participation. Consequently, to ensure culturally safe voluntary participation, it was necessary for AF to join the IHWs (ZC and RR) on their scheduled community visits.

The interviews and yarning circles were conducted in locations where participants felt most comfortable. The locations included meeting rooms, waiting rooms, outdoor grassed areas and private residences.

Participant recruitment

A non-probability, purposive sampling approach19 was adopted. This was to ensure all participants were IHWs who worked with people who have type 2 diabetes, or Indigenous Australians with diabetes. Study details were provided to all participants in written form. Attention was paid to participant literacy level (particularly Indigenous Australians with diabetes); consequently, a detailed verbal explanation was also provided to ensure full cognizance of the study. In total, 14 people participated in the study (seven Indigenous Australians with diabetes and seven IHWs). All study participants were over 18 years of age. Written consent was attained prior to participation. Before providing consent, AF read the consent form to participants, and provided a verbal explanation (if desired).

Indigenous Australians with diabetes: AF was a member of the clinical staff in one of the participating organisations. To avoid influence, and to increase the trustworthiness of the study19, three colleagues (two IHWs and one non-Indigenous diabetes educator) recruited all Indigenous Australians with diabetes in a face-to-face manner, independent of AF. After each individual agreed to participate, the IHWs personally introduced the Indigenous Australians with diabetes to AF prior to participation in the yarning circles or interviews.

Indigenous health workers: Also to minimise influence, IHWs from the same organisation as AF were informed about the project and invited to participate through their supervisor, with emphasis placed on the voluntary nature of participation. IHWs from both organisations were then invited to participate in the study via email, which was followed up by a verbal invitation (between 2 days and 1 month post-email).

Data collection

Study participants were offered the choice of taking part in a yarning circle or a one-on-one interview. Demographic information, duration of diagnosis and IHW title and qualifications were collected in a short questionnaire completed prior to the yarning circles/interviews. This was collected to reflect the variety of genders, age, years of type 2 diabetes diagnosis, and level of IHW experience and qualifications. There were no specific requirements for yarning circles to consist of IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes separately; rather, natural formation of the groups was preferred because the aim of the study was to analyse the combined perspectives of IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes.

Yarning was the most appropriate method of data collection because it enables participants to tell their stories, in their voices, based on their lived experience22. By incorporating aspects of clinical yarning23, the stories of Indigenous Australians became a vehicle to understanding their experience of type 2 diabetes. Combining traditional yarning with aspects of clinical yarning allowed for the necessary clinical information about type 2 diabetes and SDoH to be elicited in a culturally congruent manner22,23.

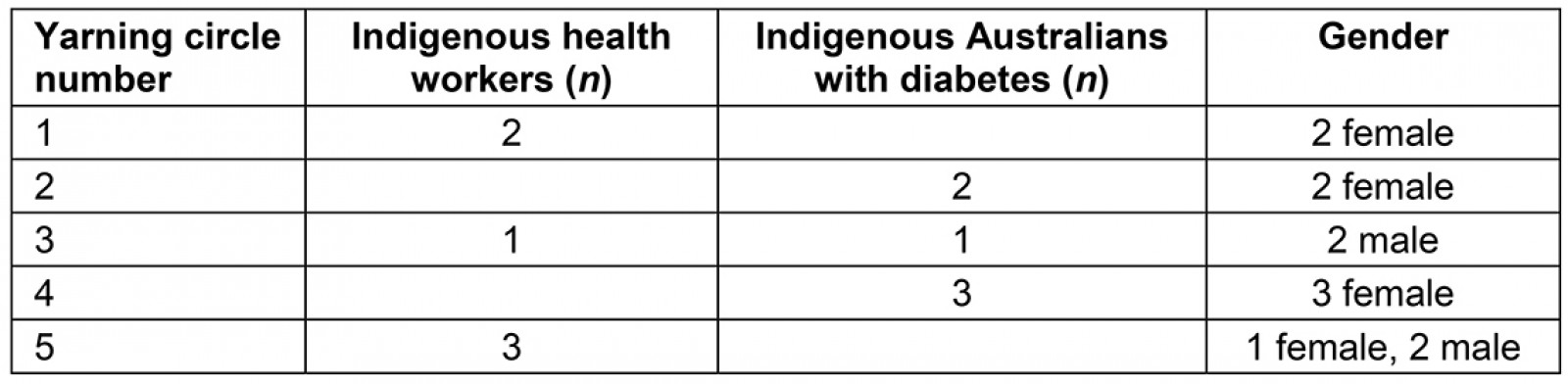

Two one-on-one interviews (one female IHW, one male Indigenous Australian with diabetes) and five small yarning circles (n=2, n=2, n=2, n=3, n=3) were conducted (see Table 1 participant details). Only one yarning circle (n=3) was of mixed gender. This was a group of IHWs who felt comfortable participating in this manner. Gender differences between AF and all participants were discussed (prior to interview/yarning circle) with an IHW (ZC or RR), who acted as cultural broker. One yarning circle of female Indigenous Australians with diabetes (n=2) was co-facilitated by an IHW because it was decided her presence would create a more culturally safe and comfortable environment. To enable consistency in data collection, AF conducted all interviews and yarning circles. With consent, all interviews and yarning circles were audio-recorded for future transcription.

Table 1: Yarning circle participant details

Data analysis

Data analysis was guided by the six steps for thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke24: data familiarisation, initial coding, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and renaming themes, and producing the report.

AF transcribed all audio recordings, which allowed for more accurate transcription and for data analysis to develop and deepen reliably. Rigour of the study was increased by a sample of these transcripts being reviewed by the second researcher (SD). The initial appraisal was to review the relevance of the questions asked, and to commence independent identification of emerging themes.

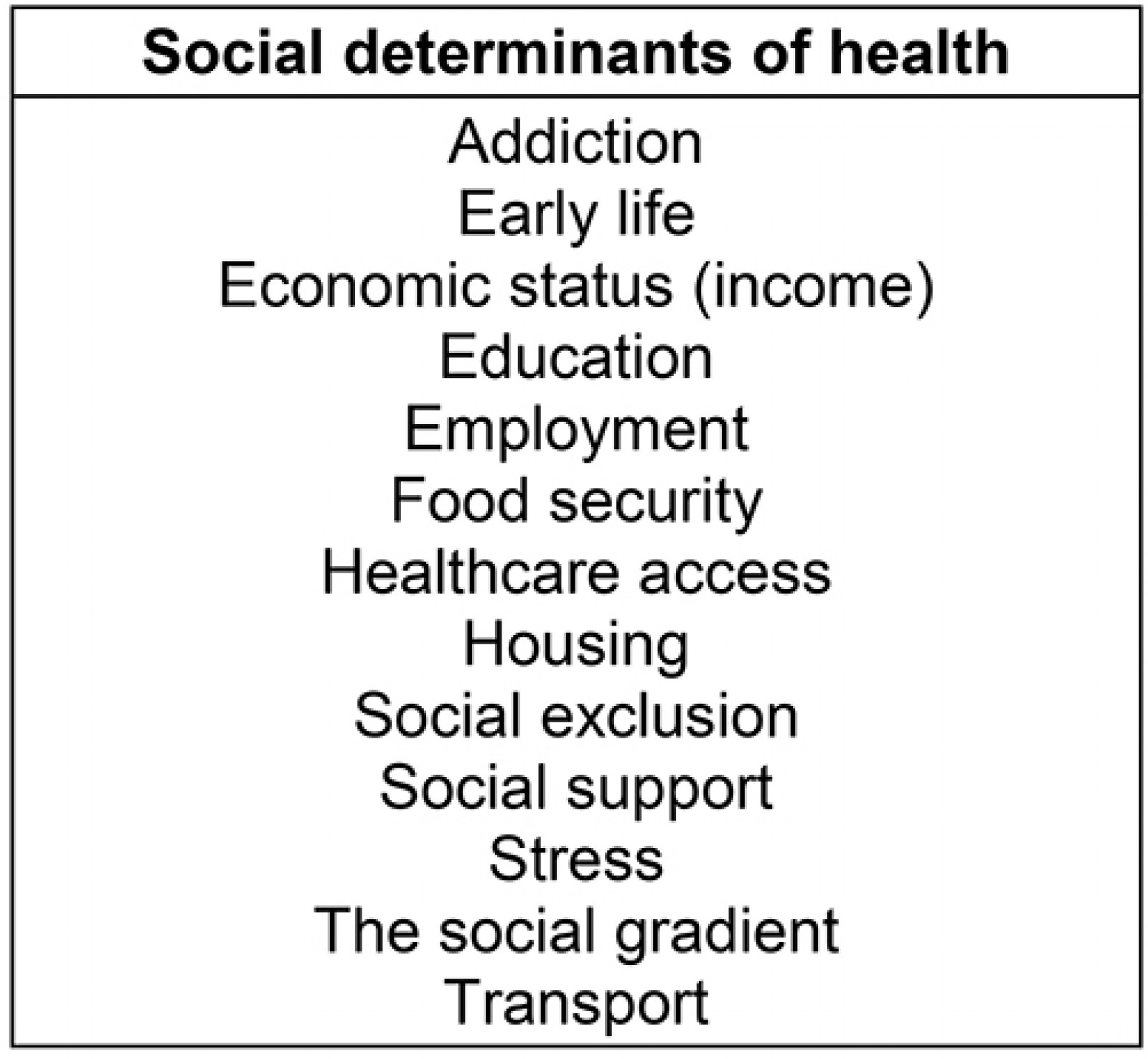

Transcripts were imported into NVivo v12 (QSR International; http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo) for thematic analysis19. A combination of deductive and inductive data analysis was applied during initial coding, which enabled simultaneous targeted exploration into SDoH issues, and open exploration of participant perspectives25. The theoretical framework used for the deductive analysis was based on well-known SDoH5 (see Box 1). A deductive approach was incorporated to identify examples of how SDoH can affect the ability of Indigenous Australians with diabetes to self-manage their type 2 diabetes. The inductive analyses and a phenomenological approach enabled deep exploration of participant experiences19 of type 2 diabetes through an SDoH lens.

Triangulation continued throughout the analysis phase with regular analytical discussions on coding and theme development between AF and SD. The third researcher (KMR) reviewed the initial codes (established by AF and SD) and concurred with their accuracy. After minor modifications and clarification of terminology, all three researchers agreed on the final themes.

Following final theme consensus, member checking was completed with five of the seven IHWs (two were not contactable). The identified themes were discussed and explained to confirm the accuracy of interpretation and subsequent findings. The Indigenous Australians with diabetes were not contactable because of the transient nature of their lifestyles. Consequently, the IHWs (ZC and RR) who organised recruitment and assisted with facilitating a yarning circle confirmed the accuracy and incorporation of the responses.

Box 1: SDoH framework used for deductive analysis.

Box 1: SDoH framework used for deductive analysis.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Queensland Health (HREC/18/QTHS/128) and James Cook University (H7480). Importantly, this approval requires demonstrated adherence to the NHMRC ‘Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders’20.

Results

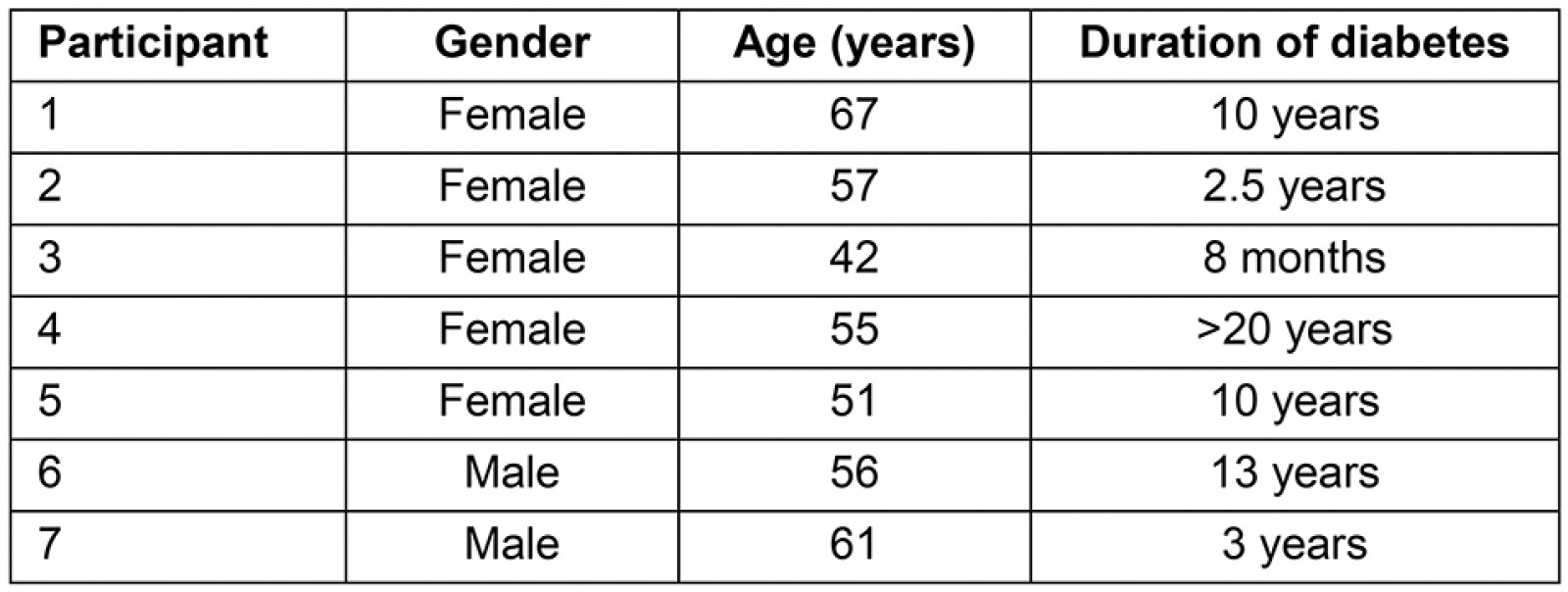

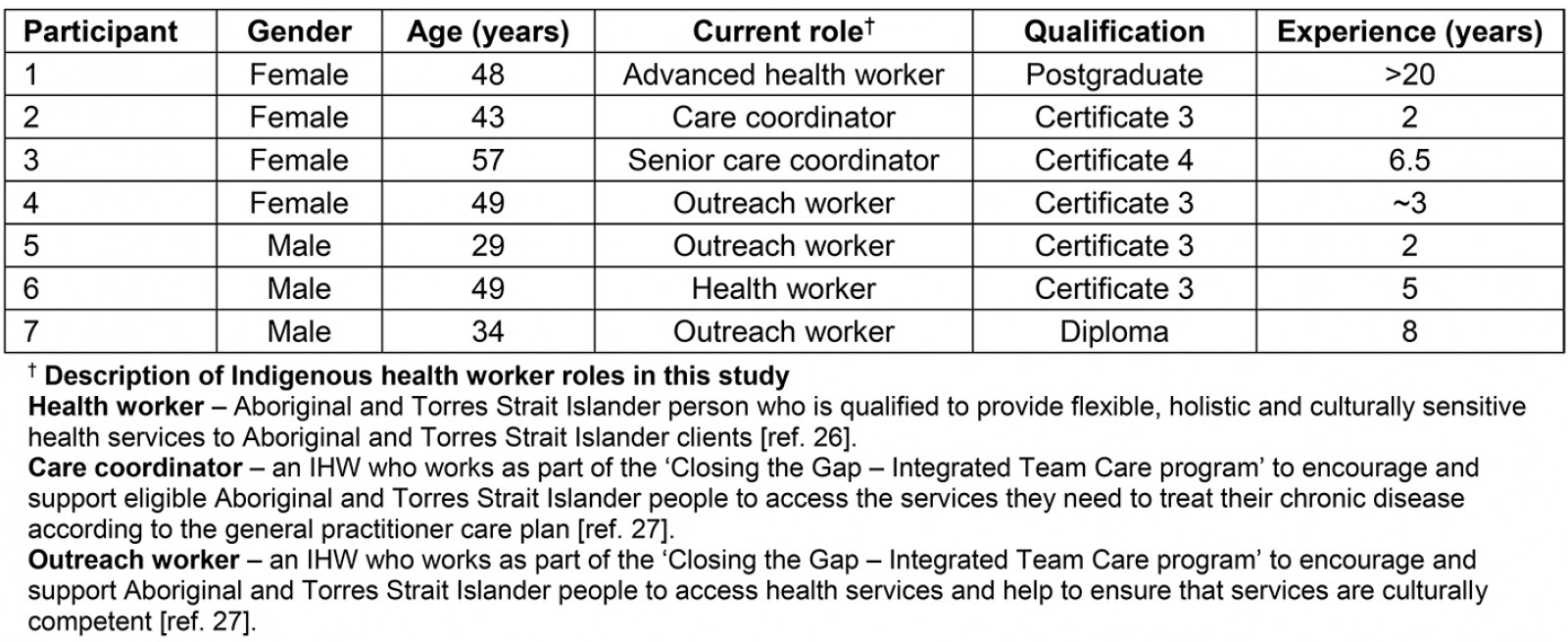

Fourteen Indigenous Australians participated in the study. Seven participants were Indigenous Australians with diabetes and seven were IHWs. Participant characteristics are outlined in Tables 2 and 3.

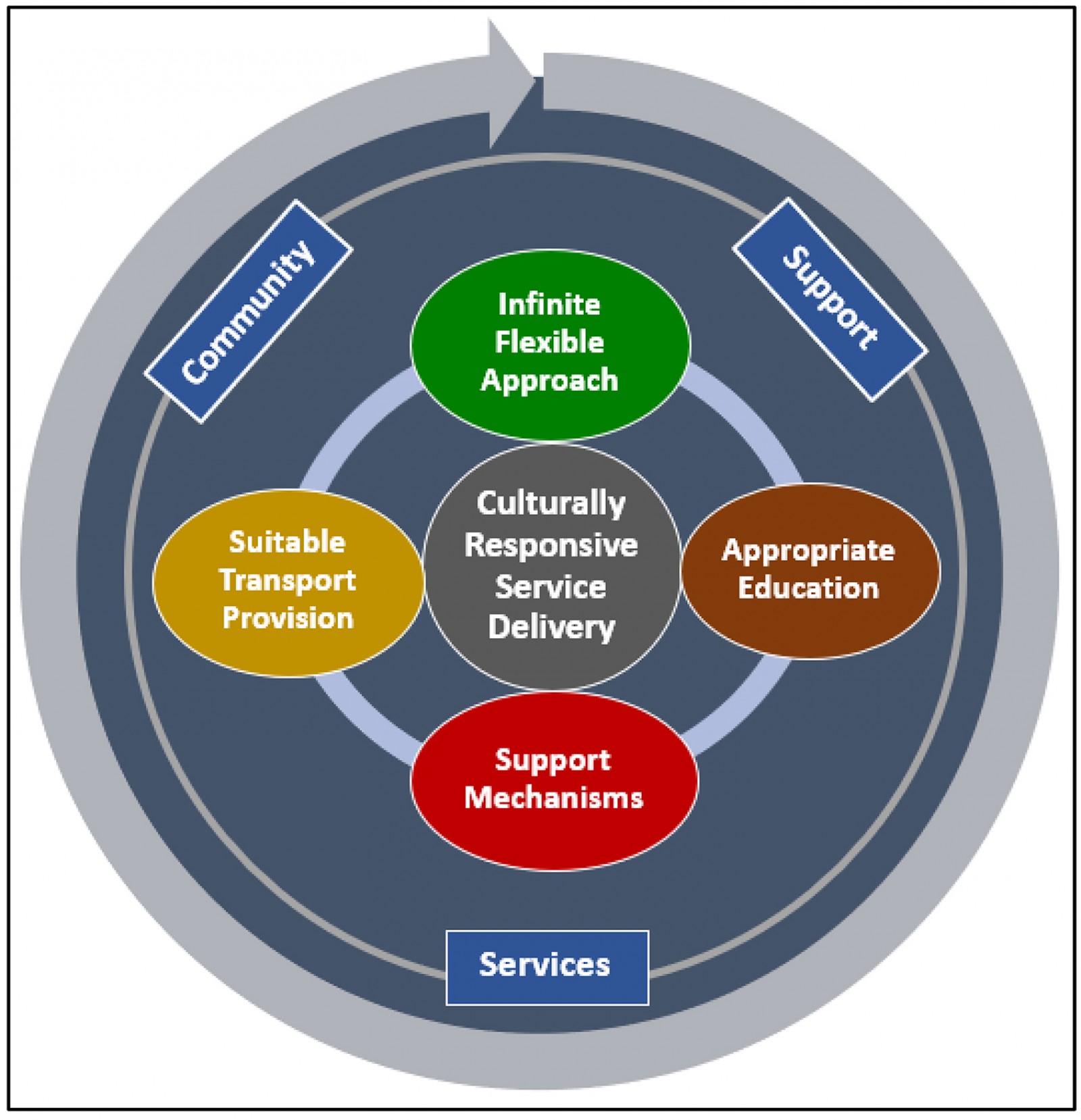

Incorporating SDoH into the clinical management of type 2 diabetes for Indigenous Australians involves a central theme of culturally responsive service delivery. In addition, five individual yet interrelated themes emerged as being essential for SDoH to be identified, navigated and incorporated into the usual clinical care for Indigenous Australians with diabetes. The six themes were:

- culturally responsive service delivery

- an infinite flexible approach to service delivery

- appropriate education for both Indigenous Australians with diabetes and non-Indigenous health professionals

- support mechanisms for Indigenous Australians

- suitable transport provision

- community support services.

Figure 1 provides a diagrammatic representation of these interrelated themes.

Theme 1: Culturally responsive service delivery

Both Indigenous Australians with diabetes and IHWs discussed aspects that suggested a culturally responsive service should be provided when identifying and accommodating the unique needs of Indigenous Australians as part of diabetes care. Participant comments suggested that a culturally responsive service fundamentally requires an all-encompassing, holistic approach.

It’s that whole, holistic, you know, not just their health, it’s everything! (IHW 7)

More specifically, IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes indicated that incorporating SDoH into care for Indigenous Australians in a culturally responsive way encompasses client involvement in their own care, IHW roles in providing care and service delivery approaches for Indigenous Australians with diabetes, generational acknowledgement and inclusion in care, and effective communication. Each aspect is detailed below.

Table 2: Characteristics of Indigenous Australians with type 2 diabetes

Table 3: Characteristics of Indigenous health workers26,27

Figure 1: The six identified themes for the social determinants of health in clinical care for Indigenous Australians with type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1: The six identified themes for the social determinants of health in clinical care for Indigenous Australians with type 2 diabetes.

Client involvement in their own care: Indigenous Australians with diabetes reported their desire to be involved in all of their own healthcare decisions. They felt this would allow them the opportunity to contemplate the appropriateness and achievability of the suggested type 2 diabetes self-management strategies. IHWs reinforced this notion. They discussed the necessity of client involvement to ensure the appropriateness of interventions, and an understanding of self-management activities. Furthermore, the IHWs emphasised the importance of Indigenous Australians with diabetes establishing their own self-management goals.

it’s always best to … run it past with the client … and always get consent from them, because it’s their own right, you know, yeah … And um, listen. Jot things down, let them do the talking ... Ah, you as a health professional, you be just, be taking notes, help them through and then you and the client sit down and work out a strategy (IHW 1)

Have a meeting with the client, with the patient, and see if they got a good understanding with what’s going on … (IHW 2)

IHW roles in providing care: Indigenous Australians with diabetes portrayed IHWs as key to achieving the fundamentals of type 2 diabetes self-management, such as attending medical appointments, understanding medications, navigating health systems and accessing various other community support. They expressed an appreciation for the diverse range of support the IHWs provided.

[IHW] has been a big help to everybody around this area … She’s from [location] and she comes up here, and you know, wants to know if everything is all right – how are youse, and you know, you need anything? (Indigenous person with diabetes (IPWD) 1)

The IHW commentary augmented this and exemplified their supportive attitude regarding client care. They portrayed an unbounded willingness to provide support for the diverse range of issues faced by Indigenous Australians with diabetes.

So we understand. And a lot of people come to us needing help. And it might be something that’s very private and stuff. And they’ll talk to us and we can either guide, support, be there with them … So we walk with them. (IHW 6)

we absolutely back our mob up … because it helps us to help them. You know. The client with their health journey, because, you know, you are doing stuff that, you know, and we link up … So we’re using and working together with community members for somebody’s health journey. (IHW 6)

Service delivery approaches: Health services delivered to Indigenous Australians with diabetes centred on them feeling comfortable, respected and safe. Providing type 2 diabetes care in this manner was appreciated, and the IHWs perceived this as a fundamental part of their role. This approach also appeared to assist with client engagement in health care.

Comfortable, yeah … Go out to their own environment … It’s coming down to respect, you know in making them comfortable, and make sure they’re engaging and all that, you know (IHW 7)

instead of just going to the doctor it’s just a quick visit and, blah blah, and home again. Whether it’s just to sit down, or even watch a thing on the TV screen and whatever (IPWD 2)

Generational acknowledgement and inclusion in care: Including a generational approach to type 2 diabetes care was articulated by both Indigenous Australians with diabetes and IHWs. There was a strong desire to prevent type 2 diabetes spanning generations and negatively affecting the lives of young people. Intergenerational learning and understanding was seen as a possible approach to prevent the consequences of type 2 diabetes experienced by older generations.

I don’t want my grannies [grandchildren] to grow up to be like me, like, either jabbing themselves or taking tablets for the rest of their lives. (IPWD 4)

But what we need to do is just get the younger children, primary school all the way up to high school. Get some elders, and you know, some parents to come and work together. (IHW 6)

Effective communication: Two-way communication between Indigenous Australians with diabetes and non-Indigenous health professionals was most effective when facilitated by an IHW. This assisted the Indigenous Australians with diabetes to better understand health care and enabled IHWs to reiterate and clarify the messages delivered.

yeah and we’re having those conversations on trips to the GPs, or after they’re seen the doctor, even stuff to help them understand in the consult, we just, probably break it down for them on the way home. (IHW 4)

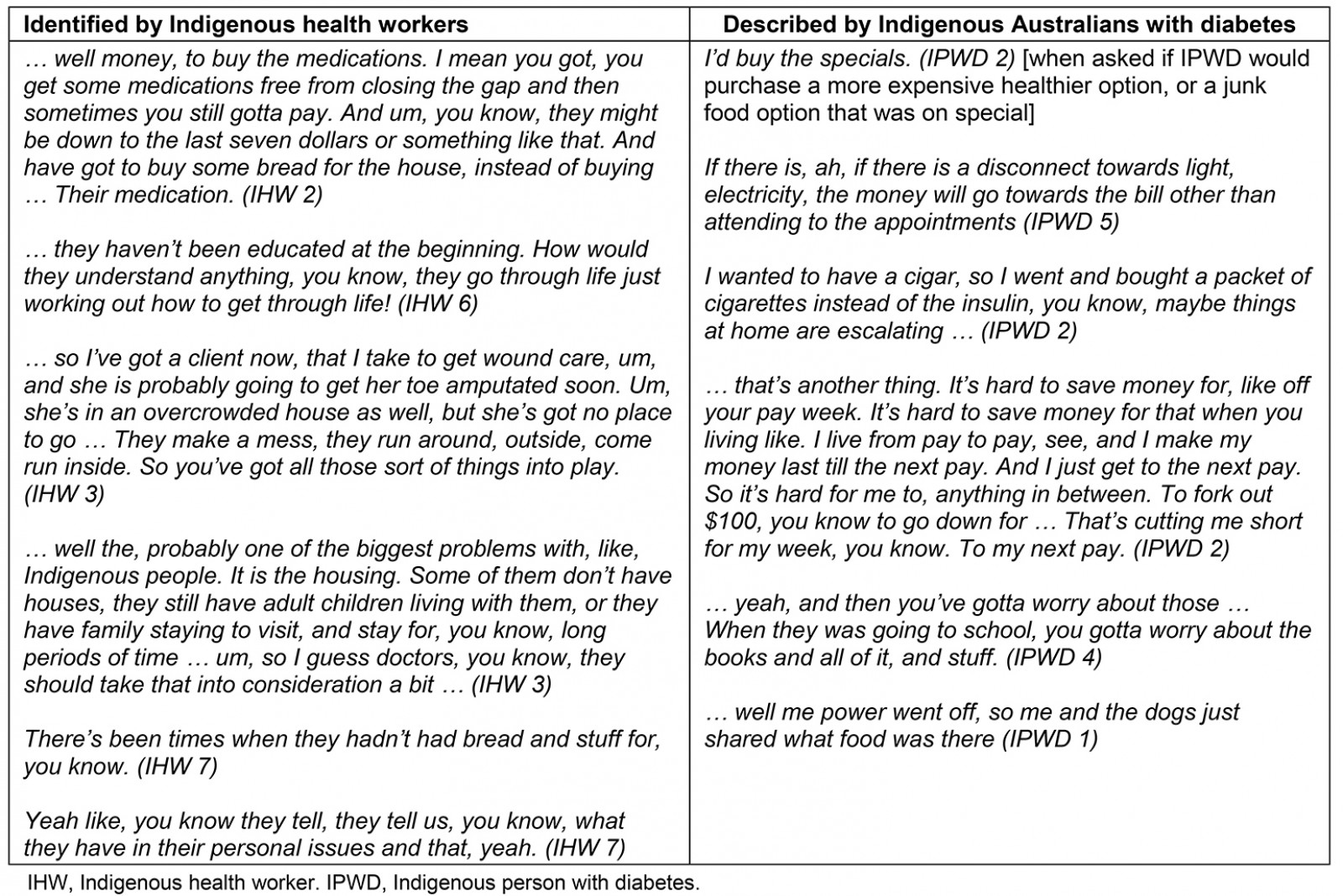

Theme 2: Infinite flexible approach

The lives of Indigenous Australians with diabetes were permeated with competing priorities that hindered effective type 2 diabetes self-management. These were all enmeshed with SDoH and required a multitude of strategies and services to adequately address and navigate them. The IHWs required an infinite flexible approach to be able to walk alongside Indigenous Australians with diabetes to help them navigate these circumstances so that eventually they can prioritise type 2 diabetes self-management.

The extent and diversity of SDoH-related competing priorities as identified by IHWs and described by Indigenous Australians with diabetes are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4: Examples of competing priorities to type 2 diabetes self-management for Indigenous Australians[CG1] [SW2]

Theme 3: Appropriate education

There were two elements to appropriate education. First was the quality, timing and frequency of cultural awareness training for non-Indigenous health professionals. The IHWs felt that cultural awareness training should begin at university level and continue throughout the health professional’s career.

yeah there is always room for improvement

the length of time that runs?

maybe ongoing? (IHW 2, 3, 4)

and that’s probably what needs to be done at the [university] level, before the doctors are even put out from the uni … yeah, at the general medical training (IHW 2 and 3)

The second element related to client education. Understanding type 2 diabetes health messages depended on congruency between learning styles and health professional delivery. This included identifying, acknowledging and allaying fears about type 2 diabetes, and enabling a thorough understanding of type 2 diabetes and its management through the use of visual and practical education strategies.

everything needs to be visual (IHW 2)

You need to try and show them in other ways how to understand. And it has to be visual. (IHW 6)

And we’ve got a few deadly doctors here, um, that will sit down, take the time, go through a care plan, and say ‘do you understand what this is all about? Would you like [IHWs] to explain it a bit better’ … All that sort of stuff … They feel like they’re important. They feel like someone cares ... And that’s where you find them … wanting to go back to that same doctor all the time. (IHW 6)

Underlying the effectiveness of client education was a disparity in health literacy between non-Indigenous health professionals and Indigenous Australians with diabetes.

like myself, I can't read properly. (IPWD 1)

Theme 4: Support mechanisms

Varying types of support mechanisms used by Indigenous Australians with diabetes were identified. This ranged from type 2 diabetes-specific support, such as that provided by the IHWs, to support provided by family members, and indirect support such as workplaces and church groups.

… it’s the support network you gotta have. (IPWD 6)

Our jobs are to support our community members to engage, and ah, with our GP practices and mainstream allied health services so to connect to those services so that they can be supported (IHW 6 (specific support provided by IHWs)[CG3] [SW4] [CG5] )

when they get home, that conversation is going to continue. It’s not just gonna be the patient not knowing how to explain it to any one time. Whether it be their wife, their husband their child that’s looking after them … so that one person in the household has got an understanding of what they’re going through and then the conversation can continue at home. (IHW 2 (family support))

Plus I’m a Christian too … yeah I feel more relaxed and more, more down to earth. You know, to be going to church and friends in the church and family in the church and that, you know. It’s, yeah it’s, you know, it’s a good thing to be, you know, going to church, being a Christian. (IPWD 2 (indirect support))

Theme 5: Suitable transport provision

The ability for Indigenous Australians with diabetes to access the necessary healthcare services for comprehensive type 2 diabetes care relied on access to suitable transport, at an appropriate time. Both IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes lamented the ongoing insufficiency and inadequacy of transport.

There is a big problem with transport … still, there is a big problem (IHW 6)

like I say, transport! … Yeah to get there, and like home … One of the ladies out [remote location] she uses the ambulance to get her to take it to [regional location] and bring her back sort of thing. (IPWD 4)

One IHW spoke of resorting to putting Elders on a Greyhound bus, to attend medical appointments in a regional town 2.5 hours away, because she had no other choice. Her words articulate the disgraceful lack of transport options.

… we’ve got communities that don’t have that, so that’s a very difficult … So what happens is, they either gotta go, they’ve got a go on the Greyhound bus … Now these are elders … It’s just wrong! ...We’ve had to transport people ourselves because their … you know they don’t want to go because they’re scared ... They don’t understand what’s going on. (IHW 6)

Theme 6: Community support services

The ability and approaches used by IHWs to attend to SDoH issues relevant to Indigenous Australians with diabetes depended on the support services available in the community. The extent of support provided relied on collaboration and the working relationships the IHWs had with these services. The IHWs also required a comprehensive understanding of non-Indigenous services to effectively apply them in an Indigenous context to ensure appropriate referrals and support are provided.

If they have community centres, like [rural locations], really good. They support with um, food relief, um, housing, DV [domestic violence] and stuff like that. (IHW 6)

So we link up with the co-op that would be, that is good with working and understanding, you know, using your, um, bush medicines, food and stuff and then I’d interact with that as well. (IHW 6)

Oh … the understanding … understanding of both worlds. (IHW 1)

Discussion

This study aimed to combine the perspectives of IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes to gain insight into the SDoH-related barriers and facilitators to type 2 diabetes management, and how SDoH could be formally incorporated into the usual clinical care of Indigenous Australians with diabetes. Not surprisingly, the findings confirmed that culture should be the foundation of health service delivery for Indigenous Australians with diabetes. The findings also highlighted that the Indigenous view of health innately encompasses SDoH.

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ view of health is holistic and includes culture, spirituality, tradition, social and emotional wellbeing, as well as physical health. Furthermore, this view of health considers the individual and community as unified and inter-reliant. When realised, this concept empowers and enables an individual’s full potential to be reached, and community wellbeing to be achieved2,6,28,29. Therefore, health service delivery for Indigenous Australians should parallel this all-encompassing perspective of health30.

The identified themes for incorporating SDoH into the usual clinical care for Indigenous Australians with diabetes reflect a holistic approach to health care, and corresponded with the Indigenous Allied Health Australia description of cultural responsiveness. This definition states that cultural responsiveness:

holds culture as central to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing; involves ongoing reflective practice and life-long learning; is relationship focussed; is person and community centred; appreciates diversity between groups, families and communities; requires access to knowledge about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, peoples and cultures30.

Culturally responsive service delivery is even more crucial when providing services for Indigenous Australians with diabetes who live in socioeconomic disadvantage (those with poor SDoH)31,32. Poor SDoH can hinder optimal type 2 diabetes management through financial limitations, inadequate housing, insufficient transport, poor access to healthy food, lack of support and an inability to access quality health care29,33. Given the inseparable association between poor SDoH and type 2 diabetes34, the obligation for health professionals to identify and address these issues is apparent17. The findings of this study substantiate this and indicate that subsequent troubleshooting around these issues would indeed assist Indigenous Australians with diabetes in achieving improved type 2 diabetes self-management.

The challenges related to SDoH are exacerbated when Indigenous Australians with diabetes reside in rural and remote locations31,33. This was echoed in the current study and amplifies the need to identify strategies to incorporate SDoH into clinical care. Indigenous health services in rural and remote regions require local contextualisation for optimal service delivery4. In addition, flexibility, client education, health professional training, client support, generational change, transport and community services are intertwined with providing culturally responsive and person-centred care30,35.

IHWs are required to embrace their holistic view of health to accommodate for and support the vast range of competing priorities to self-management that Indigenous Australians with diabetes can have. Poor SDoH and the associated coping strategies (eg smoking and alcohol consumption) can also hinder the lifestyle improvements necessary for optimal type 2 diabetes management and general good health5,10. This perpetuating, negative cycle is widely acknowledged in the literature2,36,37 and requires an understanding that competing priorities can take precedence over type 2 diabetes self-management31. By integrating an infinite flexible approach into usual care, IHWs could then have the capacity to assist Indigenous Australians with diabetes with the diverse and ongoing SDoH issues that can arise, so that type 2 diabetes self-management could eventually become the primary goal.

The effectiveness of non-Indigenous health professionals’ involvement in care for Indigenous Australians with diabetes hinges on cultural respect, awareness, sensitivity, safety and competence (cultural responsiveness)30. Appropriate education for health professionals first requires non-Indigenous health professionals to understand the expansive impact of colonialism and transgenerational trauma on the health and wellbeing of Indigenous Australians6. Second, an unending reflexive empathy for the cultural and health belief differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians is essential29,30.

The voices of the IHWs in the current study resonated the requirement of localised and frequent training around cultural practice. Their consensus lamented a rhetorical nature to current cultural awareness training, that leaves non-Indigenous health professionals ill equipped to truly appreciate the impact of Australian Indigenous culture on health management. Their discontent with current practice coincides with an apparent scarcity of literature supporting the effectiveness of cultural awareness training on health outcomes38, and a lacking consensus on a cultural competence curriculum for health professionals39. However, these assertions are not specific to Australian Indigenous culture, and thus should be extrapolated with contextual prudence.

The importance of cultural responsiveness is acknowledged extensively throughout the literature29,30,38,40. The literature suggests that inept cultural practices by non-Indigenous health professionals can result in miscommunicated health messages, reduced healthcare access, lack of self-management confidence and general distrust of non-Indigenous health workers29. To minimise these avoidable situations, cultural education and training (cultural competency) should be contextually relevant37 and should be ongoing41.

Cultural competency is generally incorporated into undergraduate training of health professionals39; however, the quality, frequency and localised nature of this training are difficult to determine. Consequently, a consistent curriculum for all Australian health professionals may contribute to an enhanced understanding of how providing a culturally responsive service can improve health outcomes for Indigenous Australians.

Effective type 2 diabetes management also requires proficient health literacy. Understanding medications, reading food labels, comprehending written and verbal instructions, navigating healthcare systems and providing informed consent are crucial for type 2 diabetes self-management42. The formidable link between education levels, health literacy and diabetes is well documented42,43. The IHWs in the current study indicated that mainstream education and literacy levels were low among many of the Indigenous Australians with diabetes they work with. This, combined with unacceptably high rates of type 2 diabetes among Indigenous Australians2, reinforces the need for the appropriate education around type 2 diabetes self-management strategies for Indigenous Australians with diabetes.

The distinctive learning styles of Indigenous Australians should also be considered. Visual learning appears to be the most effective learning style among Indigenous populations across the world44. Concurring sentiments from IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes in the current study highlighted the importance of this in type 2 diabetes education. A visual and practical approach to client education facilitates comprehension that accommodates for individual learning styles and culture, despite health literacy levels42,44. An example of a visual and interactive diabetes teaching tool for Indigenous Australians can be found on the Australian Indigenous HealthInfonet website45. In addition to considering learning styles, any education to Indigenous Australians with diabetes should consider and respect local culture and be delivered in a meaningful way so it empowers informed decisions about their own health care46.

Providing care for Indigenous Australians with diabetes involves support derived from family, friends, health professionals or various community-based services. This diverse range of support mechanisms can provide support specific to type 2 diabetes self-management, or psychological, social and emotional wellbeing, and general physical support such as assisting with transport47,48. This was supported by an Australian study by Black et al47, which indicated that people with type 2 diabetes relied heavily on informal supports such as spouses and significant others, neighbours and community organisations. This qualitative study was not specific to rural and remote Indigenous Australians; however, it endorses the importance of support mechanisms to enhance self-management for all people with type 2 diabetes.

The benefits of social support are well known5 and were inferred in the current study. Indigenous Australians with diabetes and IHWs reported a reliance on support mechanisms. Involvement of family members was seen as crucial, and participation in community support groups was also advantageous. This was also a key finding in the Conway et al’s study29, where the value of engaging family groups, local community groups and IHWs to enable comprehensive care for Indigenous Australians was described. Furthermore, lack of these supports was seen as a barrier to type 2 diabetes care and self-management.

The absence of transport can impede social participation and access to health care5,49-51. The experiences of IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes in the current study confirmed that lack of suitable transport provision is a major obstacle to accessing health care, and type 2 diabetes self-management. Inadequate transport options, particularly in rural and remote communities, can force IHWs to use undesirable transport modalities in a desperate effort to support Indigenous Australians with diabetes, such as resorting to public transport for community Elders, as described in the results section.

Inadequate transport has also been described in previous studies as a barrier to self-management, healthcare access and good health48,52. The relevance of transport provision intensifies when Indigenous Australians with diabetes live in rural and remote communities, as access to appropriate transport is more unattainable than in larger centres51 and contributes to higher non-attendance rates and decreased healthcare access50,52.

A well-documented, and obvious, solution to this type 2 diabetes self-management barrier is for health services to provide suitable modes of transport52,53. Of course, there is an increased cost associated with this strategy; however, it is insignificant when compared to the high financial burden of hospitalisation, ambulance utilisation and aeromedical retrieval54, all of which can be a result of poorly managed type 2 diabetes. By investing in resources and services that support Indigenous Australians with diabetes to effectively self-manage their health, such as transport provision, the costs associated with improperly managed health care could be reduced.

Despite transport deficits being a well-known barrier to optimal health, and the strong advocacy for health services to provide transport48,51-53, the current study identified that inadequate transport remains an existing and problematic issue in this region. Services for Indigenous Australians with diabetes could potentially improve healthcare access, and therefore type 2 diabetes outcomes, and reduce healthcare expenditure by merely providing suitable transport as a routine part of health service delivery.

Assisting Indigenous Australians to access and engage with community support services is an integral part of the IHW’s role26. Effectiveness in this role pivots around collaborative relationships and partnerships with available support services55, an in-depth knowledge of service capacity, reach and scope, and facilitating ongoing access and engagement53,55. Without this role, access to vital services could be inhibited because of cultural differences and social barriers11 for Indigenous Australians. Furthermore, the absence of culturally appropriate services within the community restricts service use53.

Davy et al53 provide a broad description of access in their ‘Accessibility framework for Indigenous people accessing Indigenous primary health care services’. This framework has five main components: approachability, acceptability, availability, affordability and ability to engage. It may provide guidance for IHWs to work with community organisations to enhance accessibility and engagement for Indigenous Australians with diabetes. Conceivably, this framework could improve access and engagement of previously ‘inaccessible’ community support services for Indigenous Australians with diabetes. Using the framework may not solve the issue of unavailable services within the community; thus lack of community services requires further research. Nonetheless, improving the accessibility of currently available services is likely to improve care for Indigenous Australians with diabetes.

The six themes identified in the current study may assist health professionals and health services incorporate SDoH into the clinical management of type 2 diabetes for Indigenous Australians. They are interrelated and seen as the ‘whole being a sum of its parts’, which reflects a holistic approach to Indigenous Australian health. Locally contextualising these themes to other communities may contribute to a broader reduction in the disparities between Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous health resulting from poor SDoH.

Limitations

Despite extensive effort to ensure the voices of all participants were correctly portrayed, it was not possible to contact the Indigenous Australians with diabetes for member checking because of the transient nature of their lifestyles. This issue was discussed with ZC and RR, and instead their comments and perspectives were collated and explained in detail to ZC and RR. This was seen as the most appropriate approach to addressing this issue, as ZC and RR have strong and enduring relationships with all the Indigenous Australians with diabetes who participated in the study.

The study was relatively small (N=14) and therefore may not reflect the views of all IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes in North Queensland. However, both IHWs and Indigenous Australians with diabetes provided service to, or lived in, numerous North Queensland communities (n=7). The identified themes were highly consistent across all interviews and yarning circles and may indicate a reasonable level of transferability to other North Queensland communities; however, the validity should be considered if the ‘SDoH approach’ is to be applied elsewhere.

Finally, the findings are not representative of all Indigenous populations across Australia, and only reflect a North Queensland perspective. This is not necessarily a limitation; however, it requires acknowledging. Consequently, the authors recommend caution in directly transferring this SDoH approach to other regions, and strongly recommend local contextualisation first.

Conclusion

Incorporating SDoH into clinical care for Indigenous Australians with diabetes requires a holistic approach that reflects the Indigenous view of health and wellbeing6,29. This study confirmed that cultural responsiveness should be at the centre of care provided to Indigenous Australians with diabetes. Care is then enhanced by applying an infinite flexible approach to type 2 diabetes management. Indigenous Australians with diabetes also require support people and other support mechanisms to walk with them on their type 2 diabetes journey. Appropriate education about type 2 diabetes for Indigenous Australians with diabetes, and ongoing cultural competence training for health professionals, are also essential components. Finally, but equally important, is the provision of transport that suits the specific needs of Indigenous Australians with diabetes, and the availability and accessibility of supporting services within the local community.

Suboptimal type 2 diabetes self-management among Indigenous Australians, because of poor SDoH, may be preventable, and therefore calls for supplementary approaches to diabetes care. Incorporating SDoH as part of the usual clinical care, and assisting Indigenous Australians with diabetes to overcome or enable self-management despite them, could improve health outcomes. Furthermore, incorporating SDoH into the usual clinical care of type 2 diabetes may help to narrow the unacceptable health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians4.

Acknowledgements

Much gratitude is extended to the non-Indigenous, credentialled diabetes educator who assisted in facilitating Indigenous Australians with diabetes recruitment and data collection.

references:

You might also be interested in:

2006 - Medical students' assessments of skill development in rural primary care clinics