Introduction

Malawi is a low-income country with a considerable mismatch between its predominantly young population and the health workforce trained to serve it. Approximately 42% of the population is aged 0–14 years1. Its median paediatrician-to-child population density is only 0.5 per 100,000, and low compared to the African and global median densities of 0.8 and 32, respectively2,3. Most paediatricians work in urban areas, where only 18% of the population lives4. To address the mismatch between urban and rural areas, the Kamuzu University of Health Sciences initiated a specialised training program in 2012, the Bachelor of Science in Paediatrics and Child Health (BSc PCH) for clinical officers, a mid-level medically trained clinician cadre, formerly often referred to as non-physician clinicians5.

The program aims to train a cadre to function optimally as district leaders for paediatrics and child health5. This involves being able to independently manage the most common paediatric conditions at a district hospital level, to mentor and teach other cadres, for example nurses, and also to identify and perform projects to improve the quality of care in that facility. The training spans 3 years and is divided into six semesters. It begins with a semester of basic medical sciences, followed by five semesters of supervised clinical placements. Two semesters are in the (mostly rural) district hospitals, and three are in the central hospitals. The graduates were supposed to receive 1-year post-graduation mentorship from paediatricians based at the central hospitals they refer to, a program component not operational to date.

As of 2022, 29 clinical officers had graduated. The Malawi Medical Council has recognised them as clinical associates since 2022; however, they must apply for vacancies to be promoted to clinical associates, and vacancies at government district hospitals are limited. Nevertheless, the Malawi Ministry of Health and Population aims at training 84 more BSc PCH clinical officers by 2030 and securing scholarships for the first baseline year, according to its current health sector strategic plan6. Currently there is an annual intake of 12 students on average.

Kamuzu University of Health Sciences aimed to train 33 BSc PCH clinical officers by the end of 2020 to staff each district hospital with a graduate, with paediatric specialists from the four central referral hospitals as supervisors5,7. Managed clinical networks were to support this cadre utilizing central hospitals’ resources to enhance child health care at all levels5,8. Kamuzu University of Health Sciences and the Ministry of Health and Population viewed BSc PCH clinical officers as central to the paediatric public healthcare system, particularly for the peripheral, rural settings, and perceived their full integration into the public system and provision of a supportive environment essential for the cadre’s effectiveness and retention. However, to date, little is known about BSC PCH clinical officers’ workplace realities, their workplace satisfaction, and intention to remain in the public system7,9-11.

Job or workplace satisfaction is critical for organisational performance, commitment, team performance, overall staff wellbeing, and turnover12. Staff turnover and internal migration such as moving from public to private sector, from clinical to non-clinical roles, or from rural to urban areas, are closely linked to workplace satisfaction13. It is evident that satisfied staff find it harder to leave, while dissatisfied staff pursue new opportunities12. Therefore, understanding factors influencing workplace satisfaction and retention of health workforce in the public sector is essential to address the human resources crisis, especially in low- and middle-income countries14.

According to Herzberg's two-factor theory, motivational and hygiene factors contribute to job or workplace satisfaction by addressing needs of individuals12,15,16. Motivational factors are work-related and create positive feelings of satisfaction. These factors include advancement opportunities, an appealing nature of work, professional growth prospects, responsibility and authority, recognition, and achievement. In contrast, factors such as interpersonal relations, salary and benefits, organisational policies, supervision, and working conditions that address needs related more to the organisational environment, are so-called hygiene factors12. Addressing hygiene factors in isolation may prevent dissatisfaction; however, without addressing motivational factors too, achieving workplace satisfaction and retention is unlikely, according to Herzberg17. Therefore, two separate incentive mechanisms are suggested to achieve workplace satisfaction: one to provide opportunities for personal and professional growth, recognition, and achievement; and another to prevent dissatisfying factors related to management practices, salary, relationships, and organisational policies15.

Considering the theoretical underpinning discussed above and Malawi’s health system stakeholders’ aspirations, we aimed to investigate the BSc PCH clinical officers’ workplace satisfaction, the influencing factors, and the likelihood of their retention in current positions. Additionally, we assessed their contributions to child health care to provide insights into the training program's effectiveness and guide future investment.

Methods

Study design and sampling frame

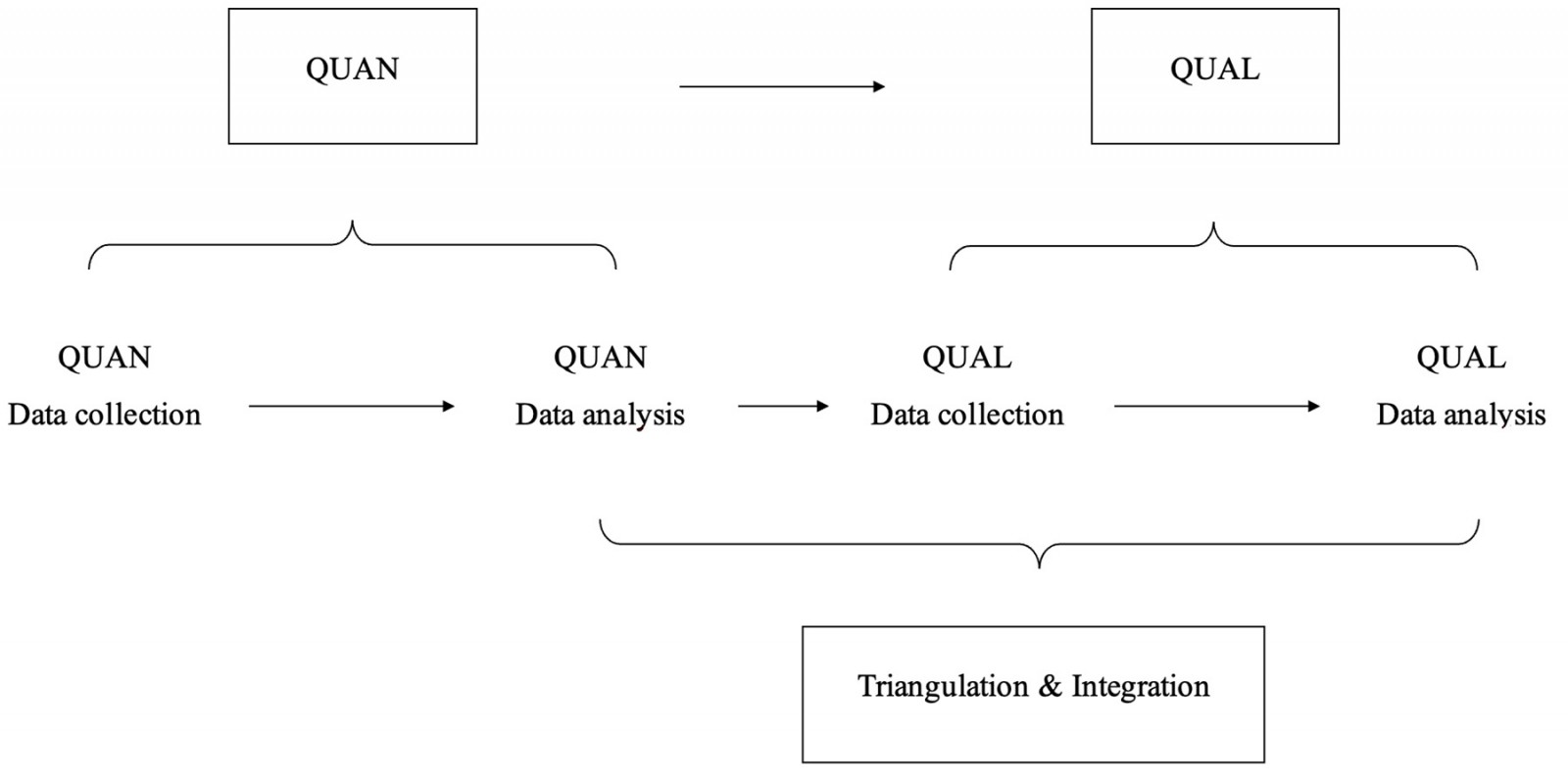

We used a mixed-methods, sequential explanatory design where the qualitative study follows the quantitative study (Fig1)18. A workplace satisfaction survey was used for quantitative data collection, and in-depth and key informant interview guides as qualitative data collection tools. Data collection took place between January and December 2022.

All 29 BSc PCH clinical officers who graduated and started working were included in the quantitative sampling frame. Purposive sampling was used for the qualitative study and covered all Malawian regions (northern, central and southern), locations and characteristics of health facilities (geographical: urban, semi-urban, rural; population: high-density area, low-density area; infrastructure: from more- to less-resourced facility; facility level: central and district; facility type: public, private, research; responsibility type: clinical, administrative, research) to optimise heterogeneity and perspective. We included supervisors, teachers, and decision-makers at hospitals, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and research projects as key informants.

Figure 1: Study design to investigate Malawian Bachelor of Science in Paediatric and Child Health clinical officers’ workplace satisfaction, retention and influencing factors.

Figure 1: Study design to investigate Malawian Bachelor of Science in Paediatric and Child Health clinical officers’ workplace satisfaction, retention and influencing factors.

Data collection and analysis

Quantitative data

The workplace satisfaction survey questionnaire was developed by adapting published surveys (Supplementary text 1)19-23. It included 11 dimensions and used a five-point Likert scale, with 5 indicating ‘extremely happy’ and 1 indicating ‘not happy at all’. The survey was conducted in February 2022 at the health facilities where the clinical officers were posted; 27 of 29 (93%) BSc PCH clinical officers participated in the survey. Regarding the two non-participants, one clinical officer was deceased and one had no interest. We formed three groups: public district hospitals (reference), public central hospitals, and NGOs, to compare clinical officers’ satisfaction level according to their current posting and intention to leave (yes/no). District hospitals acted as a reference group because the BSc PCH training was designed to train the clinical officers as the district leaders for the rural childhood population. Likert scales were presented as means and standard deviations. We compared the groups independently using the t-test according to Norman (2010)24, and presented the mean values of the satisfaction dimensions for each group as a radar chart using R software v4.4.1 (R Project; https://www.r-project.org). The initial quantitative results were used to develop the qualitative interview guide.

Qualitative data

A semi-structured interview guide was used for both in-depth interviews (Supplementary text 2) and key informant interviews (Supplementary text 3). We selected 15 clinical officers for in-depth interviews and 14 key informants for key informant interviews by purposive sampling. Interviews were conducted in June 2022 at various locations, including the district hospitals, health centres, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences at Lilongwe and Blantyre campuses, NGOs, and research projects in Blantyre and Lilongwe, Malawi. The interviews were recorded with participants´ permission and transcribed afterwards. We analysed the data by applying a modified grounded theory and a thematic approach using MAXQDA v24 (MAXQDA; https://www.maxqda.com)25-28.

Data triangulation and integration

We used methodological, data, and investigator triangulation to enhance validity29. Quantitative and qualitative data were integrated at various stages, following a sequential explanatory design27,30. Quantitative data were collected and analysed first, followed by qualitative data for a more comprehensive understanding. The first author initially analysed the data, which was then triangulated by the second author. Data were analysed separately and combined, contextualised through Herzberg's two-factor theory for deeper insights15,17.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for conducting this study was granted by the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee, Blantyre, Malawi (P.10/21/2340) and the Ethics Committee at the Witten/Herdecke University, Germany (Application no. 179/2020). Informed, signed consent was sought from each participant to take part in the study.

Results

Quantitative data

Out of 27 BSc PCH clinical officers, 10 were from the 2013 intake year, six from 2015, four each from 2014 and 2016, and three from 2017. Among the clinical officers, 78% (n=21) were male. According to their current posting, 48% (n=13) worked at public district hospitals, 30% (n=8) at public central hospitals, and 22% (n=6) at various NGOs, research projects, and faith-based organisations. The median (range) length of working at their current facility was 2 (1–4) years. Only 15% (n=4) came from the same community or district where they were working at the time of the study, although the majority (81.5%, n=22) reported living relatively close to their families.

We followed Herzberg's two-factor theory to present the workplace satisfaction survey results shown in Table 1. Among the motivational factors, moral satisfaction scored high with a mean and standard deviation of 3.94±0.50, and career advancement low (2.01±0.99). Regarding career advancement, clinical officers showed their dissatisfaction with the performance-based selection criteria (1.96±1.09); 15 out of 27 reported not to have annual performance evaluation. Among the hygiene factors, workplace/team harmony scored high (3.85±0.69) and salary and benefits low (2.46±0.80).

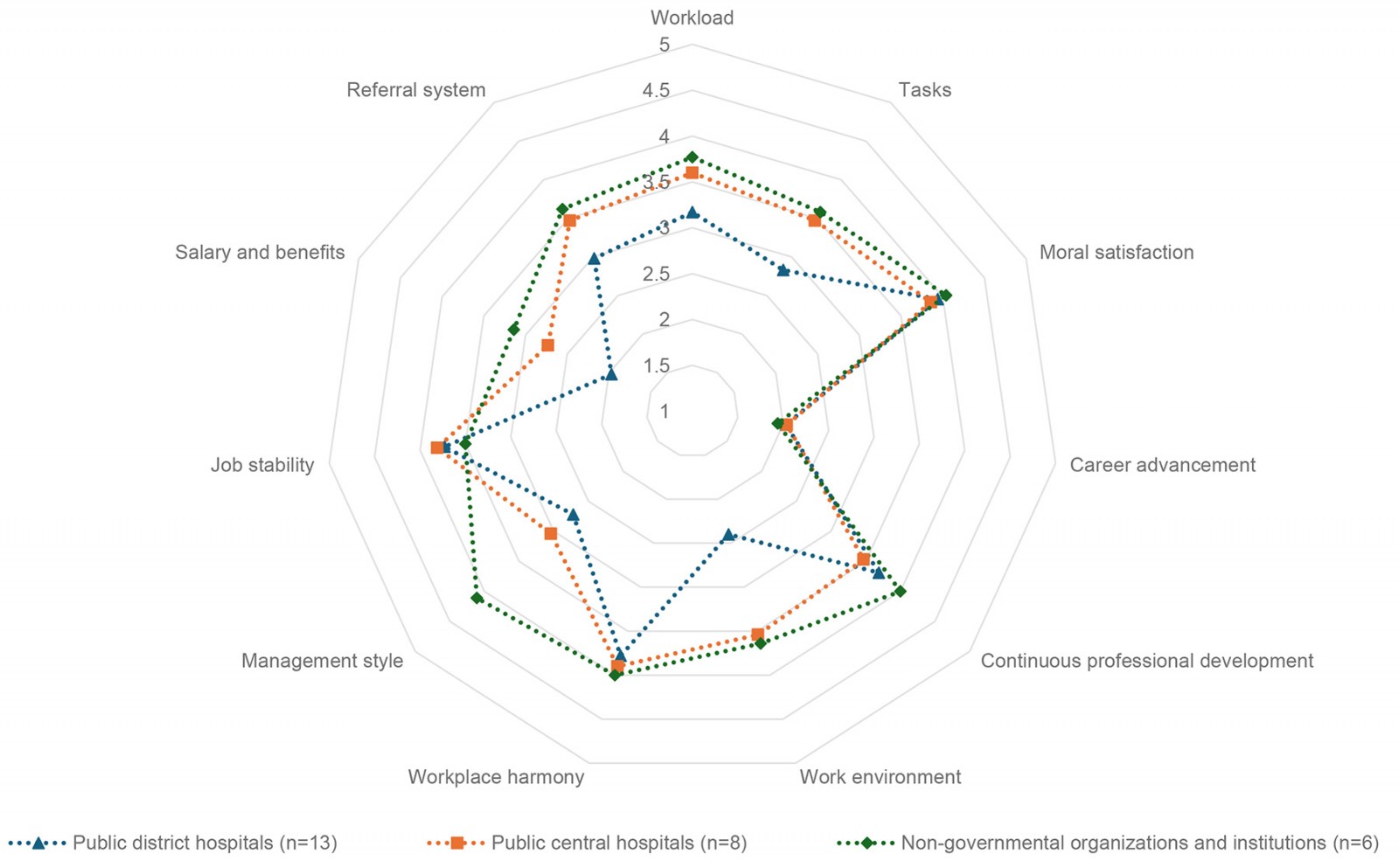

Results of independent t-tests comparing the cadre’s mean workplace satisfaction levels across 11 dimensions according to their current posting are shown in Table 2. Significant differences were found between clinical officers posted at the public district and public central hospitals for the motivational factor dimension ‘tasks’ (eg variety of work and specific job description) (p=0.034), and the hygiene factor dimensions ‘work environment’ (p=0.006) and ‘salary and benefits’ (p=0.032). While differences between the clinical officers posted at the public district and NGOs/institutions for hygiene factor dimensions such as ‘work environment’ (p=0.016), ‘management style’ (p=0.003) and ‘salary and benefits’ (p=0.002) were significant, they were less apparent for motivational factors.

Figure 2 presents the mean scores of workplace satisfaction dimensions according to the clinical officers’ current posting.

Seventeen out of 27 clinical officers considered leaving their current position and wanted to move to NGOs or private hospitals in and/or outside Malawi (but within Africa). We performed an independent t-test to see differences between groups who intended to leave (n=17) or not (n=10). The results (Table 3) showed a significant difference in the salary and benefits dimension (p=0.048).

Table 1: Workplace satisfaction survey covering dimensions of motivational and hygiene factors according to Herzberg15

| Factor and dimension | Items | Result (item mean±SD†) | Average (mean±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivational: Workload | Working hours | 3.59±1.15 | 3.43±0.76 |

| Amount of work and burnout |

3.00±1.11 |

||

| Distribution of workload among team members |

3.56±1.25 |

||

| Work time: clinical versus non-clinical |

3.33±0.92 |

||

| Support received from team |

3.67±1.04 |

||

| Motivational: Tasks | Variety of tasks | 3.48±1.31 | 3.19±0.77 |

| Match between skill and tasks |

3.96±1.13 |

||

| Job description clarity |

2.93±1.27 |

||

| Integration and recognition into health system |

2.37±1.45 |

||

| Motivational: Moral satisfaction | Treatment outcome | 3.37±0.97 | 3.94±0.50 |

| Quality of work (eg effective, efficient) |

4.15±0.60 |

||

| Timeliness at workplace |

4.19±0.74 |

||

| Attendance at work (no absenteeism) |

4.59±0.57 |

||

| Recognition by patients/caregivers |

4.48±0.58 |

||

| Recognition by colleagues/superiors |

4.00±1.00 |

||

| Professional image and respect received for the profession |

3.74±1.06 |

||

| Motivation to continue at the present workplace |

3.00±1.21 |

||

| Motivational: Career advancement | Opportunities to advance career | 2.07±1.41 | 2.01±0.99 |

| Career advancement criteria (eg performance based) |

1.96±1.09 |

||

| Fair performance assessment for career advancement |

2.00±1.21 |

||

| Motivational: Continuous professional development | Availability of trainings | 3.46±1.21 | 3.68±0.82 |

| Match between availability of trainings and actual need |

3.62±0.94 |

||

| Match between gained knowledge and skills and actual need |

3.96±0.92 |

||

| Fair selection process |

3.69±1.23 |

||

| Hygiene: Workplace/team harmony | Understanding among team members | 3.44±0.80 | 3.85±0.69 |

| Effective teamwork |

3.74±1.02 |

||

| Fair treatment by the colleagues |

3.70±0.95 |

||

| Support from supervisor |

4.07±0.92 |

||

| Respectful behaviour of superior/s |

4.22±0.85 |

||

| Free expression of opinion at workplace |

4.00±0.96 |

||

| Hygiene: Work environment | Availability of medical and technical equipment | 2.78±1.12 | 3.01±1.04 |

| Availability of medicines (no substantial stock-outs) |

2.85±1.26 |

||

| Availability of consumables |

2.96±1.53 |

||

| Infrastructure |

3.26±1.20 |

||

| Protection against occupational hazards |

3.19±1.24 |

||

| Availability of stationery |

3.04±1.45 |

||

| Hygiene: Management style | Opportunities to be involved in work-related decision-making | 3.00±1.33 | 3.12±1.15 |

| Information provided about the job life |

3.15±1.35 |

||

| Access to workplace info |

3.22±1.15 |

||

| Hygiene: Job stability | Job stability (certainty or uncertainty) | 3.81±1.11 | 3.70±1.06 |

| Job status (civil/private/contractual) |

3.59±1.22 |

||

| Hygiene: Salary and benefits | Salary amount | 2.07±1.00 | 2.46±0.80 |

| Regularity of salary |

2.81±1.30 |

||

| Match between salary and skills |

2.07±1.00 |

||

| Match between salary and workload |

2.04±1.02 |

||

| Other benefits (eg retirement, bonus, allowances) |

2.26±0.94 |

||

| Leave (eg annual, sick leave) |

3.48±0.98 |

||

| Hygiene: Referral system | Referral system is in place (eg guidelines available) | 3.70±1.32 | 3.27±1.13 |

| Access to all referral health facilities |

3.85±1.29 |

||

| Tracking option with standardised forms and reporting |

2.85±1.32 |

||

| Logistics plan for emergencies (eg transport, funds) |

2.67±1.77 |

† Maximum score is 5. A higher score indicates higher levels of workplace satisfaction.

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2: Comparison of workplace satisfaction dimensions according to Malawian Bachelor of Science in Paediatric and Child Health clinical officers’ current postings

| Factor | Dimensions | Group 1 (n=13) (mean±SD)† | Group 2 (n=8) (mean±SD) | Group 3 (n=6) (mean±SD) | p¶ Group 1 v Group 2 | p¶ Group 1 v Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivational | Workload | 3.17±0.73 | 3.60±0.77 | 3.77±0.71 | 0.225 | 0.121 |

| Tasks |

2.83±0.74 |

3.47±0.54 | 3.58±0.83 | 0.034* | 0.089 | |

| Moral satisfaction |

3.94±0.43 |

3.86±0.56 | 4.04±0.64 | 0.727 | 0.739 | |

| Career advancement |

2.03±0.92 |

2.04±1.12 | 1.94±1.14 | 0.973 | 0.882 | |

| Continuous professional development |

3.69±0.53 |

3.47±1.12 | 4.00±0.98 | 0.610 | 0.537 | |

| Hygiene | Workplace/team harmony | 3.78±0.7 | 3.90±0.44 | 4.00±0.99 | 0.650 | 0.640 |

| Work environment |

2.40±0.99 |

3.54±0.7 | 3.64±0.84 | 0.006* | 0.016* | |

| Management style |

2.72±1.15 |

3.04±1.13 | 4.11±0.58 | 0.536 | 0.003* | |

| Job stability |

3.73±1.22 |

3.81±0.92 | 3.50±1.00 | 0.864 | 0.671 | |

| Salary and benefits |

1.97±0.65 |

2.73±0.73 | 3.14±0.54 | 0.032* | 0.002* | |

| Referral system |

2.98±1.22 |

3.47±0.62 | 3.62±1.45 | 0.241 | 0.370 |

* Statistical significance at p<0.05.

† Maximum score is 5. A higher score indicates higher levels of workplace satisfaction.

¶ Independent t-test.

Group 1, public district hospitals. Group 2, public central hospitals. Group 3, non-governmental organizations and institutions. SD, standard deviation.

Table 3: Comparison of Malawian Bachelor of Science in Paediatric and Child Health clinical officers’ intention to leave according to the workplace satisfaction dimensions20

| Factor | Dimensions | Total (n=27) (mean±SD) | Turnover intention (mean±SD)† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes |

No |

p¶ | |||

| Motivational | Workload | 3.43±0.76 | 3.35±0.74 | 3.56±0.81 | 0.516 |

| Tasks |

3.19±0.77 |

3.31±0.76 | 2.98±0.78 | 0.290 | |

| Moral satisfaction |

3.94±0.50 |

3.90±0.59 | 4.00±0.34 | 0.598 | |

| Career advancement |

2.01±0.99 |

2.10±0.97 | 1.87±1.06 | 0.578 | |

| Continuous professional development |

3.68±0.82 |

3.71±0.83 | 3.64±0.86 | 0.851 | |

| Hygiene | Workplace harmony | 3.85±0.69 | 3.86±0.76 | 3.87±0.58 | 0.988 |

| Work environment |

3.01±1.04 |

2.84±0.97 | 3.30±1.14 | 0.305 | |

| Management style |

3.12±1.15 |

3.16±1.14 | 3.07±1.23 | 0.852 | |

| Job stability |

3.70±1.06 |

3.65±0.98 | 3.80±1.23 | 0.7420 | |

| Salary and benefits |

2.46±0.80 |

2.22±0.72 | 2.87±0.8 | 0.048* | |

| Referral system |

3.27±1.13 |

3.28±1.03 | 3.25±1.33 | 0.953 | |

* Statistically significant at p<0.05.

† Maximum score is 5. A higher score indicates higher levels of workplace satisfaction.

¶ Independent t-test.

SD, standard deviation.

Figure 2: Radar plot comparing mean scores of workplace satisfaction dimensions according to Malawian Bachelor of Science in Paediatric and Child Health clinical officers’ current posting.

Figure 2: Radar plot comparing mean scores of workplace satisfaction dimensions according to Malawian Bachelor of Science in Paediatric and Child Health clinical officers’ current posting.

Qualitative data

Table 4 summarises themes from the workplace satisfaction survey and findings from BSc PCH clinical officers’ and key informants’ interviews, according to Herzberg's two-factor theory12,15.

Table 4: Determinants of workplace satisfaction: display of quantitative and qualitative results according to Herzberg's two-factor theory12,15

| Factor | Dimensions (mean±SD) | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Motivational |

Workload (3.43±0.76) |

They [BSc PCH clinical officers] are forced in the district hospital to do general stuff. So, it demotivates a lot because you feel like you are not being recognized. (in-depth interview 4) There was no continuous supervision … I need an external check to make sure that the things I am doing are right … Because I can continue doing the same things without knowing that maybe I am doing wrong. (in-depth interview 2) |

|

Tasks (3.19±0.77) |

If you go to Medical Counsel now, we do not even have a job description for this Cadre. So, it is just a general job description for a clinical officer, it is not specific to paediatric … they are forced in the district hospital to do general stuff until now. So, it demotivates you a lot because you feel like you are not being recognized … (in-depth interview 4) The government is not recognizing us. The ‘Clinical Associate’ title is known to the Medical Council, but it is not known to the government. The government up to now has not recognized the post. (in-depth interview 5) It [BSc PCH training] helps to transfer some skills to our juniors [nursing, medical student] … the interesting part of it is when you are conducting supervision and mentorship in a way you are teaching yourself. (in-depth interview 3) |

|

|

Moral satisfaction (3.94±0.50) |

Motivation that I have is about the mortality that has gone down now. Because at first, we are having a lot of patients who were dying in the hospital. Because we are not able to manage some conditions. But now after coming from college [after completing BSc PCH] and seeing our mortality rate is now going down … I think I have contributed something to this to the care of the children. (in-depth interview 12) I have increased my competency in delivering the care … the best care for paediatric population. (in-depth interview 13) … the vast knowledge I have acquired [after completing BSc PCH training], I am able to apply it in terms of counselling the guardians, the patients, and even other clinicians … literacy levels are not high in our setup, so it requires skills to explain so that they [patients’ family] understand … when they understand what you are explaining, it gives them comfort. And at the same time, there are stress-free, and also they adhere to the information you give to them … (in-depth interview 10) I have seen a lot of appreciation from the guardians of the patients, even the fellow workers … they [fellow worker] depend on you or they rely on your skills and the knowledge. (in-depth interview 7) |

|

|

Career advancement (2.01±0.99) |

… they [BSc PCH clinical officers] are actually driving to just a blind sack [dead end] … the endpoint is just the BSc so far, unless someone goes to do public health … Someone does paediatric and child health and then does public health. Yes, there is a relationship but … this is not typical in the ward [clinical]. (in-depth interview 9) |

|

|

Continuous professional development (3.68±0.82) |

The clinical officer cadre has actually been formed as a cadre which would actually be there working in the ward … but they are not given opportunities to upgrade themselves. (in-depth interview 9) Maybe if there is a training you want to attend to improve your knowledge that was not being accepted [by the authority]. Because they want you to be always available at the hospital. (in-depth interview 2) |

|

| Hygiene |

Workplace/team harmony (3.85±0.69) |

There is good teamwork that also motivates me in terms of patient management and providing quality care. (in-depth interview 7) … in a hospital setting, we work as a team. So, there is a good teamwork among us, the health care workers. And also there is mutual respect. So, people are able to recognize me as one of the persons who can offer the best for paediatric patients. (in-depth interview 13) … you are a clinical something, what they [other team member] call me … They [other team member] did not accept who I am now. (in-depth interview 8) |

|

Work environment (3.01±1.04) |

Most of the district hospitals do not really have the guidelines at their fingertips. (key informant 9) Our facility has no space for admission. (in-depth interview 3) We don't have proper tools, equipment, and supplies. We needed to have a nursery and paediatric ward. (in-depth interview 8) |

|

|

Management style (3.12±1.15) |

I have been serving in various levels in management … the skills that we got [from BSc PCH training] are also helping me to manage the offices quite well. (in-depth interview 3) … having a BSc you are given a higher grade than the previous one and that grade will automatically give you some additional roles and responsibilities … I am given a position of chief clinical officer … like a supervisor of other clinical officers … it motivates and you become confident. (in-depth interview 1) |

|

|

Salary and benefits (2.46±0.80) |

The only demotivating factor is that we are not promoted since we finished our schools. (in-depth interview 14) The government has promoted me … that’s been a great motivating factor for me. (in-depth interview 11) |

|

|

Referral system (3.27±1.13) |

… the communication between the district hospital and the central hospitals at least now is better compared to the previous time … now we are acting as a focal person in the departments in the districts. (in-depth interview 14) [District level] Lack of getting feedback from the referring centre, from the tertiary centre. Because whenever you manage a patient now, you would always want to get feedback from the other end like what the patient's outcome, what was the diagnosis, what did they do in terms of the treatment, and anything else that we would have done from this side that would have improved the patients' outcome. (in-depth interview 13) [Central/tertiary level] … some of the referrals are incomplete. It is very difficult for us to know what type of drugs they received, and for how long. Because usually the referral letters, they just write the name of the drugs, not the duration. (in-depth interview 12) |

BSc PCH, Bachelor of Science in Paediatric Child Health. SD, standard deviation.

Suggestions for improvement from the participants

The clinical officers and key informants suggested several measures to sustain satisfaction and retain clinical officers in the public system. They emphasised the need for a clear job description, and recognition and promotion opportunities. Participants urged collaboration between the Ministry of Health and Population, Malawi Medical Council, and Kamuzu University of Health Sciences to implement policies preventing internal migration.

The job description that the Ministry of Health or the local council need to revise … Because job description is an important thing. (in-depth interview 7)

They [BSc PCH clinical officers] need to be promoted and give them the benefits they are supposed to get to stay motivated … if you promote them, they will fully work as the way they were trained. If you do not promote them, they may seem to you like they are working, but they are not … These organizations [Ministry of Health and Population, Malawi Medical Council, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences] should work together to use them fully. (in-depth interview 8)

The Ministry of Health should move fast. Because now we are losing … some of my colleagues have left already. Because they were not motivated. They were not recognized. (in-depth interview 4)

Recognizing the importance of supervision and mentorship, continuous professional development (CPD), and career advancement options as crucial for workplace satisfaction, the participants also offered several suggestions.

… need more support from the central level, mentorship programs from the tertiary level and also learning visits, attachments to make sure you improve your knowledge and skills. (in-depth interview 4)

Previously, there was the program which was organized by PACHA [Malawian Paediatrics and Child Health Association] … collecting all clinical officers of Malawi in one place for a conference. They could present and share ideas about problems they are facing. But we just noticed that has stopped. If that can be revived, that can really be helpful. (in-depth interview 8)

They [Kamuzu University of Health Sciences] should look at … what is their [clinical officers’] future in the clinical settings. (in-depth interview 6)

… we might have the knowledge of paediatric care as a whole but as an individual sometimes you are interested in a certain specialty. Because in paediatrics, you can have paediatric oncology, cardiology, palliative care, paediatric gastroenterology. So, you feel maybe as BSc you can still be mentored in those depending on whatever you are interested in. (in-depth interview 15)

The supervisors, as key informants, acknowledged their responsibility towards the graduates and provided suggestions to improve their support and guidance.

As supervisors we need to make sure that we are giving them more tasks and responsibilities, recognizing them at the lower level, engaging them in more supervisory roles as well as also managing the departments for themselves. (key informant interview 7)

Acknowledging the importance of this specialised cadre, participants suggested continuing the program with increased intake, offering more scholarships, maintaining the program's quality, and opening more positions for the clinical officers.

We need more specialized and more trained individuals … now we need to train more. So they can be at a district hospital, can be at a central hospital, and can be even at primary facilities. (key informant interview 9)

My recommendation is to the government to employ more clinicians [BSc PCH clinical officers]. (in-depth interview 13)

Discussion

Our study offers valuable insights into the workplace satisfaction of specialised paediatric clinical officers in Malawi. Applying Herzberg's two-factor theory, we identified motivating and hygiene factors determining their workplace satisfaction. Graduates reported high satisfaction related to motivational factors, such as improved morale due to enhanced knowledge and skills contributing to better patient care and disease outcomes. However, they expressed dissatisfaction with their professional recognition process, the absence of a specific workplace description, and limited career opportunities, including a lack of clinical career pathway and CPD. A supervision and mentorship program was also lacking. Regarding hygiene factors, teamwork contributed to workplace/team harmony, but other factors, such as adequate salary and benefits, well-developed infrastructure, and medical supplies and clinical guidelines, were lacking. Over half of the respondents considered leaving their current workplaces due to salary concerns. Our results also reveal participants’ suggestions for opportunities to foster positive feelings through motivational factors and to address hygiene factors to prevent dissatisfaction, echoing findings from other studies12,17. These suggestions align with the WHO strategies for developing and retaining healthcare workers at the rural level, including targeted education, rural recruitment, conditional scholarships, financial incentives, and professional support like CPD31. Implementing these strategies may improve workplace satisfaction among Malawian paediatric clinical officers and help retain them in the public healthcare system. Overall, our findings may inform child health human resources practices in Malawi and may be relevant for other countries in the region.

A workforce dissatisfied due to delayed or lack of recognition and promotion may migrate in-country, contributing to internal brain drain. Several respondents were disappointed for not being promoted with increased salary on time and considered leaving the public sector. The Malawi health sector strategic plan (HSSP III) for 2023–2030 confirms our findings6. For example, according to our study data, 29 BSc PCH clinical officers completed their training by 2022, but the report recognised only seven (being promoted as a clinical associate with increased salary scale) in the public sector health workforce by 2022. The graduates either stayed as general clinical officers or have moved from the (rural) district to (urban) central hospitals and from low-wage public sector to high-wage private sector positions (NGOs and donor-funded research projects), dynamics described in other studies as well32-34. Such a situation jeopardises the BSc PCH program’s vision that graduates work as district clinical leaders in more remote, rural settings. Consequently, maldistribution and unavailability of trained personnel at the district level may compromise accessibility, availability, and quality of child health care13.

Fostering a supportive environment that emphasises recognition and promotion appears to be critical to address the barriers to workplace satisfaction, as we observed. Recognition instils a sense of belonging and personal achievement, which in turn encourages retention, as has been shown in previous studies from Malawi, Tanzania, and Afghanistan13,35. Graduates (mainly clinical officers not promoted to clinical associates) consider leaving their current positions, primarily due to their low salaries. They consider moving to private sector NGOs and private hospitals offering higher wages. A comprehensive review of the in-country salary structures, including the private sector (NGOs and donor-funded projects), may help to prevent the public sector BSc PCH clinical officers becoming demoralised and moving away from the public system, especially at the district level. The private sector should be required to adhere to the in-country salary structure and contribute to human resources development rather than merely utilizing the already trained human resources from the public sector, as has been discussed by others36.

Dissatisfaction is reported as higher among graduates posted at the mostly rural district level compared to those in central hospitals, NGOs, and donor-funded research projects. A lack of specific job descriptions forces clinical officers to manage both paediatric and adult patients, increasing their workload. Additionally, the absence of mentorship and regular supervision in the periphery leaves them working in isolation. The dissatisfaction is also reported as higher among the central hospital graduates than those at the NGOs. Underdeveloped facility infrastructure, along with frequent shortages of medical supplies and medicines, prevents graduates working in public health facilities from performing optimally in their clinical roles, leading to dissatisfaction and reduced motivation. Other studies have confirmed that inadequacy in medical supplies and equipment, coupled with high workload and lack of supervision, results in low motivation and performance, ultimately compromising quality of care37-39. Despite the financial and human resources constraints, it is necessary to establish a supportive supervision system and ensure the availability of medical supplies and a clear job description specific for clinical officers/clinical associates to optimise their performance.

Most graduates, irrespective of their placement, reported a lack of career advancement opportunities in the clinical setting or the field of work they are primarily trained for. Many noted the absence of a bridging program that would allow them to enter the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS), reducing the usual 5-year duration. Furthermore, graduates, especially those posted at the district health facilities, frequently reported dissatisfaction due to either absence of CPD opportunities or the unfair selection process. Other studies reported that not having a career pathway, and lack of further training opportunities, act as pull factors and negatively impact on workplace retention32,35,37. Conversely, evidence suggests that offering additional training opportunities and eliminating barriers to enhance professional and personal skills are associated with longer retention in rural areas40. Given that this specialised cadre is trained up to the BSc level and is crucial for the district, they should still be offered career opportunities for paediatric specialties as suggested. Additionally, they could be designated with rewarding responsibilities such as leading districts, teaching and supervising fellow staff, and conducting research. These non-financial rewards may play a vital role in sustaining motivation and securing long-term retention within the public healthcare system.

Despite facing several disappointments, BSc PCH clinical officers in this study reported experiencing moral satisfaction with greater responsibilities after graduation and being able to contribute to quality care, and thereby achieve positive treatment outcomes. They stated that they increased their knowledge and competency in delivering paediatric care, acted as a focal person for referral, and developed their communication skill (eg with patients' families, team members, and referral hospitals). The improved clinical and non-clinical skills made them confident in their daily clinical work. Other studies showed that increased competence and confidence is linked to a sense of autonomy, feeling worthy at the workplace, and developing responsibility to contribute to quality care10,13,41. In our study, graduates also reported receiving appreciation from patients' families and team members, which served as a significant motivational factor. The appreciation received from the team members and supervisors, and the gratitude received from the family members, affect healthcare professionals both professionally and personally. Professionally, they feel motivated to continue working with more dedication. Personally, it generates feelings of wellbeing and satisfaction, and increases self-esteem and motivation42. In contrast, some studies found that a lack of personal and professional support, and appreciation, may demotivate the professionals in the long run, which may compromise patient care and disease outcomes32,33. Therefore, providing essential personal and professional support, including appreciation and gratitude, is crucial for maintaining this cadre's morale and dedication to ensure better child health care in Malawi.

Strengths and limitations

Including in the study 93% (27 of 29) of the BSc PCH clinical officers ever graduated is a strength. Methodological, data and investigator triangulation enhanced validity. The study captures diverse perspectives by gathering input from graduates working in various settings, including public central and district hospitals, NGOs, and donor-funded projects, to identify factors influencing their experiences in different environments. Including various stakeholders as key informants from the public and NGO sector, and in different roles like supervisors, administrators, trainers, and decision-makers, provides a wide-ranging perspective on workplace satisfaction and retention factors.

This study has several limitations. The results may have limited generalisability to other countries and healthcare settings since the study was based solely in Malawi. Nonetheless, the factors influencing workplace satisfaction and retention for this mid-level clinician cadre in the public sector might be applicable to other low- and middle-income countries, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, due to similar healthcare challenges. The self-reported nature of data may introduce bias, for example attribution bias, where participants potentially overestimate or underestimate their circumstances and influential factors, such as recognition and promotion issues in our study. Despite this, the factors identified are consistent with other studies, suggesting minimal bias. Lastly, the absence of a comparison before and after the BSc PCH specialty training limits the ability to assess expectations versus realities. Future studies may build on our findings and re-examine after a certain period to capture changes, and compare factors and experiences.

Conclusion

The BSc PCH clinical officers cadre is designed to ensure quality child healthcare coverage at the district level of Malawi's public healthcare system, with more than 80% of Malawi’s population living in these predominantly rural areas. Our analysis reveals several factors affecting their workplace satisfaction and influencing their decision to remain in or leave the public system. Recognizing the cadre’s importance, the Ministry of Health and Population should develop a policy to enhance BSc PCH clinical officers’ workplace satisfaction. This can be achieved through collaboration with the Malawi Medical Council and Kamuzu University of Health Sciences to address key areas such as a specific job description, opportunities for promotion and salary advancement, supervision and mentorship programs, and strategic deployment of these graduates as already planned. Moreover, the Ministry of Health and Population should engage with all health sector stakeholders, including NGOs and donors, to ensure the policy’s successful implementation.

Specific recommendations include:

- Progress recognition and promotion process: The Ministry of Health and Population should work with the Malawi Medical Council to recognise the clinical officers as clinical associates upon graduation, accelerating the promotion process.

- Supervision and mentorship support: Central hospitals must re-establish supervision and mentorship support for graduates at district level by deploying their specialised paediatricians on a regular basis. This guidance is essential for maintaining efficacy and morale among graduates. Implementing the managed clinical network model could provide an additional advantage, and foster a sense of community and continuous professional support.

- Medical supplies, medicines, and standard operational procedures: The Ministry of Health and Population should strive to ensure the availability of essential supplies and physical availability of standard operational procedures at all levels to standardise service delivery.

- Programs for experience sharing and CPD: The Malawian Paediatrics and Child Health Association should pursue funding to resume programs that facilitate experience sharing among graduates. Kamuzu University of Health Sciences may consider offering further training in paediatric specialties such as oncology, cardiology, palliative care, and gastroenterology as part of the CPD. The training would address the lack of development opportunities in clinical settings and could be aligned with graduates' interests.

By incorporating these recommendations, a Ministry of Health and Population policy may enhance workplace satisfaction, organisational commitment, and the retention of this specialised, mid-level medically trained clinician cadre in the public system, fostering a motivated paediatric workforce and improving child health outcomes in all parts of Malawi, including its rural population.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all participating clinical officers and key informants who volunteered their time and provided valuable information by answering the various questionnaires.

Funding

This study obtained funding for data collection, entry, and transcription from the Internal Research Funds of the Witten/Herdecke University, Germany.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests (financial or non-financial).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the study are not publicly available, to protect participant privacy. However, data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.