full article:

Introduction

The allied health workforce is large and growing in many countries. In Australia, this consists of around 195 000 allied health professionals, up to 25% of the registered health workforce1,2. However allied health services remain poorly accessible in Australia’s rural and remote areas3. In 2016, 17% psychologists, 19% physiotherapists, 21% of optometrists, 23% pharmacists, and 25% podiatrists worked in rural locations, where 29% of the Australia population lives3,4. This article presents a contemporary review of the latest evidence about rural allied health services to inform policy, service development and research for addressing better access in the Australian context.

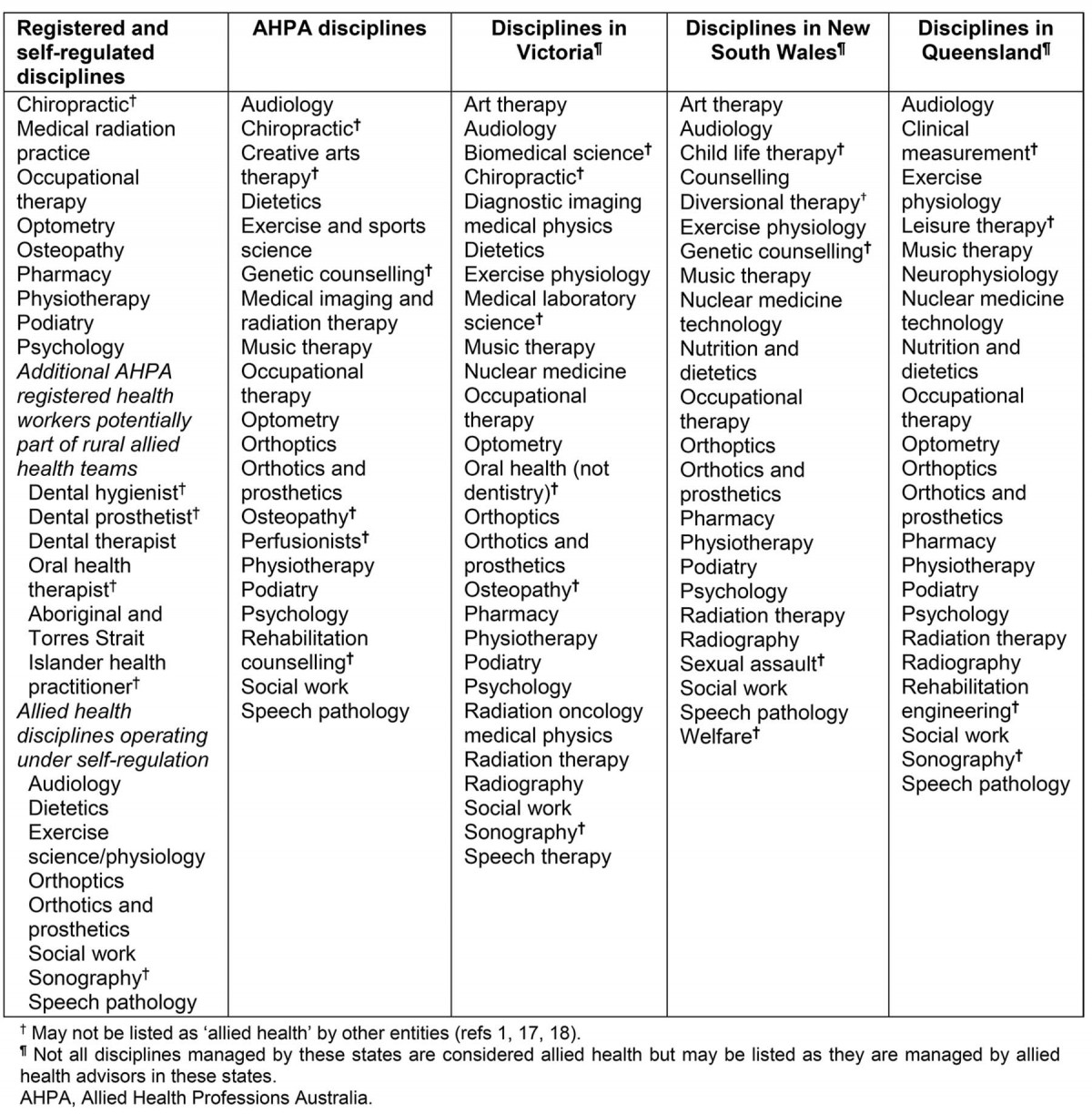

With respect to workforce planning, the term ‘allied health’ in Australia covers a wide range of health professional groups around the world, typically excluding medicine, nursing, midwifery, dentistry and emergency services (Table 1). Professionals are trained in universities2,5, some through Australia’s National Registration and Accreditation Scheme and several others through professional self-regulation1.

The need for allied health services in rural and remote Australian communities is extensive based on complexity of needs within rural populations, in the areas of chronic disease, eye and ear health, maternal and child health, mental health, Indigenous health and access to medicines. A Delphi study identified allied health, mental health, oral health and rehabilitation as core primary care services needed in communities as small as less than 1000 people6,7. Hospitalisation and retrievals data reflect the urgent need to strengthen primary care. Hospitalisations for oral and dental conditions in 2011–2013 were significantly higher for Indigenous infants and primary school aged children from remote areas than age-matched metropolitan controls8. Over 1 year, remote clinic transfers numbered 789 children (aged <16 years; average age 4.4 years) and frequent aeromedical retrievals occurred for people with identified complex chronic diseases who could have been managed locally with multi-disciplinary shared clinical care9,10.

Accessing early intervention and ongoing support is a challenge. Leach et al described otitis media commencing in Aboriginal infants within 3 months of birth, progressing to chronic suppurative otitis media in 60% of cases and not resolving throughout early childhood11. Lack of providers was considered by 85% of parents in rural New South Wales (NSW) as a key reason limiting access to paediatric speech pathology services12. Also described were long travel distances to access services, expensive travel costs, lack of public transport, poor awareness of speech pathology services and delays in treatment due to waiting lists13. Access to rehabilitation in rural and underserved areas is plagued by difficulties with funding, recruiting and retaining appropriately skilled staff14,15.

Allied health policy and service transformation is rapidly developing in Australia. Both national and state/territory governments are engaged in policies – the former largely governing community (private) and the latter governing salaried roles2,5,16-18. In February 2018, the Australian Health Minister’s Advisory Council (AHMAC) formally recognised the Australian Allied Health Leadership Forum as the appropriate forum for the AHMAC and the Health Service Principle Committee to seek allied health workforce advice. Expert advice is also provided by Allied Health Professions Australia.

Rural-specific allied health policy and advocacy started over 20 years ago, via a grassroots organisation called Services for Rural and Remote Allied Health. At a similar time, in 1997 and 2001, the Australian Government started funding University Departments of Rural Health (UDRH) and the Australian Rural Health Education Network respectively19,20. These groups are intended to coordinate multidisciplinary rural training opportunities, including in allied health.

Despite the policy momentum, there has been limited consolidation of the evidence for informing the key priorities for the future of rural allied health policy and research. Although this is a challenging task given the multiplicity of professions, technical expertise, training pathways, sectors and professional governance frameworks, coordinated action is critical5. In 2018/19, Australia’s National Rural Health Commissioner was asked by the National Rural Health Minister to consult with the sector and draw on the available literature to provide advice regarding the current priorities for improving the access, distribution and quality of rural and remote allied health services across Australia21. The aggregation of this literature was considered to have broad applicability for diverse stakeholders and countries and hence considered important to publish.

Methods

A scoping review was selected to allow a number of study designs to be included, and as the method of choice for establishing the extent, range and nature of material and outcomes for informing broad fields such as policy22. As opposed to systematic reviews, which are best suited for narrow research questions and particular types of evidence such as randomised controlled trials, scoping reviews are better suited for exploring broad topics and can include a range of study types. The five-stage framework by Arskey and O’Malley was applied22.

Stage 1 – Identifying the research question

A broad question and key terms were defined to enable breadth of coverage of available local research. The research question was deliberated by a multidisciplinary research and policy team at regular meetings. It was ‘What is known from the existing literature about the training and provision of allied health services to address rural and remote community needs?’ A secondary issue was ‘What is allied health?’

The disciplines included were informed by Table 1, excluding medicine, nursing, midwifery, dentistry and paramedicine, along with non-clinical roles such as biomedicine. Specifically to inform cost-effective and sustainable allied health service models suitable for geographically distributed populations, allied health assistants and oral therapists/hygienists along with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioners were included. Although allied health practitioners work across many sectors, such as health, justice, schools, aged care and disability, the main focus of this work was on the health sector.

Table 1: Different groupings of disciplines registered, included or managed by Australian jurisdictions under the term ‘allied health’

Stage 2 – Identifying relevant studies

To be as comprehensive as possible in identifying primary studies, a selection of search terms was mapped, based on the review questions, and iteratively developed to maximise generalisability while balancing sensitivity to the range of disciplines and rural context of interest. Concepts covered were (Rural OR remote) AND ('health work*' OR 'rural generalist' OR 'allied health' OR 'community health worker' OR 'health assistant' OR 'therap*') AND (train* OR curricul* OR develop* OR course OR placement OR immersion OR skill OR education OR qualification OR competen* OR recruit* OR retention OR *care OR *access OR model OR telehealth OR outreach) AND (Australia OR New Zealand OR Japan OR Canada OR United States OR North America). A Boolean search was also done, based on the terms in each concept.

The search was restricted to high income countries where previous global scale literature reviews had identified the most evidence about primary care/allied health: Australia, Canada, Japan, USA and New Zealand23,24.

Six databases, judged to be of the scope and relevance for the question, were used: Medline, Social Science Citation Index, CINAHL, ERIC, Rural and Remote Health, Informit Health Collection, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Articles were published between February 1999 and February 2019.

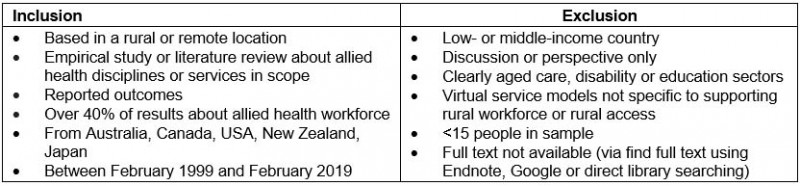

Other published material was identified by key informants as part of the Commissioner’s concurrent national consultation process. The literature was entered into Endnote, duplicates removed, and articles sorted using inclusion and exclusion criteria, which had been iteratively developed through discussion between the authors (Table 2). No other quality criteria were applied to exclude articles because the literature was hypothesised to be emergent and the aim was to define the extent, range and nature of material.

Table 2: Inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the scoping review

Stage 3 – Selecting the studies

Study selection involved reviewing article titles and abstracts for inclusion. This involved weekly discussions with a reference team of mixed policy, research and clinical experience about the range of material in order to develop inclusion criteria. The authors then conducted full-text screening. Extraction criteria were developed based on the research question, pilot tested and refined until considered fit for purpose. Extracted material included country and location, year, health worker(s), study sample, practice context (hospital, community or both AND regional, rural or remote of both), research question (topic), area of clinical care, methods, outcome and enablers or barriers.

Stage 4 – Charting the data

Charting the key themes involved synthesising and interpreting the material by sifting, charting and sorting material according to key issues and themes. The extracted material was initially charted by recording preliminary ideas and thoughts, and discussing these between authors. After initial analysis, articles were re-read and progressively organised into consistent themes using inductive analysis, whereby the material was considered without using a pre-existing coding framework, within an Excel spreadsheet25,26. Articles covering a number of themes were categorised according to the main theme covered, but findings for all themes were presented in all relevant sections of the results and discussion.

Stage 5 – Collating, summarising and reporting the results

The results were organised into a thematic narrative that made sense for informing policy and research priorities. Although not the main focus of scoping reviews, the findings about quality of evidence (key study design and sample issues) were briefly appraised as this was considered important for informing research directions.

Ethics approval

This study used published data and so did not require ethics review.

Results

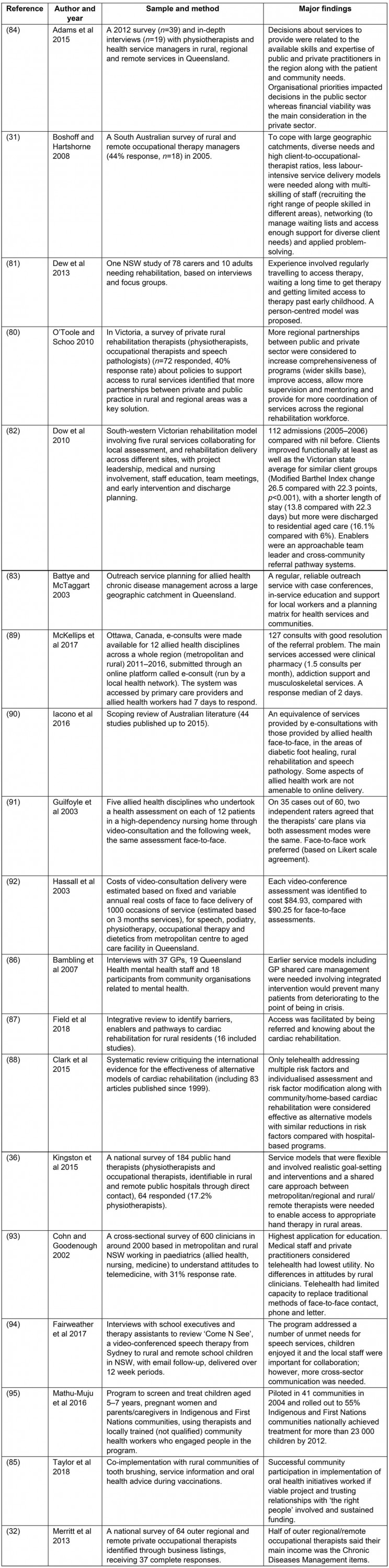

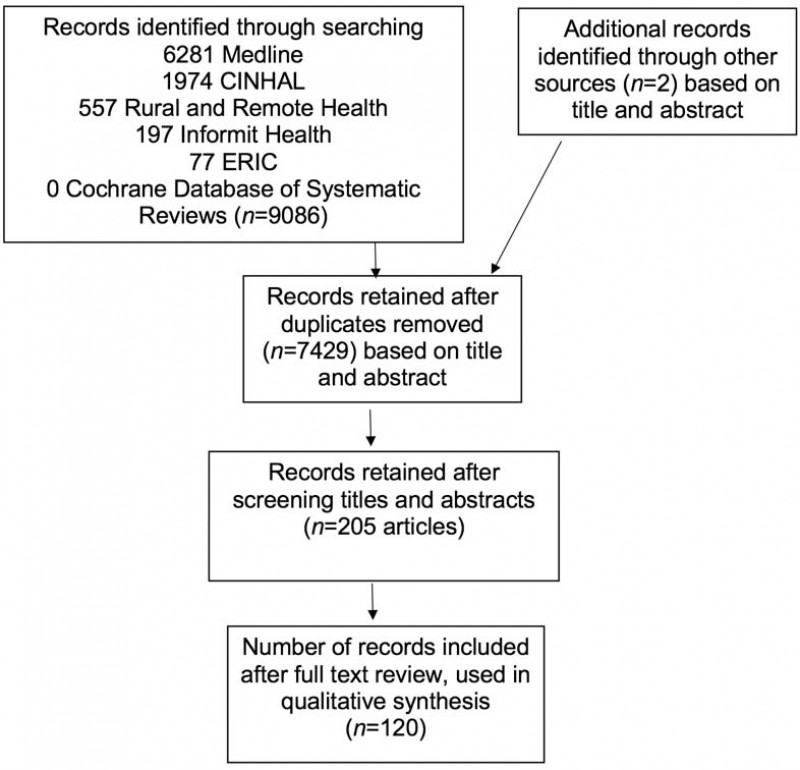

Overall, 9086 articles were identified from databases and 1657 duplicates were removed (Fig1). Abstract and title screening was done for 7429 articles, including two articles identified by key informants (other articles that key informants identified had already been included). Of these, 205 articles were retained after screening titles and abstracts. After full-text review 120 publications met the inclusion criteria: 101 empirical studies and 19 literature reviews (Appendix I). In total, 83 (70%) of the articles included were published in the last 10 years. Of all included literature, most was from Australia (n=97), Canada (n=8), USA (n=2), New Zealand (n=1) and several other high-income countries (n=12).

The main themes of the 120 included articles were workforce and scope of practice (n=9), rural training pathways (n=44), recruitment and retention (n=31), and models of service (n=36).

Figure 1: Prisma flow chart of study selection.

Figure 1: Prisma flow chart of study selection.

Scope of practice

The findings about scope of practice (Appendix II) suggest that at least half of rural allied health professionals work publicly. More privately based groups were optometrists, podiatrists, pharmacists, physiotherapists and psychologists27-30. Rural jobs involved multi-site practice across large catchments, juggling several roles31-36. An extended scope of practice was used to address the diverse community needs, including particular skills in paediatrics, Indigenous health, chronic diseases, health promotion/prevention, primary care and health service management31,33,34,37-41. To manage high service demand within limited staffing and clinical resources, skills in service prioritisation and networking were required33,35,39,42. Assistants were perceived to have the potential to buffer around 17% of allied health workload43. However, these roles were challenging to implement due to issues with professional trust and governance44. In small communities and regions with only intermittent access to allied health providers, training local workers to undertake allied health tasks may improve early and ongoing access, service coordination and culturally safe care31,45-48.

Rural training pathways

The findings about rural training pathways (Appendix III) suggested that 40–66% of rural allied health clinicians had a rural origin and about half had had some rural training experience30,49-51. Accessing allied health university courses was challenging for rural people (limited visibility of the professions, course eligibility, cultural barriers and cost reasons)52,53. Rural training opportunities have expanded in Australia over the past 20 years but generally occur as short placements, restricted to particular disciplines54-56. One univariate study identified that of allied health students who experienced up to 12 months rural training, 50% worked rurally as early career graduates compared with an average for the same disciplines, which was 24%57. Another study that controlled for rural background identified 2–18-week rural placements were associated with 25% of first-year graduates working in rural areas, 42% of whom had rural background. After controlling for rural background, rural placement was significantly associated with rural work, and student perceived quality of placement was an important factor58. The literature identified rural hospital and community settings were potentially suited for allied health curriculum-based learning59,60. UDRHs were described as important organisations for supporting rural clinical training, research and career development61. Upskilling and professional development exemplars included the delivery of advanced paediatric training in a region, rural-specific allied health curriculum, educational modules (online and face-to-face) and professional exchange programs to address specific local service goals62-68.

Recruitment and retention

The recruitment and retention evidence (Appendix IV) suggested that 56% of international physiotherapist graduates would consider working in a rural location69. Tertiary scholarships with rural return of service requirements have the potential to increase the uptake of rural work70. One study quantified the retention in public health services, showing a median turnover of 18 months for dieticians, 3 years for physiotherapists and 4 years for social workers. Reduced turnover was predicted by employment at higher grade (Grade 2 or 3 (highest), compared with Grade 1 (entry level)) or age more than 35 years71. Factors considered important for retention had substantial overlap across the literature and included having a strong local career path (access to senior supervision in the workplace, access to relevant professional development (topic, time and cost)), a supportive practice environment (clearly documented role, orientation to workplace, culturally safe, collegiality, involved in decision-making) and satisfying work (independence in role, variety of work, its community focus and feasible workload)28,29,33,72-78. Various mentorship models may also be of value79. More (84%) private allied health clinicians expressed intention to stay in their rural position for 2 or more years than public allied health clinicians (53%)28.

Models of service

Appendix V summary evidence about models of service suggests that health services prioritise physiotherapy services for regions based on number of public and private allied health professionals available, their skills and community need42. Patient-centred planning and partnerships between different rural public hospitals as well as between public and private providers and in line with other interventions occurring in the community was a way to increase regional access to a more comprehensive range of services80-85. Additionally, clear eligibility criteria, patient referral, shared care and education for staff were considered relevant to increase accessible patient pathways across geographic catchments36,82,86,87. In one review, individual and home-based cardiac rehabilitation (phone and internet) were found to be as effective as hospital-based programs88. Online consultations for allied health were well utilised by doctors, with potential clinical and cost parity with face-to-face services in areas such as diabetic foot healing, rehabilitation and speech pathology89-92. Some providers and clients preferred face-to-face services and considered education services had the highest utility for telehealth90,91,93. Service models delivered by virtual and physical outreach increased access but required strong community engagement and ongoing coordination by trained local workers94,95. Viable business models were considered important for distributing services in small communities32.

Quality of studies

Of the empirical evidence there were only seven national studies, 19 with a whole state or territory focus and 75 based at a community or regional level. Most studies defined allied health but there was no consistency regarding this definition, with important implications for generalisability of the evidence. Empirical studies used a range of methods individually or in combination: 64% surveys, 33% interviews, 12% existing data, 11% focus groups, 4% Delphi process and workshops, 3% environmental scans and 3% descriptive narratives. Most (83%) used cross-sectional designs. Only 8% controlled for confounders and only 14% of studies used control groups.

Across empirical studies, most (55%) had sample sizes greater than 50. The response rate range was 22–100% where reported (mean 46%). Non-response bias was assessed in one study.

Discussion

This review uniquely draws on the most up-to-date published evidence about rural and remote allied health services. By including a diverse range of disciplines and contexts, the findings may provide a more comprehensive backdrop for informing Australia’s priorities and guiding future research than if the review was more restricted. Nineteen other literature reviews were identified but the present study included the largest volume and range of material.

Several policy implications are notable for increasing access to high quality, rural allied health services.

First, the literature describes juggling high demands with a limited number and range of providers. This is a common theme in the broader rural workforce evidence, an issue that increases with remoteness, and has major implications for primary healthcare workforce supply and retention96-98. This suggests that there are not enough of the required allied health disciplines to support rural populations. Rural health workforce planning for this must reorientate away from disciplinary siloes and focus on complementary services, shared roles and broader roles that address the needs of entire rural regions. Jobs growth may also need to occur in a way that covers both hospital (public) sector and private sector roles. Focusing on hospitals alone will limit the potential for building a private sector that has been shown to complement the overall platform of regional service delivery, and underpin growth of particular fields such as optometry, podiatry, pharmacy, physiotherapy and psychology. Notably, the private sector plays a critical role in strengthening primary care and preventative approaches, reducing pressure on hospitals. It is possible that underwriting a critical mass of relevant public and/or private positions in regions and building hubs could help to offset private business and administration costs, which are often high in relation to the income of solo or small practices. Another consideration with respect to growing rural allied health jobs is the development of more senior positions, essential for providing supervision and support to junior staff. The review identified that employing higher grade staff may improve retention and, in turn, create career paths to retain emerging graduates. Plans for growth in rural allied health workforce capacity need to accommodate enough staff to allow time for teaching, outreach, telehealth, professional development and working with a more complex client base across a wide geography.

The second issue is that a more robust rural training and support pathway is urgently needed to achieve a workforce with the right skills and wanting to stay. This pathway needs to support the development of not only a workforce fit for rural hospital work, but also community-based roles, including in primary care, and culturally able to work in Indigenous health. This is similar to the rural generalist pathway in medicine, which aims to develop practitioners with the breadth of skills to practise across hospital and community settings99. The barriers for rural youth accessing allied health university-level training may be harder than in medicine, where rural background quotas are used100. In line with global evidence about rural workforce development, this relies on individual universities embracing rural selection policies, delivering training in rural areas using a rural-facing curriculum to train clinicians adept within a rural practice context and including a range of quality placements (covering preventative, acute and chronic care in hospital and the community, similar to longitudinal integrated clerkships in medicine)101,102. The available evidence suggests that increasing the duration of rural training is urgently needed, specifically targeting the key disciplines that regions need. The evidence in medicine goes further to point out that remoteness and number of rural placements also make a difference to rural work outcomes103. This pathway needs to articulate with graduate positions that have clear orientation processes, regular career check-in and professional development sessions, collegial practice and senior staff supervision. Bundled incentives have been identified as optimal for rural primary care retention as they are adaptable to the wide range of professional and personal factors that have the potential to impact retention in various communities, by rural career and life stages77,98.

Finally, promoting access in more remote locations starts with fostering hubs and engaging in clear business planning for extending clinical service further afield. In thinner, more remote markets, sustainable remuneration packages (or more salaried positions), complementary outreach and telehealth strategies, and networked service models (various hospital clinicians and primary care teams working together) may be fruitful but require policy and coordinated service leadership focused on an overall regional platform beyond any one town. Services operating in remote settings are likely to require more coordination and administrative support, including engaging and supporting geographically dispersed patients to receive early intervention and follow-up care. Ensuring outreach and telehealth services run efficiently is complicated and demands that testing and treatment are primed for clinic clinics on pre-set days. Locally trained personnel need supervision and support to manage patients according to care plans using real-time support when needed. Remote training experiences for allied health students may provide excellent insight into distributed practice models and help to stimulate an allied health workforce that confidently serves more remote populations.

Future research directions

The quality and size of the studies in this review suggest that improved rural allied health research infrastructure (data and research teams) may be required to produce more scalable longitudinal evidence about outcomes. More multivariate studies using controlled designs is warranted for isolating important factors. Priorities for future research include understanding the effects of interventions in education, workforce and service models on access and quality.

Limitations

The review was time-limited, and even though the search was comprehensive (covering 20 years and using six databases), it is possible that some published or in-press material was missed, particularly due to the breadth of disciplines included. This research may not be applicable for informing individual disciplines because allied health was considered at an aggregate level. Most of the evidence was from Australia, which was useful relative to the research objective. However, Australia has different rural and remote health training and service contexts than other high income countries. This, along with the breadth of this review, may mean that care needs to be taken when applying the findings to other countries, specific services, disciplines or rural contexts.

Conclusion

This scoping review of the past 20 years of published rural allied health evidence provides a substantial backdrop for establishing future policy and research priorities for Australia. Findings suggests that although there is a need for more national-scale, longitudinal, outcomes-focused studies, there is a current evidence base to support three key policy areas for more accessible rural allied health services. First, increasing rural allied health public and private sector jobs, coupled with senior workplace supervision and career paths, is needed for retention. Second, training skilled workers through more continuous, high quality rural pathways and across hospital and community settings is likely to support an appropriate workforce for rural communities. Finally, for distribution, critical success depends on regionally based, networked service models incorporating outreach and telehealth, with viable remuneration reinforcing practice in smaller communities.

Acknowledgement

This work was completed using Commonwealth Department of Health resources within the Office of the Rural Health Commissioner.

Declaration of interest

Professor Worley is the National Rural Health Commissioner, an independent statutory officer. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent an official position of the Commonwealth Department of Health or the Australian Government.

references:

appendix I:

Appendix I: Articles used in the review (n=120)Adams J, de Luca K, Swain M, Funabashi M, Wong A, Pagé I, et al. Prevalence and practice characteristics of urban and rural or remote Australian chiropractors: analysis of a nationally representative sample of 1830 chiropractors. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2019;27:34-41.

Adams R, Jones A, Lefmann S, Sheppard L. Decision making about rural physiotherapy service provision varies with sector, size and rurality. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 2015;13(2):1-15.

Adams R, Jones A, Lefmann S, Sheppard L. Rationing is a reality in rural physiotherapy: a qualitative exploration of service level decision-making. BMC Health Services Research. 2015;15:121.

Adams R, Jones A, Lefmann S, Sheppard L. Service level decision-making in rural physiotherapy: development of conceptual models. Physiotherapy Research International. 2016;21(2):116-126.

Adams R, Jones A, Lefmann S, Sheppard L. Towards understanding the availability of physiotherapy services in rural Australia. Rural and Remote Health. 2016;16(2):3686.

Agha A, Liu-Ambrose TYL, Backman CL, Leese J, Li LC. Understanding the experiences of rural community-dwelling older adults in using a new DVD-delivered Otago exercise program: a qualitative study. Interactive Journal of Medical Research. 2015;4(3):e17.

Aoun S, Johnson L. Capacity building in rural mental health in Western Australia. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2002;10(1):39-44.

Bambling M, Kavanagh D, Lewis G, King R, King D, Sturk H, et al. Challenges faced by general practitioners and allied mental health services in providing mental health services in rural Queensland. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2007;15(2):126-130.

Bartik W, Dixon A, Dart K. Aboriginal child and adolescent mental health: a rural worker training model. Australasian Psychiatry. 2007;15(2):135-139.

Battye KM, McTaggart K. Development of a model for sustainable delivery of outreach allied health services to remote north-west Queensland, Australia. Rural and Remote Health. 2003;3(3):194.

Bennett-Levy J, Singer J, DuBois S, Hyde K. Translating e-mental health into practice: what are the barriers and enablers to e-mental health implementation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals? Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(1):e1.

Bent A. Allied health in Central Australia: challenges and rewards in remote area practice. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 1999;45(3):203-212.

Berndt A, Murray CM, Kennedy K, Stanley MJ, Gilbert-Hunt S. Effectiveness of distance learning strategies for continuing professional development (CPD) for rural allied health practitioners: a systematic review. BMC Medical Education. 2017;17(1):117.

Blayden C, Hughes S, Nicol J, Sims S, Hubbard IJ. Using secondments in tertiary health facilities to build paediatric expertise in allied health professionals working in rural New South Wales. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2017;25(6):376-381.

Bond A, Barnett T, Lowe S, Allen P. Retention of allied health professionals in Tasmania. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2013;21(4):236-237.

Boshoff K, Hartshorne S. Profile of occupational therapy practice in rural and remote South Australia. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2008;16(5):255-261.

Bourke L, Waite C, Wright J. Mentoring as a retention strategy to sustain the rural and remote health workforce. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2014;22(1):2-7.

Brockwell D, Wielandt T, Clark M. Four years after graduation: occupational therapists’ work destinations and perceptions of preparedness for practice. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2009;17(2):71-76.

Brown L, Smith T, Wakely L, Wolfgang R, Little A, Burrows J. Longitudinal tracking of workplace outcomes for undergraduate allied health students undertaking placements in rural Australia. Journal of Allied Health. 2017;46(2):79-87.

Campbell A. The evaluation of a model of primary mental health care in rural Tasmania. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2005;13(3):142-148.

Campbell N, McAllister L, Eley D. The influence of motivation in recruitment and retention of rural and remote allied health professionals: a literature review. Rural and Remote Health. 2012;12(3):1900.

Chang AB, Grimwood K, Maguire G, King PT, Morris PS, Torzillo PJ. Management of bronchiectasis and chronic suppurative lung disease in indigenous children and adults from rural and remote Australian communities. Medical Journal of Australia. 2008;189(7):386-393.

Charles G, Bainbridge L, Copeman-Stewart K, Kassam R, Tiffin S. Impact of an interprofessional rural health care practice education experience on students and communities. Journal of Allied Health. 2008;37(3):127-131.

Chisholm M, Russell D, Humphreys J. Measuring rural allied health workforce turnover and retention: what are the patterns, determinants and costs? Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2011;19(2):81-88.

Clark RA, Conway A, Poulsen V, Keech W, Tirimacco R, Tideman P. Alternative models of cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2015;22(1):35-74.

Cohn RJ, Goodenough B. Health professionals’ attitudes to videoconferencing in paediatric health-care. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2002;8(5):274-282.

Colles SL, Belton S, Brimblecombe J. Insights into nutritionists’ practices and experiences in remote Australian Aboriginal communities. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2016;40:S7-S13.

Cosgrave C, Malatzky C, Gillespie J. Social determinants of rural health workforce retention: a scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(3):314.

Cosgrave C, Maple M, Hussain R. An explanation of turnover intention among early-career nursing and allied health professionals working in rural and remote Australia – findings from a grounded theory study. Rural and Remote Health. 2018;18(3):4511.

Cox R, Hurwood A. Queensland Health trial of an allied health postgraduate qualification in remote health practice. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2005;13(3):191-192.

Devine SG, Williams G, Nielsen I. Rural allied health scholarships: do they make a difference? Rural and Remote Health. 2013;13(4):2459.

Dew A, Bulkeley K, Veitch C, Bundy A, Gallego G, Lincoln M, et al. Addressing the barriers to accessing therapy services in rural and remote areas. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2013;35(18):1564-1570.

Doherty G, Stagnitti K, Schoo AMM. From student to therapist: follow up of a first cohort of Bachelor of Occupational Therapy students. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2009;56(5):341-349.

Dow B, Moore K, Dunbar JM, Nankervis J, Hunt S. A description and evaluation of an innovative rural rehabilitation programme in South Eastern Australia. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010;32(9):781-789.

D’Souza R. A pilot study of an educational service for rural mental health practitioners in South Australia using telemedicine. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2000;6(Suppl1):S187-S189.

Ducat WH, Burge V, Kumar S. Barriers to, and enablers of, participation in the Allied Health Rural and Remote Training and Support (AHRRTS) program for rural and remote allied health workers: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Medical Education. 2014;14:194.

Ducat WH, Kumar S. A systematic review of professional supervision experiences and effects for allied health practitioners working in non-metropolitan health care settings. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2015;8:397-407.

Durey A, Haigh M, Katzenellenbogen JM. What role can the rural pipeline play in the recruitment and retention of rural allied health professionals? Rural and Remote Health. 2015;15(3):3438.

Durey A, McNamara B, Larson A. Towards a health career for rural and remote students: cultural and structural barriers influencing choices. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2003;11(3):145-150.

Durkin SR. Eye health programs within remote Aboriginal communities in Australia: a review of the literature. Australian Health Review. 2008;32(4):664-676.

Fahey A, Day NA, Gelber H. Tele-education in child mental health for rural allied health workers. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2003;9(2):84-88.

Fairweather GC, Lincoln MA, Ramsden R. Speech-language pathology telehealth in rural and remote schools: the experience of school executive and therapy assistants. Rural and Remote Health. 2017;17(3):1-13.

Field PE, Franklin RC, Barker RN, Ring I, Leggat PA. Cardiac rehabilitation services for people in rural and remote areas: an integrative literature review. Rural and Remote Health. 2018;18(4):1-13.

Fisher KA, Fraser JD. Rural health career pathways: research themes in recruitment and retention. Australian Health Review. 2010;34(3):292-296.

Foo J, Storr M, Maloney S. The characteristics and experiences of international physiotherapy graduates seeking registration to practise in Australia. New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy. 2017;45(3):135-142.

Fragar LJ, Depczynski JC. Beyond 50. Challenges at work for older nurses and allied health workers in rural Australia: a thematic analysis of focus group discussions. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11:42.

Greenstein C, Lowell A, Thomas DP. Improving physiotherapy services to Indigenous children with physical disability: are client perspectives missed in the continuous quality improvement approach? Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2016;24(3):176-181.

Guilfoyle C, Wootton R, Hassall S, Offer J, Warren M, Smith D. Preliminary experience of allied health assessments delivered face to face and by videoconference to a residential facility for elderly people. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2003;9(4):230-233.

Hassall S, Wootton R, Guilfoyle C. The cost of allied health assessments delivered by videoconference to a residential facility for elderly people. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2003;9(4):234-237.

Hill AJ, Miller LE. A survey of the clinical use of telehealth in speech-language pathology across Australia. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology. 2012;14(3):110-117.

Hill ME, Raftis D, Wakewich P. Strengthening the rural dietetics workforce: examining early effects of the Northern Ontario Dietetic Internship Program on recruitment and retention. Rural and Remote Health. 2017;17(1):4035.

Hoffmann T, Cantoni N. Occupational therapy services for adult neurological clients in Queensland and therapists’ use of telehealth to provide services. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2008;55(4):239-248.

Iacono T, Stagg K, Pearce N, Hulme Chambers A. A scoping review of Australian allied health research in ehealth. BMC Health Services Research. 2016;16(1):543.

Johnston C, Newstead C, Sanderson M, Wakely L, Osmotherly P. The changing landscape of physiotherapy student clinical placements: an exploration of geographical distribution and student performance across settings. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2017;25(2):85-93.

Keane S, Lincoln M, Rolfe M, Smith T. Retention of the rural allied health workforce in New South Wales: a comparison of public and private practitioners. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:32.

Keane S, Lincoln M, Smith T. Retention of allied health professionals in rural New South Wales: a thematic analysis of focus group discussions. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:175.

Keane S, Smith T, Lincoln M, Fisher K. Survey of the rural allied health workforce in New South Wales to inform recruitment and retention. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2011;19(1):38-44.

Kingston GA, Williams G, Judd J, Gray MA. Hand therapy services for rural and remote residents: results of a survey of Australian occupational therapists and physiotherapists. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2015;23(2):112-121.

Kuipers P, Hurwood A, McBride LJ. Audit of allied health assistant roles: suggestions for improving quality in rural settings. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2015;23(3):185-188.

Kumar S, Osborne K, Lehmann T. Clinical supervision of allied health professionals in country South Australia: a mixed methods pilot study. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2015;23(5):265-271.

Lai GC, Taylor EV, Haigh MM, Thompson SC. Factors affecting the retention of Indigenous Australians in the health workforce: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(5): 914.

Laurence C, Wilkinson D. Towards more rural nursing and allied health services: current and potential rural activity in the Division of Health Sciences of the University of South Australia. Rural and Remote Health. 2002;2(1):105.

Leys J, Wakely L, Thurlow K, Hyde Page R. Physiotherapy students in rural emergency departments: a NEAT place to learn. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2017;25(2):130-131.

Lin IB, Beattie N, Spitz S, Ellis A. Developing competencies for remote and rural senior allied health professionals in Western Australia. Rural and Remote Health. 2009;9(2):1115.

Mackenzie L, O’Toole G. Profile of 1 year of fieldwork experiences for undergraduate occupational therapy students from a large regional Australian university. Australian Health Review. 2017;41(5):582-589.

Maloney P, Stagnitti K, Schoo A. Barriers and enablers to clinical fieldwork education in rural public and private allied health practice. Higher Education Research and Development. 2013;32(3):420-435.

Manahan CM, Hardy CL, MacLeod MLP. Personal characteristics and experiences of long-term allied health professionals in rural and northern British Columbia. Rural and Remote Health. 2009;9(4):1238.

Mathu-Muju KR, McLeod J, Walker ML, Chartier M, Harrison RL. The Children’s Oral Health Initiative: an intervention to address the challenges of dental caries in early childhood in Canada's First Nation and Inuit communities. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2016;107(2):e188-e193.

McAuliffe T, Barnett F. Factors influencing occupational therapy students’ perceptions of rural and remote practice. Rural and Remote Health. 2009;9(1):1078.

McKellips F, Keely E, Afkham A, Liddy C. Improving access to allied health professionals through the Champlain BASE™ eConsult service: a cross-sectional study in Canada. British Journal of General Practice. 2017;67(664):e757-e763.

McLeod S, Barbara A. Online technology in rural health: supporting students to overcome the tyranny of distance. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2005;13(5):276-281.

Merritt J, Perkins D, Boreland F. Regional and remote occupational therapy: a preliminary exploration of private occupational therapy practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2013;60(4):276-287.

Nagel T, Robinson G, Condon J, Trauer T. Approach to treatment of mental illness and substance dependence in remote Indigenous communities: results of a mixed methods study. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2009;17(4):174-182.

Nancarrow SA, Young G, O’Callaghan K, Jenkins M, Philip K, Barlow K. Shape of allied health: an environmental scan of 27 allied health professions in Victoria. Australian Health Review. 2017;41(3):327-335.

Newman CS, Cornwell PL, Young AM, Ward EC, McErlain AL. Accuracy and confidence of allied health assistants administering the subjective global assessment on inpatients in a rural setting: a preliminary feasibility study. Nutrition and Dietetics. 2018;75(1):129-136.

O’Brien M, Phillips B, Hubbard W. Enhancing the quality of undergraduate allied health clinical education: a multidisciplinary approach in a regional/rural health service. Focus on Health Professional Education. 2010(1):11-22.

O’Hara R, Jackson S. Integrating telehealth services into a remote allied health service: a pilot study. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2017;25(1):53-57.

O’Toole K, Schoo A, Hernan A. Why did they leave and what can they tell us? Allied health professionals leaving rural settings. Australian Health Review. 2010;34(1):66-72.

O’Toole K, Schoo A, Stagnitti K, Cuss K. Rethinking policies for the retention of allied health professionals in rural areas: a social relations approach. Health Policy 2008;87(3):326-332.

O’Toole K, Schoo AM. Retention policies for allied health professionals in rural areas: a survey of private practitioners. Rural and Remote Health. 2010;10(2):1331.

Pacza T, Steele L, Tennant M. Development of oral health training for rural and remote Aboriginal health workers. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2001;9(3):105-110.

Parkin AE, McMahon S, Upfield N, Copley J, Hollands K. Work experience program at a metropolitan paediatric hospital: assisting rural and metropolitan allied health professionals exchange clinical skills. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2001;9(6):297-303.

Playford D, Larson A, Wheatland B. Going country: rural student placement factors associated with future rural employment in nursing and allied health. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2006;14(1):14-19.

Prout S, Lin I, Nattabi B, Green C. ‘I could never have learned this in a lecture’: transformative learning in rural health education. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice. 2014;19(2):147-159.

Richardson I, Slifkin R, Randolph R, Holmes GM. A rural-urban comparison of allied health professionals’ average hourly wage. Journal of Allied Health. 2010;39(3):e91-e96.

Roots RK, Brown H, Bainbridge L, Li LC. Rural rehabilitation practice: perspectives of occupational therapists and physical therapists in British Columbia, Canada. Rural and Remote Health. 2014;14(1):2506.

Roots RK, Li LC. Recruitment and retention of occupational therapists and physiotherapists in rural regions: a meta-synthesis. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:59.

Russell D, McGrail M, Humphreys J. Determinants of rural Australian primary health care worker retention: a synthesis of key evidence and implications for policymaking. Australian Journal of Rural Health 2017;25:5-14.

Sartore GM, Kelly B, Stain HJ, Fuller J, Fragar L, Tonna A. Improving mental health capacity in rural communities: mental health first aid delivery in drought-affected rural New South Wales. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2008;16(5):313-318.

Schmidt D, Kurtz M, Davidson S. Creating rural allied health leadership structures using district advisors: an action research project using program logic. Journal of Allied Health. 2017;46(3):185-191.

Smith JD, O’Dea K, McDermott R, Schmidt B, Connors C. Educating to improve population health outcomes in chronic disease: an innovative workforce initiative across remote, rural and Indigenous communities in northern Australia. Rural and Remote Health. 2006;6(3):606.

Smith T, Brown L, Cooper R. A multidisciplinary model of rural allied health clinical-academic practice: a case study. Journal of Allied Health. 2009;38(4):236-241.

Smith T, Cooper R, Brown L, Hemmings R, Greaves J. Profile of the rural allied health workforce in northern New South Wales and comparison with previous studies. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2008;16(3):156-163.

Smith T, Cross M, Waller S, Chambers H, Farthing A, Barraclough F, et al. Ruralization of students’ horizons: insights into Australian health professional students’ rural and remote placements. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2018;11:85-97.

Smith T, Fisher K, Keane S, Lincoln M. Comparison of the results of two rural allied health workforce surveys in the Hunter New England region of New South Wales: 2005 versus 2008. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2011;19(3):154-159.

Somerville L, Davis A, Elliott AL, Terrill D, Austin N, Philip K. Building allied health workforce capacity: a strategic approach to workforce innovation. Australian Health Review. 2015;39(3):264-270.

Speyer R, Denman D, Wilkes-Gillan S, Chen YW, Bogaardt H, Kim JH, et al. Effects of telehealth by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2018;50(3):225-235.

Spiers M, Harris M. Challenges to student transition in allied health undergraduate education in the Australian rural and remote context: a synthesis of barriers and enablers. Rural and Remote Health. 2015;15(2):3069.

Stagnitti K, Schoo A, Dunbar J, Reid C. An exploration of issues of management and intention to stay: allied health professionals in South West Victoria, Australia. Journal of Allied Health. 2006;35(4):226-232.

Stagnitti K, Schoo A, Reid C, Dunbar J. Access and attitude of rural allied health professionals to CPD and training. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2005;12(8):355-362.

Stagnitti K, Schoo A, Reid C, Dunbar J. Retention of allied health professionals in the south-west of Victoria. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2005;13(6):364-365.

Stuart J, Hoang H, Crocombe L, Barnett T. Relationships between dental personnel and non-dental primary health care providers in rural and remote Queensland, Australia: dental perspectives. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):99.

Stute M, Hurwood A, Hulcombe J, Kuipers P. Pilot implementation of allied health assistant roles within publicly funded health services in Queensland, Australia: results of a workplace audit. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:258.

Sutton K, Maybery D, Moore T. Bringing them home: a Gippsland mental health workforce recruitment strategy. Australian Health Review. 2012;36(1):79-82.

Sutton KP, Maybery D, Patrick KJ. The longer term impact of a novel rural mental health recruitment strategy: a quasi-experimental study. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2015;7(4):391-397.

Sutton KP, Patrick K, Maybery D, Eaton K. Increasing interest in rural mental health work: the impact of a short term program to orientate allied health and nursing students to employment and career opportunities in a rural setting. Rural and Remote Health. 2015;15(4):3344.

Tan ACW, Emmerton L, Hattingh HL. A review of the medication pathway in rural Queensland, Australia. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2012;20(5):324-339.

Tan ACW, Emmerton LM, Hattingh HL. Issues with medication supply and management in a rural community in Queensland. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2012;20(3):138-143.

Taylor J, Carlisle K, Farmer J, Larkins S, Dickson-Swift V, Kenny A. Implementation of oral health initiatives by Australian rural communities: factors for success. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2018;26(1):e102-e110.

Thomas Y, Clark M. The aptitudes of allied health professionals working in remote communities. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2007;14(5):216-220.

Thomasz T, Young D. Speech pathology and occupational therapy students participating in placements where their supervisor works in a dual role. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2016;24(1):36-40.

Walker D, Tennant M, Short SD. An exploration of the priority remote health personnel give to the development of the Indigenous Health Worker oral health role and why: unexpected findings. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2013;21(5):274-278.

Watanabe-Galloway S, Madison L, Watkins KL, Nguyen AT, Chen LW. Recruitment and retention of mental health care providers in rural Nebraska: perceptions of providers and administrators. Rural and Remote Health. 2015;15(4):3392.

Watson J, Gasser L, Blignault I, Collins R. Taking telehealth to the bush: lessons from north Queensland. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2001;7(Suppl2):20-23.

Whitford D, Smith T, Newbury J. The South Australian Allied Health Workforce survey: helping to fill the evidence gap in primary health workforce planning. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2012;18(3):234-241.

Wielandt PM, Taylor E. Understanding rural practice: implications for occupational therapy education in Canada. Rural and Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1488.

Willems J, Sutton K, Maybery D. Using a Delphi process to extend a rural mental health workforce recruitment initiative. Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice. 2015;10(2):91-100.

Williams E, D’Amore W, McMeeken J. Physiotherapy in rural and regional Australia. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2007;15(6):380-386.

Williams EN, McMeeken JM. Building capacity in the rural physiotherapy workforce: a paediatric training partnership. Rural and Remote Health. 2014;14(1):2475.

Winn CS, Chisholm BA, Hummelbrunner JA. Factors affecting recruitment and retention of rehabilitation professionals in Northern Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. Rural and Remote Health. 2014;14(2):2619.

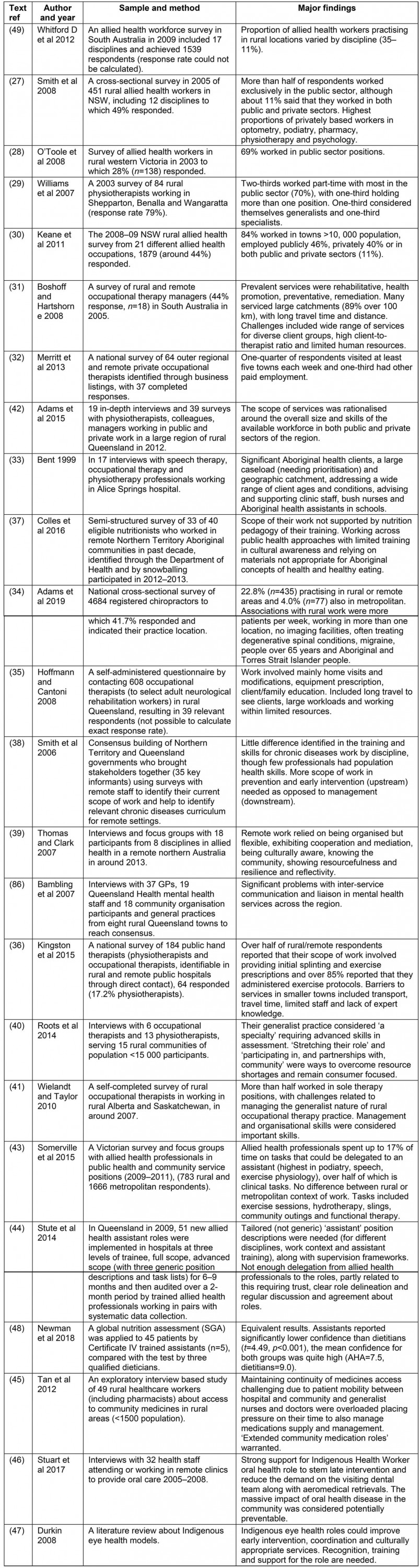

appendix II:

Appendix II: Key findings about workforce and scope of practice

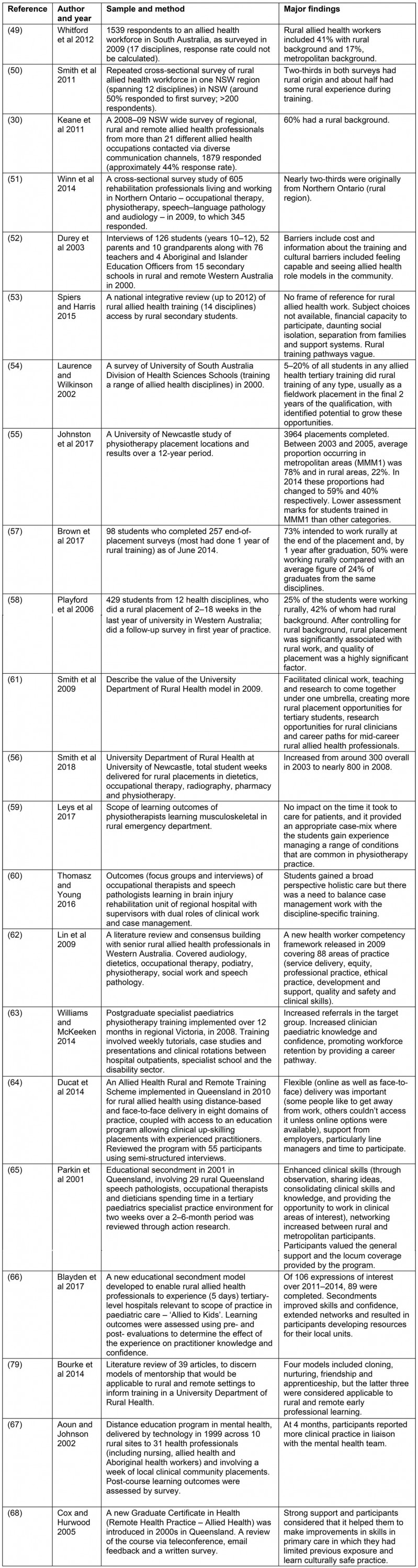

appendix III:

Appendix III: Key findings about rural training pathways

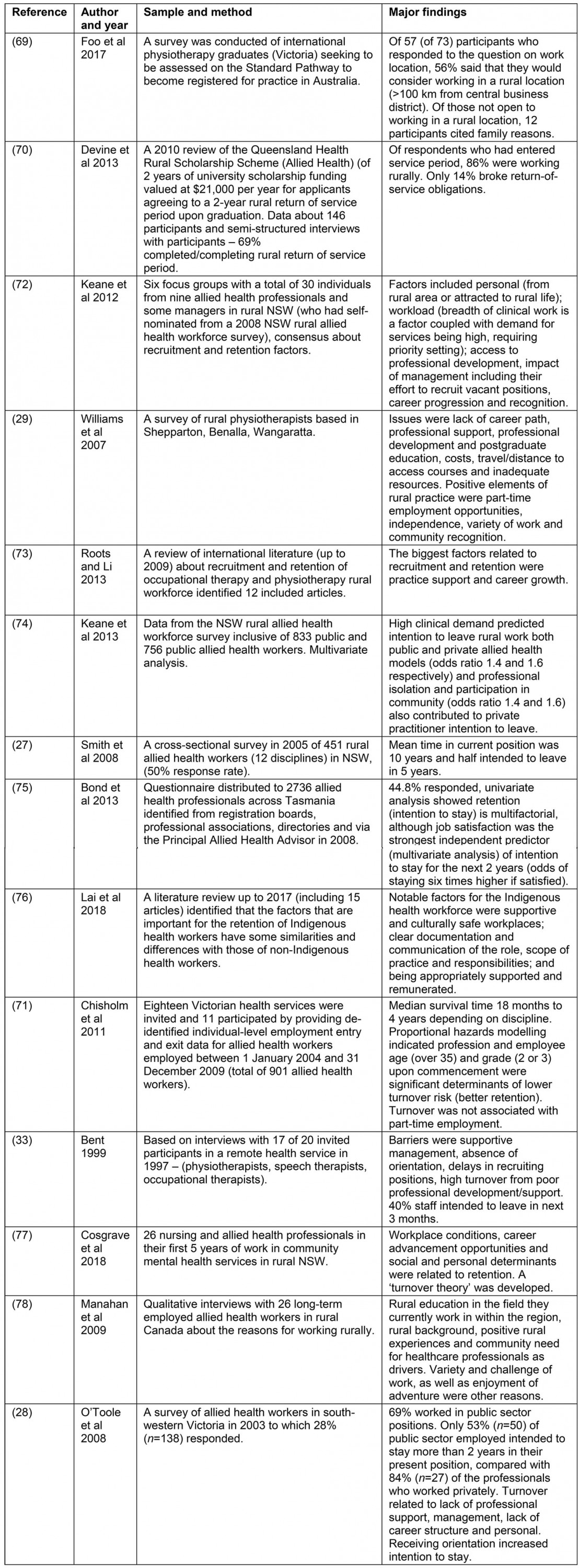

appendix IV:

Appendix IV: Key findings about recruitment and retention

appendix V:

Appendix V: Key findings about models of service